When Alan Greenspan sat in front of the politicians in Congress back in February 2005, he purposefully made it seem like what was taking place at that time was some kind of new and unusual development. Yeah, the guy who had previously become famous for fedspeak – the ability to use a lot of words while saying nothing – would regularly slip right out of it whenever it suited his purposes.

Those were inflation, back in early ’05. Already people were growing nervous, something about house prices and how these were being financed. The Fed’s job, as those at the “central bank” saw it, was to influence behavior so that neither the economy nor the financial system moved too far in either direction – inflation or deflation.

Keep everything right down the middle, as seemed to have suited everyone in the Great “Moderation” of the nineties.

But how does this work, specifically? And how do we tell if it is, or is not, working?

What the “maestro” didn’t say in Congress was anything at all about the monetary system. Inflation or deflation, both were and will always remain monetary diseases yet in what would end up being some of his most memorable testimony Alan Greenspan never said the word “money” once; not a single mention in his prepared remarks.

He did manage to say “inflation” fourteen times, however.

The relevant background: the dot-com recession of 2001 had been especially mild yet the “jobless recovery” from it nearly cost George W. Bush his 2004 reelection. Policymakers at the Fed already perplexed by this went to “extraordinary” lengths cutting their fed funds target all the way down to one percent in June 2003 – almost two years after the recession had ended.

One year later, June 2004, the economy picked up, the labor market accelerated and Bush was soon back in the White House.

With the fed funds target still at 1%, Greenspan and his staff of Economists began to consider whether or not they’d done too much; worried they had erred too far on the side of dot-com bust and deflation (which was never a real risk).

So, the doves turned hawks and rate hikes started up and continued one after another after another.

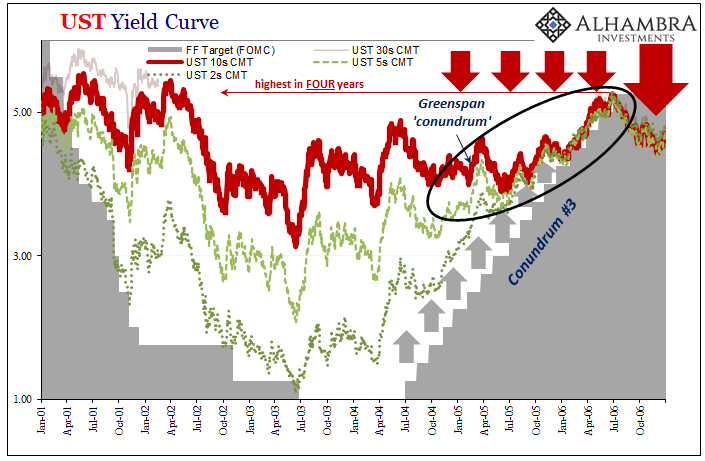

Not even a year into the cycle, however, again Economists were stumped. The Fed was raising rates but LT bond yields just weren’t buying it; on the contrary, the bid for safety and liquidity confounded these rate hikes. As Chairman Greenspan claimed while at the Capitol, the yield curve, “can be thought of as an average of ten consecutive one-year forward rates.”

Therefore, the Fed starts hiking and the entire yield curve is expected to respond, to dutifully obey what everyone including Congress has been told is its master, Master Alan. This wasn’t happening.

On the contrary, as ST rates including UST notes toward the front of the yield curve marched upward, LT rates starting at the 7s and out were lower by February 2005 than they had been in June 2004. Dancing his commentary out from fedspeak, Mr. Greenspan’s meaning became very plain all of a sudden when the topic shifted to bond yields:

For the moment, the broadly unanticipated behavior of world bond markets remains a conundrum. Bond price movements may be a short-term aberration, but it will be some time before we are able to better judge the forces underlying recent experience.

As I said at the beginning, the “maestro” was being deceptive on purpose; to make it appear to Congress as if this was some new development that took everyone by surprise.

It wasn’t.

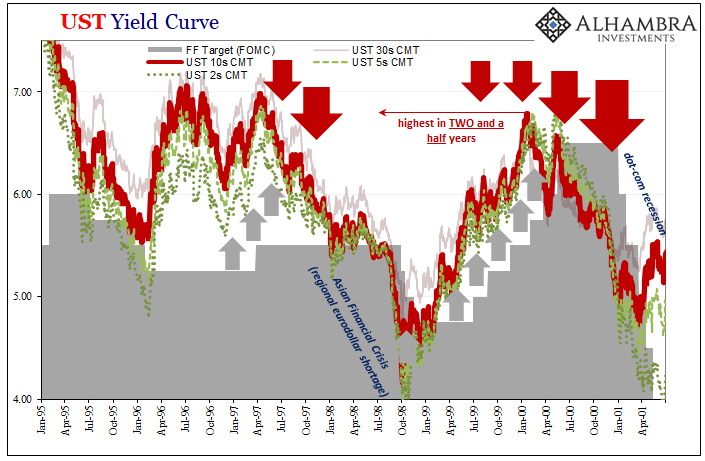

The “conundrum” had already happened to Greenspan’s Fed – twice! – in a matter of several years just a few years before his February 2005 obfuscation. In both cases, an overactive official inflation fear had prompted “hawkish” policy shifts including rate hikes which were vehemently, publicly, ultimately correctly resisted by LT bond yields.

Bonds saw the Asian Financial Crisis coming in a way that no one at the Fed had, and then the 1999 inflation scare was promptly forgotten when the subsequent rate hikes in 2000 blew up in everyone’s face as 2001’s dot-com recession.

Thus, by February ’05 the Federal Reserve’s revered Chairman judged it was far better to lie in front of Congress rather than admit LT yields had bested these “best and brightest” Economists twice already. With the housing bubble raging and that kind of track record, you can see why Dear Alan played it the way he did; better to be thought unprepared for “unanticipated behavior” than confess how bonds knew better than he did and what they know when these things happen isn’t for good things.

Without having any sort of monetary proficiency, contrary to everything we’re taught and told, these statisticians-who-play-central-bankers-on-TV have to rely instead on “discretionary” workarounds. Rather than citing the idea of too much money as the reason for inflation caution from the Fed June 2004 and onward, instead Greenspan told everyone:

Whether inflation actually rises in the wake of slowing productivity growth, however, will depend on the rate of growth of labor compensation and the ability and willingness of firms to pass on higher costs to their customers. That, in turn, will depend on the degree of utilization of resources and how monetary policymakers respond.

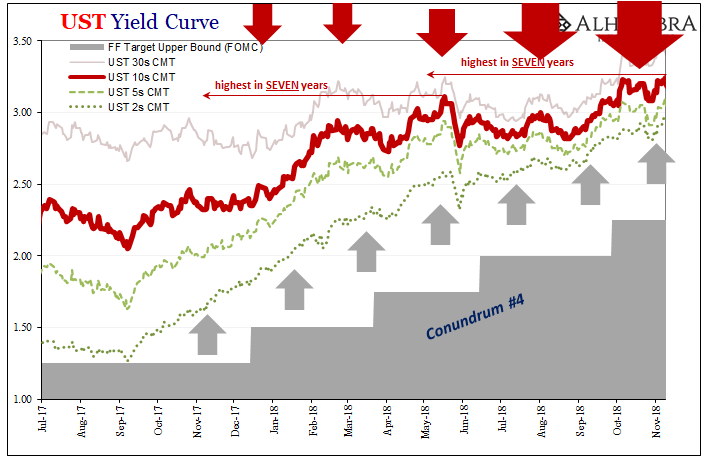

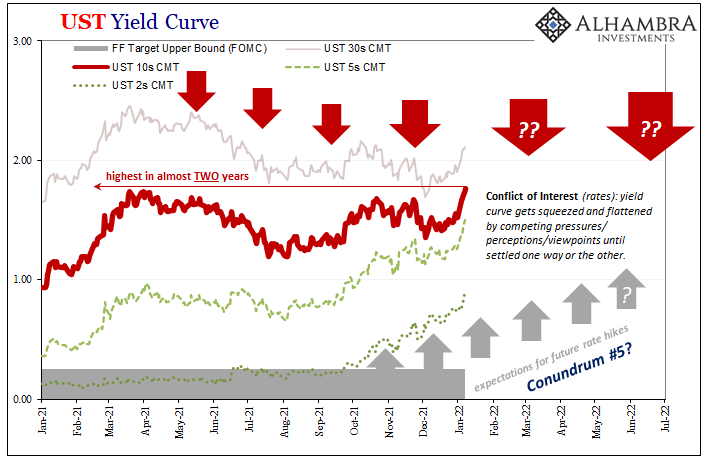

Basically, the same convoluted backdoor nonsense as Jay Powell’s Fed is right now using trying to justify current hawkishness leading to his own conundrum; actually, Powell’s second, as discussed last week; fifth, maybe, overall. Tight labor market, wages, blah, blah, blah.

Is there too much money? They (still) have no idea.

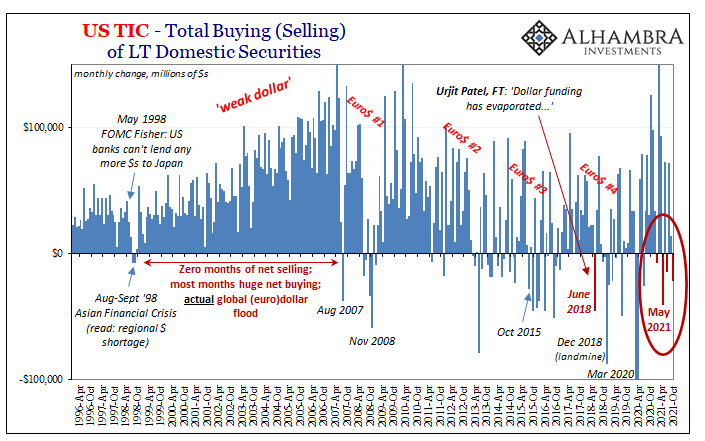

Contrary to popular belief, the rate cuts ‘01 to ’03 had not been the reason for the housing bubble; it had shown up almost a decade before, all the way back to ‘95. The eurodollar system not the Fed had “printed the money” as credit denominated in dollars exploded globally. Thus, the flattening then inverted yield curve ’04 to ’06 was the bond market recognizing well ahead of time the very real dangers should “something” go wrong – and the Fed literally out of its depth and obviously unwilling, perhaps unable, to ever catch up.

What had happened in each “conundrum” was the same thing we’d see again in 2018; the Fed can, for a time, influence the short end of the curve up to its middle, or belly, then, contrary to Greenspan’s “series of one-year forwards” nonsense, it becomes all Irving Fisher from there onward.

From 2004-06, LT bond yields rose only modestly, so that didn’t actually solve the “conundrum” even if the 10-year benchmark managed a four year high by early 2006; in 2017 and 2018, same thing, even though a seven-year high by October ’18.

So, if the market judges that growth and inflation prospects aren’t actually great over the intermediate and longer term, this will be reflected in LT bond yields that stay relatively low even if they rise a small amount due to this “hawkish” pressure from below – up until a point (landmine) when the Fisherian perspective takes over regardless of the Fed’s outlook, policy positions, or any kind of Congressional testimony.

This had been the case in ’97 turning ‘98; again in ’99 and early ’00; the third not first “conundrum” by ’04 and lasting until ’06; a fourth in ’17 and ’18 breaking everything down in ’19; and now, perhaps, a fifth developing late in ’21 and so far of ’22.

While Alan Greenspan wanted the world to believe 2005 was the first time, it really hadn’t been and even though this sordid history goes back from today a quarter century, there is no sign anywhere – Fed, media, Economics – useful lessons have been learned from these repeated episodes even though this really isn’t complicated.

Monetary and financial therefore economic (small “e”) illiteracy is a choice. Conundrum is just an unnecessarily fancy way of attempting to dismiss this conflict of interest rates policymakers always lose.

Stay In Touch