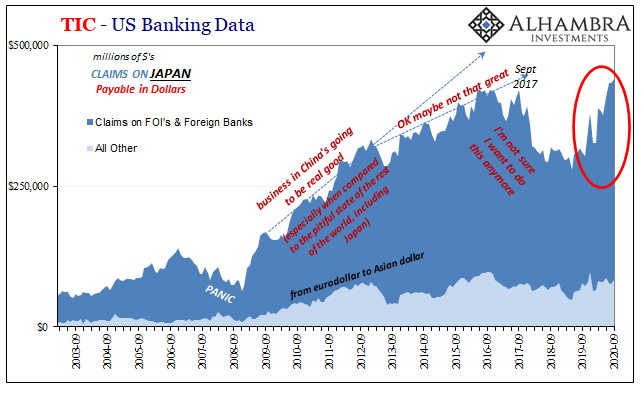

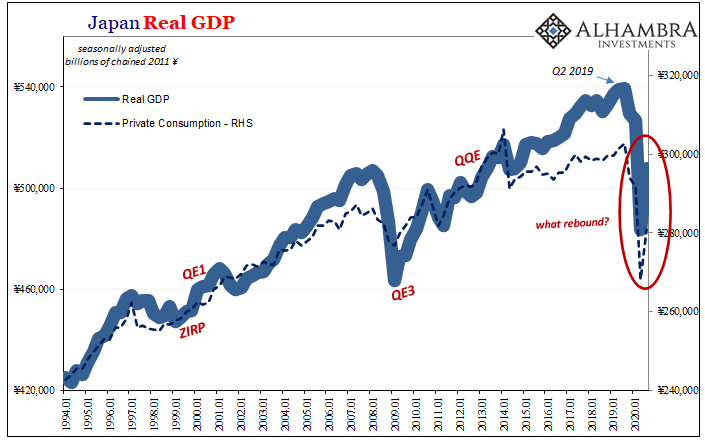

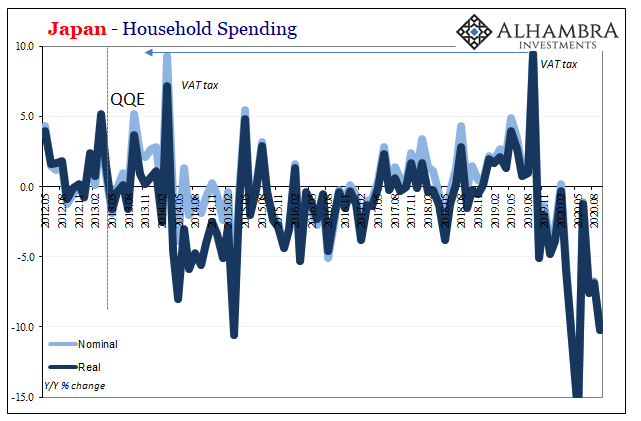

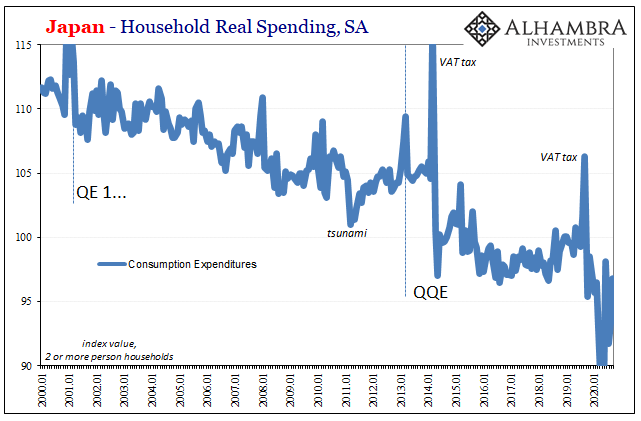

Speaking of Japan, it’s not difficult to figure out why Japanese banks might seek some small pittance from diving back in the choppy waters of eurodollar redistribution. Conditions at home, particularly since the middle of last year (right when the big turn Tokyo dollars came up), have been, to put it mildly, way less than ideal. Politicians listening to central bankers, as they always do, as they all do, were fooled into believing the Japanese economy had only temporarily stumbled in 2018, and with the marvelous assistance of those central bankers had made its way into recovery, or close enough to one, for the twice-delayed VAT tax hike to take effect.

Instead, Japan’s economy peaked during last year’s second quarter and was already partway into (another) recession by the time former PM Abe’s government blundered into its fiscal adjustment. In truth, the Japanese suffered a mild recession in 2018 and the economy was on track to be hit with a double-dip before midyear last year, hardly a system on solid ground for such a tax jolt.

The Bank of Japan, as per usual, decided to keep up and accelerate the creation of useless bank reserves – useless at least in the respect of Japanese banks doing something in response to them in Japan.

Theoretically, QE, or QQE, is supposed to work through either signaling or portfolio rebalancing. Studies have shown time and again it doesn’t work through either.

However, with regard to portfolio rebalancing, that’s not completely true as a technical matter when it comes to the full range of monetary possibilities globally. Bank reserves haven’t provoked bank lending or domestic financial expansion in the manner of a real recovery, that much has been absolutely true, but they do serve a narrower external purpose.

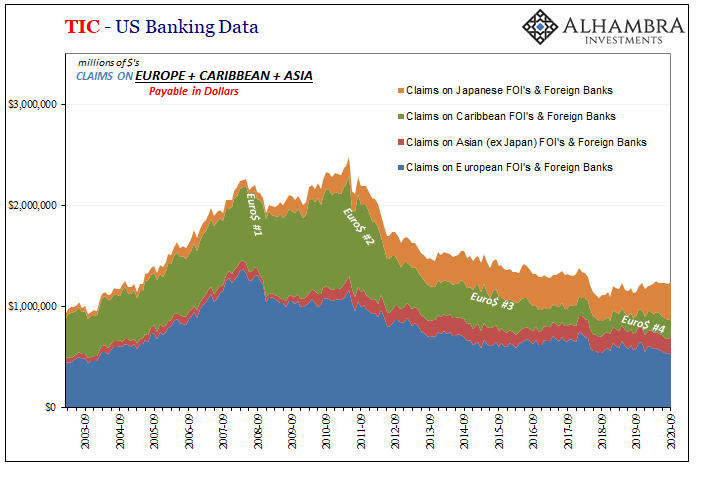

A Japanese bank flush with reserves on account with the Bank of Japan can use them as collateral in a currency swap (or basis swap), thereby acquiring “dollars” from largely American banks at relatively cheaper costs (collateralized). The reason why is that those reserves can be converted, at a moment’s notice, into JGB’s held at the BoJ or, on an expanded 2016 program, right into US Treasury securities already in official Japanese custody.

Of course, none of this is what the BoJ has had in mind when designing and then executing QQE, creating so many reserves as the necessary accounting byproduct. Defeating the purpose, in some ways, they’ve allowed Japanese banks to do more things outside of Japan at certain times; or, at least, indirectly subsidizing the process.

Especially the last year or so:

Again, why Japanese banks would act this way is very easy to see. There’s risk and heavy costs in the global dollar shortage, but there are more in a domestic economy that can never get out of its own way. Globally synchronized downturn turning Japan toward a harmful double dip, with the government convinced otherwise and piling on more harm,

no wonder Japan’s financial institutions might seek some meager opportunities elsewhere using yen bank reserves as the backstop.

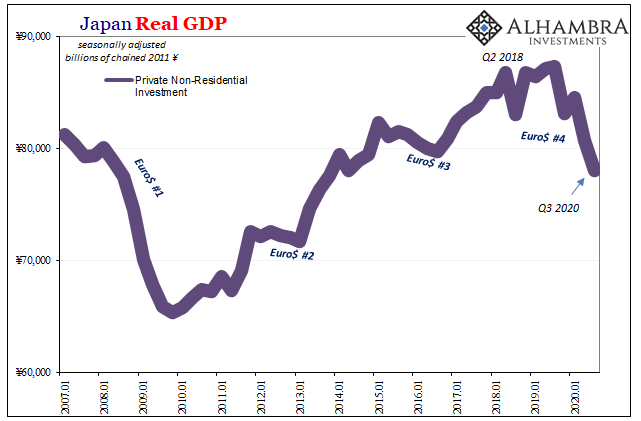

It hasn’t changed any in the wake of COVID. In fact, Japan’s rebound from the second quarter trough has been arguably the worst of any major economy. Though the headline growth rate was the usual gigantic (+21% annual rate, Q/Q), and it seemed relatively complete when compared to the huge quarterly decline preceding it (-29% annual rate), in reality the rebound was nothing like one:

As usual, it is Japanese consumers (workers) who bear the brunt of this disaster of an economy. Private consumption in Q3, not Q2, was about the same as it had been at the worst point of Japan’s Great “Recession” experience in 2009. Yep, consumer spending had to rebound and only that much in order to equal the lowest point of that big prior trough.

QQE, as you can see above, never fixed Japan’s moribund growth paradigm but it did manage to make it worse for private consumption (therefore, the Japanese people).

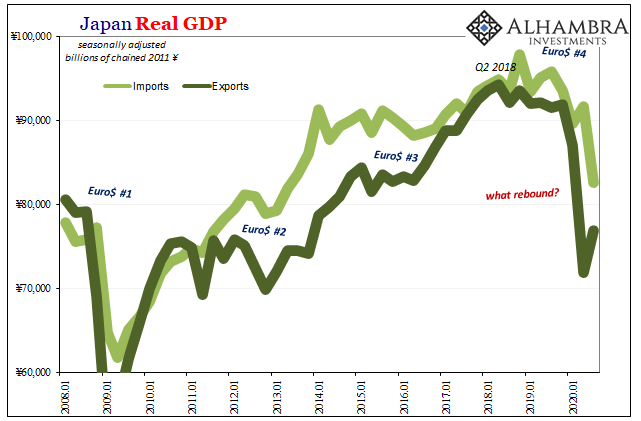

Elsewhere in GDP figures released to start this week, much the same theme. Japan’s exports barely rose (alarmingly weak, because global trade has been at the forefront of whichever way the global economy has turned over the past dozen years; if global trade is struggling, barely moving up let alone anything like recovery, no shock there’s been a summer slowdown!) while imports continued to fall, an acknowledgement of just how little demand there is particularly from households.

Perhaps the most concerning part of Japan’s economy has to do with fixed investment. The decline in productive spending actually accelerated in the third quarter, in some part surely echoing what Japanese banks are doing financing only slightly better rebounds in places far, far from Japan’s shores.

Private Non-residential Investment was as low as it had been in 2013, which was barely as much as it had been back in early 2008. Suffering, by far, the largest setback – again, in Q3! – since 2009, Japan’s financial factors line up facing outside. Marginal investment in Japan is non-existent.

But, like the rest of the eurodollar system reducing its exposure, though Japan’s banks may find relative opportunity elsewhere, that only means slightly better than the maybe the worst of the sorriest bunch. Japan, like Germany, has been a bellwether particularly since Euro$ #4 showed up once, ironically, Japanese banks began the stampede out of it.

With the rest of the world still in eurodollar retreat, and Japan’s economy struggling so much that Tokyo Inc. seeks some modest use for yen reserves elsewhere, does that bellwether status still apply?

The world hopes that it doesn’t. The grass may look greener from Tokyo, like it had in 2017, but the rest of the banking world appears to still be betting that it does.

Stay In Touch