I spend a lot of time thinking about what “everyone” else believes about the economy and markets. If you’ve been reading my weekly scribblings for any time, you know I have little faith in the soothsayers of this industry. No one knows what the future holds, least of all that group of crystal ball gazers known as economic forecasters. Most of them do nothing more than extrapolate the current trend, which works pretty well until something changes. Of course, it is when things change – unexpected things – that large amounts of capital are made and lost so that’s a pretty significant shortcoming.

I don’t pay attention to these forecasts because I think they might be right. I pay attention so I can understand what everyone expects, what the consensus view is about the future economy and markets because it is when those expectations are not met that markets make big moves. Sometimes, there really isn’t a consensus, the forecasts are all over the map. And sometimes there is such a strong consensus that you’ll be accused of heresy for merely mentioning the possibility that it might be wrong.

I don’t think there is much of a consensus about the economy as a whole right now. I guess the closest you could come to a consensus is that a recession will happen fairly soon but not too soon. Maybe the end of the year or early next year but not now. That could be wrong in multiple ways of course and there is no real way to guess which outcome is most likely. We could be in recession right now – which seems highly unlikely – or we could be on the verge – which is more likely than right now, but by how much is unknown – or recession could keep getting pushed off to some date further in the future. But I don’t think this currently qualifies as one of those iron-clad consensus situations. Certainly not like last fall when everyone believed that the Fed was going to hike us into recession tout de suite.

Since we aren’t in recession now, that overwhelming consensus from last fall was wrong. If you’re a trader, short stocks and long bonds because you thought the consensus would prove correct, you’ve had a miserable 2023. For investors with a core strategic allocation, even if you did nothing, the outcome hasn’t been too bad. You’re up on the year although you could obviously be up more if you had added some NASDAQ or large-cap growth to your portfolio. The consensus in this case became extreme and it was pretty obvious. All the sentiment indicators we watch were at extreme bearish levels in October. And since you can’t forecast the economy, that’s what you need to look for – sentiment extremes.

There is consensus on some aspects of the economy. For instance, on inflation, everyone “knows” that inflation is going to fall over the next few months because the rent portion of the index will start reflecting the drop in housing prices last year. In fact, that consensus is so strong that markets have likely already priced in much of the improvement. If everyone knows that everyone knows that inflation is going to fall, it isn’t news and you have to start looking past the next few months to what happens after the base effect fades. And that is an area where there doesn’t seem to be any consensus, at least at first glance.

What is the long-term outlook for interest rates and inflation? There are two opposing views. One is that we will go back to where we were prior to COVID. In this scenario, inflation falls to 2%, or less, quickly, as the economy enters recession. In the extreme version of this scenario, the recession is severe, on the order of 2008 (because of banks and commercial real estate) and inflation turns to deflation. If you believe that and want to make an extreme bet on it, back up the truck and buy long-duration Treasuries, the longer the better. You should know before you do that this is already a pretty popular trade. TLT (20+ year Treasury ETF) has seen inflows of nearly $11 billion this year and $21 billion over the last year.

The other view is that this is, to use Howard Marks’ term, a sea change in the rate environment. In this view, inflation remains stubbornly high, rate hikes are not over and the long, 40-year downtrend in interest rates is over. If you compare this time to the late 60s and the 70s – as I have repeatedly so you kind of know where I stand – rates will have to go much higher than anyone today believes possible. You think today’s yield curve inversion is extreme? In the 1970 recession, the Fed hiked the Fed Funds rate to 3% over the 10-year Treasury yield. In the 1974 recession, the inversion was over 5% and in the 1980 recession, it was 7%.

The lack of consensus, in this case, extends to our firm. My partner Doug Terry is more in the disinflation/deflation camp while I’m more in the sea change camp. And I think that’s healthy, by the way. Investors should always question their views and regularly consider the contrary case. A healthy and respectful debate makes that easier. And in this case, Doug’s pretty damn smart, so I pay attention when we disagree.

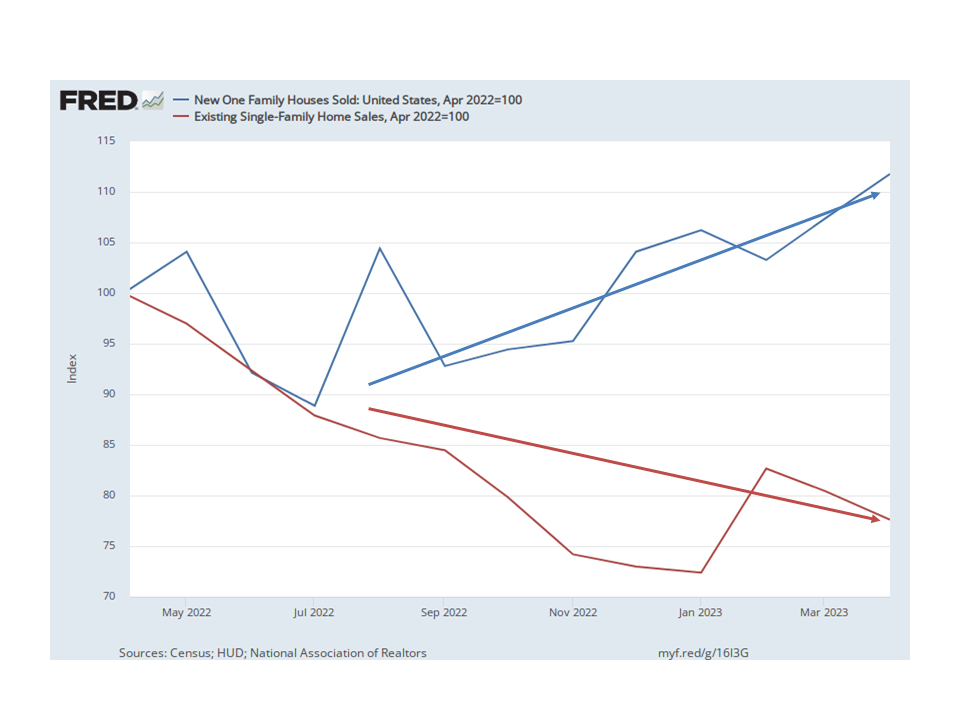

Recently, we’ve been discussing housing and the effect of the Fed’s rate hikes. The Fed’s rate hikes have impacted housing more than any other sector of the economy, in expected ways and in some unexpected ways. The obvious effect is that higher mortgage rates have impacted home sales by raising the cost of carry. The overwhelming consensus for most of last year was that higher mortgage rates would be disastrous for housing and that certainly looked true until the middle of last year. Doug included this chart in a recent post on housing:

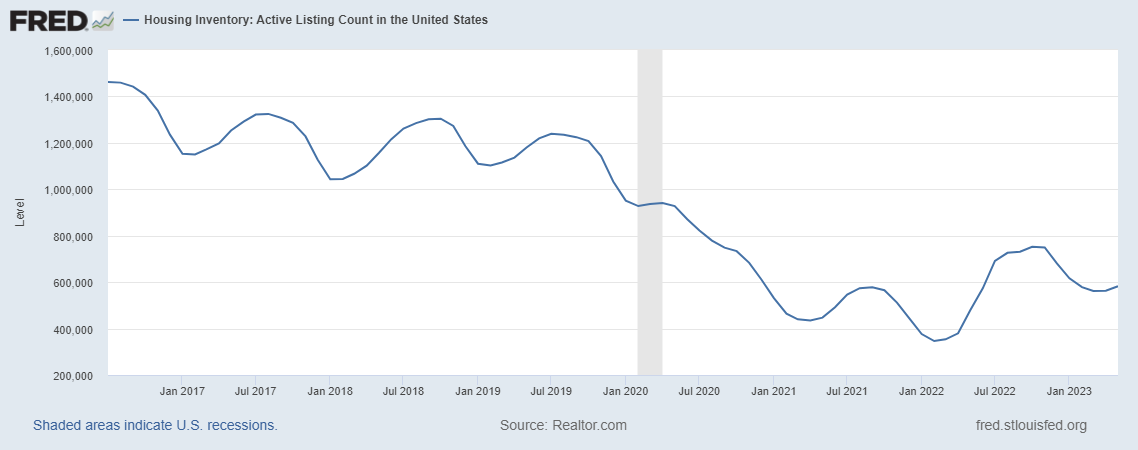

As you can see, existing home sales and new home sales diverged last year. One of the unintended consequences of the Fed’s rate hiking campaign is that it has frozen the existing home market. Anyone who bought or refinanced between 2020 and 2022 has a rate under 3.5% and they aren’t moving unless absolutely necessary. Moving and financing at 7% means downsizing for most everyone and no one wants to do that. And so, the number of active listings today is about half what it was prior to COVID and it wasn’t that high then. With little existing home inventory, sales have shifted to the new home market.

Which means the Fed’s attempt to slow the economy through rate hikes hasn’t worked that well. And for those of us in the higher-for-longer camp, the housing market is prime evidence that rate hikes aren’t working. Prices have resumed rising so any dip in inflation that results from lower rents, will likely be temporary. Why? Two words: housing shortage. Which is a problem for us in that camp because that is very much the consensus view, one that probably qualifies as extreme. Dissenting views on the housing shortage narrative are scarce, almost non-existent.

This is where I get to consider how my higher inflation era thesis might be wrong. Tenant and Owner’s Equivalent rent are 40% of core CPI and roughly 30% of the headline rate. The surge in the CPI over the last year has been driven by real estate and if the “housing shortage” consensus is right, knocking down core CPI is going to be hard. But what if it isn’t true? What if the “housing shortage” is (or was) temporary?

There are a number of reasons to question whether there is a long-term housing shortage. One of the main drivers of the recent shortage has been an elevated level of new household formation. But like so many other things, this trend has been distorted by COVID and the response to it. Living arrangements that made sense with COVID cash support and remote working may no longer be viable. At the onset of COVID, there was a rush of young people moving back in with their parents but that faded quickly as they gained the financial means to move out. And move they did; the percent of 25-34 year olds living alone rose to a record high.

If the unwinding of some of the COVID housing arrangements causes household formation to fall back to levels more in line with population growth by age group, new household formation could easily be cut in half from the elevated 2022 level. A cut of that magnitude would almost certainly pull down rents and maybe house prices too.

Demographics are the key to the housing market and there are definitely some negatives. Population growth was just 1% in 2022 and that’s double the change in 2019, 2020 and 2021. With immigration limited by politics, and the baby boomers aging, I would be surprised if we can even maintain 1% growth going forward. And the 20-24 age group – which would be the bulk of those new households – is no higher today than it was in 2014 and only about 6% higher than 1980.

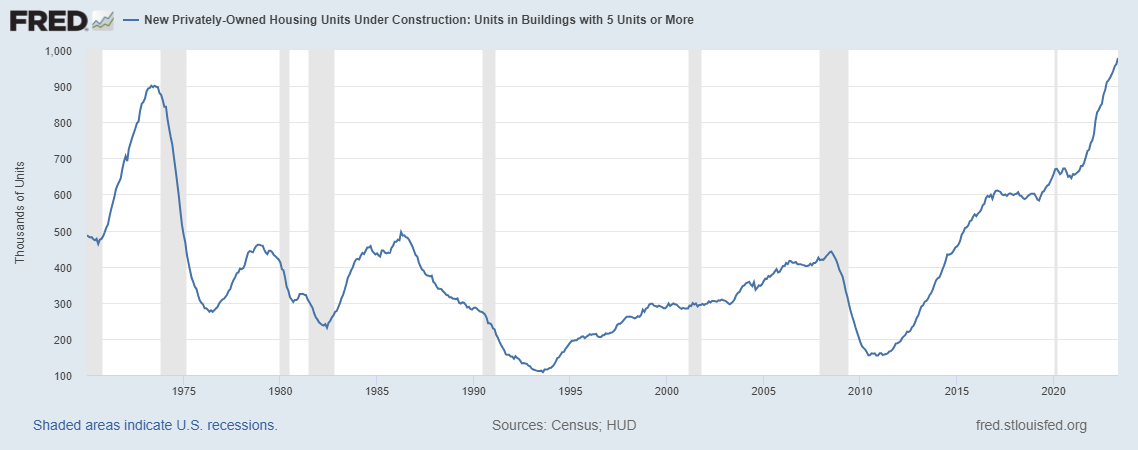

Also of note is the building activity in the multi-family space. Most of housing media coverage centers on single-family housing but any assessment of the housing shortage has to take into account all housing, including rentals. And there’s a lot of multi-family building going on. The number of housing units under construction in buildings with 5 or more units is at a record high:

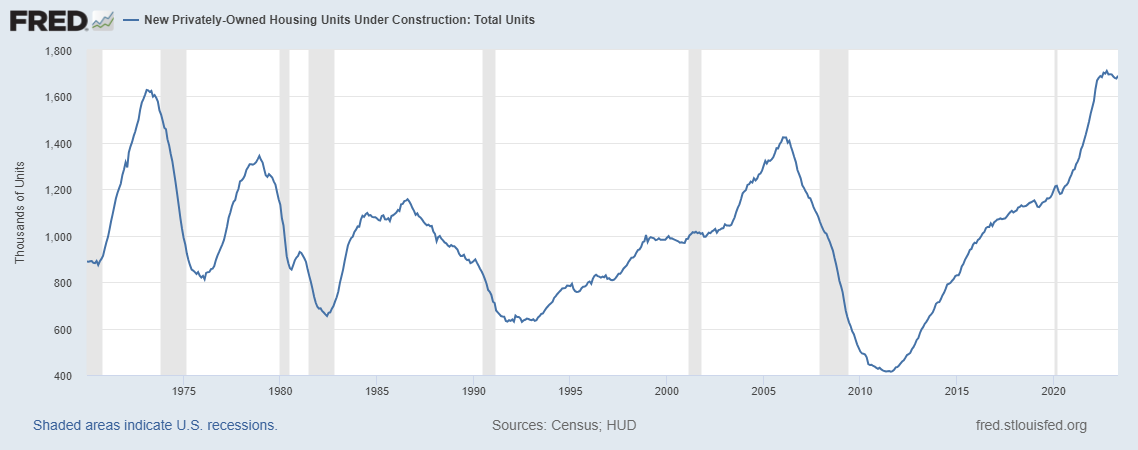

Total units under construction is also near a peak and may be turning higher again:

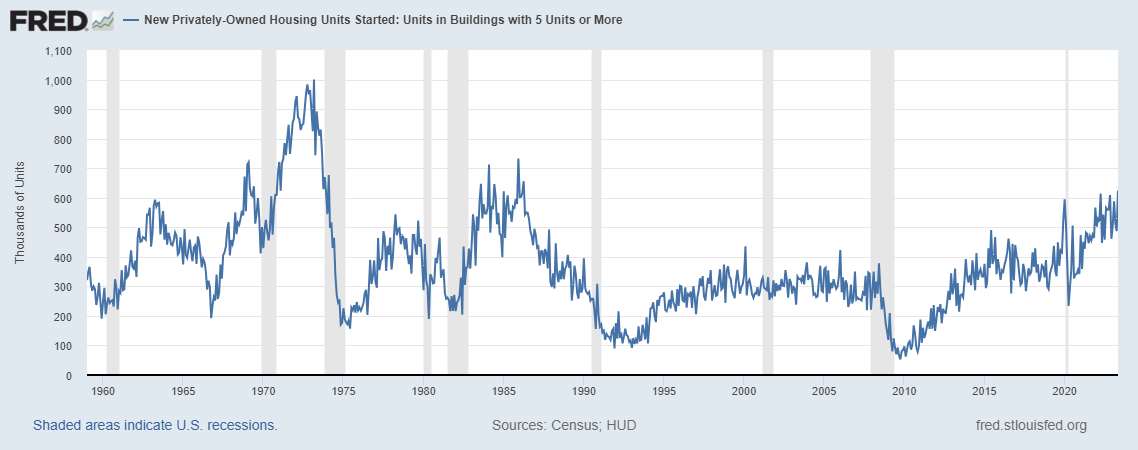

Multi-family starts are also above the long-term average. 5 plus unit starts, at 624,000 is well above the long-term average of 367,000.

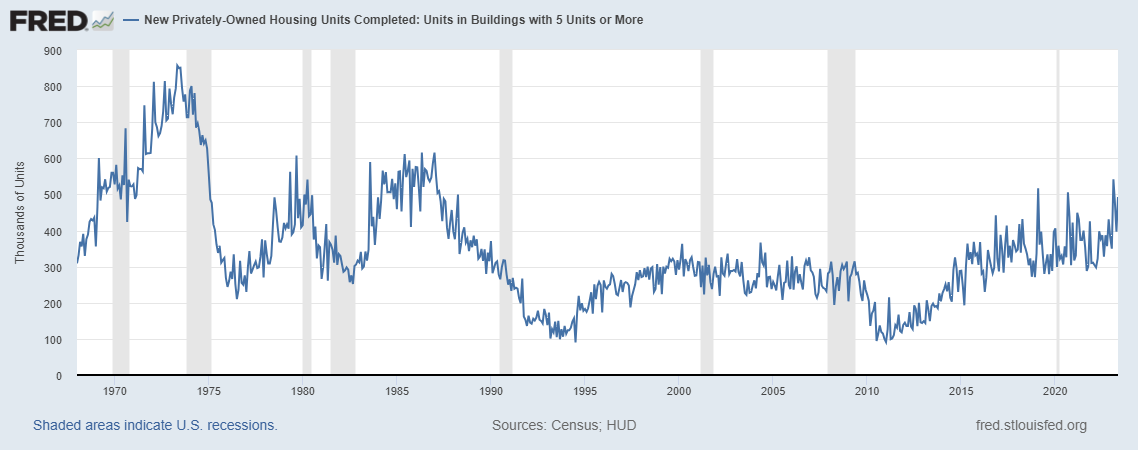

Completions are rising too:

Inflation isn’t about one item like housing. If we have truly entered a new, higher-inflation, higher-interest rate regime, then a moderation of housing costs would just be offset by an even greater rise in price somewhere else. But the current housing “shortage” may be nothing more than one more COVID distortion that will fade away with time. Even if there is a true shortage that developed because of supply chain issues or a labor shortage the market seems to be moving quickly to solve it.

It could well be that the Fed’s initial diagnosis was correct and the rise in prices we’ve witnessed in the wake of COVID was indeed transitory. In one important way, that actually makes a lot of sense. Inflation is ultimately about the purchasing power of our currency. While the dollar is down from last year’s high, it is still above most of the values that prevailed prior to COVID. That isn’t what I would expect if we were going to have an extended bout of inflation.

There are still some very good arguments for the sea change, higher-for-longer camp, most of them centered on fiscal (spending) policy so I’m not conceding the point yet. But I can see some pretty good arguments for the disinflation camp, especially in the short term.

To be continued…

Joe Calhoun

Stay In Touch