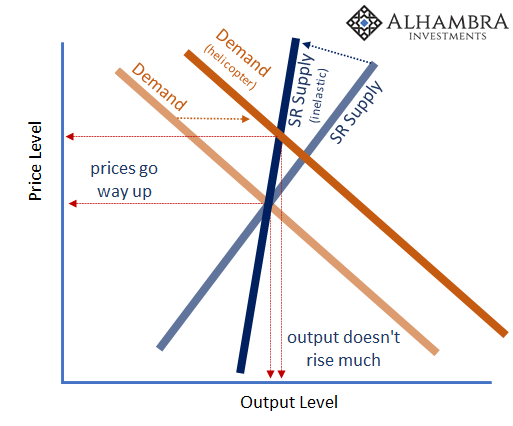

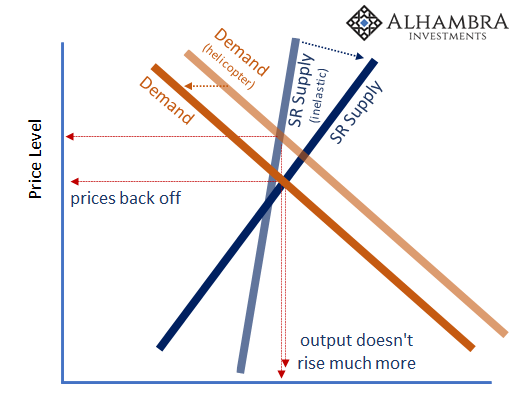

This thing, this massive supply disruption is a perfect example of a positive feedback loop. It began with government (over)reaction to COVID, as noted here impacting both supply and demand. Those two curves have behaved in classic fashion, inelastic supply unable to efficiently respond to an artificial outward shift in demand. The resulting impact price-wise as pure economics (small “e”).

A huge piece of inelastic supply, though, came to be tied to – or tied up in – the general conveyance of goods moving through the supply chain. It may have been difficult for producers to initially crank their efforts back up, yet they managed to do so at any rate. As they did, however, the initial imbalance completely changed the dynamics insofar as shipping goods especially into the US via its West Coast operations. As the demand for goods came back, quite naturally the demand for shipping goods rose, too. The price of shipping like those for goods responded positively, particularly the rate paid to use containers. At some point rather early on last year, the container price soared enough to cause some shippers to rethink their activities – and not in a good way, systemically speaking.

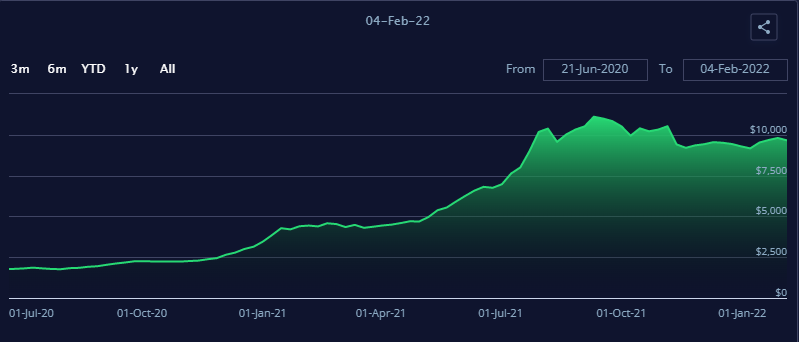

As the demand for goods came back, quite naturally the demand for shipping goods rose, too. The price of shipping like those for goods responded positively, particularly the rate paid to use containers. At some point rather early on last year, the container price soared enough to cause some shippers to rethink their activities – and not in a good way, systemically speaking.

Typically, their big boats offload cargo coming in from China and Asia but then wait around to take back with them some US exports along with a whole bunch of empties. With backups plaguing these same facilities, and with container prices exploding, carriers began to sail out of LA or Long Beach without waiting around.

Given how high shipping rates had gone, you could understand why ship owners weren’t too interested in having their ships sit in port waiting around for empties to be loaded – and no real idea how long this would take. Rather than wait, leave port as soon as possible so as to squeeze another sailing from China back to the US taking full advantage of such high shipping and container prices.

Freightos Global Container Index (FBX) https://fbx.freightos.com/

The economics practically demanded this positive feedback loop.

These so-called blank sailings caused more empty containers to pile up, adding to the difficulties Chinese exporters were experiencing in order to obtain them. Prices for containers skyrocketed even more, adding to the already-fat incentives for shippers to conduct blank sailings, stranding thousands upon thousands of additional empty containers around the LA region.

The more the empties piled up, the higher the delays (and not just for boats, also trucks and railroad cars who had to offload an empty in order to then take a full one coming in), adding to the self-reinforcing cycle of blank sailings.

“Our biggest problem by far is empty shipping containers,” Matt Schrap, CEO of the Harbor Trucking Association, a coalition of intermodal carriers serving America’s West Coast ports, told Xinhua. “They are the bottleneck that is sinking the global supply chain.”

With Christmas “forced” to come early, anyone and everyone convinced to get holiday business done well in advance to ensure some level of availability for rabid US consumers, it all came to a climax around late October.

It was around that same time authorities decided action was needed to do something about the container imbalance. LA’s Harbor Commission unanimously voted to implement a “dwell fee”, announced on October 25.

For any container moved by truck, after “dwelling” idle for nine days authorities would impose this $100 fee (six days for containers going by rail). For every additional dwell day, the cost goes up another $100 per.

However, though it was approved months ago, the Commission’s escalating surcharge scheme has never been implemented. Each time the topic comes up, it gets pushed back and held back as a threat. For one thing, dating back to late October, the number of empties has substantially declined and so have stranded cargoes.

The so-called dwell time a container sits around on average before it gets picked up has fallen by more than half from late October and there are no longer dozens of ships at anchor outside the ports waiting for weeks before they can berth and offload their cargo.

While some of the reduction in the logjam of boats lazing off the West Coast can be attributed to better traffic management (having inbound vessels slow down and take slightly longer in transit), the knock-on effects have been widespread.

Going back to when the fee was initially rolled out on October 25, POLA [Port of LA] and POLB [Port of Long Beach] said that the ports have seen a cumulative 62% decline in the amount of aging cargo on their docks, a tally which has trended up going back to the initial announcement of this fee.

And the estimated number of vacant containers at LA alone has been cut from 90,000 down to around 72,000 as of mid-January.

The trend in container prices has confirmed the general outlines of this West Coast case. And all of this was predicted by one shipping insider interviewed by the Financial Times’ John Dizard all the way back…in October.

“Lars Jensen, a container specialist with Vespucci Maritime in Copenhagen, did very well during the pandemic. I caught him in Kenya just as he was disconnecting from the grid for a long anticipated safari. ‘I would agree with you that it’s over,’ he said.”

There remains a long way to go in more completely untangling this mess (and this is only part of it, a big part, sure, though far from the whole problem). To that end, one expert I spoke to today said to expect the dwell fee to be imposed in the near future. And if it does get activated, presume even more diligence on the part of domestic parties.

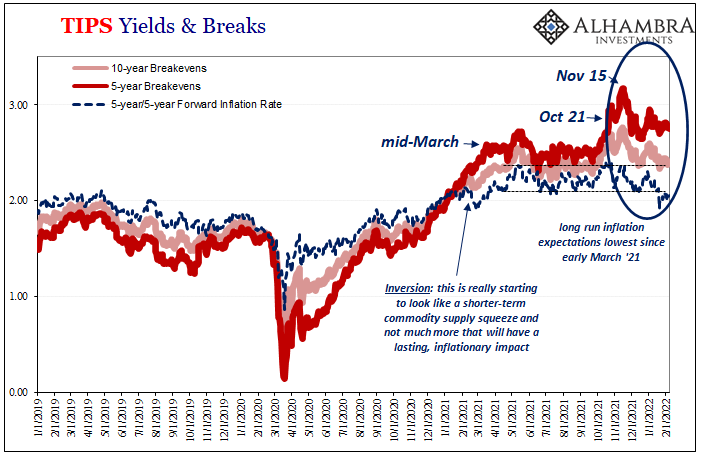

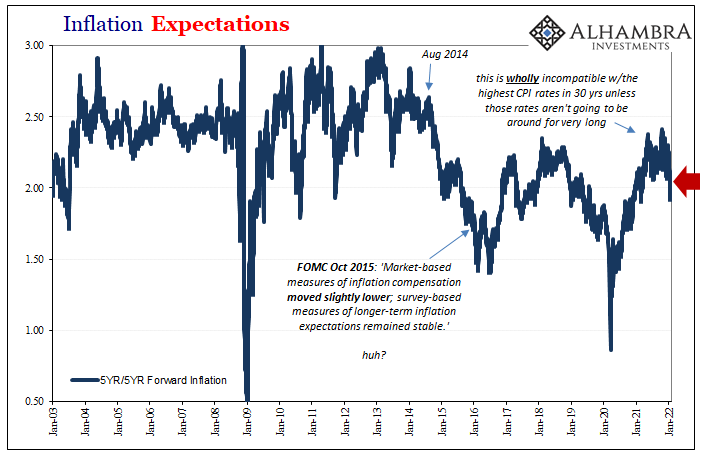

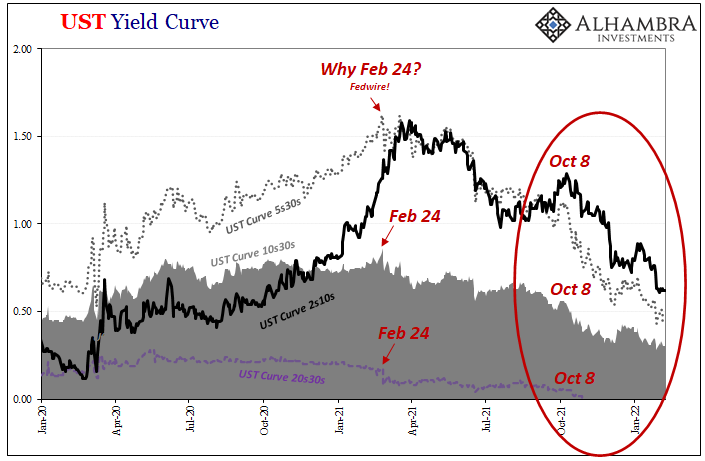

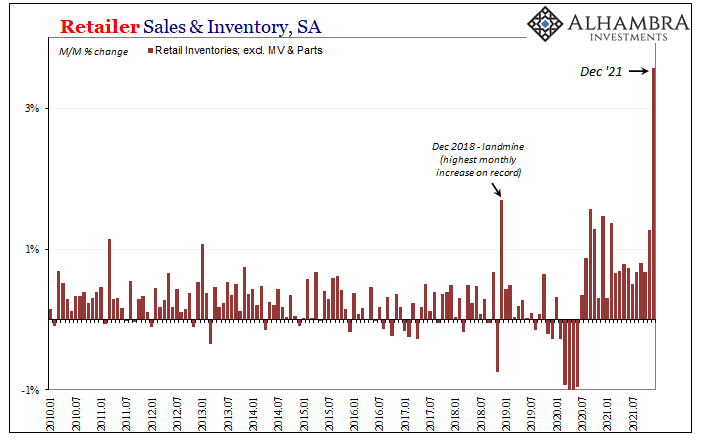

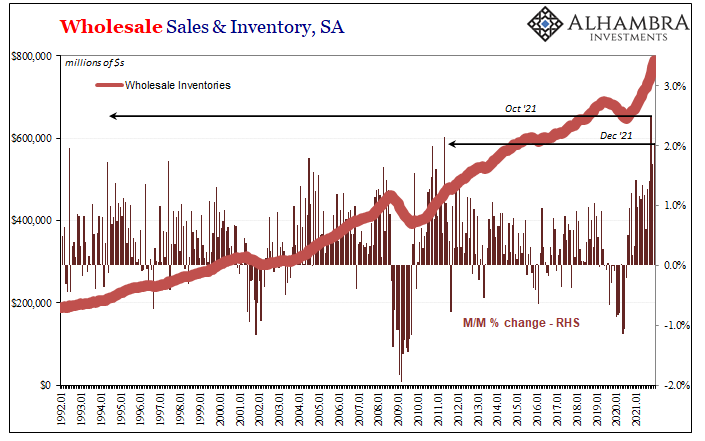

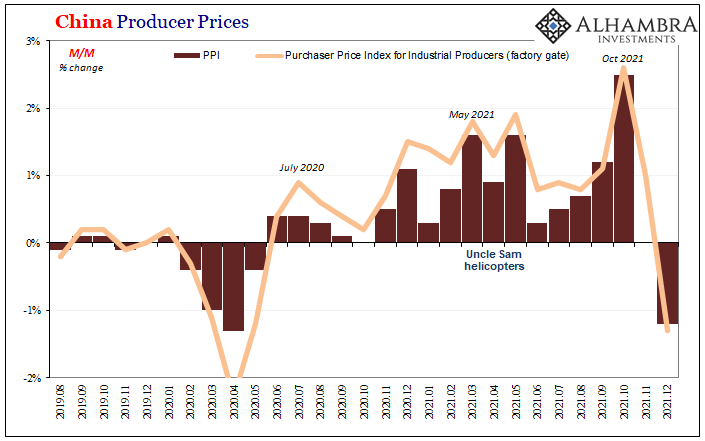

With shipping contributing so much to last year’s “inflation” (supply shock, not money) via inelasticity and the self-reinforcing cost(s) spiral, so many indications pointing to October as a possible apex in this harmful trend, could the slowly emerging downside thereby explain all of these:

After all, the higher oil prices kept going since December, the more you’d otherwise expect TIPS market inflation expectations to track closely with them. They’ve gone the other way.

There’s also more than a tiny hint of demand behind the thus far limited though clear improvement in the supply situation. It’s not just market-based inflation expectations which have correlated with the favorable macro trend in container prices, blank sails, and fewer empties; the flattening yield curve would also suggest the potential for softer demand to contribute its own to the probabilities for lower and transitory “inflation.”

All of which risks leaving Jay Powell out in the dark, cold night of a what he today worries is an overheating economy. Even the market reaction to last week’s payroll report nicely fits in with all these factors; the mess of labor market data will only encourage the FOMC’s rate hikes while at the same time many points in the real economy aren’t at all following along that interpretation. Including payrolls.

The net result is flat and then flat some more.

Stay In Touch