Rate of change in economy goes down, rate of change in politics goes way up.

The latter half of the formula, politics, historically applies to the internal makeup and stability of whatever country or system experiencing the macro drought as well as to its neighbors. Going back through time, any prolonged period when the economy was in distress (which typically had meant famine rather than widespread unemployment) there you’ll find conflict.

None of this is to excuse what the Russian’s are up to, or may yet get up to. On the contrary, to understand why and why now it’s a useful exercise to take a peek behind what may be driving such an aggressive posture.

It may seem like eons ago, and that’s the point, but Russia was once considered a solid founding member of the BRICS. Yeah, that Russia was held up alongside China, India, and Brazil not for reasons of nuclear arsenals or aging capital warships. The Russian economy had proven itself as much a beneficiary of the eurodollar mania as anywhere else.

Though China had been the posterchild for the successes of pre-2008 globalization, the gains were indeed widespread. They even included the Russians who as late as the mid-nineties were still trying to survive the devastating effects of post-Soviet currency collapse and economic ruin.

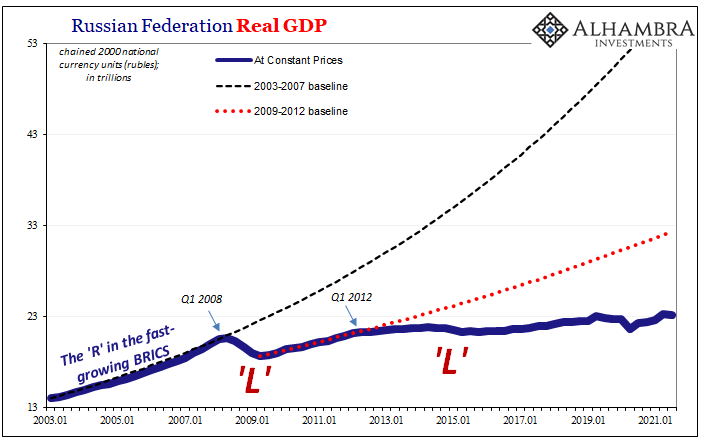

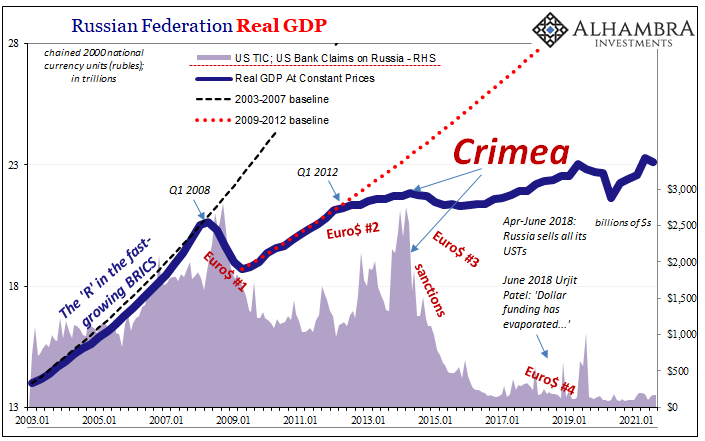

Yet, by the middle 2000’s things were definitely on the upswing for Moscow. In the bubbly years between 2002 and 2008, real GDP growth (measured in chained 2000 rubles) averaged 7.8% per year. These weren’t the results of your father’s Russia, a new paradigm seemed to have taken hold justifying the inclusion of Russian with the other fast-growing contemporaries.

However, as you can plainly see above, all that just “vanished.” One day, on the road to prosperity. The next (or after a few years), where’d it all go? The setback in 2009 understandable to a point, that whole Global Financial Crisis thing-y; afterward, though, zero answers.

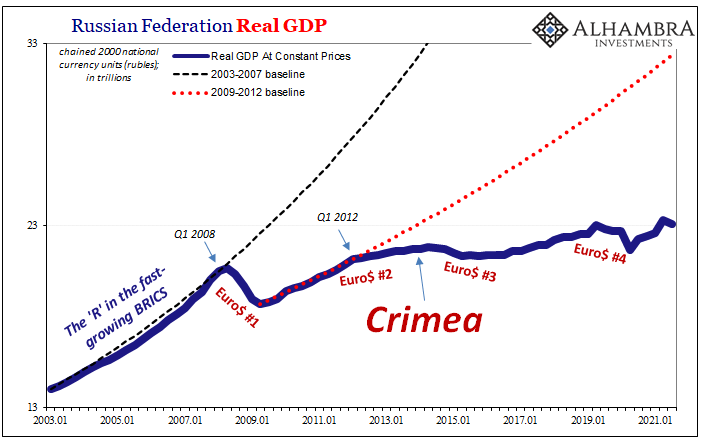

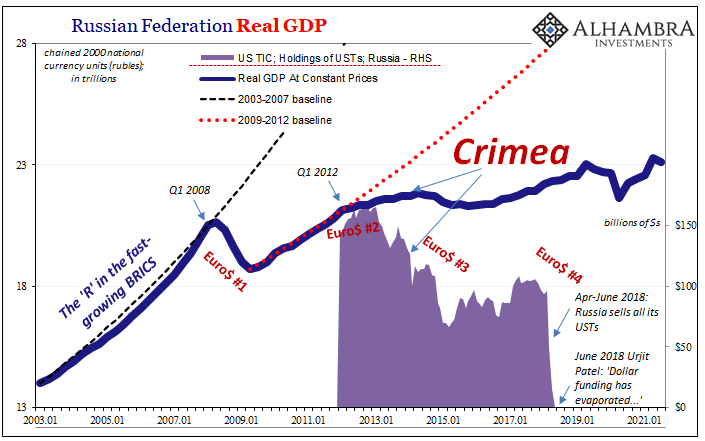

By 2014, craven eyes were glued on the Crimea. Sanctions inevitably followed the intervention, including more extreme restrictions placed on US banks (outside eurodollar banks, another matter).

These did not nor do they now describe the real menace for Russia as it again takes aim at perhaps the whole of Ukraine; the eurodollar does. Like China or Brazil, Euro$ #2 had already drove the stake through the heart of whatever remained of the BRICS; especially its “R.”

They were already seriously selling out of their USTs long before February 2014 when hostilities commenced. Instead, the Russians had made a point of trying to find other means of eurodollar access even if would’ve led to opening up Vnesheconombank, Putin’s so-called slush fund development bank.

Russia was bleeding access like economic growth which is really the point. The very minor upswing in both during 2017’s globally synchronized growth demonstrated that post-February 2014 sanctions don’t really explain the Russian plight.

Instead, these had merely pressed a bad situation further in the wrong direction by removing one final margin for eurodollar error after they were installed (and this is by no means a criticism of the political rationale behind those sanctions).

By the time Summer 2018 rolled around, Euro$ #4 would end up hitting the Russian economy (especially second half of 2019) hard, without available alternatives authorities desperately looked toward extraordinary means to circumvent their lack of elasticity with regard to the world’s reserve currency regime (eurodollar, not dollar).

Out of options, or close to it, the Russians at Vnesheconombank undoubtedly with approval from Putin suddenly got very interested in digital currency technology at a time when the rest of the global public sector was frowning on it. Hardly anyone noticed; wintertime in crypto-land.

As such, the Russian economy fell back into recession late in 2018, rebounded only for one quarter in 2019, and then more recession for the final half of that year plus the first quarter of 2020.

As of the third quarter last year, real GDP over there is just 12.7% higher than it had been in Q1 2008. Maybe that doesn’t sound too bad, but this works out to an annual rate of 0.9% per year…for thirteen and a half years. From nearly eight to less than one in what sure appears to be a permanent shock across the Russian landscape.

But it’s not just Russia, is it?

The promise of digital currencies and equally the unwelcome potential for real shooting conflict, each a reflection of the same underlying issue: inelasticity in the global reserve. What once had been a full-fledged member of the BRICS is today on the cusp of unthinkable tragedy; leaving the world to only pray cooler heads prevail.

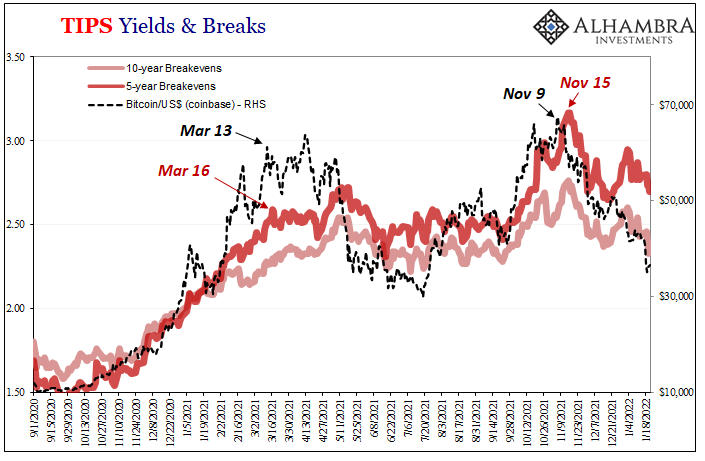

And no one is looking into this hiding-in-plain-sight connection; not even digital currency enthusiasts most of whom still think and trade of the dollar’s collapse from too many of them rather than the open door of inelasticity unleashing global plague via eurodollar breakdown.

Russia has no dollars available, really has no way (apart from oil, and that’s not exactly filling their coffers even as global prices rebound) to get more of them, and now its domestic economy stumbles badly into the second half of last year which was supposed to have been a full-on inflationary global renaissance.

Again, none of this is to excuse what trouble appears to be unfolding; just might explain a lot.

Though it may read like it, I’m not actually claiming these factors add up to the primary cause for Moscow’s current bellicosity. As always, conflict is the product of an array of complex and intricate motives; political, national, and just plain human nature.

Fourteen now almost fifteen years of intractable dollar issue, particularly since 2011, it goes right along with Russian economic stagnation and does provide useful background for maybe why those motives seem so overwhelming at times such as these. Peace generally reigned (a few notable exceptions) while the eurodollar spread the positive fruits of globalization all over the world – including into the formerly moribund former Soviet Union.

A once promising future that just disappeared for reasons never explained. A political playbook as old as human civilization, blame the other guy (or guys). As absolutely disruptive and destabilizing as this would be – and is (see: Xi) – anywhere else, of all places Russia.

Stay In Touch