Nobody, and I mean nobody, does premature celebrations like central bankers. When it comes to their non-money monetary policies and the inflation they seek to create from them, time and again officials in every jurisdiction spike the ball at least 30 yards before they reach the endzone. Whenever one or another consumer price measure ticks up, or accelerates dramatically as in the US and Europe, these Economists extrapolate forward in a straight line.

The reasons they all do this is understandable if still disgraceful. Inflation is money, therefore a true central bank should be able to judge whether or not there is too much. If there is, inflation’s going to be coming unless some intervention in the real money system.

These modern “central banks” don’t do money and wouldn’t even know where to begin. Therefore, they have to find some way to work around this fundamental blind spot. Instead, policymakers attempt to reverse engineer their way into the inflation ballpark (they hope) which necessitates extrapolating out into the future even the smallest blip.

Any bump in any CPI is immediately turned into confirmation bias.

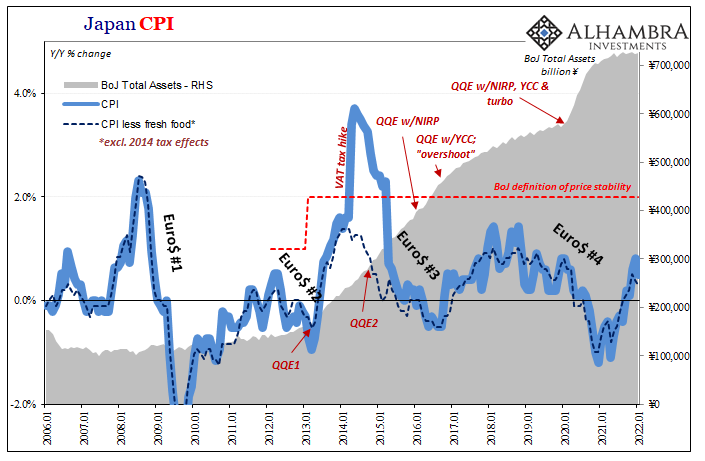

One of the more infamous examples was Japan circa early 2018. Thinking they’d done it after a decade and a half of trying, the “exit” seemed within authorities’ collective grasp for the first time…ever.

On March 2nd [2018] the Bank of Japan’s Governor quite purposefully let it be known that policymakers were considering an end to QQE. After just about five years of it by then, there was growing confidence it was nearing its goals.

The following month, on April 3rd, Kuroda went further. Clearly adoring the positively glowing stories written about his bold efforts and stubborn persistence, BoJ’s top official specifically stated that they were talking about the exit. “Internally we’re conducting various discussions,” he said, having been formally re-appointed to another term just weeks before.

Those things never happened because while Japan’s top central banker had already filled the balloons up with helium and reserved space for his parade’s rout, the Japanese economy, indeed the whole global system, was already falling off – and not for the first time.

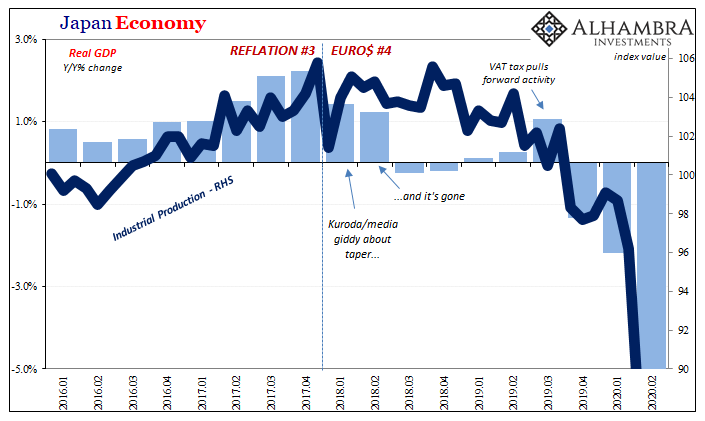

Distracted by the bright shiny object of a moderately positive CPI, none of BoJ’s staff nor any of its officials had noticed the already-in-progress globally synchronized downturn. It wouldn’t stay merely a downturn for long in Japan, either, as recessions (plural) would plague the country repeatedly throughout the rest of 2018 right on through the end of 2019, all before COVID ever showed up.

Needless to say, the consumer price index never once reached the 2% target – the core rate, excluding prices of fresh food, only ever made it halfway and only then on just two occasions before everything decelerated into the morass of 2019.

The Japanese debacle was hardly an isolated case – both Jay Powell and Mario Draghi ended up being embarrassed in the same fashion at the same time as Kuroda (because the world economy is synchronized by the eurodollar, the very money “central bankers” don’t/can’t ever factor).

Draghi had terminated Europe’s QE at the end of 2018, contemplated rate hikes for 2019 only to have to restart QE (not that it did anything) all over again that September.

America’s Powell was hiking rates undeterred throughout 2018 and various market warnings only to turn around and cut them after July 2019.

History, as you’re well aware, repeats because “central bankers” don’t know what the hell they are doing when it comes to money, inflation, and economy.

Here we are yet again, the world facing the same position. The FOMC terminating QE, rate hikes to begin in less than a month. Europe’s ECB lagging that plan only slightly.

And Japan? Well:

Bank of Japan policymakers are debating how soon they can start telegraphing an eventual interest rate hike, which could come even before inflation hits the bank’s 2% target, sources say, emboldened by broadening price rises and a more hawkish Federal Reserve.

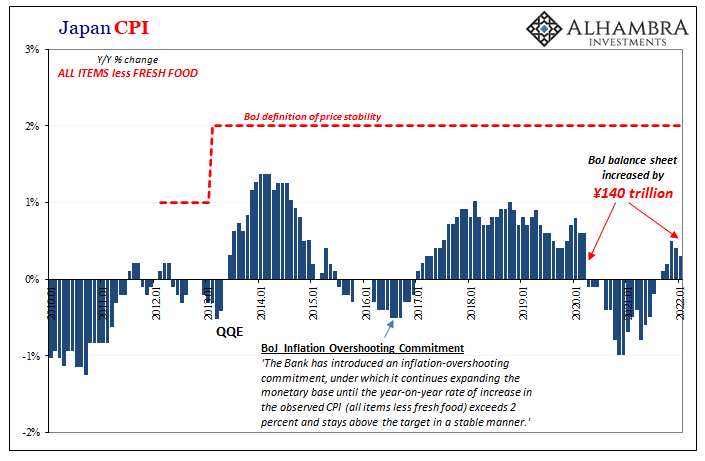

This renewed celebratory thought-process was brought back up in the middle of last month – before Japan’s CPI data for the month of January was released this month showing more problems of the not-inflation variety.

According to Japan’s Official Statistics bureau, or e-Stat, consumer prices had advanced 0.8% year-over-year in December 2021 – which is what got everyone so excited in the first place. But for January, it decelerated to just 0.5%; either “unexpectedly” or due to omicron, going by mainstream interpretation.

The core CPI rate, which is what the BoJ uses to for its target, that one had peaked back in November last year at a quarter of the official 2% goal. From that lackluster 0.5% annual rate to 0.4% annual in December to then 0.3% by last month; there seems to be a trend developing.

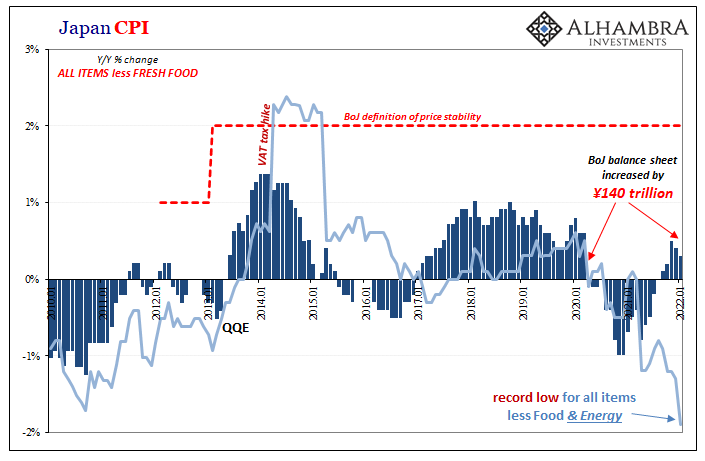

And the data only gets worse. The few parts of Japan’s consumer bucket even moderately experiencing price pressures are food and energy. Excluding those, all other consumer prices have been falling at increasingly alarming rates. In fact, for this particular series, -1.9% year-over-year is a record low.

Not inflation.

What did happen in Japan to its consumer prices? The global supply shock bringing with it a modicum of the money illusion caused by that same imbalance (and neither due to QQE or fiscal interventions) began to wane. The best example of this illusion and its potential downside can be found in the recent history behind Japan’s trade balances and results.

Wouldn’t you know it, the Japanese tend to import a ton of…food and energy. The latter is obvious to most people, while estimates show about 60% of what food people living there consumer comes from outside of Japan.

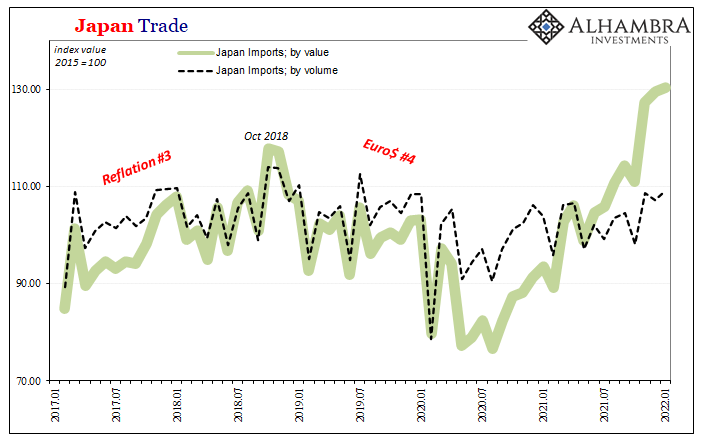

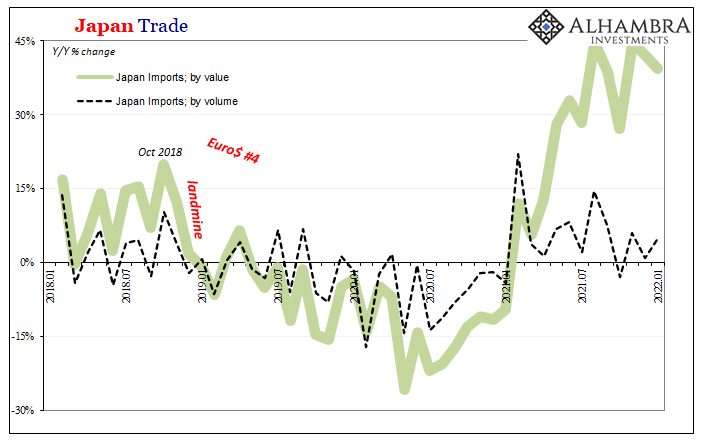

So, when the country’s Ministry of Finance estimated January imports into the island nation were 40% higher than they had been in January 2021, it did not indicate how the nation’s people might have become voracious overeaters (we know it couldn’t have been from simply more people) while also driving their automobiles 24/7.

No. The global supply shock had spiked prices of both categories of goods, meaning that in value terms imports were 40% higher and have been since early last year.

In actual volume, the increase wasn’t even 5%!

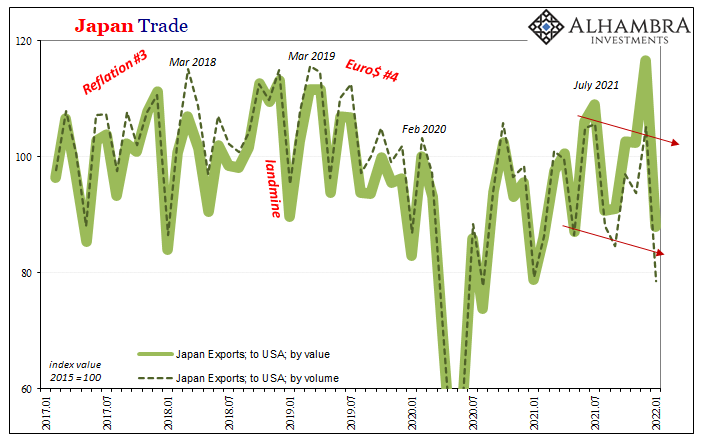

This massive discrepancy showed up around, no surprise, March and April 2021 (thanks to, primary among other factors, Uncle Sam’s helicopters shifting the global demand curve temporarily to the right when at the same time the global supply curve and shipping capacities were most inelastic). In fact, by volume terms, Japan is importing less – and has been for several years – than it was back when Kuroda was last contemplating his parade.

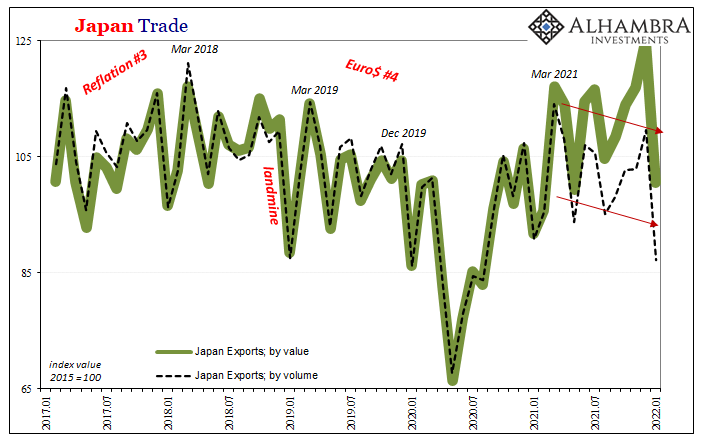

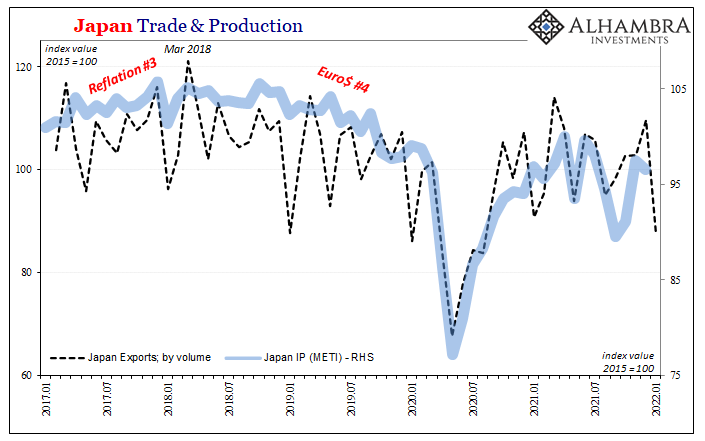

Where this gets more globally interesting is over on the side of Japan’s export situation. Same money illusion:

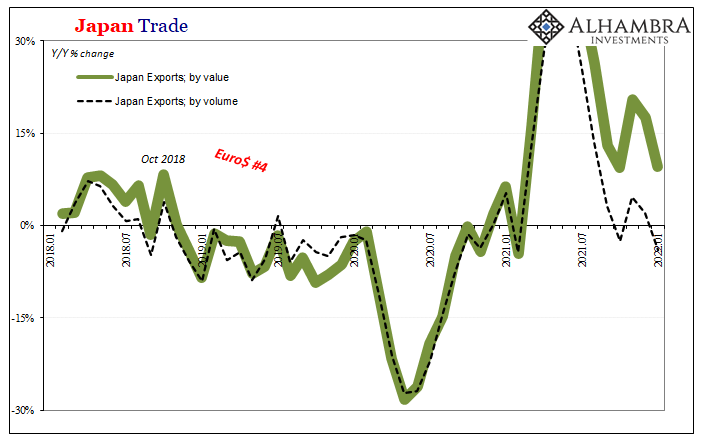

While the Ministry of Finance thinks exports by value were up by almost double-digits in January, a little less than 10% year-over-year, by volume they declined a substantial 4%. And it was not the first month to show a negative comparison, either, rather the second time since September. The trend is, by this point, rather obvious.

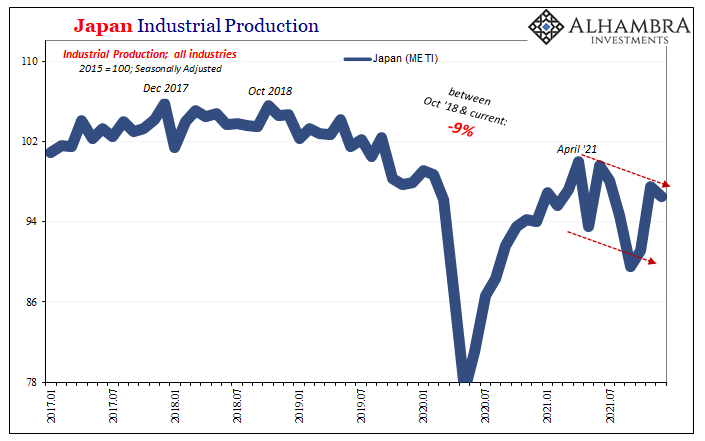

Because Japan isn’t exporting a lot more goods by volume, Japan doesn’t need to produce a whole lot more goods, either. Japanese Industrial Production (IP there is almost all manufacturing) has been waning since, yes, last April.

Now where Kuroda’s conundrum meets Jay Powell’s is right there on the chart immediately above. By tally of Japanese exports to the US, American demand for what Japan makes seems to have slowed down (as Maersk had shown) throughout the last half of last year – even though by price (value) it would seem the flow of goods continued to rise. In fact, exports by volume declined in four out of the last five months up to and including last month.

Are all these central bankers making the same mistake, which happens to also be the same one they have committed repeatedly throughout recent history (including 2018-19)? At the same time each is looking ahead to inflationary potential in their own backyards and “tightening” policies because of their assumptions, they seem to be doing so into yet another potential globally synchronized slowdown or worse.

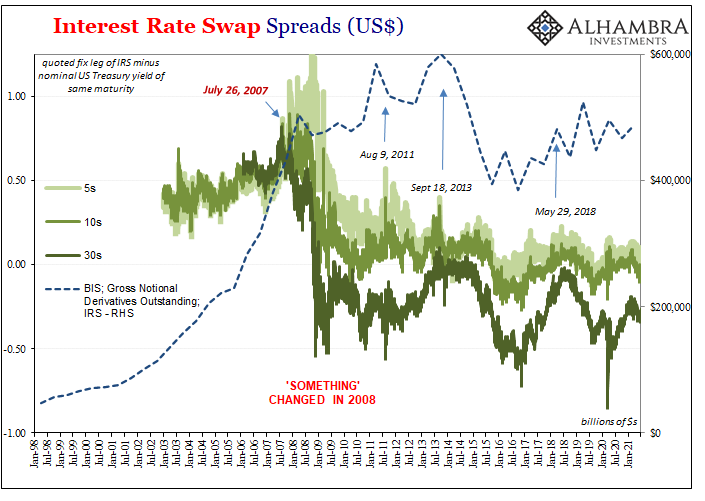

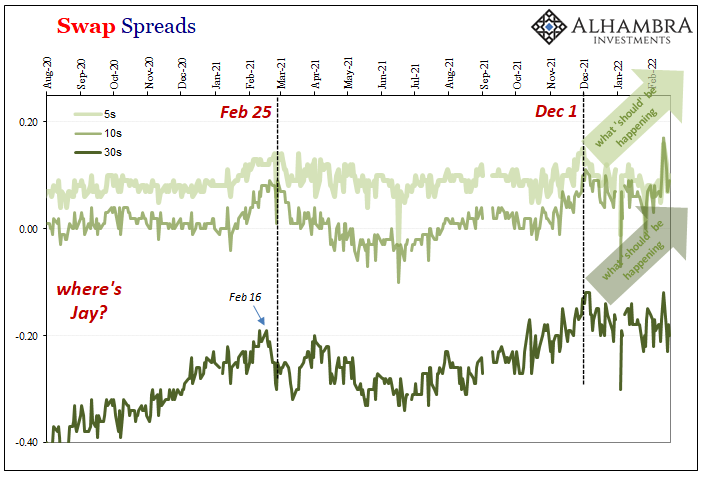

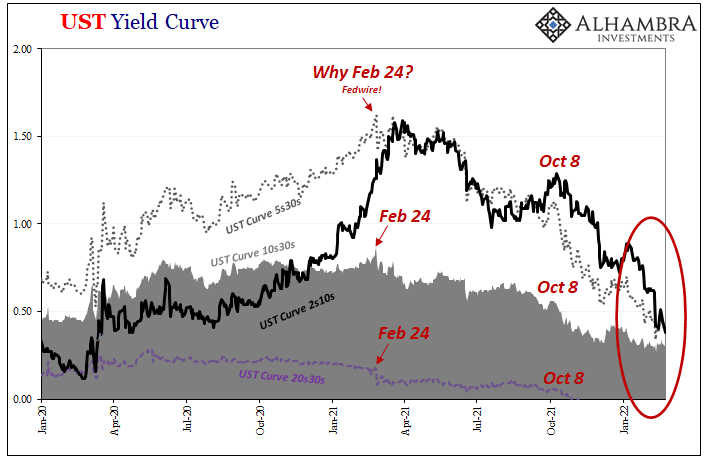

Given all these things and more (like China), swap spreads, eurodollar futures, dramatically flatter US Treasury yield curve, etc., these all make a ton of sense.

Non-money monetary policies, however, they never do and it doesn’t seem to matter where or when.

Stay In Touch