Have European banks begun to lend in a way that will lead to actual inflation? For Europe’s central bankers, this is a huge question. For so many years despite almost constant QE, banks have consistently refused to do so. Even with supercharged asset purchases begun in 2020, there still hasn’t been any correlation between ECB activities and bank lending.

This is actually the consistent history of all QEs in all places.

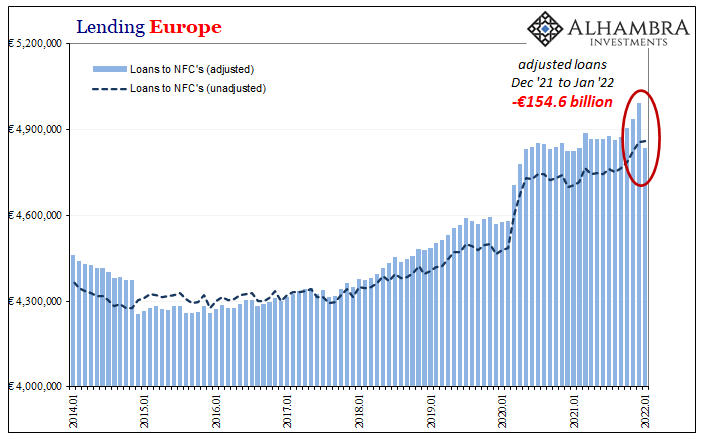

In September last year, bank lending did tick higher, mainly from loans given to Non-Financial Corporations (NFC). This would be doubly good since credit to European businesses has been atrociously weak not accidentally going all the way back to 2008. The lack of access – because banks don’t/can’t lend – has been the primary point of failure in that real economy.

Businesses that can’t get loans can’t invest, the so-called supply side of the economy suffers as does labor utilization.

Getting banks to extend loans to NFCs, particularly small and medium-sized ones (the very groups suffering the most because of systemic liquidity risks), has been a primary focus of the ECB for many years.

Did it finally pay off?

While, again, bank lending to all NFCs rose in the final three months of 2021 (below), it really wasn’t all that much. In the grand scheme of inflation and catching up the real economy to something even in the same ballpark as normal, it was at best a tiny blip.

Furthermore, there is every reason to believe (start with the timing) that the increase was due mostly to companies seeking to get loans done ahead of rate hikes (and the popular misperception, even in professional settings, central bank rate hikes extend into credit market rates). With hawkishness becoming a definite “thing” around September last year, if this was the reason for burst of lending it would mean little more than pulling forward activity that otherwise would’ve happened early in 2022.

The ECB’s loan data for January 2022 does, indeed, indicate that, at the very least, no additional credit got extended to NFCs. This potentially (for a single month) indicates that last year’s minor blip really may have been related to cost/rate considerations.

Wait a darn minute, I hear you saying, the chart immediately above draws two loan series and it’s only the second of them which shows lending to NFCs in January being essentially flat to December. The other one, already circled and annotated, loudly declares that lending dropped by an enormous €155 billion in just the one month.

You’ve also no doubt noticed how one series says “unadjusted” while the other is “adjusted.” This immediately begs the question, adjusted by or for what?

To answer that question, and get to what might have happened in the adjusted loan category and why it is suddenly so different than unadjusted, we have to take a detour down the rabbit hole of QEs, collateral, securitizations, and, just maybe, Russia and Euroclear.

We’ll start out in the world of securitization – European version(s).

The entire purpose of securitization worldwide was and is, as the name lays out, to create marketable securities from otherwise illiquid assets, transforming mostly individual loans into standardized liquid instruments. While this would make it possible, in theory, to estimate and quantify the financial characteristics of the underlying assets (it didn’t work out so good in practice), once coined (pun intended) those liquid securities could then be used as collateral unlocking the most efficient, highest leverage form of short-term funding.

Repo.

In fact, combining the math behind risk calculations with this repo opportunity had meant, effectively, taking illiquid, inert individual loans and creating substantial new volumes of pristine collateral from them; at least before 2008. The process had been a veritable collateral factory.

And it all broke down during the first Global Financial Crisis which revealed the weaknesses (and hubris) behind those naïve assumptions. In fact, the most basic characterization of the 2007-09 worldwide monetary run was the sudden collateral shortage brought about by the re-evaluation, then revaluation (haircuts), of all that conjured-by-securitization collateral.

While the Federal Reserve paid almost no attention – during or after – to these destructive and self-feeding global collateral implosions, other central banks such as the ECB were more attuned to the consequences of so much collateral product being rendered, post-crisis, unusable on pre-crisis terms.

They more openly debate and discuss what’s called a “safe asset shortage” and how these might (yeah, not “might”) be a problem for what they also call Securities Financing Transactions, or SFTs.

In fact, upon the eruption of the European “sovereign debt crisis” in 2010 so closely following the first GFC, and with so much previously securitized debt instruments not really negotiable on the same terms for SFTs, the “safe asset shortage” was already a huge deficit before several other kinds of sovereign bonds (PIIGS) were thrown into the unusable category, too.

This only amplified the scarcity of collateral forced on the (global) system. Europe’s central bank responded to the systemic challenge by channeling private securitization toward its own balance sheet. As two ECB researchers presented for the BIS at a 2016 conference:

With the onset of the financial crisis however, most securitisation activity in the euro area was related to the need to create collateral for central bank borrowing. Instead of being placed with investors, the instruments resulting from the securitisation transactions were “retained” by banks.

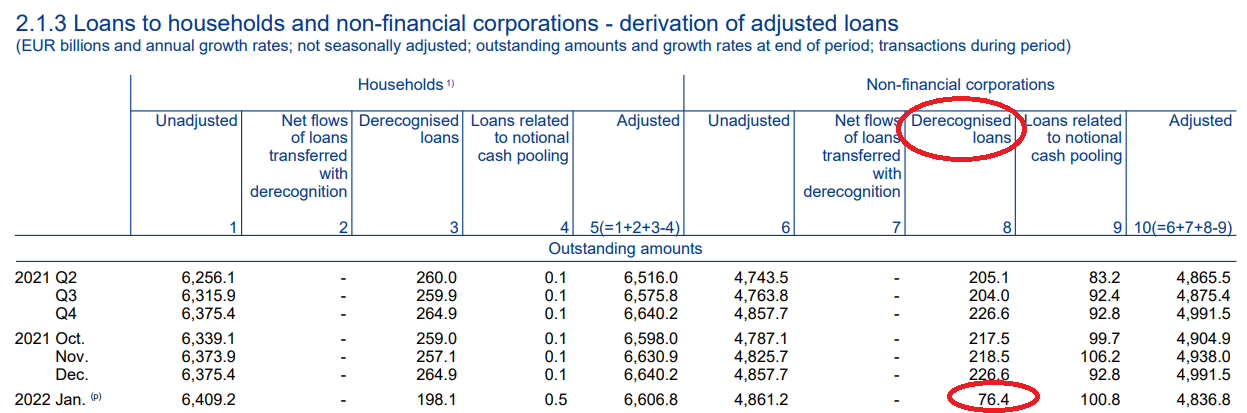

Not only had private banks been handed another dangerous systemic liquidity dilemma, it also presented European monetary authorities with a data collection challenge (the purpose of the above presentation at the BIS). In short, banks might “derecognize” loans that were packaged into securities and then transferred to the various National Central Banks accepting this other securitized collateral throughout Europe.

If so, then unadjusted loan data wouldn’t necessarily capture the full extent of lending in Europe; the data would instead have to be, well, adjusted:

The adjustment was possible through the collection of data on the net amount of loans transferred from MFI balance sheets during the month in order to correct a negative flow resulting from loan derecognition (or positive flow due to loans being transferred back to the balance sheet).

This, then, explains the difference between the unadjusted loan series and its more comprehensive cousin. Unadjusted lending is attuned by the net flows of loans that are transferred with derecognized assets, any derecognized loans which satisfy certain requirements, and then any loans related to cash pooling which meet other threshold conditions.

For our purposes, we only need focus on the middle one of those.

Normally when you find such a large and abrupt change in any data series let alone one pertaining to loan figures, immediately you suspect something was changed in data collection or a calculation-based discontinuity. In almost every such situation, data providers – here it’s the ECB – are very careful to note any modifications to methodology or the like which makes the data discontinuous.

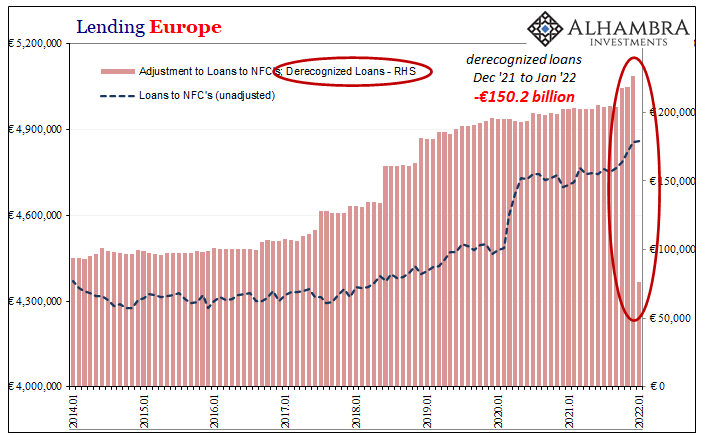

There is none indicated here, meaning that, for reasons that aren’t clear, the ECB’s adjustment factor for derecognized loans dropped by a startling €150.2 billion going from December 2021 to January 2022; accounting for just about the entire decline in the unadjusted loans to NFCs.

Here’s what it looks like in historic time series:

This part is easy; something big happened.

Since around the middle of 2017, the statistical adjustment for derecognized loans, therefore a proxy for what banks might be doing trying to turn securitized illiquid loans to companies into usable collateral to be pledged exclusively with NCBs, roughly doubled – with a coincident rise over the final three months of 2021, too.

So, why the sudden and inordinate collapse in the adjustment factor in January? The ECB supplies no explanation at all.

There are a couple of interpretations we might make in lieu of a direct answer. The most obvious is discussed in the quoted passage above, where banks might have experienced a “positive flow due to loans being transferred back to the balance sheet” during January, necessitating a far smaller positive adjustment factor applied by the ECB.

But that only raises the question of why any let alone so many loans might have been repatriated. And if so, why so much less lending.

From here on I’m going to delve into pure speculation. There are a few “coincidences” that plead for at least some consideration.

If that’s not your interest, then you can end the story here by noting what’s different in the figures and leaving apart any query into why it changed. For the ongoing inflation/lending story, January isn’t what you’d expect if European banks were suddenly embracing the overheating economy; first, lending didn’t pick up all that much, and then, for the first month of 2022, it sure didn’t stay up.

For anyone wanting to go further and hypothesize, realizing that while there may be dots to connect, any connections we make here are tenuous at least until confirmed or denied later on.

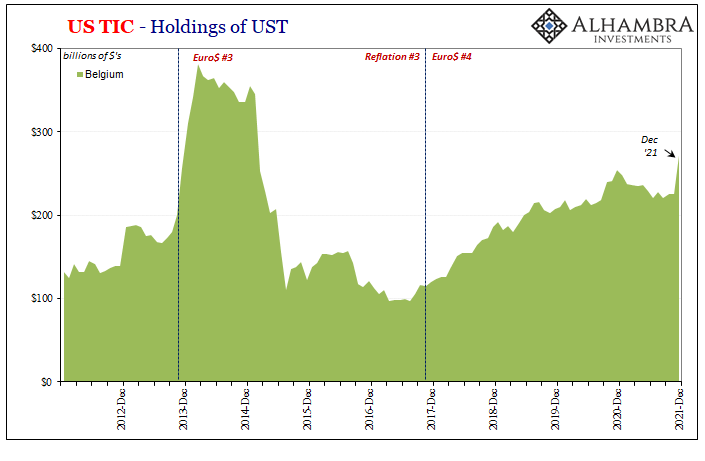

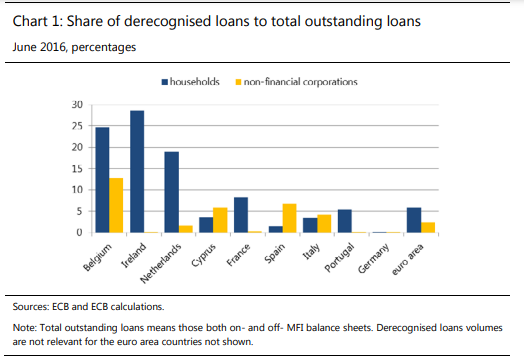

First of all, December 2021 already gave us a collateral surprise in Europe. Belgium. Almost fifty billion in USTs. So, what might Belgium have to do with derecognized European NFC lending? Not surprisingly, because of Euroclear’s location, Belgium is and has been one of the three primary jurisdictions where banks securitize NFC loans (and household loans, too) creating this data adjusting need from all the derecognized assets being derecognized in those three places.

So, what might Belgium have to do with derecognized European NFC lending? Not surprisingly, because of Euroclear’s location, Belgium is and has been one of the three primary jurisdictions where banks securitize NFC loans (and household loans, too) creating this data adjusting need from all the derecognized assets being derecognized in those three places.

Surprise, surprise, Belgium is the biggest reason for it and by far the most in NFC securitizations:

I couldn’t find any updated figures beyond 2016 because, well, who actually cares about derecognized European NFC loans that might be used to work around systemic collateral scarcity ongoing for nearly fifteen years?

So, a huge rush of USTs flow in to Euroclear during December, and then in January a massive drop in at least the ECB’s adjustment factor for derecognized loans which is kind of consistent as if European banks maybe didn’t need as much collateralized ECB funding.

Obviously, the numbers don’t match ($46 billion inflows of USTs versus -€150 billion ECB factor) nor does the currency denomination. The latter doesn’t necessarily matter as much as you might think since swapping currencies isn’t all that difficult, especially when you suddenly have pristine USTs to back up whatever transaction starting from US$s.

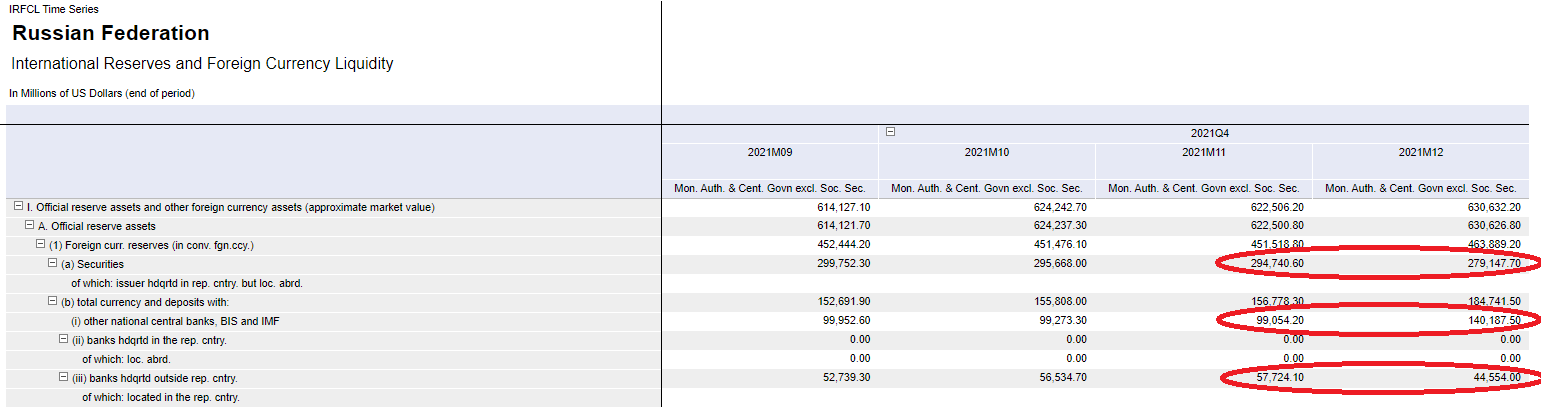

If this was all I had to draw assumptions from, though, I wouldn’t be writing about it. But, something else big happened two months ago, too:

And already in December 2021, the Russians, apparently, liquidated $15 billion of [securities] seemingly out of nowhere. In fact, using the IMF data, they have been shifting tens of billions out from securities and into liquid deposits with other central banks and governments (maybe the BIS; we don’t have that level of detail), while drawing down nearly $10 billion from those private banks.

The balance with foreign officials had been bumped up by almost $50 billion since last February, with $40 billion of that in December alone.

The Russian government via its central bank and whatever other official channels has been radically changing the liquidity profile of its reserves. It began doing so in March 2021, not a random fluke given that Vladimir Putin had ordered troops to mass on Ukraine’s borders beginning in that same month.

Did the Russians liquidate about fifteen billion in securities during December alone? We know they weren’t USTs, because Russia was forced out of those way back in the middle of 2018. Could they have been swapped? If so, would that have required a deposit into, say, Euroclear during December?

And if whatever Russia was holding as securities had been swapped into some number of USTs, then deposited into Belgium, these then used as collateral for those liquid assets/deposits noted above, Russia ended up with the most liquid form of reserves, its hands on US$s, without having to report much beside the end results.

Just in time for the February invasion.

What we find in January ECB lending/collateral/derecognition might be partially the downstream consequences of these maneuvers.

To close, let me again reiterate that this last section is pure speculation for the purposes of forming ideas and theories with the intent to validate, or invalidate, them by events and data as each develops in the near future. And, to be clear, I’m still far from convinced the Belgium USTs are not China’s (certainly some of China’s).

What we do know is something’s going on money/collateral-wise throughout Europe simultaneous to the buildup toward Ukraine.

We also do know, via the IMF data on Russia’s holdings, Putin wasn’t standing still in monetary terms leading up to what was certainly his intentions all along. It’s at least something to keep in mind while considering the potential (versus advertised) effects from any future sanctions, including delinking Russian banks or maybe even its central bank from SWIFT (a messaging system, not a clearing nor settlement system).

More on Russia, its gold holdings, and SWIFT tomorrow.

Re: SWIFT & sanctions.

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) February 26, 2022

People seem to have the wrong idea about what it is and more importantly who controls it.

We've been on a eurodollar NOT DOLLAR standard for half a century. Eurodollar not dollar.

This is a categoric difference. https://t.co/16SCVrKVcj

Stay In Touch