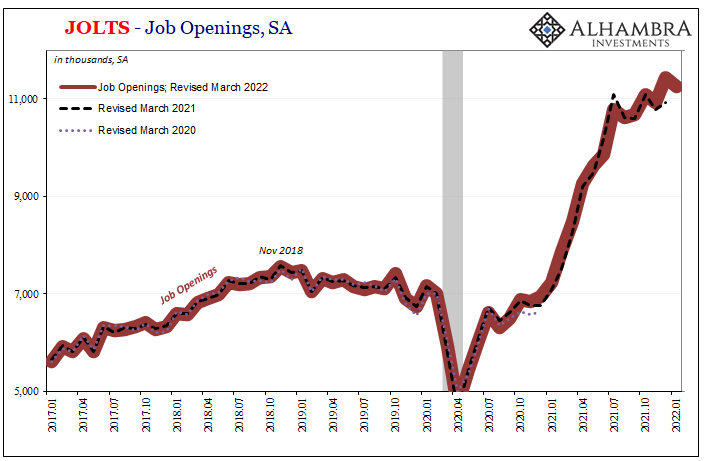

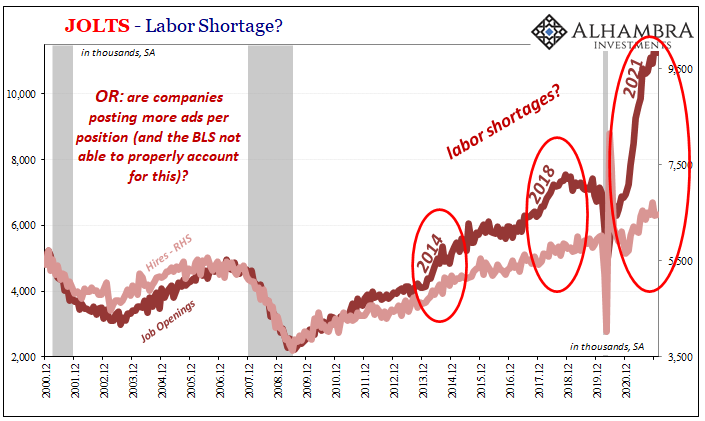

Benchmark revisions have visited the BLS JOLTS survey, too. And yes, they’ve been smoothed. To that end, the hawkishly-watched Job Openings (JO) trend has been altered. Before this week’s release, JO had peaked like the Establishment Survey back last summer and had seemed to soften since. Now, JO continues on an upward bend rather than downward.

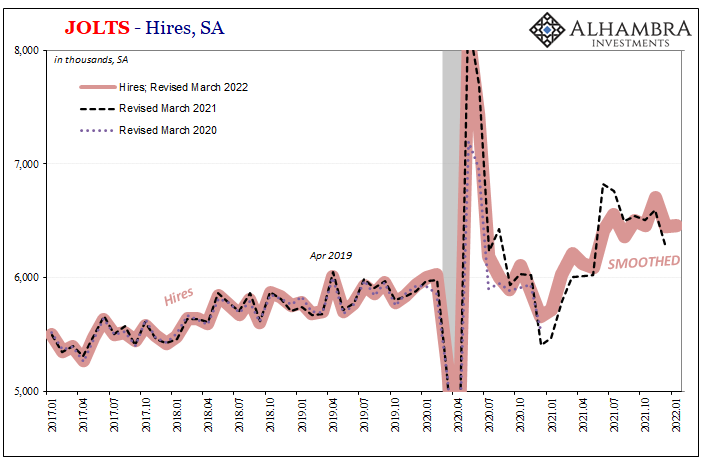

For JOLTS Hires (HI), the revisions are more dramatic in that they now very closely (as is designed) match the new (though improved?) estimates for headline payrolls (CES). The government has taken the liberty to exercise its smoothening touch over here, too.

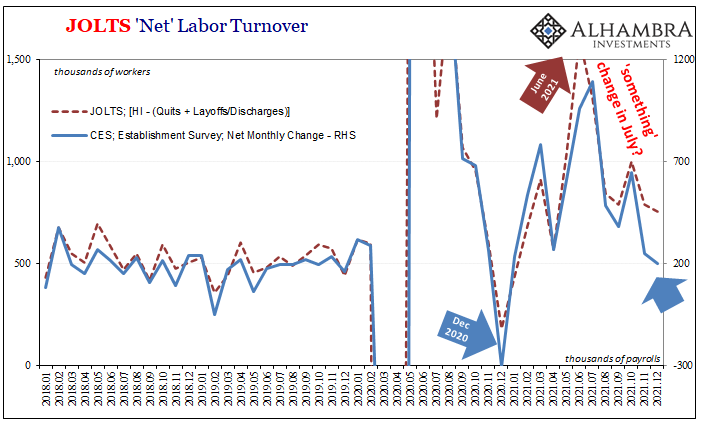

The more noticeable, and noteworthy, impact of these revisions is how neatly they have solved the discrepancy, make that prior discrepancy, between JOLTS total turnover and payrolls. Before last year’s data under the previous benchmark, netting monthly turnover essentially equaled the month-to-month change for the Establishment Survey.

The two had gotten out of alignment, however, during the back half of last year which seemed like there were too many quits, too few hires on the turnover side, and just fewer payrolls to have been added for CES.

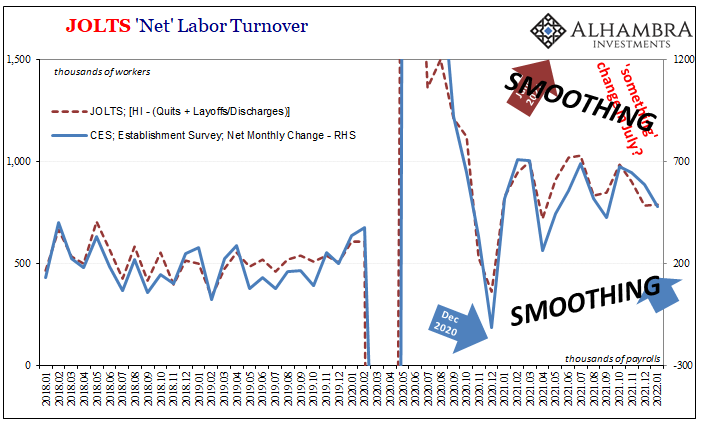

Again, as is designed, under the revised benchmarks there today isn’t a spot of substantial difference left; all cleaned up, everything very well smoothed out. I’ve included last month’s chart using the old benchmarks below so you can see how the prior series had diverged, and then left all the arrows included with the updated figures so to more clearly illustrate the effects of the revisions.

Whereas the labor market seemed to be softening over the last half of last year from a very high 2021 reopening high, today there’s nary a variance in the trend. Just smooth sailing in net turnover like payrolls ever since last January’s pickup.

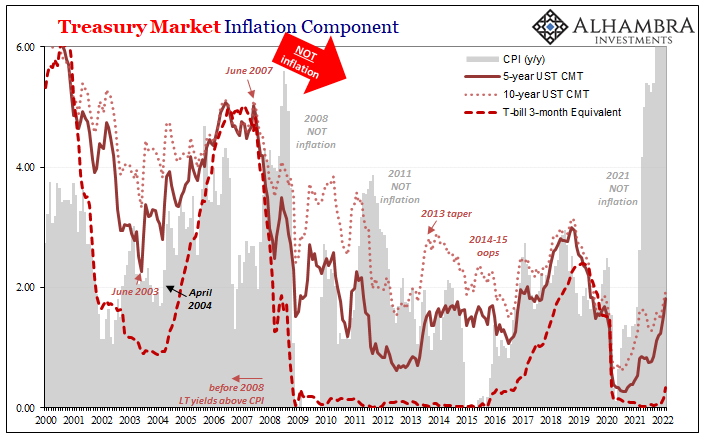

This gets thrown in with the other few of the Fed’s hawkish ammunition, though none is necessary. The FOMC will begin raising its policy targets and toolkit rates regardless, starting with political reasons (APPEAR TO BE DOING SOMETHING ABOUT OIL PRICES!!!) before then transforming CPI expectations into a combination of the unemployment rate and job openings.

But what about the real economy itself? Is some prudent action warranted?

Maybe rate hikes can’t somehow make America pump more oil or get farmers across the vast Midwest grow more wheat to make up for what won’t be harvested in Ukraine, there still might be an employment argument, a theoretical one, for what this labor data represents about Americans greeting full employment.

And that begins with the presumed demand for labor, as stated by sky-high JO. According to the latest estimates cobbled together from the updated benchmark, there remains a huge, yawning chasm between JO and HI when there should be no distance whatsoever between them.

For most, because of the monolithic mainstream view, this is nothing other than the widely-reported labor shortage. Companies desperately want workers, thus JO in the stratosphere, but they can’t seem to find enough of them, therefore HI far less.

Prominent among the anecdotal examples of this, and pertinent to the prices for all manner of goods in the CPI, truckers. No one can seem to get enough drivers to haul the mountains of goods, a desperate scarcity that The Washington Post tells us is a real threat to our “prosperous economy.”

You’ll note, if not because I’ve already circled it, this “severe trucker shortage” dates to June 2018 rather than June 2021. And that only raises the same questions for today as went unanswered back then.

I asked those just a few days after the article had been published, and they still need to be answered both for what happened almost four years ago (rather, what didn’t happen) as well as what we should expect out of 2022 where smoothed labor market numbers might not help.

In all likelihood, there is a shortage of truck drivers. That much we can probably all agree on, but it remains an anecdote of one specific industry that doesn’t add up to the increasingly worrisome income data. As noted before when tackling this same topic for the nth time over the last few years as the unemployment rate fell, the question in any business is not “do you pay a lot?”, rather it’s “do you pay enough?”

That’s the thing; there probably wasn’t an adequate supply of rig operators to haul goods in the middle of 2018 just like there surely aren’t nearly enough today. But why? Four years (and it really goes back farther in time) and we’re still so short truckers.

While pay for being a driver is relatively high compared to a lot of other jobs, trucking firms obviously haven’t offered to pay enough. There really is no other answer to what truly isn’t a puzzle (or some unsolvable paradox).

Companies may indeed be posting massive numbers of job openings across the whole economy in reality like the BLS data makes it appear, but they clearly still aren’t paying the market clearing wage right now which had already been a serious and consistent problem long before the 2020 recession. The mainstream view will view this as a “labor shortage” regardless of the correct economics (small “e”).

Like so many other things, you don’t have to take my word for it, either. New polling data released this week provided a straightforward answer. Having actually asked the quitters who quit during last year’s so-called Great Resignation just why they had, you’ve probably already correctly guessed what most said was behind their reasoning.

A new Pew Research Center survey finds that low pay, a lack of opportunities for advancement and feeling disrespected at work are the top reasons why Americans quit their jobs last year. The survey also finds that those who quit and are now employed elsewhere are more likely than not to say their current job has better pay…

Almost two-thirds, 63%, cited crap (my word) wages and lack of advancement opportunities (crappy next stage wages) as either their primary or a minor reason for quitting.

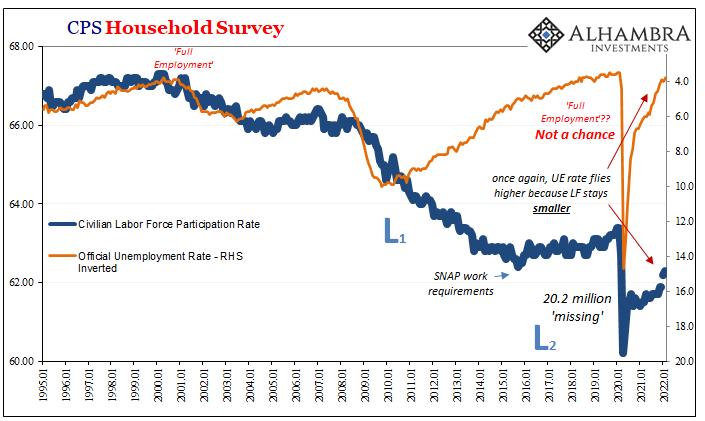

If that’s what it was for those previously employed, we need not imagine what the pay must be offered for those who aren’t and choose not to join the labor market. Rather than a labor shortage as advertised (pun intended), a recovery shortage whose ultimate extent is not limited to the COVID era.

This has been a huge issue, the primary issue going back to when the labor force first took its wrong turn – back in October 2008.

Companies aren’t hiring at the rate the economy needs because they won’t commit to the market-clearing wage. The economy never once recovered sufficiently following the Great “Recession” and is now repeating the same downside process despite those lofty labor numbers more to do with pandemic reopening than actual, legitimate “booming.”

Prosperity? We’re nowhere close and thus Jay Powell is yet again, for the second straight time, about to commit to rate hikes for all the wrong reasons.

The markets all know it. We aren’t going to smooth-talk ourselves into full employment.

Stay In Touch