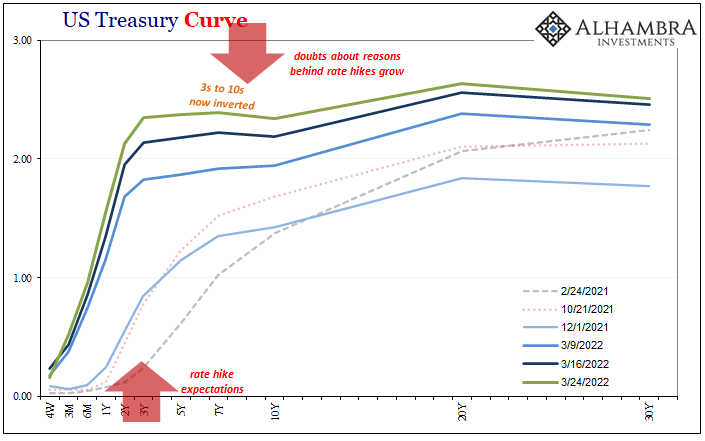

What can we make of the fact the US Treasury yield curve inverted between the 7-year and 10-year maturities first? It only took a few more days for more of the curve to bend upside-down, yet that just means the whole middle part is where the bad vibes are congregated. Does this somehow disqualify what would otherwise be a clear message?

Policymakers like Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell would like you to believe it does.

Right on cue, here come the denials: "Pay no attention to that thing that always makes us look bad because it always ends up being right. This time, THIS TIME, we got it!"

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) March 22, 2022

We just did this three years ago. And who could forget 2007 (or '00).https://t.co/pjJw34yf0S pic.twitter.com/OKw0tc3FdH

After announcing an aggressive expectation for rate hikes to combat what he says are far more pronounced inflation risks, combined with that obvious curve inversion for Treasuries, naturally there were a few questions about recession since inversion and contraction historically go hand-in-hand. The Fed’s top man was asked about it at last week’s rate-hike announcing press conference.

CHAIR POWELL. So I guess I would start by saying that, in my view, the probability of a recession within the next year is not particularly elevated. And why do I say that? Aggregate demand is currently strong, and most forecasters expect it to remain so.

He then listed all the usual stuff, payrolls, strong household balance sheets, etc. Yet, he was asked a second time about recession a little bit later on, to which once more Powell referred back to his interpretation of economic data. To try to emphasize his point, the Chairman made the claim that “forecasters” agree with this view as if that somehow had decided the question once and for all.

CHAIR POWELL. Well, I — you know, I say that our intention is to bring inflation back down to 2 percent while still sustaining a strong labor market and that the economy is very strong. If you look at where forecasts are, you — people are forecasting growth that’s strong within the context of US potential economic output.

He said this even though other questioners had already pointed out how the Fed’s very own models had just downgraded US real GDP expectations for CY2022 to just 2.8% from 4.0% in the December projections. Undeterred, Powell repeatedly insinuated if forecasters say it’s all great, then pity those who don’t agree.

Just who are these forecasters?

They are other Economists who model the economy in the exact same way – using the exact same kinds of econometric models – as the Federal Reserve. Circular logic.

Sensing he needed to at least address the inverted elephant in the room, Powell also claimed, “…we look at a broad range of financial conditions…It’s not any particular financial condition but a broad range of financial conditions, they will reflect to some extent — they reflect any number of things.” How Greenspan-ish; therefore telling.

His message: don’t focus on the long end of the yield curve and don’t get caught up in its inversion. Economists are confident that the curve is doing crazy things for crazy reasons, and that in the end none of that craziness will matter.

Of course, history shows us that the middle curve inversion has indeed been a solid indicator of both recession (pre-crisis) as well as serious global distress (post-crisis). In fact, it has been the 7-year to 10-year calendar spread which has been among the best of the earliest warnings.

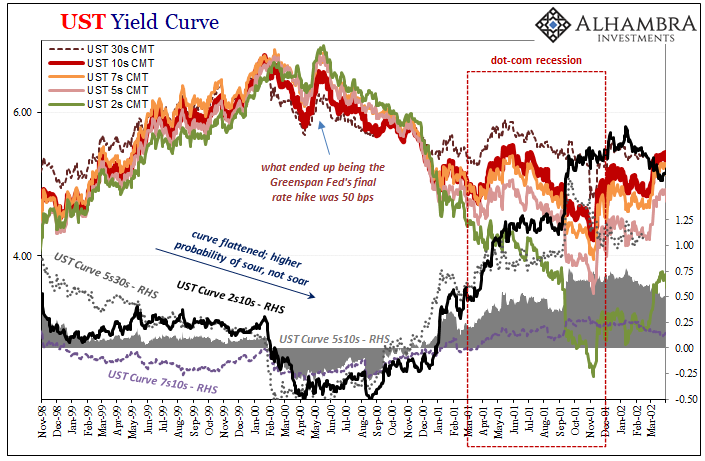

Go back to the period before the dot-com recession, and the 7s10s was first (and most consistent) to doubt the Greenspan late-nineties inflation-scare. That earlier FOMC, absolutely convinced about high inflation risks (even after the stock market had peaked), egged on by “forecasters”, kept on hiking rates though the long end (not the short end) UST curve kept up pricing the opposite case.

The 7s10s had inverted back in late ’98, meaning the whole rate hike cycle from June ’99 to May ’00, the bond market itself “forecast” increasing potential risks that weren’t inflationary. Late January ‘00, the rest of the long-end curve would only add to the contrary case.

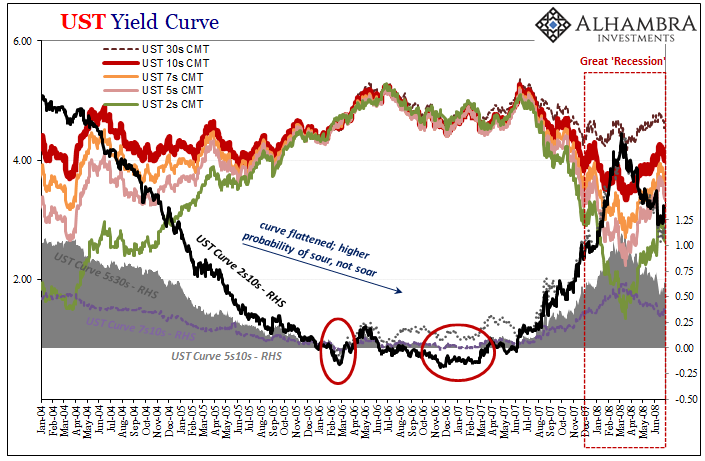

In the middle 2000’s, those longer spreads went upside down mostly together at the same time forewarning (again, despite the Fed and Greenspan’s “conundrum” made more confusing by equally confused professional forecasters) of what became the Great “Recession.”

But do these examples let Powell off the hook if on a technicality?

By the pair of cases shown above, it might seem long-end inversion(s) signals trouble a long way ahead, down the road a year at the earliest if not two. Is the yield curve just looking too far beyond Powell and his forecaster friends’ shorter horizon?

Perhaps, but we also have to consider other cases – particularly those far more recent.

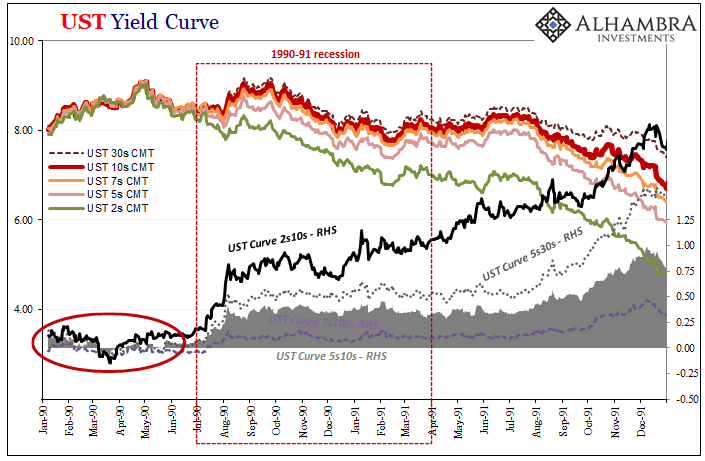

First, though, the incident before the 1990-91 recession:

Again, 7s10s go first, the rest of the long-end curve joins pretty quickly thereafter and then recession arrived within a matter of months, not years.

And there were all sorts of banking and monetary irregularities which sped up the process, too, including the S&L Crisis escalating toward a climax before then an oil price shock contributing the final blow (crude prices had risen sharply in those very same months before Saddam’s August ’90 invasion, too).

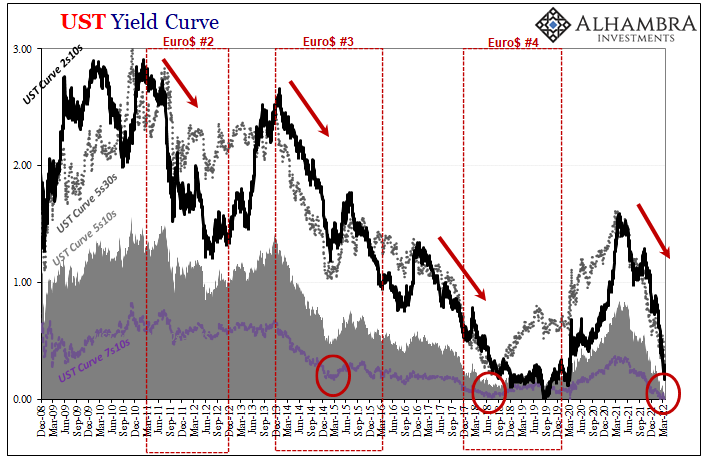

Moving forward to the post-2008 world, while the long parts of the yield curve wouldn’t invert until August 2019, even before during the prior up and down reflation cycles, other segments like the 7s10s we’re focused on here were among the more obvious – and timely – to indicate the downside in each case.

In early 2015, major flattening left very little time before the near recession in the US (major depression outside too many other places around the world) hit just months after (though the curve would not invert at any place).

That same would repeat, to an even more obvious extent, in the middle part of 2018 when the 7s10s came with a whisker, just two and three bps of overturning right in the thick of the collateral days (around May 2018) and then again when eurodollar futures would go full-blown inverted (mid-June).

Like the Euro$ #3 cycle, the US downturn from Euro$ #4 would also slam into it in mere months, not years.

Now today in 2022, despite what Jay Powell claims, not only did the 7s10s already upturn, the rest of the middle curve very quickly followed.

It is absolutely true that Economist forecasters expect the economy to remain as it is “currently strong”, but by every reasonable and honest interpretation of a broad but useful set of indicators, only starting with the long end of the yield curve, recession risks would appear to be, indeed, quite elevated.

At least some in the mainstream seem reluctant to follow the Fed off a cliff (again).

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) March 23, 2022

Most will anyway because they don't know any better. That's how bad Economics has been at alerting/educating the public.

Don't Fight The Fed? Get out of here.https://t.co/5YBRUMhhmq pic.twitter.com/esLYrqna42

Stay In Touch