At some point, these are just numbers. By themselves, numbers give you no context, nor any sense of bearings. Arithmetic merely lines everything up and counts what goes where. To a top-down central economic planning structure, everything is as if a spreadsheet; if X, then Y.

But then what?

China’s 13th National People’s Congress jumped into its fifth annual session this past weekend, which means plenty of politics to go along with the window dressing. This is the gathering which schedules fiscal and economic issues being made public, each long predetermined inside the restricted halls of the Chinese Communist Party power structure.

Already Premier Li Keqiang has said that “stability” will be the government’s main focus. To make sure everyone heard him – whatever the Chinese word for it – Li repeated the term numerous times throughout his report to the Congress.

In our work this year, we must make economic stability our top priority and pursue progress while ensuring stability.

Why stability? Why not legit expansion and recovery? After all, what’s said outside the country is that the Chinese have done it right and will lead the world into a post-COVID era of reborn prosperity. Or maybe just inflation. Either way, a great burst of activity to continue forward.

Yet, Li has stated numerous times since 2019 how “downward pressure” is China’s most prominent economic (therefore political) feature. Contrary to what’s discounted as all but certain vigor in outside mainstream media sources, there’s an enormous struggle just to keep the economy in its low and diminishing range.

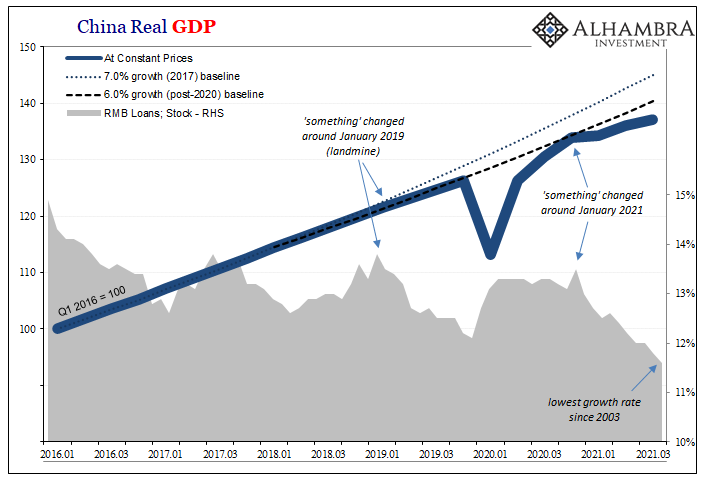

Authorities had already announced a 2022 goal for real GDP: about 5.5%. Not long ago, 7% was considered a Chinese recession. Back in 2009, China’s brief, temporary flirt with 8% was regarded as consistent with the rest of the world then undergoing its Great “Recession.”

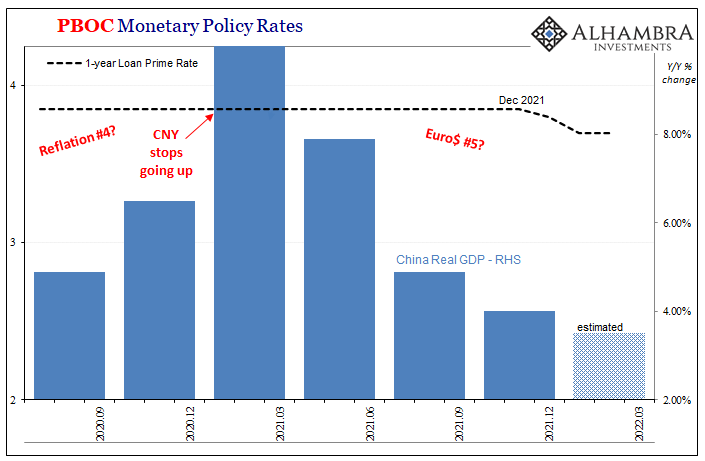

Given the threats still emerging, even in Western circles there’s unusual skepticism as to Beijing’s ability to generate even 5% this year. To that end, at the end of 2021 the PBOC was moving contrary to the Federal Reserve by lowering several benchmark rates.

It is almost certain to do so again in the coming months; Li practically admitted that China’s banks are being “encouraged” perhaps “urged” to further reduce credit rates particularly to small and medium-sized businesses (as if China has turned European now). The five largest “commercial” banks (they may be commercial banks, but they are not privately owned) have been told to up their lending volumes to these smaller companies by 40% in 2022.

Sounds huge, doesn’t it? The Chinese cavalry finally running to the global economy’s rescue as last year’s “growth scare” has only disappeared from the Western media in the latter’s fixation as if Russian and Ukraine are the world’s only sore spot at the moment. After all, credit skyrocketing by 40% in this very crucial macro bucket on the say-so of China’s top echelon, guaranteed to have been approved by Xi, this must be an economic gamechanger.

Except, no. The Big Five commercial banks had already reported that last year, on the government’s “urging”, they had together expanded credit to small and medium businesses by about…30%. China’s CCP simply added another 10 to the target when adding one to the calendar year.

What good did that 30 do for 2021, and what more might a 40 accomplish in 2022? All just a bunch of numbers arbitrarily plucked out of the sky, as is standard control procedure.

The fact that these figures are going slightly higher tells the tale of increasing woe; why Li Keqiang has been given the duty (as nominal Number Two) to speak more and more about stability in the face of downward pressures. Bigger targets don’t mean anything other than admitting to greater for those.

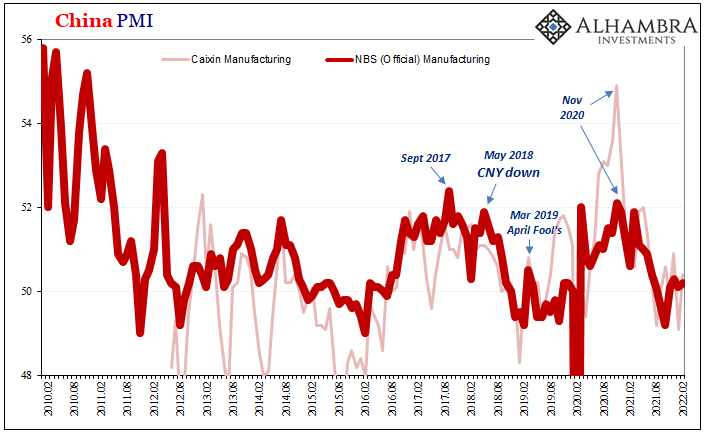

With the calendar having turned March, and China’s Golden Week seasonality behind, the data for the start of 2022 will begin filtering in. They’ve produced PMIs already for both January and February (the latter released last Monday), each one still grim.

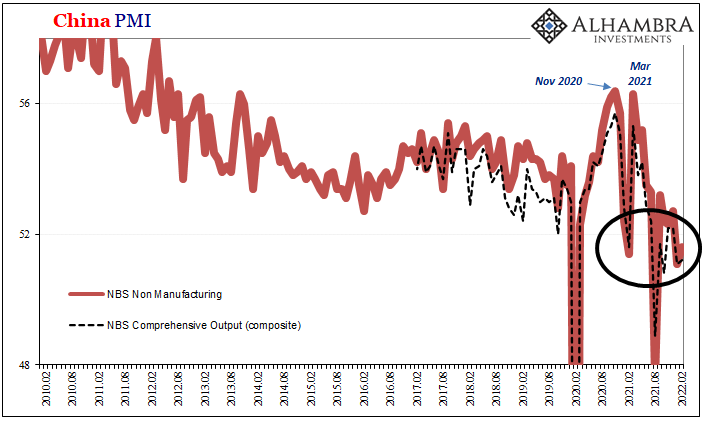

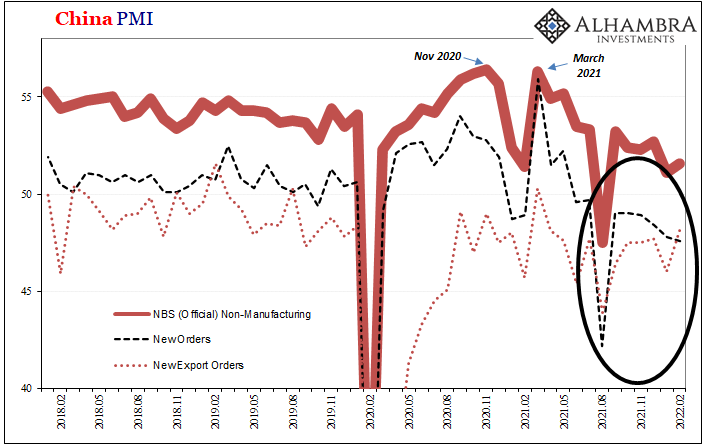

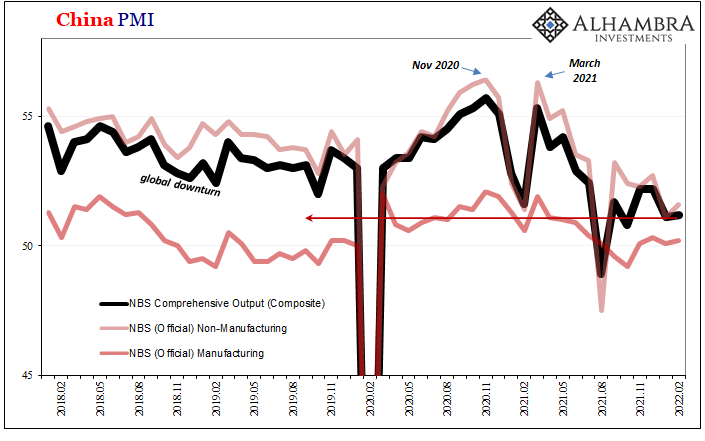

Low headline and component levels had been blamed – in the West, anyway – on omicron’s effects in January. Yet, for February, only the smallest rebounds: China’s NBS said manufacturing went from 50.1 to begin this year to 50.2 last month; the non-manufacturing headline PMI rebounded from an alarming low of 51.1 for January to just 51.6 February.

As for the latter, non-manufacturing, new orders (domestic) declined further to 47.6 from 47.8, while export orders improved to just 48.1 in February from a ridiculous low of 46.0 in January.

The NBS estimate for its composite output barely moved, up to 51.2 last month from 51.1 the month before. Any chart for either sector (including Caixin’s sentiment estimates) sure does look like “downward pressures” remained if not accelerated to the downside despite last year’s 30% credit growth from big banks to small and medium businesses.

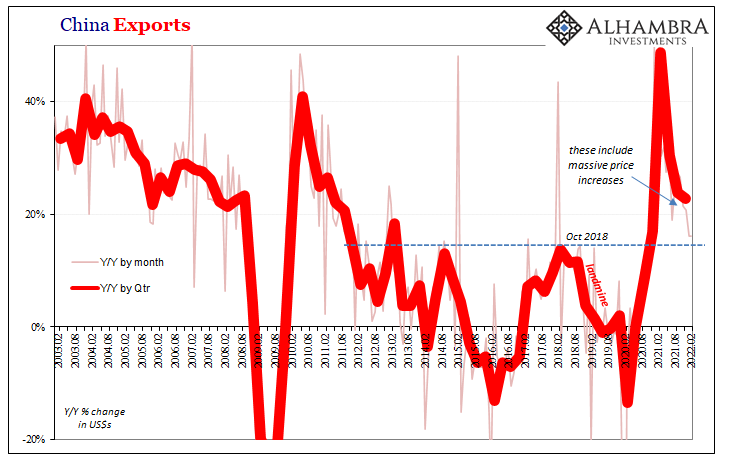

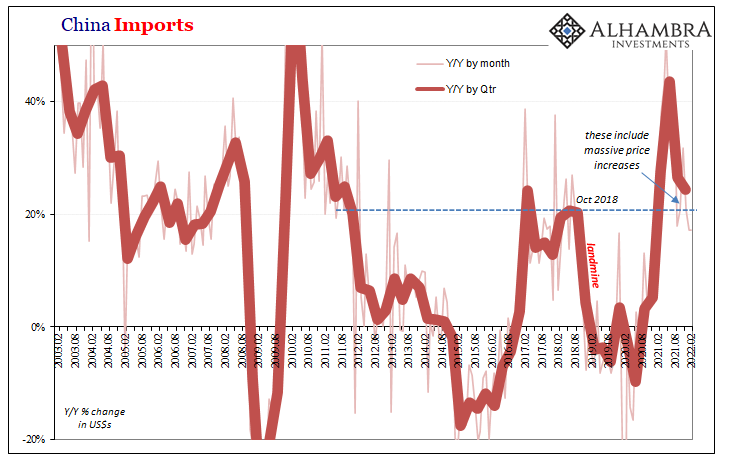

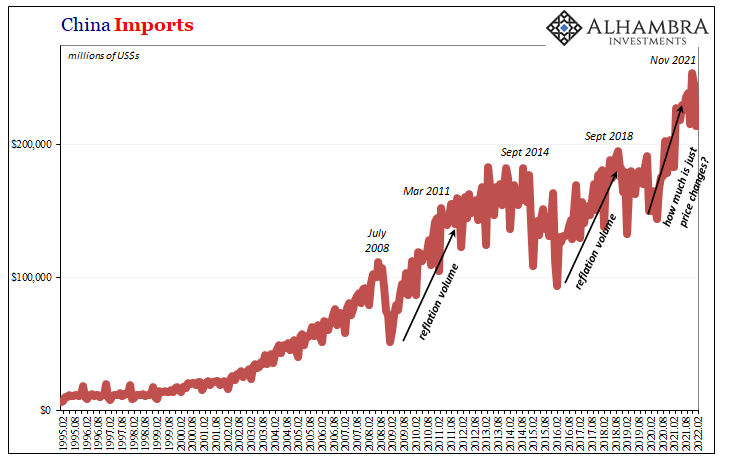

Transmission from China to the rest of the world, or the rest of the world through China, takes place in global trade. Last night (early today Chinese time), the country’s General Administration of Customs said exports increased (January-February combined) 16.3% year-over-year (in US$ terms), while imports rose 15.5%.

Each was the lowest growth rate for their respective classifications since 2020 (though modest base effects are at work here). Regardless of the math, the trend seems relatively clear, both official word and economic action. PMI’s and sentiment, to go along with actual trade figures.

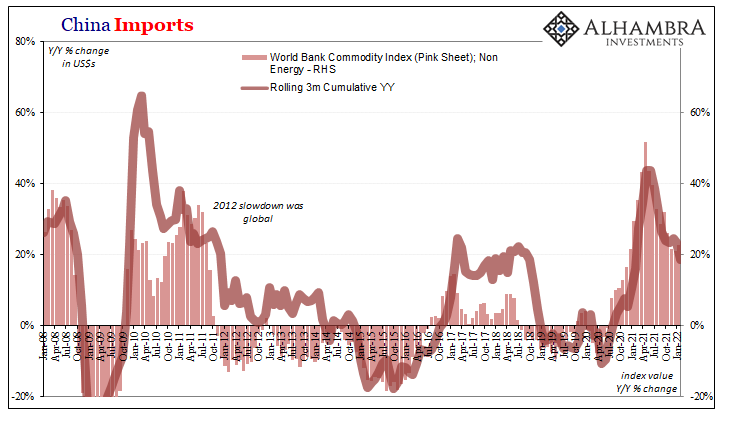

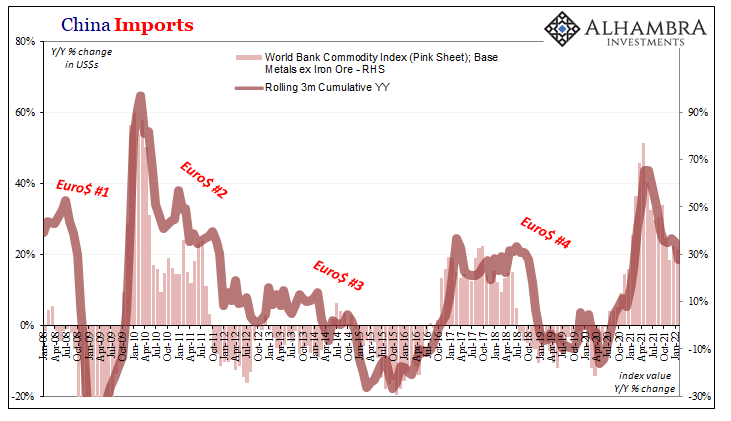

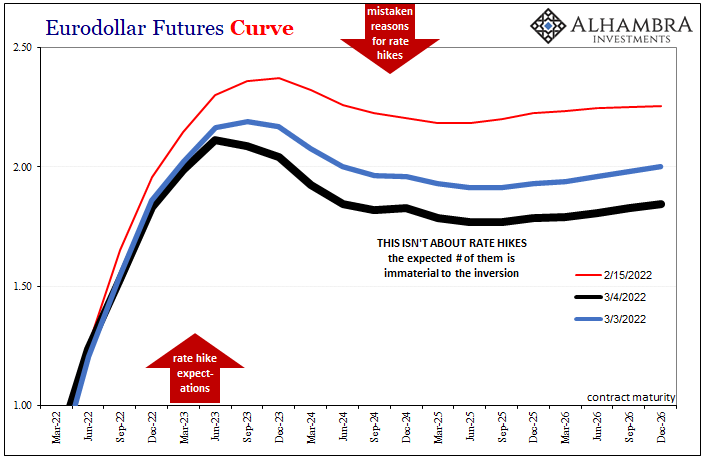

And that is before taking into account last year’s huge foible – the price illusion and its impact on commentary and perception. While China’s trade numbers are now slowed back in range of their 2018 levels, rates of increase that led the world toward a 2019 downturn and global recession, in terms of volume these must be significantly worse today (the Chinese GAC, unlike the US Census Bureau or Japan’s Customs, doesn’t estimate aggregated price effects).

In other words, the Jan-February 2022 y/y increase in imports was, again, 15.5%, slightly less than October 2018’s 18.4%. Yet, the current 15.5% is hopped way up on price increases whereas October 2018’s were much smaller. This can only mean that physical imports have already decelerated to very low levels, probably more alike December 2018’s +4.4% if not already negative in the way imports sank from the start of 2019.

Taking account of the price illusion and putting it together with either form of macro sentiment, manufacturing and not-manufacturing, Li Keqiang’s message to the rest of the world isn’t, Yay 40% credit growth!

Rather, it is more emphasis on “downside pressures” which continue unabated therefore require some kind of further stabilizing the Communists are hoping another 10 on top of last year’s 30 just might keep China from a more disorderly slide even further downward.

In managed decline, the direction as the destination is all but guaranteed here. The true central planning emphasis insofar as China’s authorities are concerned is only how China might be able to get there.

Stay In Touch