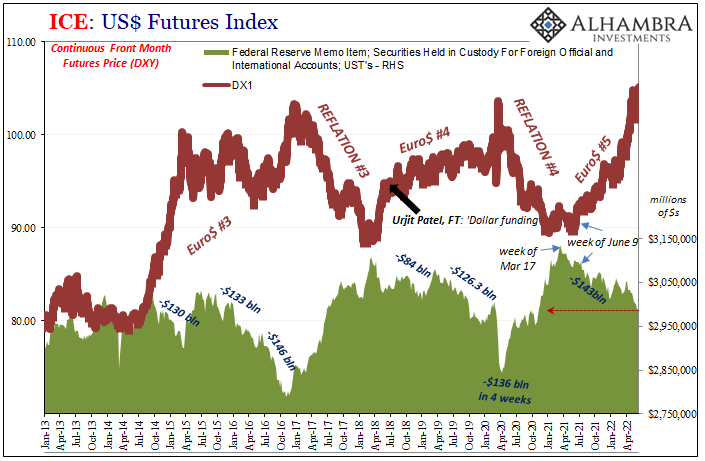

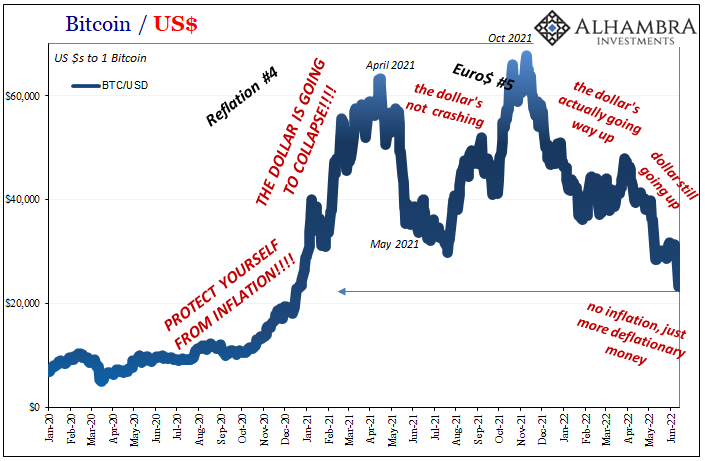

It takes time even for a powerful eruption of deflationary money to get sorted into the real economy. Nothing goes in a straight line and even big changes don’t just happen right away. The last time, Euro$ #4, it began early in 2018 triggering all kinds of financial disruptions and monetary fireworks. The same familiar indications, rising dollar, flattening and inverted curves, collateral, you name it. What we see today.

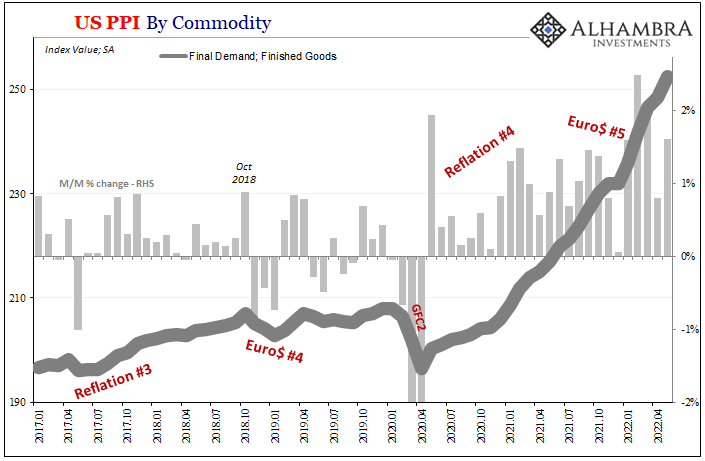

But while all that was going down, consumer and producer prices in the US kept going up. Of those latter, the US PPI, it wouldn’t actually reach its peak until November and December 2018, deep into that landmine almost a full year after Euro$ #3 had first struck.

There are substantial disparities this time compared to that one, yet these are mostly matters of degree rather than categorical differences. The one which isn’t is oil/gasoline today priced by geopolitics on top of uncharacteristic supply fundamentals.

From the view of the latter, the US complete PPI for finished goods, rate hikes for as far as the eye can see. This is a measure that includes an unhealthy dose of energy pricing, therefore what doesn’t seem any end in sight to what has become enormous producer pain. Despite the word inflation being thrown around carelessly, businesses are not passing the full brunt of input costs to consumers.

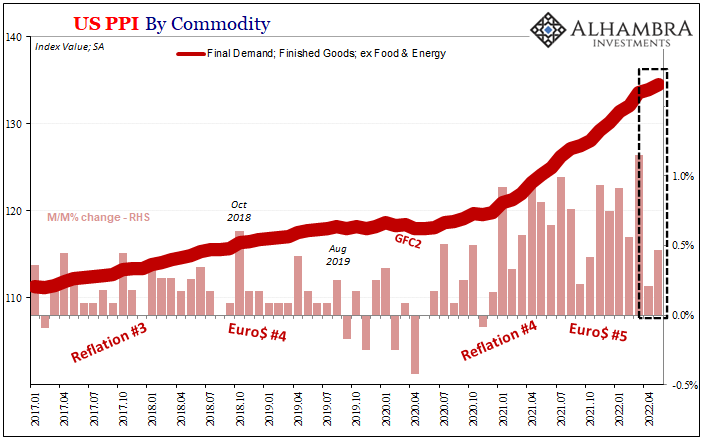

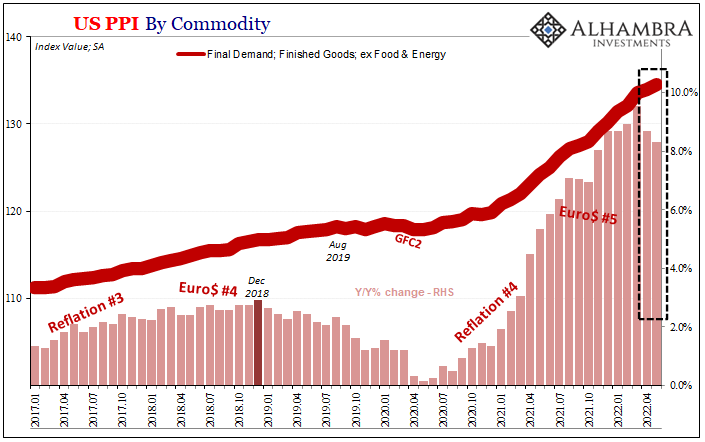

Separate out gasoline and oil, though, the PPI begins to look slightly askew when compared to its complete headline. The so-called core rate is now what sure seems to be two months into a slowdown.

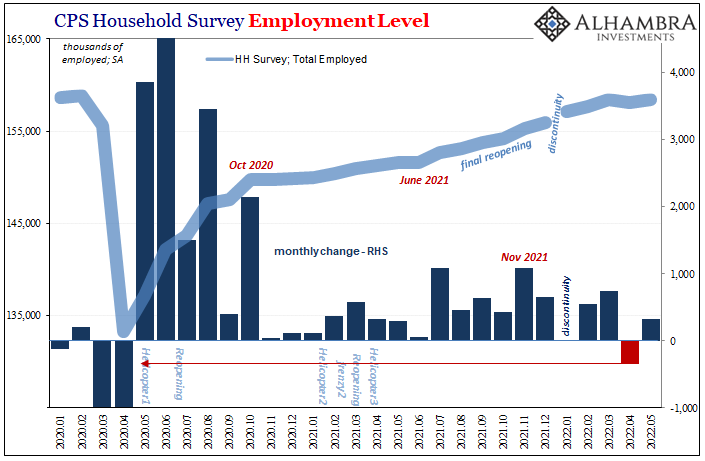

As always, usual caveats apply only starting with how this is just two months of core PPI data. It is, however, the same two months when the same possible inflection appears broadly across the US and global economy. American labor data, for instance, including the Establishment Survey, suddenly exhibits a material change; the Household Survey’s shock two-month drop in exactly these same two months of slower core PPI.

The public may hate that transitory doesn’t just disappear from the macro vocabulary after a couple days or weeks. Supply shocks take time to work themselves out, but work themselves out they will. Enough pain, because not enough legit economy, the downside case is inevitable if its timing beyond difficult to predict.

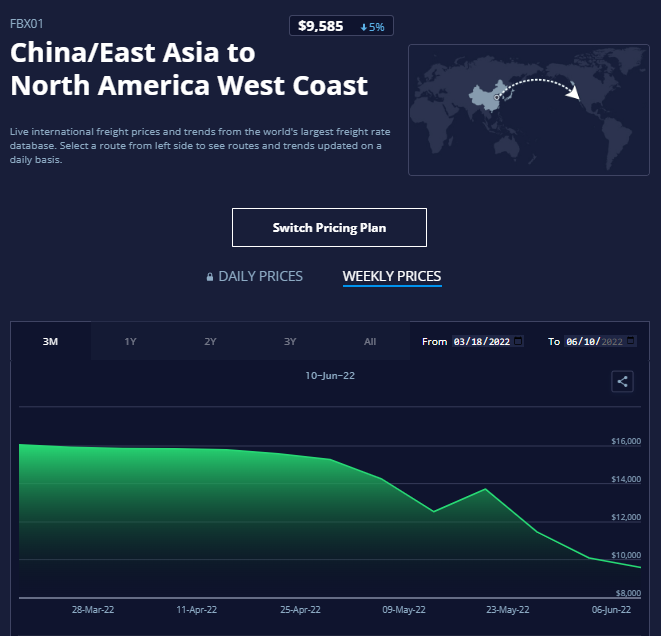

There’s a growing catalog of data adding witness to these same inflection-able months, too. Freight rates for containers have been a big one given how much these have made producer and consumer prices apart from energy. According to Freightos data, last week was another “unexpected” down week.

Their global index declined after a big drop the prior, largely due to the supply shock epicenter – China/East Asia to US West Coast – suffering another large and “unanticipated” drop, the rate falling below $10,000 for the first time since last summer. Since everyone has been led to believe we’ve been suffering from genuine inflation, it had been widely expected containers rates, in particular, would surge once China’s eastern ports were fully reopened.

They reopened and…nothing. It should grab everyone’s attention, but rate hikes based on political oil have.

Containers like the PPI or the Household Survey, Shanghai locked or unlocked hasn’t made a difference for the overall trend in pricing shipping. Back to March, same months in question, something has changed.

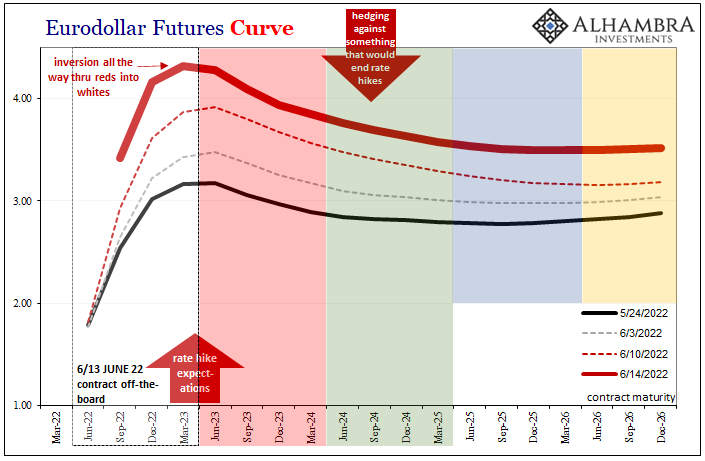

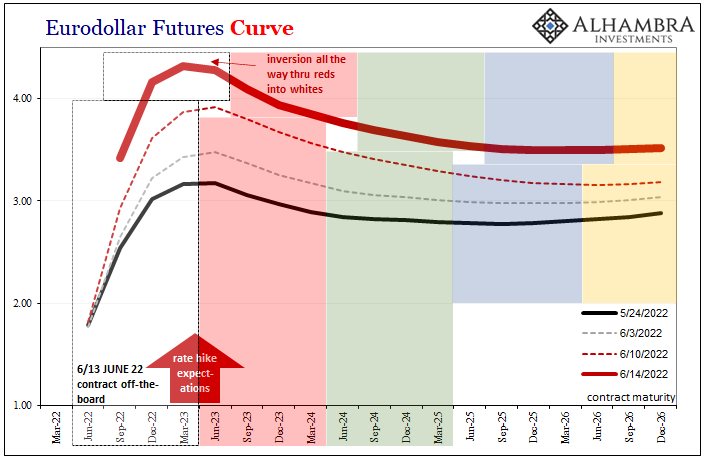

Aware of the non-economic considerations being cast around the FOMC’s current policy conferences, vast markets are anticipating a renewed resolve among policymakers to ignore these increasing, and increasingly forceful, recession signals across the economic and financial landscape.

Perhaps the most powerful and compelling in the latter class is eurodollar futures. This curve has priced the post-European ex-Russia gas fiasco as other markets have; hawkishness up front. Like Treasuries, inversion from there which has spread forward as it deepened.

As mentioned not long ago, a key sign for eurodollar futures is inversion moving all the way through the reds and into the whites. Reds completely flipped all the way over the past few weeks.

Today, inversion made its way into the whites with the June 2022 contract going off the board yesterday. The top contract in the trend is no longer a red June 2023, it has become a white March 2023 with the December 2022 not far behind.

I’ll add the usual interpretative curve guide here because people unfamiliar with this specific market typically make the mistake of taking the curve at face value, or literally. With the prior inversion pivot at June 2023, the market was never saying that specific June 2023 or next year’s QE would be when rates were thought to start coming down.

All curves are essentially probability distributions, and what that means is when inverted the market is hedging a very high possibility something bad happens between now and that contract (and those behind) which would lead to 3-month LIBOR being less than before that point on the curve.

Now that the pivot has moved up to March 2023, it’s the same; the market isn’t pricing a recession or financial trouble in the first quarter of next year compared to what had been the second quarter, rather eurodollar futures buyers are now more confident that this something bad will happen and that it is more likely to happen sooner than previously priced.

This, like all the “everything” I pointed out yesterday, fits neatly what we’re now beginning to see – even if only a few months to this point – out of a wide variety of accounts like US labor data and this core PPI to go along with freight rates.

It takes time for Euro$ #5 to get everything synchronized.

The Fed and its rate hikes are reactions to what is fast becoming old news. Oil and “inflation” politics may have invigorated the FOMC for the wrong reasons, glued exclusively to headline PPI or CPI.

Even this European-Russia inspired renewed focus and Volcker-esque (myth, anyway) determination won’t be able to hold up; that’s what these markets are betting anyway, just like last time during Euro$ #3. The amount of time the market prices they will get away with it is actually shrinking, thus, eurodollar and yield curve inversion, even though the rate hikes are likely to be more aggressive in the shortest run.

Stay In Touch