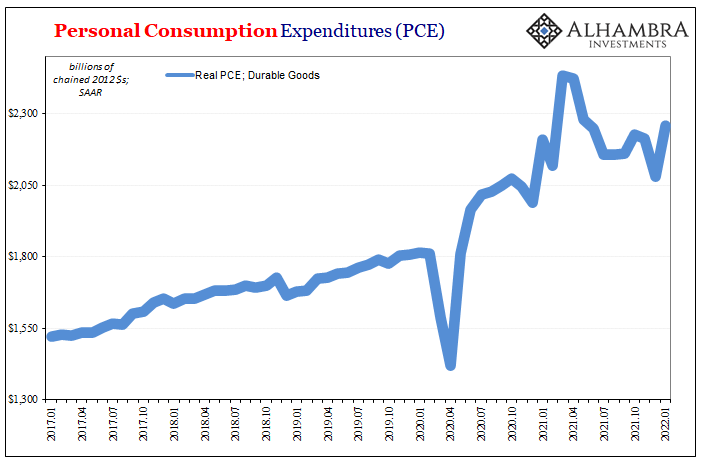

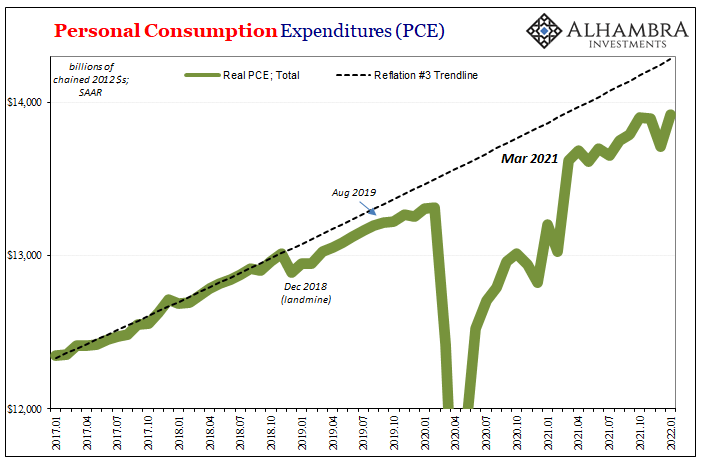

We’ve seen the combination of last year’s over-ordering together with some improvement in the transportation of goods become this year’s record surge (some of this prices) for inventories. Across the supply chain, retailers have been hit with the most recently but there’s been excessive builds for wholesalers, too, along with manufacturers.

This potential problem compounds if or when consumer sales soften simultaneously. Should consumers hold up their end and keep spending furiously, the goods economy could work its way through even a monster accumulation like this.

Cyclical stuff.

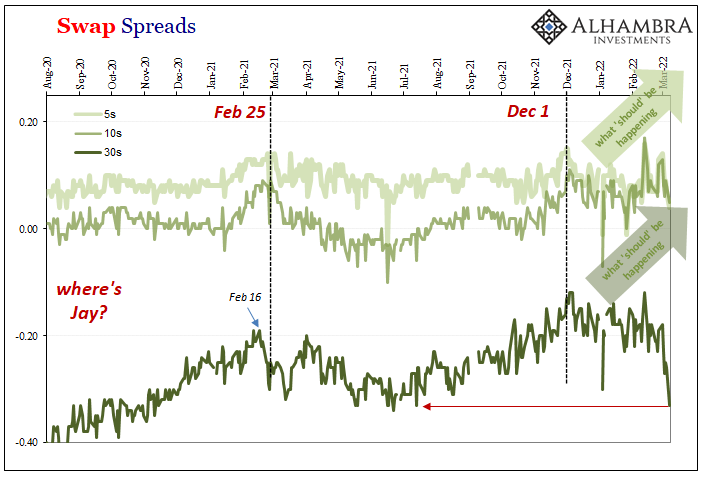

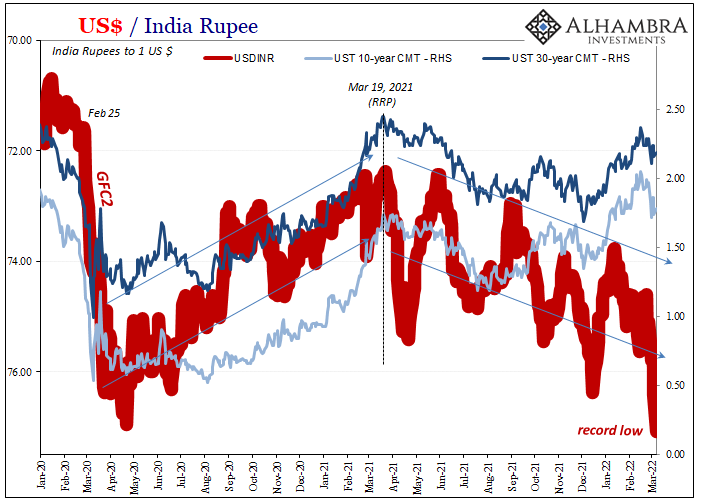

As the yield curve drops, is it all pessimism on Russia/Ukraine?

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) March 1, 2022

A lot, sure, but not all. Cyclical indications are everywhere, too. pic.twitter.com/ufAwTb85MS

While overall topline sales have stayed robust, there are incremental warning signs as to whether this will or even can continue much longer. If not, then the inventory cycle kicks in, a huge problem for any economy let alone this one where goods has been the sole bright spot (creating the impression of a system overheating when the hotness has actually been contained to the one sector).

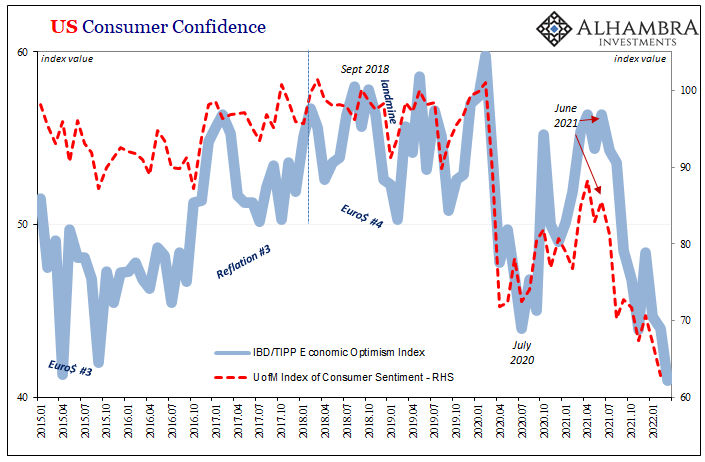

Let’s start by reviewing the latest data on consumer confidence. Wishy-washy sentiment, I know, yet of some value when big changes in it show up. According to Investors Business Daily’s poll on economic optimism, big changes have shown up.

The IBD/TIPP poll has been among the more consistently optimistic, too, which makes its late 2021 breakdown all the more compelling. The above-50 readings, for example, kept up throughout the US’s 2018 spiral into 2019 downturn maybe recession. Not only that, this one matches pretty well with what the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers has uncovered, too.

First to give us a number on March 2022, IBD/TIPP contains some sobering values:

The IBD/TIPP Economic Optimism Index, an early monthly read on consumer confidence, slid 3 points to 41, the lowest since October 2013. That makes seven straight months below the neutral 50 level. Readings above 50 reflect optimism.

As bad as that sounds, the underlying details look even worse.

The data provider reports that 6-month forward expectations for the economy are the lowest since August 2011. Being compared last with the maelstrom surrounding the eruption of Euro$ #2 is never going to be a good thing.

Oil and gasoline prices are doing much of the damage here, obviously, but I’ll submit that general pessimism found by these polls isn’t only “inflation.” Rather, there are indications of softening all over the place, including, perhaps, the labor market.

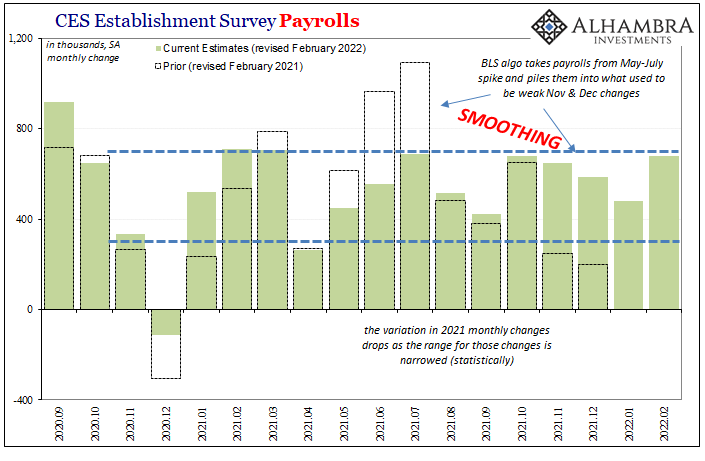

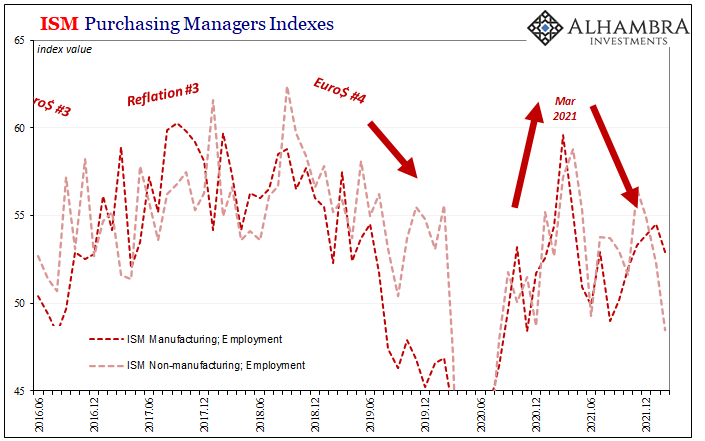

Though the major government payroll reports may be (overly) smoothed (taken to the nth degree by private ADP), outside estimates such as those provided by the ISM (last week) are hinting at what the BLS numbers used to look like before those gross statistical processes were put to work. The employment subindex for both the ISM’s Manufacturing and Non-manufacturing surveys haven’t just gone down, they’ve stayed suspiciously low even since last year’s transition.

And for the latter, non-manufacturing, net hiring is thought to be down for the first time since December 2020, and the lowest since Summer 2020.

Blamed, of course, on the labor shortage theory, might consumers have grown increasingly dour due to the higher costs of living at the same time as the last of economic reopening hasn’t been quite as robust as so far billed? If you are uncertain, at best, about prospects for employment at the same time as gasoline surges, that’s surefire pessimism.

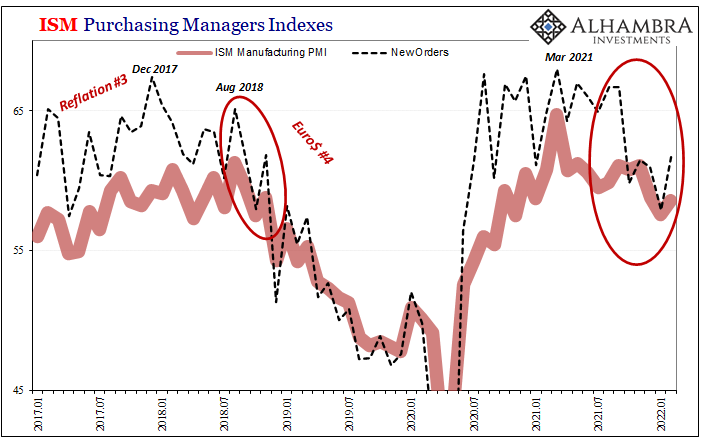

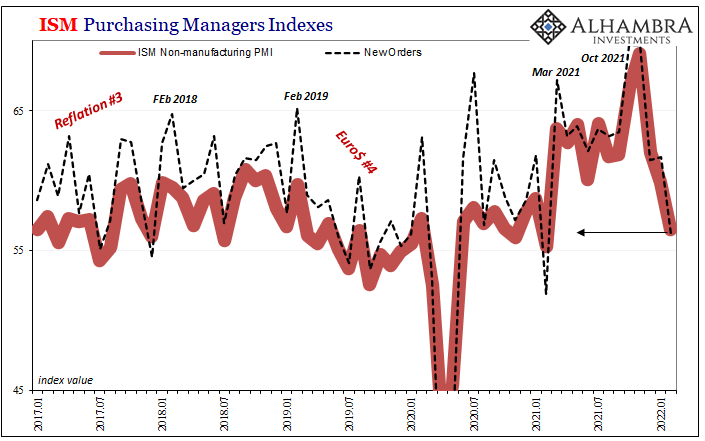

Even above each’s employment components, headline ISM numbers – the non-manufacturing, in particular – point to last year’s second half “growth scare” at least continuing on into the first couple months of 2022; just in time for the latest leg higher in WTI crude.

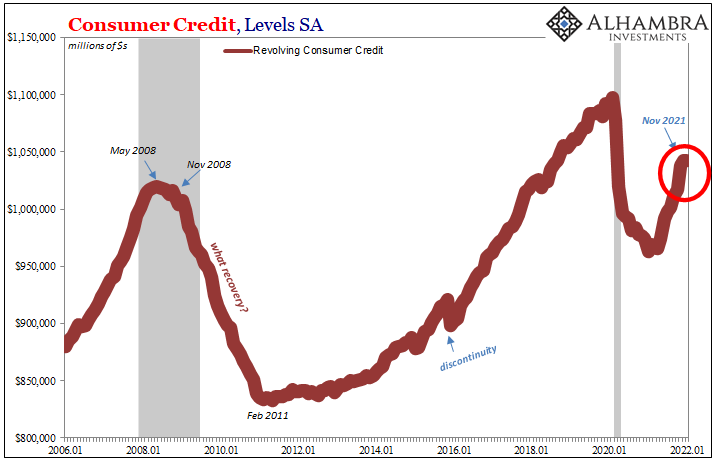

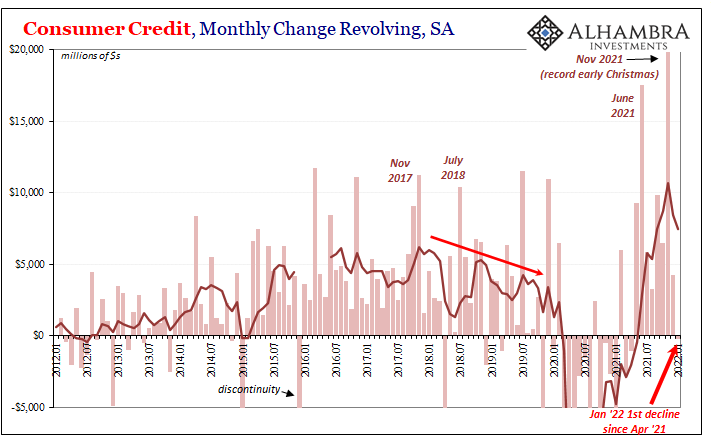

A more direct and immediate window into consumer behavior, actual activity, may have must been provided today by the Federal Reserve. I’ve looked at consumer credit, especially revolving credit balances, as a proxy for, essentially, consumer confidence.

When revolving balances decline, that almost certainly means the wealthier or better off credit card holders are paying down their balances as a measure of prudence. This was very clear in 2008 and again in 2020.

According to the latest credit estimates for January 2022, total revolving credit (seasonally-adjusted) was thought to be slightly less than it had been in December. It was the first monthly negative since last April, after November had been the greatest positive single-month change on record.

Consumer hangover after early Christmas shopping? Maybe omicron effect in certain states, but disease-averse staying home had before led to more buying online rather than less, much fueled during last year’s delta wave by credit card usage (June-August 2021).

One month certainly doesn’t make a trend, and the data itself is noisy and subject to, at times, large revisions. In the context of potential consumer spending patterns, however, that small decline in revolving (on top of a much smaller than expected increase in non-revolving credit during the same month) does nothing to refute the interpretation(s) of the other data presented above .

This is one to watch should it develop further along the lines of published confidence and other kinds of affected sentiment.

Put the potential of all these things together with the demand destruction possibilities represented by record high gasoline prices (more supply shock), and widespread, uniform financial market pessimism is at least as understandable as what’s being indicated from consumers. After all, most of them take their economic cues from the stock market (just as Jay Powell’s Fed expects and seeks).

Stay In Touch