You’ve probably heard the phrase “soft landing” a lot lately. It has, over the last couple of months, become the new economic consensus. The economy continues to perform better than expected despite the Fed raising interest rates steadily – and fairly rapidly – over the last year. The most recent hike was just this past week and put the Fed Funds rate at 5.25-5.5%. A day after the rate hike the BEA released a report on Q2 GDP that showed the economy expanded by 2.4%, a result wholly unexpected by almost every economist who dared to publish an estimate.

The recession calls first started last year in April when the 10-year/2-year Treasury curve first inverted, although that inversion proved short-lived. But the curve inverted for good in early July and recession fears multiplied. They hit the panic level in October when the 10-year/3-month Treasury curve inverted, which, ironically, proved to be the bottom for the stock market. The consensus coming into this year was that recession was imminent, likely to start in the first half of the year. Instead, real GDP has grown by 1.1% (actual, not annualized) over the first two quarters of the year, right on trend.

And so, since it hasn’t come on the previously expected schedule, the consensus has shifted to expectations for the fabled and rarely seen “soft landing”. Economists rarely just say, hey, I was wrong; the shift to the soft landing scenario allows them to say, no I wasn’t wrong, we’re still going to get a slowdown, just not enough to be called a recession.

What is a soft landing? Well, there isn’t an actual definition of which I’m aware and it didn’t come into wide usage about the economy until the late 80s, but it’s pretty easy to figure out. A soft landing is when the Fed raises interest rates to reduce inflation and manages to do so without causing a recession. We have had Fed rate hiking campaigns before that didn’t result in recession and they are rare but then so are recessions. The ones I’m aware of are:

- 1965/66 the Fed raised the funds rate from 3.9% in January ’65 to 5.8% by November of 1966.

- 1983/84 the Fed raised the funds rate from 8.5% in February ’83 to 11.6% by August of 1984.

- 1994 the Fed raised the funds rate from 3.1% in January to 6% by June

Maybe there were more prior to that but that covers the last 50+ years. Frankly, I don’t think the soft landings are all that interesting and I credit them more to luck than skill in any case. What is amazing to me is that we’ve only had 9 recessions in the last 63 years. Those nine recessions lasted a total of 95 months or just 12.6% of the 756 months during that time. We spend an inordinate amount of time and effort to avoid something that has odds in any given month of about 7 to 1. Not exactly a long shot but not the betting favorite either. Of course, with odds like that, betting on it and getting it right does have a pretty good payoff. But if you bet on it repeatedly for a long time – and sitting in cash while the market goes up is a form of that bet – the payoff usually isn’t large enough to make up for what you missed.

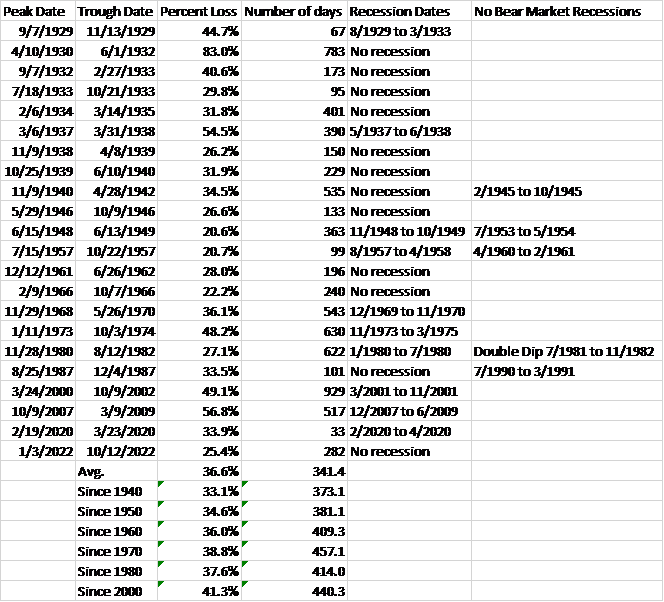

Unfortunately, it isn’t just the recession you have to get right to get the payoff. Bear markets are not synced with recessions, usually starting before the recession starts and ending before the recession ends. And just to make it a little harder, not always. And to make it even harder, there have been multiple bear markets that weren’t associated with recession at all (12 since 1928). One last little monkey wrench; there have been recessions with no bear markets (5 since 1928). In general, investors spend a lot of time thinking about one aspect of the macro-economy (recession) and even if they got it right, it wouldn’t do them much good.

That doesn’t mean we should just ignore the economy and invest, oblivious to the environment within which we do so. We will have another recession and we will probably get a bear market in proximity to it. But we don’t and can’t know when it will happen. The future is not knowable; I can’t predict it and neither can you. None of us knows when the recession will start. And none of us knows how that recession will affect markets beyond a general outline.

But there are things we can know about the economy that are useful. The most important information is readily available and has little to do with the economic data released every week. We can, through markets, determine what people expect from the future economy. It is those expectations that drive markets and it is when those expectations change that markets move the most. The soft landing scenario is expressed right now in the Fed funds futures market, a reflection of expectations regarding future growth and inflation. Right now, the CME’s Fedwatch tool shows a better than 50% chance that the Fed Fund rate is unchanged through at least January of next year.

And after that, the market only expects one rate cut by May of 2024. That is the soft landing scenario writ large. And we know that it is likely to be wrong. The current soft landing chorus is a pastiche of every past pre-recessionary period back to when the term first came into widespread usage in the late 1980s:

The Fed’s Fabled Soft Landing? It’s Actually Happening

Tim Duy, Bloomberg, April 7th, 2019

Fed chairman projects ‘soft landing’ for U.S. economy

Edmund Andrews, New York Times, February 15th, 2007

A Soft Landing?

Robert Samuelson, Washington Post, June 21, 2000

A SOFT LANDING?

Robert Samuelson, Washington Post, June 14, 1989

A consensus forecast by 27 economists who met recently at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland calls for continued slow growth in output and a “soft landing” for the economy through 1990. However, their projected inflation rate is relatively intractable and prospects for lower inflation in the near future do not appear promising.

John Erceg, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, July 1st, 1989

So, the fact that the soft landing has become consensus is not surprising. And it is probably wrong. Now each of the above instances turned out to be wrong because recession came fairly soon (in some cases the economy was in recession when the article was published). But that isn’t how it has to happen. The consensus could be wrong in a myriad of ways. Maybe, the market is underestimating future inflation or growth. Or maybe recession is right around the corner.

The focus on recession is, in my opinion, short-sighted. It is much more useful for investors to focus on what happens between recessions, what happens regardless of recession, how the economy is evolving over the long term. There are big things happening in the economy and that will be true regardless of whether we enter recession this year or next. The US is still going to have an aging population. The need for electrical infrastructure investment is not going to abate. Technology and science will continue to advance. Automation, robotics and artificial intelligence are all more important to future growth than anything the Fed might do.

The gains from predicting the onset and end of recession could be large but the odds of success are very low. And the consequences of getting it wrong are often greater than the gain of getting it right. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be interested in the ebbs and flows of the economy. But it does mean you shouldn’t make any big bets on it. Watch the economy and the consensus and how it is changing. When sentiment is dour, assume it will improve. When it is exuberant, assume it will sober up. Act as a contrarian but only incrementally.

I’ve said this many times before but I think it bears repeating. Investing is a loser’s game, one that is won by making the fewest mistakes. There will be times, sometimes fleeting, when the payoff from being bold is so large you have to make the bet. But those moments, periods when sentiment becomes so extreme it can’t last, are rare. The rest of the time, investors are much better served by making only small changes to avoid large mistakes.

Environment

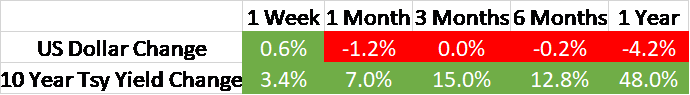

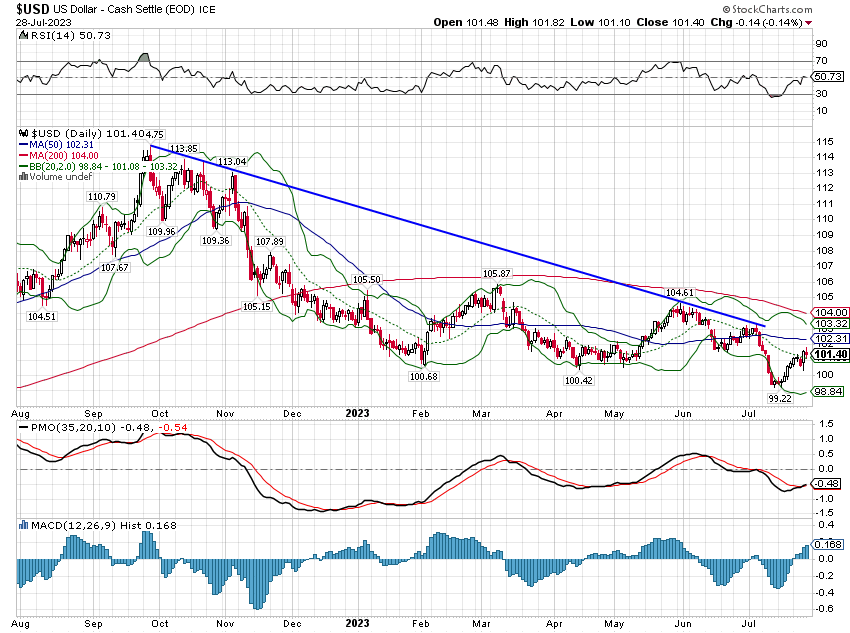

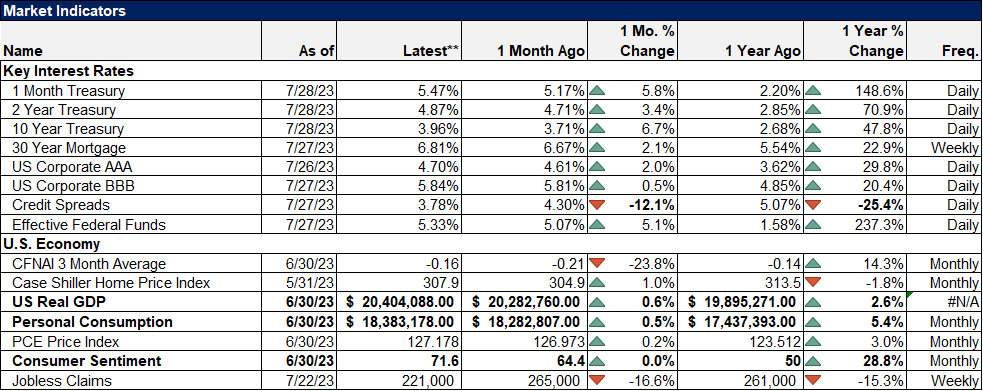

The dollar was pretty firm last week in the wake of better-than-expected US economic data but the short-term trend remains down. Consumer confidence and sentiment continue to improve. The former has risen considerably since the lows of last June, especially the expectations index. Expectations were at 65.3 last July and now stand at 88.3, up 10% in just the last month. That’s also, by the way, well above 80, the level that historically signals a recession in the next year.

Consumer sentiment also continues to improve, with the University of Michigan poll rising to 71.6 from 64.4 last month. That is still well below the long-term average of 85.6 but it is also way above the all-time low of 50 set last June. What’s important about sentiment, as it is with so many economic indicators, is how it’s changing not the level. Rising consumer sentiment doesn’t happen during recessions.

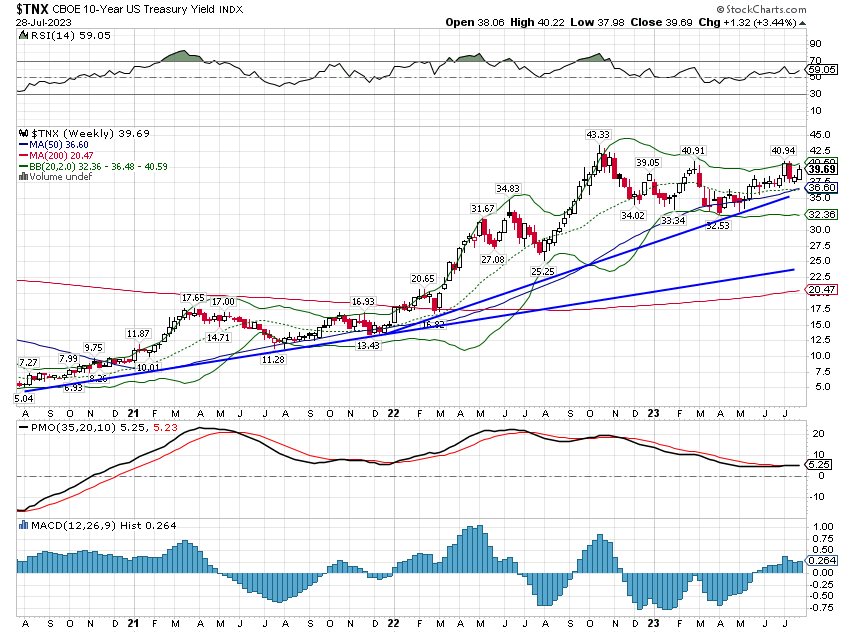

The 10-year Treasury yield uptrend, short and intermediate term, continues.

Shorter maturity yields were also higher but the uptrends have recently stalled somewhat, a reflection of reduced expectations for future Fed rate hikes; the Fed is figured to be on hold. We’ll see I suppose but I think the market might be a little too comfortable with the idea that the rate hike cycle has ended.

Markets

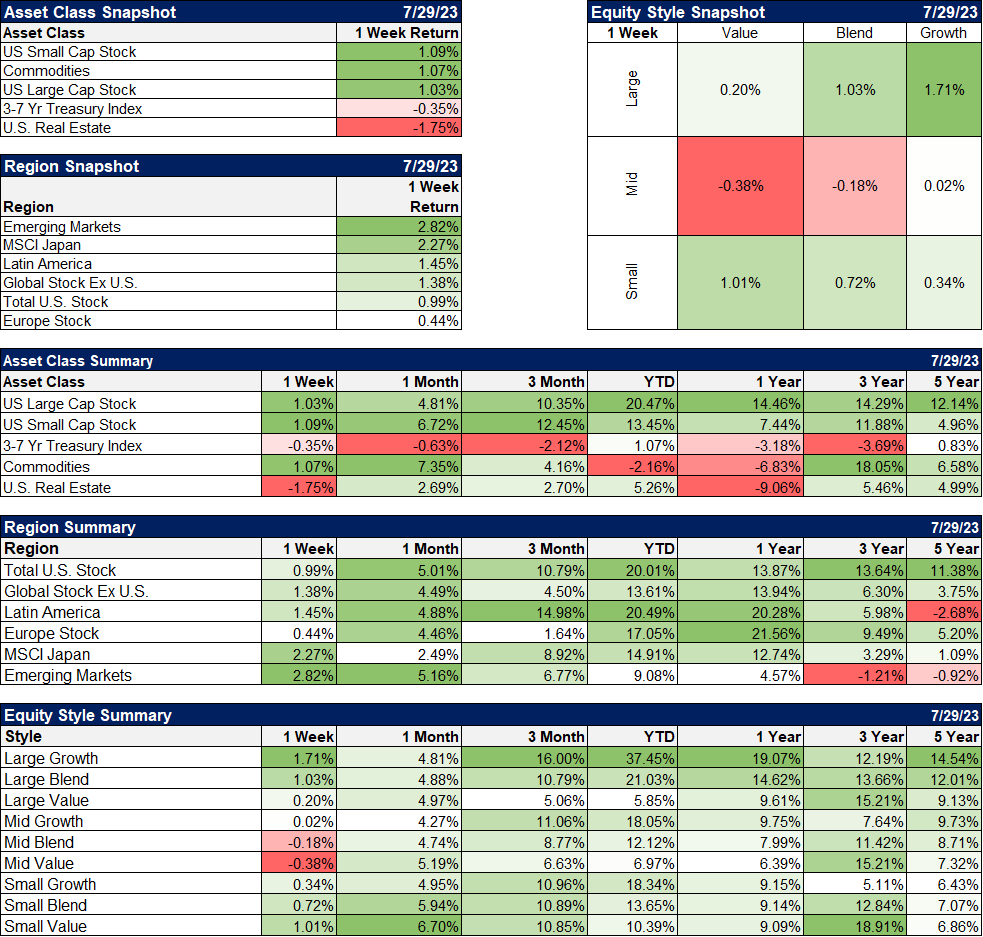

Stocks and commodities were up about the same last week while rate-sensitive real estate fell. International markets outperformed the US, as they have over the last year. The key to that outperformance has been the weakening dollar. I expect that tailwind to persist in the long term but the dollar downtrend has definitely stalled a bit lately. Currencies shift based on growth expectations so it isn’t surprising the dollar has been firm recently. The surprise may be that it isn’t stronger.

Small-cap value and large-cap growth were the leaders from a style standpoint last week. Those two don’t travel together often so don’t expect it to last. Either large-cap value or small-cap growth will emerge soon. A weak dollar tends to favor value stocks so watch the buck for clues.

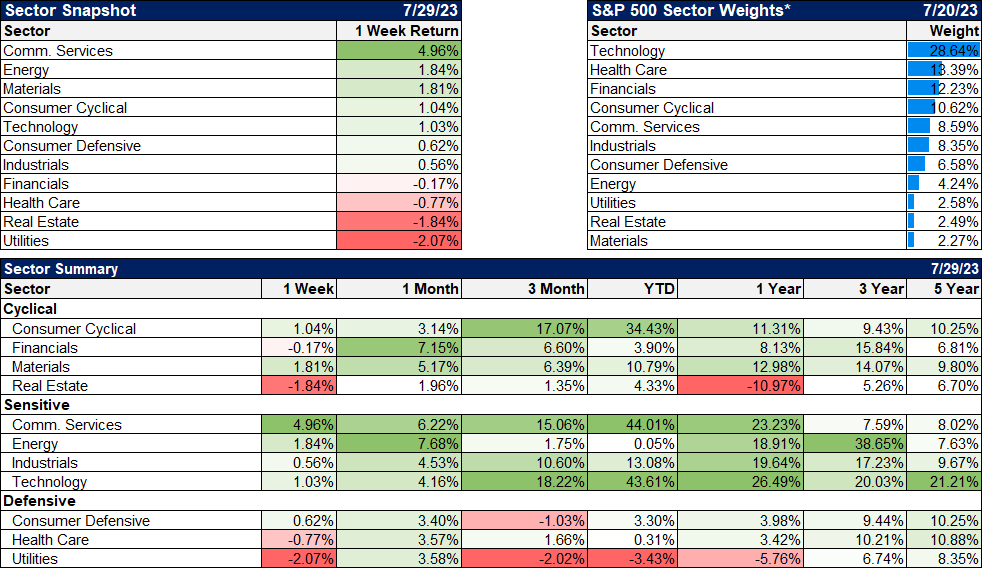

It was communications services leading again last week which means Alphabet and Meta, two companies known more widely by their old names (Google and Facebook), had great weeks. Both reported better-than-expected earnings which has been a pattern so far this earnings season. With about half the S&P 500 companies reporting, 80% of them have reported higher than expected earnings while 64% better than expected revenue. Earnings are, however, coming in less than last year, down about 7% year-over-year.

Also having a good week were the energy stocks with crude oil up 4.5% on the week. Materials and cyclicals were also higher while defensive stocks (healthcare and utilities) fell.

Economic/Market Indicators

Home prices are on the rise again, up for the 4th month in a row although down 1.7% from last year. A lot of people have been counting on lower rents to bring down CPI but house prices are part of that calculation and they haven’t been inflation friendly this year. With energy rising again, the surprise to the consensus may be that inflation remains high rather than continuing to moderate as everyone expects.

For the really big picture on the economy, the CFNAI (3-month average) shows an economy growing just below trend. The current reading of -0.16 is well above the -0.75 associated with recession and just below the zero reading for trend growth. Last month’s reading was down but the low for the 3-month average was last December and the more recent data has been stronger.

What matters for investors and markets is not the absolute level of any given economic metric. It is how the data is coming in relative to expectations that matters and moves markets. The market provides us with numerous ways to observe those expectations, in interest rates, exchange rates, and stock prices.

Investing is about the future but it doesn’t require clairvoyance. All it really requires is that you pay attention and interpret the present. That isn’t easy but it is a lot easier than guessing the future.

Joe Calhoun

Stay In Touch