With government cash being shoveled into personal and corporate bank accounts, US consumers have reported that they are being more optimistic about the state of the economy. Before that, they went on a spending binge as stated unequivocally by historic retail sales figures. Why, then, so much higher spending than improved happiness and certainty while going about it?

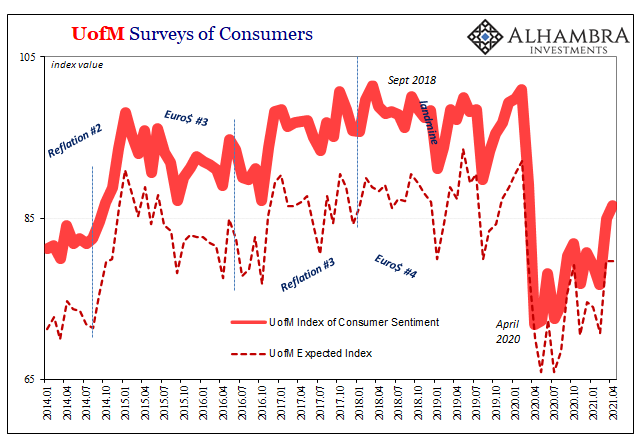

The University of Michigan’s consumer survey index increased to 86.5 for the month of April 2021, up from 84.9 (revised) during March. Last month’s estimate had shown the bigger jump with the arrival of Uncle Sam’s check writing; just 76.8 in the winter freeze of February.

While up from the cold, hardly in the same territory as the scorch of retailer registers barely able to keep up printing consumer receipts. The expectations component of the Michigander catalog was flat March to April, and isn’t even as much off last year’s bottom as the headline.

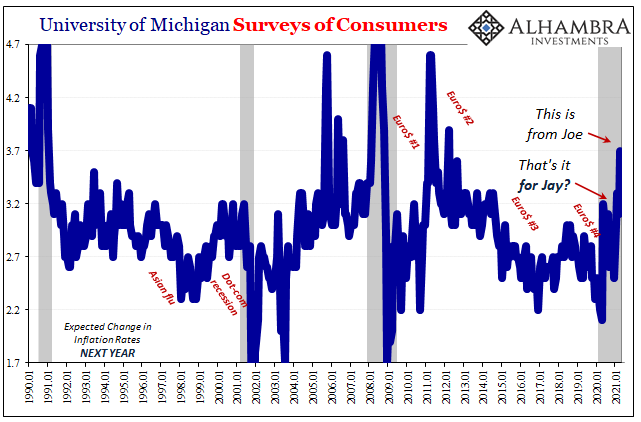

But none of this is actually the headline for entire set of data which the UofM has helpfully pieced together nearly half a century. The “a ha” in it, if you will, was the inflation expectations series. According to their latest survey panels of likely shoppers, these government-fueled spendthrifts (altogether on average) now in April believe that one year from today the inflation rate is likely to be somewhere around 3.7%.

That’s not just up from 3.1% as stated during March, it’s the highest expected short run inflation going back to 2012. Like the PPI, another decade high in some part of the overall price equation. And according to Economists, expectations should be a big part.

Gasoline prices play a key role in consumer expectations, of course, as would the base effects of being compared to gasoline and oil prices having plunged in the year earlier period. After all, that’s why you see 2011 to early 2012 one-year inflation expectations shown above at similar rates to 2021.

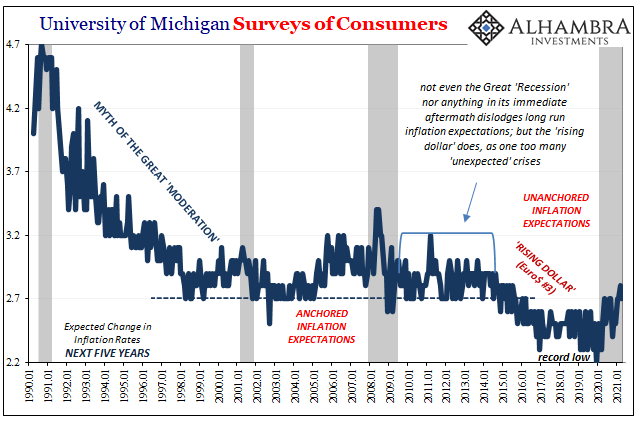

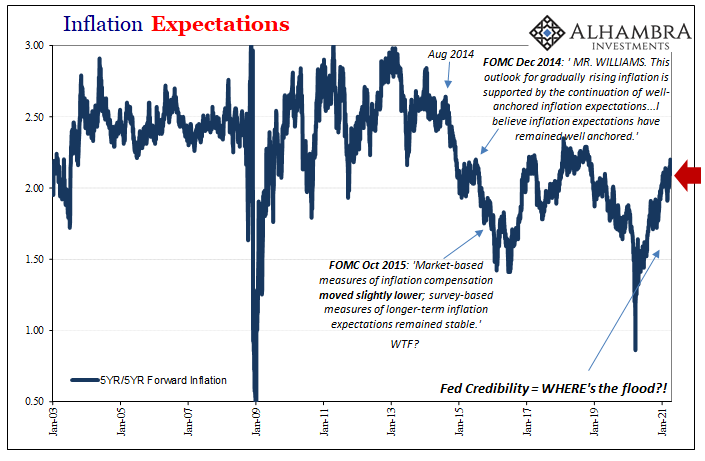

Unlike ten years ago, however, back then consumers apparently felt it would stick around for a while – as in, actual (sustained) inflation. Even when Ben Bernanke told them it probably wouldn’t beyond the interim, the 5-year forward inflation outlook, according to the Michigan survey, was still anchored around the same as the pre-crisis period. Both consumers and Bernanke apparently felt it would happen if given enough time.

It’s appreciably lower now despite the big pickup in the shorter run, down in April, actually, from March.

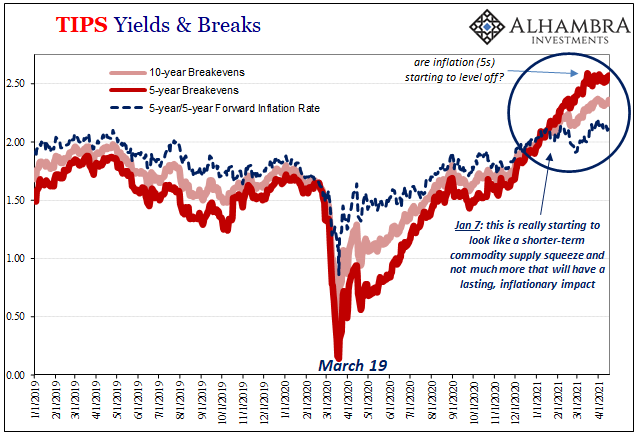

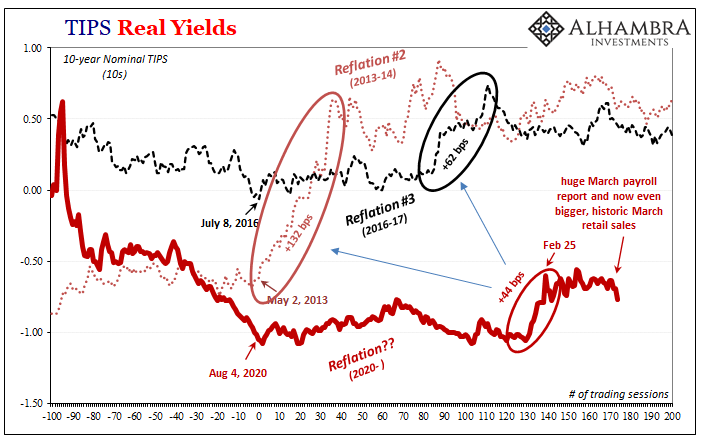

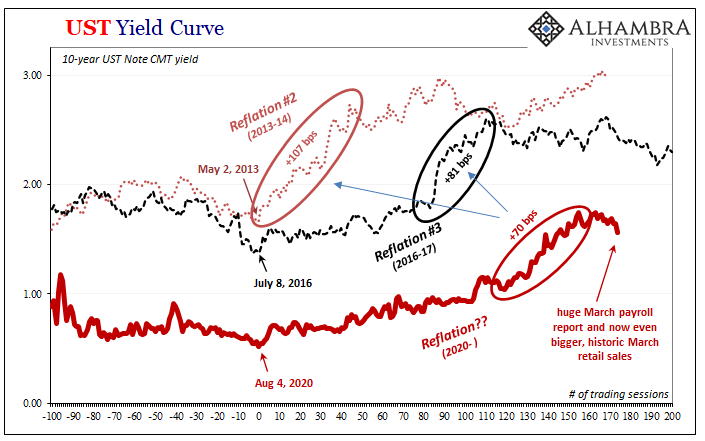

This is remarkably the same inflation picture as has been priced into the TIPS market this year, too. As previously noted, this other market-based term-structure of inflation expectations had inverted (below) going back to early January when short-run inflation breakevens (5s and in) surged in tandem with oil and gasoline.

Even as commodities influenced those calculations, however, longer-run inflation estimates remained subdued, and are still right now; like the UofM, these had improved from 2020, but do not represent some significant change or even a 10-year high like short-term indications.

Both consumers and the investment consumers of TIPS instruments seem to agree – with Jay Powell, no less – that inflation probabilities are meaningfully higher only in the short run because they’ve been influenced by, as Powell and Bernanke both put it, “transitory” factors such as base effects and commodity price rebounds.

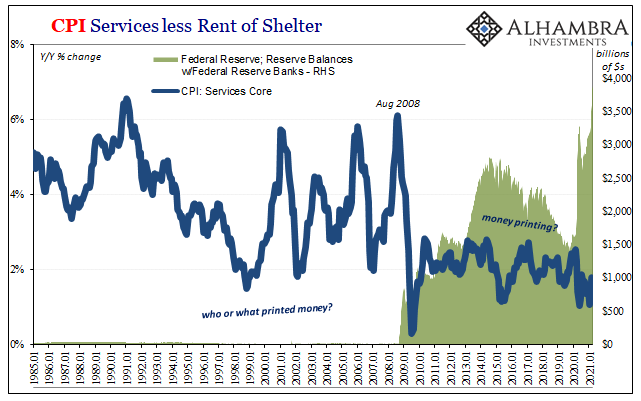

This actually isn’t inflation, according to the useful definition of it, derived as it is from the non-transitory achievement of monetary flow as well as how that flow influences total macro factors including the elimination of any macro slack leftover.

Those aren’t nearly enough to suggest anything more than a plain economic rebound from a serious low, as had been the case, obviously, in 2011 and 2012 following 2009 and 2010.

So, again, where is the consensus for looming inflationary liftoff? Only in the media. Not even flush consumers are thinking anything beyond the immediacy of early 2021. Like the vastly more sizable and sophisticated bond market, neither expects much to last.

Common sense laypeople and complex financials, each coming to the same conclusion at around the same time. Pretty remarkable especially considering what each has to deal with so far as mainstream influences uniformly relaying only inflation certainty.

It may not seem like it, but the deflation case – not inflation – remains the consensus. Not in the media, of course, which presents a uniform view. But the whole damn bond market globally is resolute, and that's so bigger and more powerful.@MacroVoices https://t.co/qMnhOSv6sR pic.twitter.com/FUVOoDFd8K

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) April 16, 2021

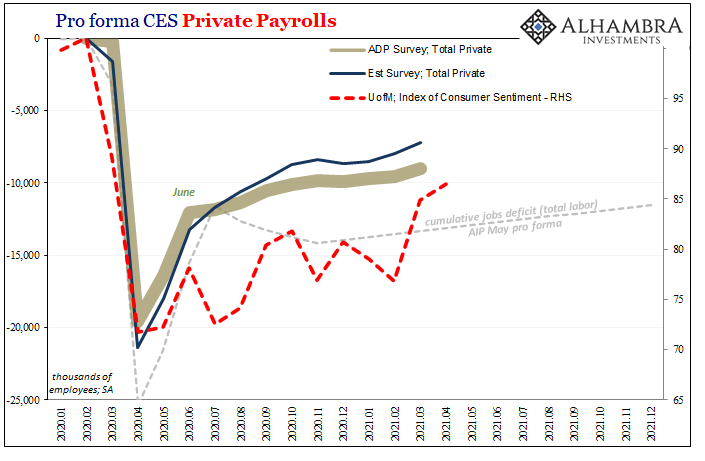

The US and global economy is absolutely still improving, but what does that actually mean? For now, it’s much better than the alternative. For what comes next, as 2011-12, rebound isn’t nearly enough (see: China) to get all the way there. What had happened in 2011 was Euro$ #2. Will the world be able to avoid a repeat this time, a Euro$ #5?

Neither bonds (esp. since Feb 25) nor consumers appear to be expecting it.

Stay In Touch