I’m back! I took most of the month of December off, as I do every year, to do some thinking. Per the title of this essay, the purpose of these year-end musings is to gain some perspective. In the day-to-day, week-to-week, movements of the markets it is easy to forget that we are investing with a timeline measured in years, and for many investors, decades. I write a commentary every week for 11 months of the year and I rarely lack for something to write about; there’s always something going on with the potential to impact markets and portfolios. Most weeks though, to be honest, the news isn’t really all that important for investors. You can follow the economic reports as they’re released but most of them are going to be about as expected. Yes, some will be off the consensus by a little, but does it really matter if the latest inflation figure was 0.1% higher or lower than “expectations”? The answer to that is obviously no since whatever is reported this month will get revised next month and probably several times after that. The precision we want in economic reports just isn’t available in real-time. Do you really want to fine-tune your portfolio based on data that isn’t accurate?

There are other matters that affect our investments of course but most of them not as much as we think. Politics can have an impact but the changes from administration to administration tend to be incremental and the effects inevitably exaggerated by politicians of both parties. Presidents just don’t have the power they or their supporters imagine and both parties are subject to the same lobbying from the same quarters. Washington DC is just as much a cesspool today as it was 100 or 200 years ago and I highly recommend ignoring most of what transpires there. Much more important than politics is the innovation from the private sector that continues regardless of which party is in power. Scientific advancements in recent years have been nothing short of amazing and it makes me optimistic about the future. But it takes time and a lot of trial and error to figure out how new discoveries will be put to use to improve our productivity, our lives, and our society. Most of the capital invested in the early years of the internet was wasted but what survived and adapted made a huge difference in our lives. Social media is proof that, decades later, it is still an ongoing process. The same will likely prove true of advancements like MRNA technology, gene editing, artificial intelligence, and other recent developments. In other words, the impact on the economy will be gradual; you don’t have to rush.

That doesn’t mean we should just ignore the economy, although a little perspective does come in handy. There are legions of “analysts” on Twitter and TikTok and blogs who are more than happy to exploit the latest economic release to get you to part with some hard-earned cash to subscribe to their service. Social media has devolved into psychological warfare with gurus (pronounced “charlatan”) pontificating on the latest economic release and how it confirms their view of the world even when it doesn’t. The only rule for gurus seems to be that one can never admit to being wrong. If the latest data point is so obviously counter to their previous pontifications, they’ll shift to some arcane subject that no sane person can possibly comprehend – least of all the gurus themselves – and explain why that means that they’ll be vindicated in the end, just you wait and see. With all this allowin’, reckonin’ and speculatin’ going on (as my father used to say), resisting the temptation to do something when you should probably be doing nothing is harder today than ever before. The only way to avoid the temptation is to get a little, you guessed it, perspective.

This time of year, there are hundreds (thousands?) of economic and market outlooks available, all focused on what is going to happen over the next 12 months. These “outlook” pieces are remarkably similar from firm to firm, proving that job security on Wall Street is often found in consensus. They are also very similar year to year (stocks are always expected to perform near the long-term average even though they never do) and this year is no exception, with a theme remarkably similar to last year’s – which turned out to be spectacularly wrong. Everyone sees the economy slowing, most to a soft landing, others to a mild recession, a few others to a hard landing, and a few outliers calling for something outside the norm (if at first, you don’t succeed…). Bonds are the preferred investment vehicle as the Fed and other central banks are widely expected to cut rates as the economy slows. Quality stocks are to be emphasized (are there times we should emphasize low-quality stocks?) and the US is generally the place to be, despite “challenging” valuations, as several firms put it so delicately.

Markets currently reflect the consensus of a slowing economy with Fed Funds futures currently showing a 69% chance that the overnight lending rate will fall to a range of 3.5% to 4.25% by December of 2024. That expectation of rate cuts next year is what moved stocks in the 4th quarter of last year; a lower discount rate means investors can put a higher value on future, often speculative, earnings. Of course, earnings could be negatively affected by a slower economy but if the economy avoids recession, earnings shouldn’t be affected that much. Indeed, if rates fall because inflation continues to fall, margins could expand, raising earnings despite slower nominal growth. And the drop in rates, at least so far, does not indicate a recession.

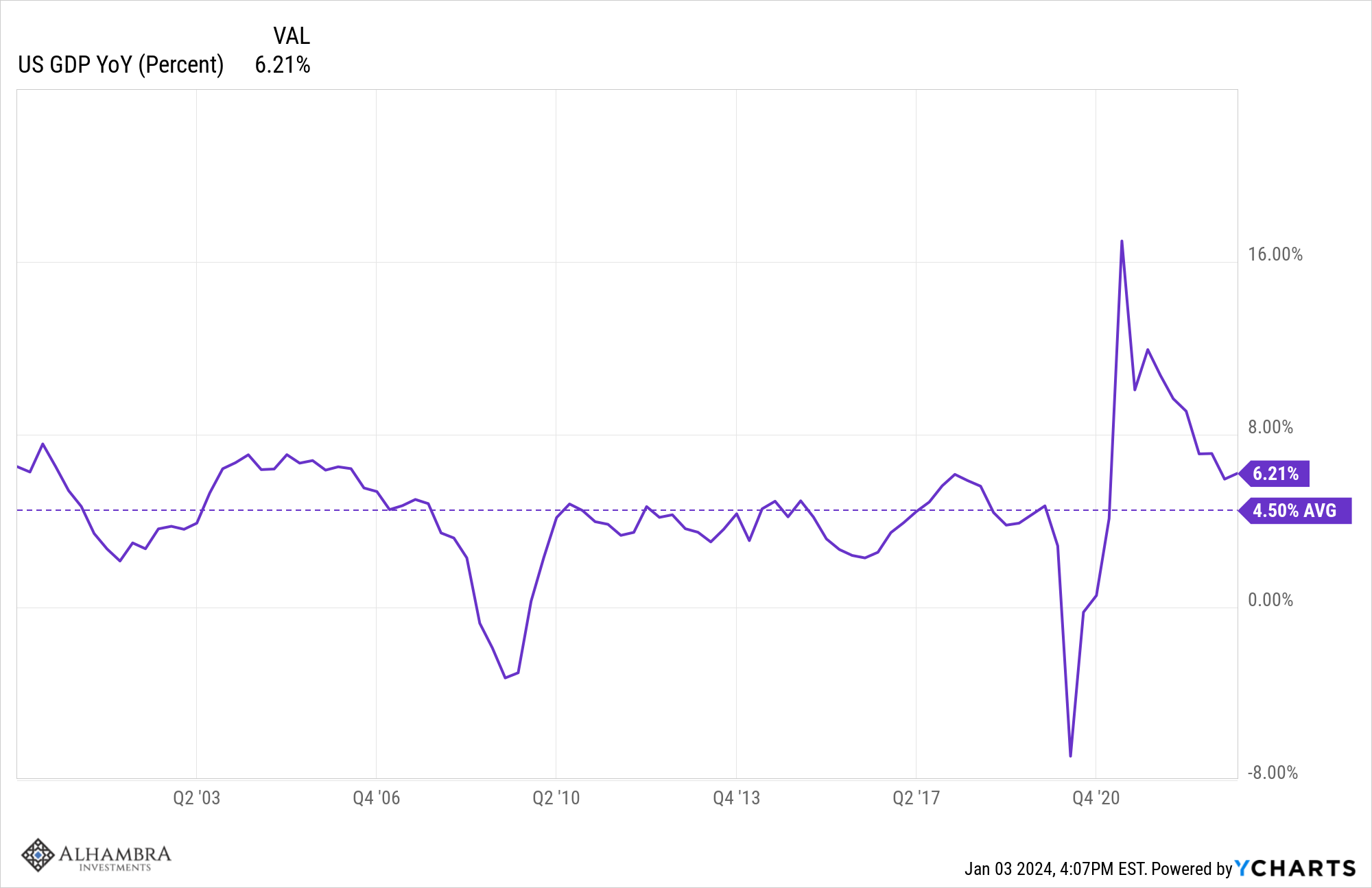

The 10-year Treasury rate is a good proxy for nominal GDP growth and at the current 4%, the bond market is merely factoring in a return to trend real growth of 1.8-2%. The year-over-year change in NGDP after Q3 2023 was 6.2% and if inflation is going to continue to moderate that has to come down. NGDP is inflation + real growth but we never know what the split is going to be. Over the last year though, NGDP fell entirely due to a fall in inflation. In Q3 2022 NGDP was up 9.1% yoy and that fell to 6.2% in Q3 2023 while RGDP growth rose from 1.7% to 2.9% yoy. The market seems to be betting that will be repeated and it could happen. Right now the best estimates we have for real growth and inflation for Q4 2023 come from the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow and the Cleveland Fed’s Inflation Nowcasting. Using those two estimates puts Q4 NGDP at 4.3% with 2.5% real growth and 1.8% inflation.

What all that means to me is that the economy is returning to “normal” or what passes for it in the 21st century. The average year-over-year change in NGDP since 2000 has been 4.5%.

That’s all we know right now, that the economy is just about back to its pre-COVID norm. That isn’t an insignificant achievement by the way and one that not many people expected. It seems pretty obvious in retrospect since COVID didn’t permanently impact the things that create economic growth – workforce growth and productivity growth. The government borrowing and spending a boatload of money doesn’t move the needle on either one of those (except maybe in a negative way). There have been some positives, mostly in the form of household and corporate balance sheets, but the trade-off was a worsening of the public fisc; there are still no free lunches. From a macroeconomic perspective, I suspect that is a slight positive but mostly a wash. Workforce growth isn’t going to increase significantly because it can’t, absent a big change in immigration policy. Productivity growth, on the other hand, may well be the surprise of the next decade or so. Technology is the key and it seems to be advancing on several fronts, from AI to robotics.

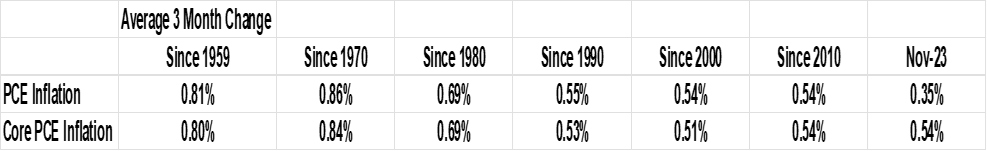

Shorter term, with everyone looking for an economic slowdown, the surprise may be that we don’t get much of one. Inflation is, at this point, back to normal. Yes, prices are still elevated over pre-COVID but if you’re expecting the Fed to tighten enough to push prices back down you need to adjust your expectations. That just isn’t going to happen. The 3-month change in PCE inflation hit its peak in March 2022 at 1.97% and has since fallen to 0.35% in November 2023. The three-month change in Core PCE inflation peaked in December 2021 at 1.61% and has fallen to 0.54% in November 2023. The last 5 measures of the three-month change since July are 0.58%, 0.39%, 0.55%, 0.58% and 0.54%. Maybe there is more trouble to come but that looks like inflation has stabilized to me. Given that and given that current monetary policy is at least somewhat tight (see real interest rates), the Fed may well feel justified in an easing of policy. As I said, current levels of PCE inflation are about as normal as you can get, at right about the average since 1990:

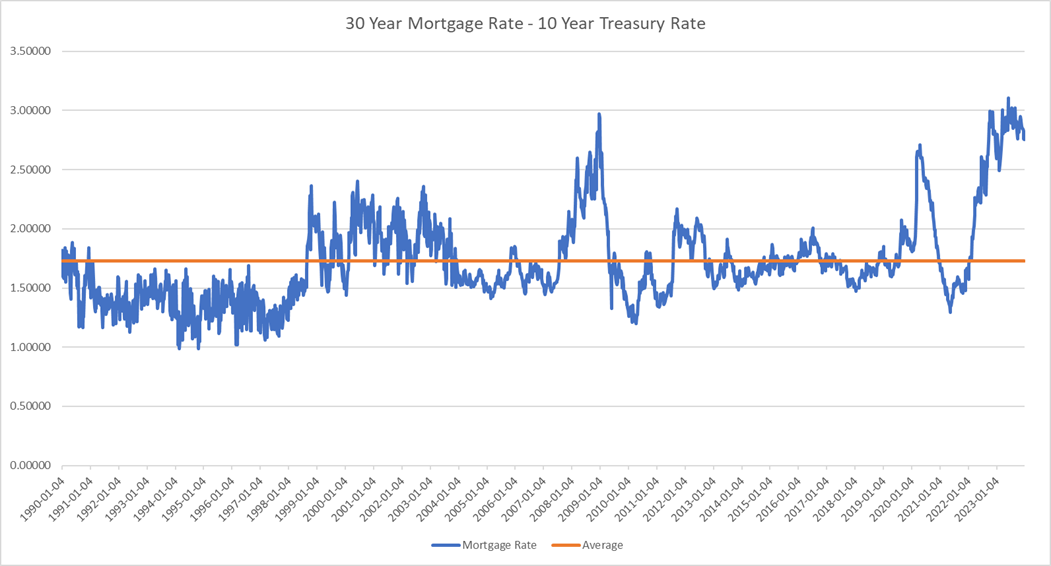

If the Fed does ease and long-term interest rates just stabilize at current levels, there is the potential for an upside economic surprise that doesn’t exacerbate inflation. The only area of the economy hit in any significant way by higher interest rates was real estate. With so many homeowners sitting on mortgages with 2 or 3 as the first digit, existing home sales have cratered. Mortgage rates are elevated because of the Fed’s rate hikes but they are even higher because the spread between the 10-year Treasury and the 30-year mortgage rate is wider than normal:

The average spread since 1990 is 1.72% versus the current 2.75%. If the 10-year rate stays where it is and the spread narrows to average, the 30-year mortgage rate would fall from the current 6.6% to 5.6%. While that isn’t 3%, it is a lot less than the 7.8% peak in October of last year. I don’t know how much housing movement a drop like that would spur but the right answer surely isn’t zero. If mortgage rates do fall that much, more activity in the housing market could be a big boost to the US economy. Not only would more affordable homes mean more building activity but more existing home inventory could well keep prices in check. The knock-on effects could include increased home improvement activity and durable goods purchases associated with housing activity. The wholesale inventory/sales ratio is still elevated from the COVID supply chain issues but inventories have fallen for 11 months in a row. An uptick in sales associated with housing could easily bring down the ratio and spur new orders for a manufacturing sector that has been in idle for over a year. All of that is speculative of course and highly dependent on interest rates at least not rising much from here but if inflation truly is tamed, at least for now, then it becomes much more likely.

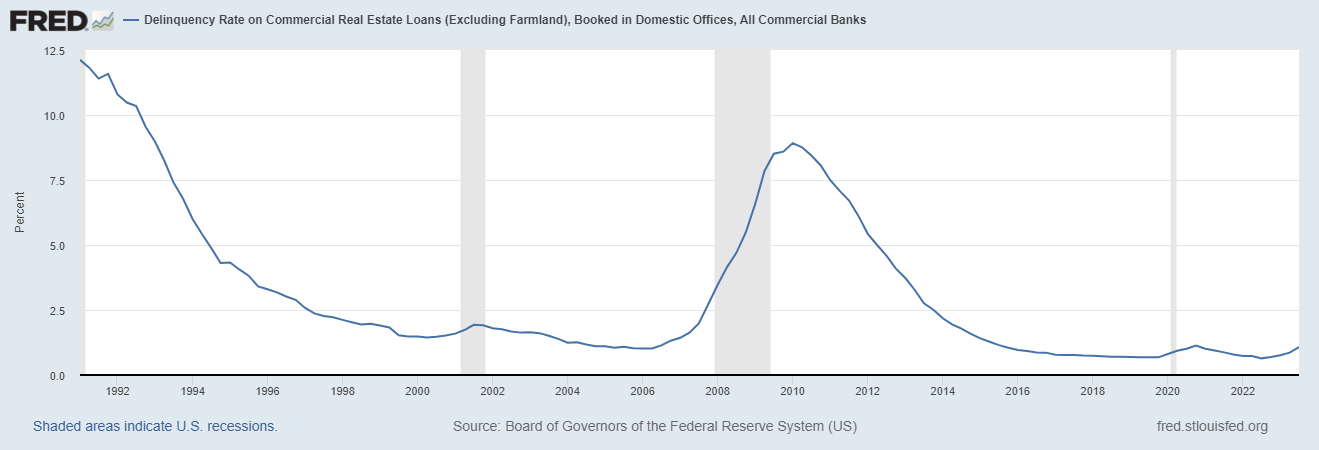

Lower rates would also be very welcome in commercial real estate. Poor quality deals done over the last few years at very low rates are already going bad as cap rates rise and refinancings come due. While I don’t think publicly traded REITs are much of a problem (with the exception of some of the finance REITs which we avoid) most commercial property is privately owned. Banks have exposure there – although not as much as you might believe from the headlines last year – but lower rates would solve a lot of these problems just as they are solving a lot of the banks’ unrealized Treasury losses problem. A tightening of mortgage spreads will depend on banks competing for loans and there is some potential good news there. The Senior loan officer surveys, conducted quarterly, show the percentage of banks tightening lending standards (for a variety of types of loans) peaked last year. In any case, the delinquency rate on commercial real estate loans is rising but it is still pretty low, less than the late 90s and the entire period until the 2008 crisis.

The US economy, for now, is back to the pre-COVID growth and inflation trends. I see nothing in the current data or market indicators that threatens imminent recession. Interest rates have come down with inflation, credit spreads are back near the lows of this cycle and as low as they got in the last cycle. Various versions of the nominal yield curve are still inverted, frustrating those looking for surefire recession indicators and still not having much of an impact on the economy. The real yield curve, measured by TIPS from 5 to 30 years, is flat and has been for most of the last year. Just a thought but maybe real rates are more important than nominal. We enter 2024 with the same fears as last year. Let’s hope they prove just as unwarranted.

Markets

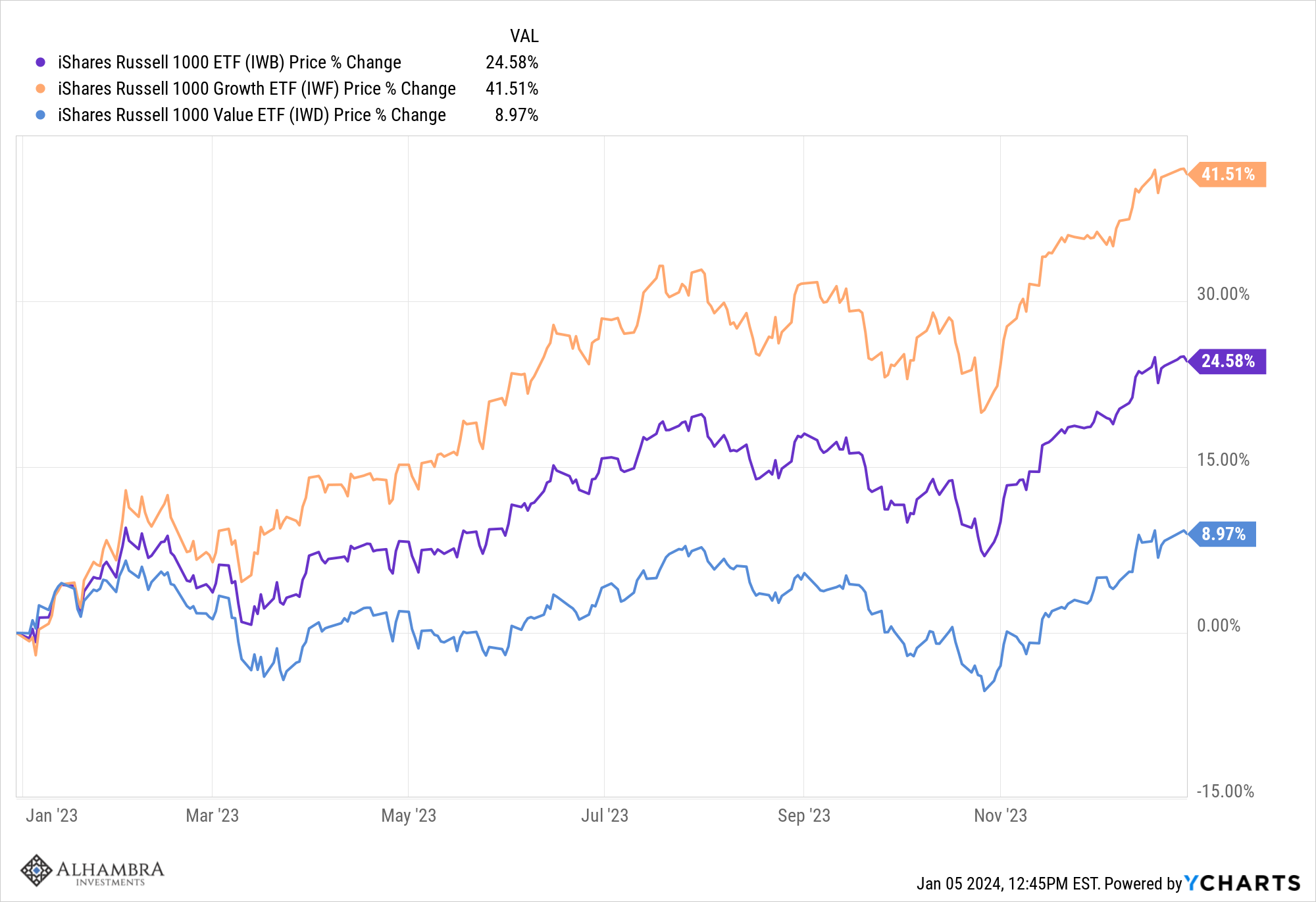

As with the economy, it helps to zoom out when looking at market trends. The big news last year was the outperformance of large company growth stocks relative to everything else. The Russell 1000 Growth Index was up over 40% last year while the Value portion was up just about 9%, which would have been a good result in almost any year but last.

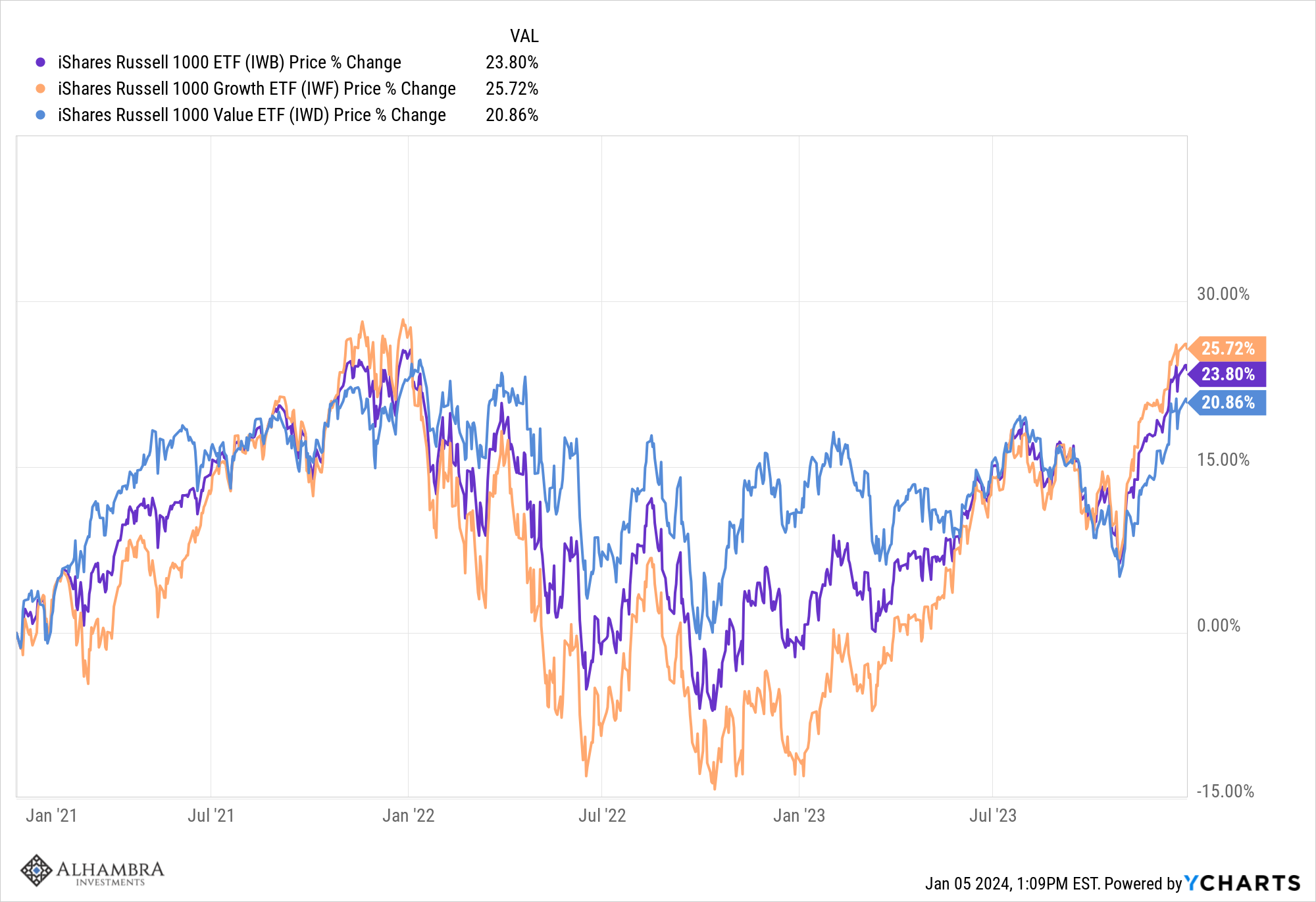

But growth’s outperformance last year was merely making up for the vast underperformance the year before. Over the last three years, growth still outperformed but the difference wasn’t nearly as wide. More importantly, the ride was a lot easier in the value index. From the beginning of 2021 to the end of 2023 the value index never traded more than 1% below the starting value while the growth index fell over 14%. The worst peak-to-trough drop – from the beginning of 2022 – for the value index was 20% while the growth index fell 35%. A 20% drop isn’t pleasant but it’s a heck of a lot easier than 35%.

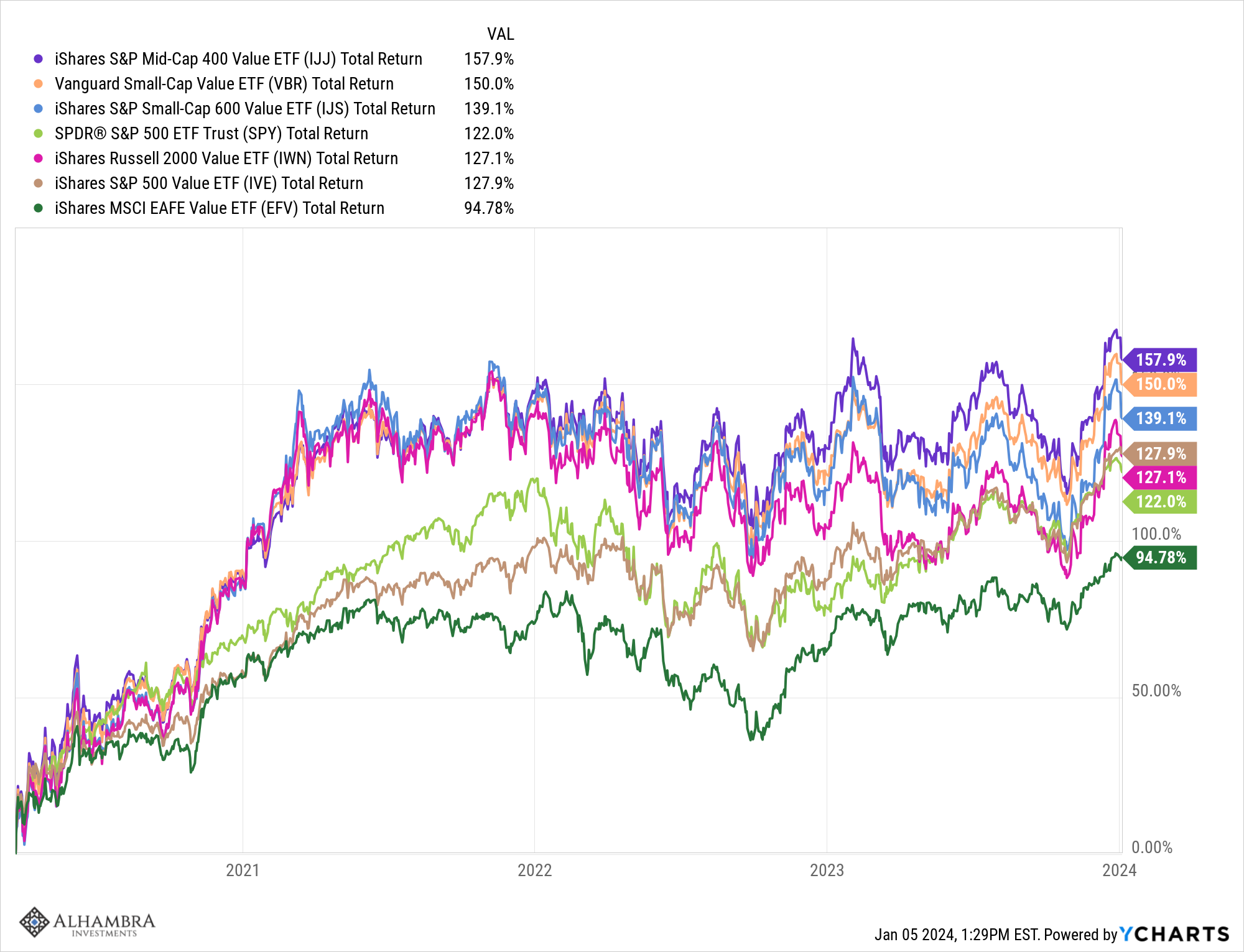

So, yes if you were a value-oriented investor – and we certainly fit that category – your portfolios didn’t do as well as they would have if you had shifted to growth stocks last year. But we aren’t really interested in short-term trends; we’re looking for trends that will last years and we continue to believe that the emerging one today is in favor of value, small/mid-cap, and international. Since the bottom of the COVID drawdown in March of 2020 value has outperformed growth in the S&P 500, S&P 600 (small cap), S&P 400 (mid-cap), Russell 2000 (small cap), CRSP US Small Cap index (used by Vanguard) and EAFE (international developed). After four years of outperformance maybe it isn’t so much an emerging trend as a…trend. All of those value indexes have also outperformed the S&P 500 since the COVID nadir except EAFE. International returns are heavily influenced by the exchange rate though and once the dollar peaked in October of 2022, EAFE value outperformed all the others by a pretty good margin. A weaker dollar is another trend we expect to endure although it is currently oversold and due for a bounce.

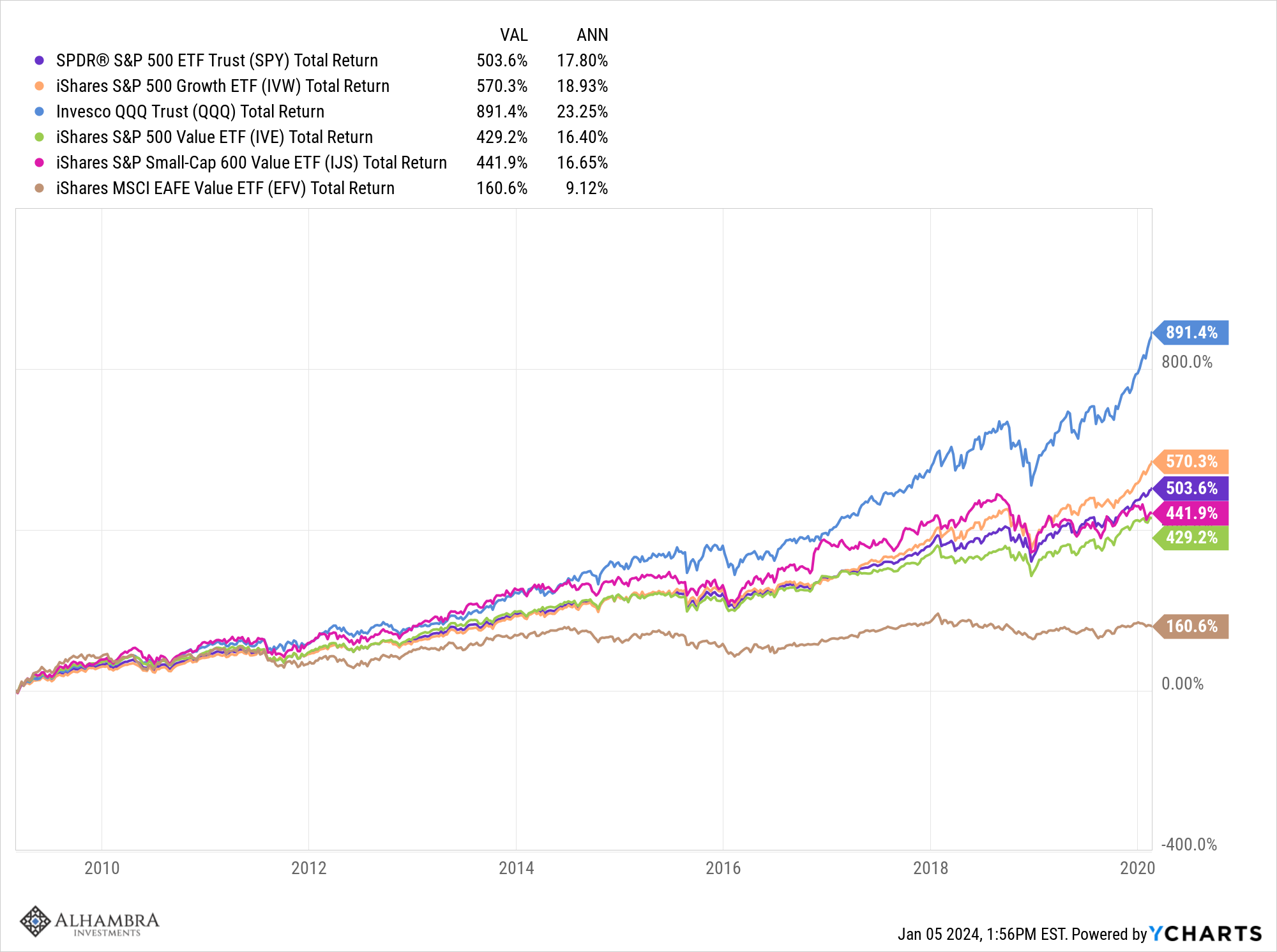

In the era of zero interest rates (ZIRP) and Quantitative Easing (QE), from the lows of the 2008 crisis in March 2009 to the peak in February 2020 at the onset of COVID, US growth stocks reigned supreme. The NASDAQ soared nearly 900% (23.25%/year) while the S&P 500 growth index only managed 570% (18.9%/year). The S&P 500 value index was no slouch at 429% (16.4%) but it is also now the highest priced of the above value indexes. Small and mid-cap value stocks performed well but not in comparison to large-cap growth. And international value, with the dollar rising for most of that time, was the poorest performing of them all, rising a fraction of the S&P 500 growth index.

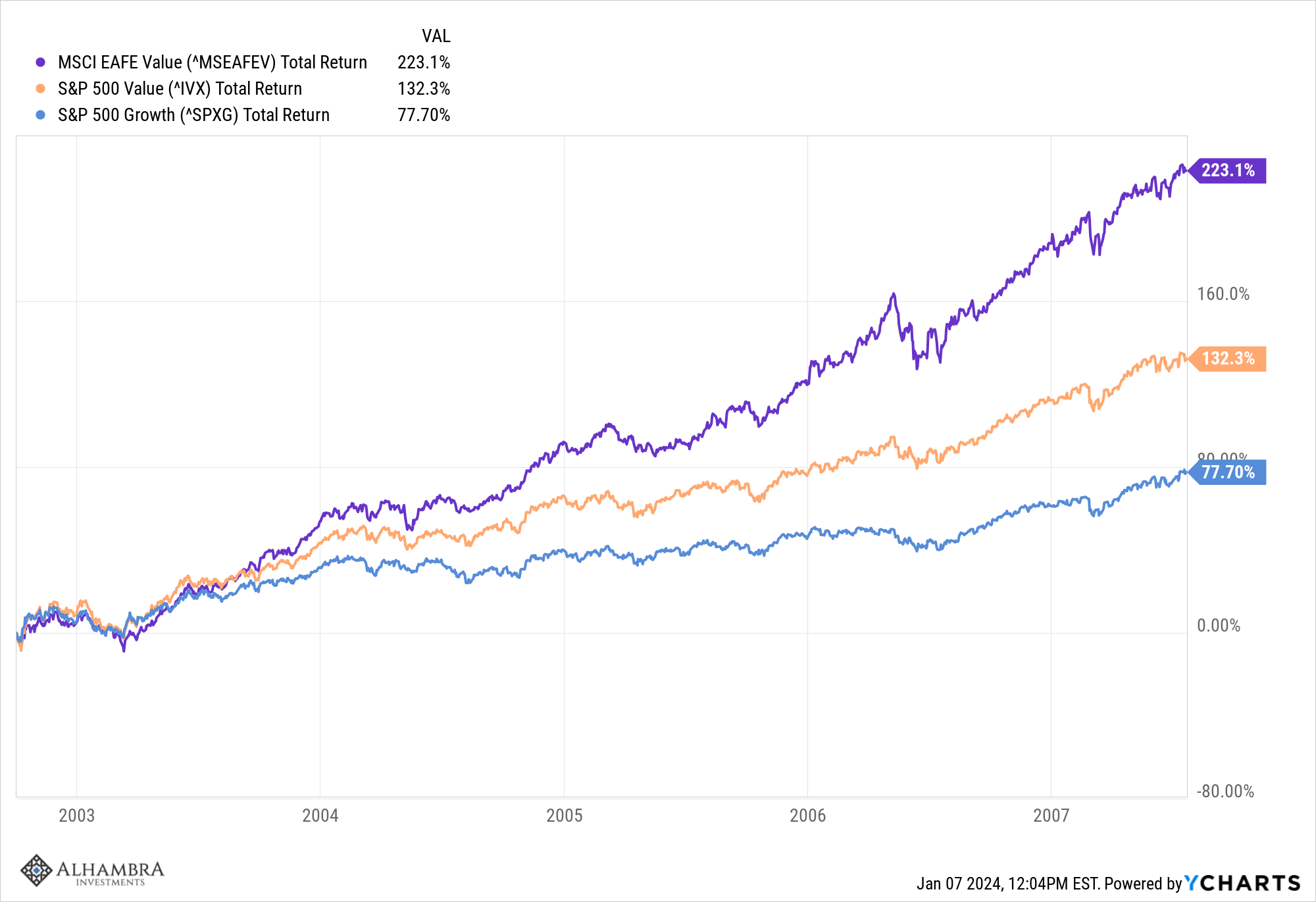

The outperformance of value or growth are trends that tend to last years. Before the post-COVID, growth-dominated period we had a five-year period of value outperformance with the S&P 500 value index nearly doubling the returns of the growth index. And in a weak dollar environment, EAFE value beat them both by a wide margin.

Getting this one decision right, favoring growth or value at the right time, can obviously pay enormous dividends for investors. This is the kind of trend we are trying to capture, long-term shifts that last five years or more. These trends are, to some degree, dictated by other trends like interest rates and the dollar but they are really dictated by attitudes. Value outperformance periods, which follow more speculative growth periods, tend to be more sober, more concentrated on real things. If growth outperformance periods are dominated by FOMO (Fear of Missing Out), value periods are marked by FOMU (Fear of Messing Up).

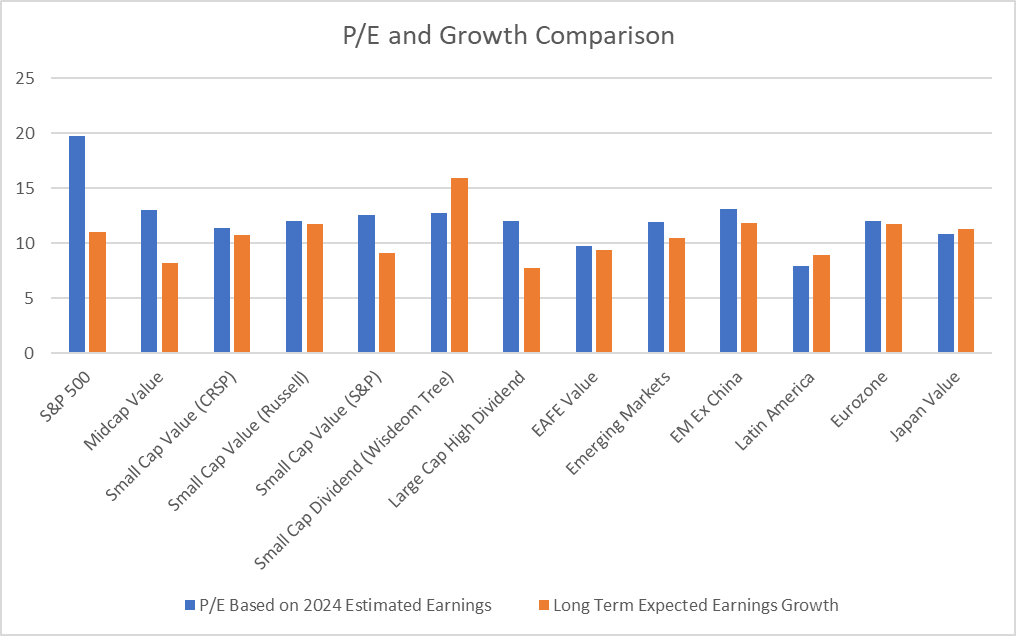

Where growth’s recent outperformance leaves us today is with large-cap stocks very highly valued and everything else much more reasonable. And within the small, mid, and international alternatives, value offers the best risk/reward:

If the long-term downtrend in interest rates that started in the early 80s is over – and I think it is – valuations overall seem likely to fall. The 10-year Treasury yield peaked in late 1981 at nearly 16% and started a fall that took it all the way to 0.5% in 2020. The Cyclically Adjusted PE (Shiller) for the S&P 500 hit its post-Great Depression low in August of 1982 at 6.64. By 2021 it was over 38, a level only exceeded by the dot com bubble in 1999 when it hit 44; today it is still over 30. It is not a coincidence that valuations rose as interest rates fell. Now, I don’t happen to think much of the Shiller P/E as a timing tool – and you shouldn’t either – but it does tell you about risk/reward. And I don’t think much of cap-weighted indexes either because they are essentially momentum strategies with the largest companies getting the highest weightings. In the S&P 500 the result is that 30% of the value of the index is in the top 10 names. So a high Shiller P/E doesn’t mean all the stocks in the index are overvalued. But the top 10 holdings, which dominate the index, are really expensive. The growth portion of the index is just an extreme version of the index as a whole. We made a decision, as a firm, to avoid the index for that reason in late 2021 and that hasn’t changed.

Breaking the long-term downtrend in rates doesn’t mean they are going to shoot back up to 16% anytime soon. There will be cyclical ups and downs but I think rates will generally be higher over the next decade than they were in the last. If that is true and valuations generally move lower, fundamentals are going to matter again. I think a lot of investors forgot – or never learned – what it means to be an investor in the ZIRP/QE period. Everything just became a chase for the next hot thing with ETFs for every imaginable theme (or meme). I think the NFT craze epitomizes this era of “investing” where things with no intrinsic value at all were bid to crazy heights. I am still astonished that anyone ever convinced themselves that a digital image of a badly drawn cartoon ape was worth more than a couple of bucks. But that’s what happens when money is essentially free. But as I said, I think that era is now over. It’s time to get back to the basics of investing in real companies with real earnings, cash flow, and dividends to prove it.

Joe Calhoun

Stay In Touch