The 10-year Treasury Note yield fell 13 basis points last week, a move that would not normally rate any mention whatsoever, but the path of that small decline does. From Monday to Thursday, the yield fell, from high to low, by 34 basis points, a move that added 1.3% to bond prices (Aggregate bond index) in four days. In a world where it takes a year to accumulate roughly 4% interest, that kind of move is significant. From Thursday’s low of 3.82%, the yield rose to 4.05% by Friday afternoon and closed at 4.03, a 21 basis point move in one day. The question is why? Why did we see such volatility in the bond market last week?

Well, there was an FOMC (Federal Reserve Open Market Committee) meeting last week and as I’ve pointed out numerous times in the past, the Fed’s policy of forward guidance has produced more, not less, volatility than in the past. The essential problem is that they create expectations regarding future policy based on their economic projections which have been almost comically wrong over the years. The Fed can’t predict the future any better than your local psychic, which wouldn’t be a problem if they had the same influence on the economy as the typical crystal ball gazer. But of course that isn’t the case. Or is it?

The focus for markets from the FOMC statement and Jerome Powell’s press conference was the future course of short-term interest rates. Would the Fed be cutting rates this year and if so, when and by how much? Powell wasn’t expected to say a lot about that, other than the standard “we’re data dependent” response, but he surprised markets by essentially saying that a cut in March was not anticipated. As soon as he said that, the stock market started to sell off and by the close was down 1.2%. Interestingly, bond yields didn’t move all that much but what move there was, was down. That would seem to indicate the market believed that not cutting in March would be a mistake, one that would lead to economic slowdown. How exactly anyone thinks they can know that right now is beyond my reckoning but that’s the clear implication.

People sold stocks and bought bonds because the odds of a rate cut in March fell during the press conference. Are there really people who believe that leaving short-term interest rates unchanged for the next few months will have a significant impact on economic growth? I mean we’re talking about a difference of 0.25% for four months (assuming the first cut comes in May instead). Is that really enough to change the course of the economy? Seriously?

During his press conference, Powell said:

Our restrictive stance of monetary policy is putting downward pressure on economic activity and inflation.

Earlier in the speech he offered scant evidence of that downward pressure:

GDP growth in the fourth quarter of last year came in at 3.3 percent. For 2023 as a whole, GDP expanded at 3.1 percent, bolstered by strong consumer demand as well as improving supply conditions. Activity in the housing sector was subdued over the past year, largely reflecting high mortgage rates. High interest rates also appear to have been weighing on business fixed investment.

Housing has added to real GDP growth for two quarters in a row and fixed investment for four. It is true that housing was “sluggish” last year with higher mortgage rates but most of that was in existing home sales which don’t have a large impact on economic growth. New construction is where GDP is most impacted and on that front, the Fed’s rate hikes didn’t accomplish much. Housing starts were up 7.6% over the last year, permits were up 6.1% and new home sales rose 4.4%. Ironically, if the Fed hadn’t raised rates so far, new construction and home sales may have been lower as there would have been more availability of existing homes with lower rates. As for fixed investment, I suppose it is possible that investment would have been higher with lower rates but the second biggest negative on the investment side last year was…inventories, which had nothing to do with Fed policy and everything to do with the supply chain hangover from COVID. Residential investment was the biggest negative in fixed investment but that essentially ended three quarters ago and was more than offset by non-residential. So, where exactly is the impact of the Fed’s higher short-term interest rates?

If the Fed raised short-term interest rates by 5.25% over roughly 18 months and had almost no impact on the economy, why would not lowering rates by 0.25% have any impact at all?

The Fed doesn’t know any more about the economy than the private sector. Jerome Powell makes that clear in the question and answer period. When asked what it would take for the Fed to have greater confidence that inflation is on a sustainable lower path he said:

So we have six months of good inflation data. The question really is: That six month of good inflation data, is it sending us a true signal that we are, in fact, on a path—a sustainable path down to 2 percent inflation? That’s the question. And the answer will come from some more data that’s also good data.

The Fed doesn’t know if inflation has peaked or whether this is just a lull before another wave higher. And neither does anyone else. They have the same information everyone else has. In answer to one question, he mentioned that they consult a variety of Taylor rules in considering whether to move rates. Taylor rules are formulas for setting the Fed Funds rate, the original of which was developed by John Taylor at Stanford. Want to see what Powell’s looking at? Here you go: Atlanta Fed Taylor Rule Utility and Cleveland Fed Simple Monetary Rules. And it wasn’t exactly obscure before these were posted on various Fed websites. Google it and you’ll get more information than you ever wanted. The Fed decision makers are looking at the same things we are and trying to figure out what’s going on. In fact, Jerome Powell is using the same language about the economy that I’ve been using for two years.

…the economy has, largely, reopened and is broadly normalizing, as you see.

I think the labor market by many measures is at or nearing normal, but not totally back to normal.

The economy is broadly normalizing…

But we do expect that it will moderate as supply chain and labor market normalization runs its course…

…if you’re normalizing policy, you might be reducing rates but continuing to run off the balance sheet. In both cases, that’s normalization

I think we’re basically in the throes of getting through the pandemic economy

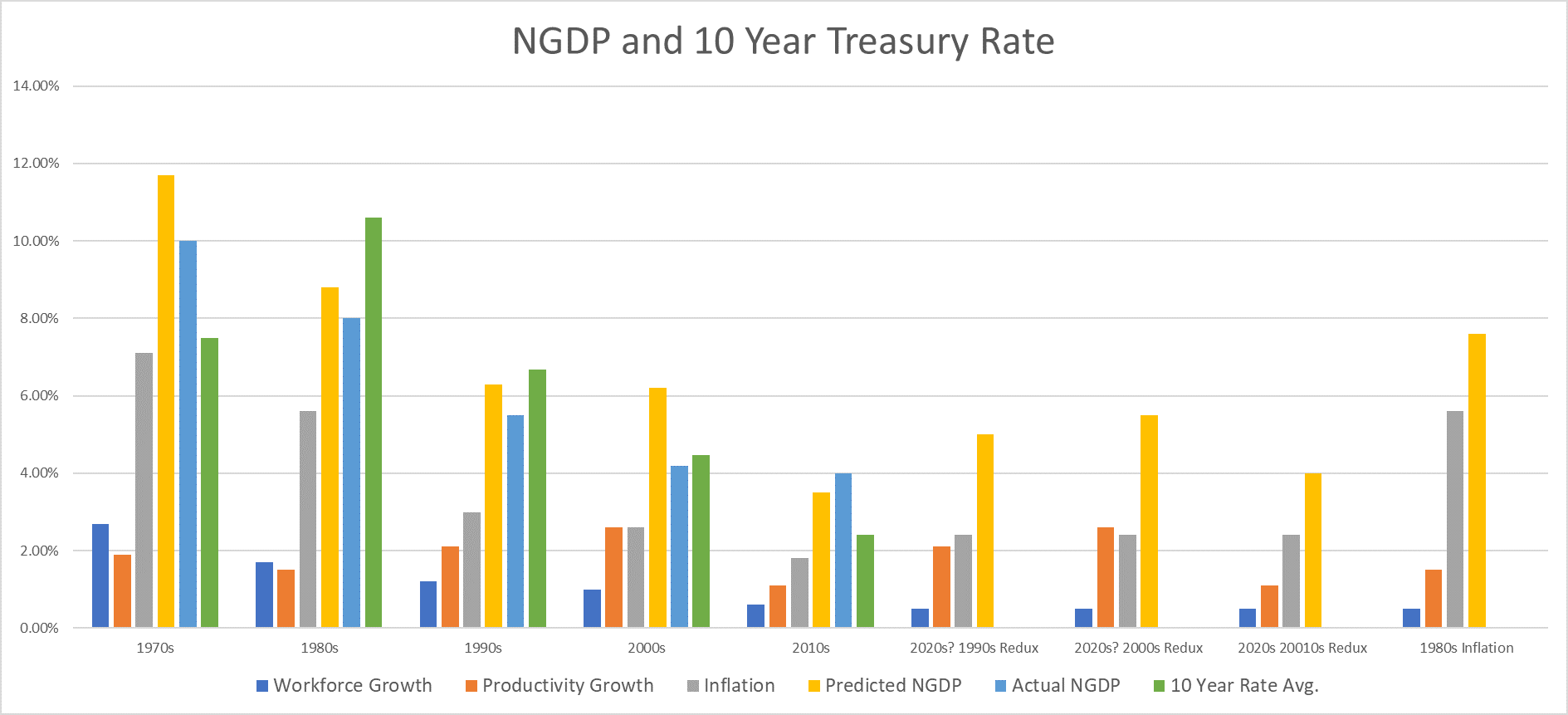

If you’ve been reading these weekly commentaries for any length of time, you know that’s been our theme almost since the onset of COVID, getting back to “normal”, in policy, in interest rates, and in economic growth. And I’ve taken pains to point out that the yield on the 10-year Treasury note right now is right at the average since 1990 – this is normal, not the zero interest rate world of the post-2008 period. The question though is whether we will stay in this current zone of normality. I don’t know the answer to that but I laid out what to watch for in a video last October about Nominal GDP and interest rates. In that video, I talked about what our future economic growth would look like based on what kind of productivity growth we get from our changed post-COVID economy. If we get productivity like we had in the period from 1990 to 2010, we’ll likely have NGDP growth of 5 to 5.5%. If we get productivity growth like we had in the 2010s, we’ll see NGDP growth of 4% and if you get a rerun of the 1980s, NGDP would grow upwards of 7%. With higher productivity comes higher nominal growth, higher real growth, and lower inflation. Higher nominal growth without higher productivity growth yields less real growth and more inflation.

I don’t know what productivity growth will be in the future. That depends on investment and innovation that I can’t predict. Neither can Jerome Powell or anyone else at the Fed; they’re struggling with the same questions. Here’s Powell in the press conference:

I think we’re basically in the throes of getting through the pandemic economy. And the question will be, what is it that has changed? You know, productivity tends to be based on, you know, fundamental aspects of our economy.

Is there—is there a case—will it be the case that we come out of this more productive, more—on a sustained basis? And I don’t know. I don’t know. What would it take? It would take—you know, people talk about AI, but I would—my guess is that we may shake out and be back where we were because I don’t — I’m not sure I see—work from home doesn’t seem like it’s a big productivity increaser. AI—artificial intelligence, generative—may be, but probably not in the short run; probably maybe in the longer run. So I’m not—I’m not seeing why it would, but you know, right—you know, right now I would say that productivity is kind of what falls out of the broader forces that are driving people in and out of the labor force, and activity returning, and supply chains getting fixed.

If you’ve been sitting around waiting to hear the next utterance from Jay Powell or any other member of the Federal Reserve, you’re wasting your time. I’ll let you in on a little secret. While everyone in the investment business was glued to their TV listening to Jerome Powell’s every word, my TV was turned off and I was working on something unrelated to the economic outlook. I read the transcript the next day in the Wall Street Journal. I already knew what the FOMC would do and I knew mostly what Powell was likely to say. It was just common sense and I had more important things to do. I’m certain you do too. So, stop waiting with bated breath for the next statement from the FOMC and start thinking for yourself (or just keep reading these weekly commentaries!).

There were any number of things that might have moved interest rates last week because traders respond to every new piece of information. Indeed, today, it seems they overreact to every new piece of information. But, as Albert Einstein said, information is not knowledge. Another announcement last week, the quarterly refunding announcement from the Treasury, was as anticipated as the FOMC statement and just about as important, which is to say, not very. In the QRA the Treasury provides information about how they will raise the necessary funds from the market to finance the government over the coming quarter. There are people who believe they can gain some kind of advantage from this information and that might be true if they got it before everyone else. Otherwise, any advantage is based on what? Reading speed? Besides, I told you last week to expect the Treasury to announce they would be selling a lot of TBills. And when I finally got around to reading the press release at the end of the week, that’s exactly what I found.

You aren’t going to gain any insight into the economy or markets by watching Jerome Powell’s press conference (or his interview on 60 Minutes tonight) or reading every detail of the QRA. You gain insight by thinking for yourself, something that seems almost quaint today. Don’t wait for someone else to tell you what you should think, about markets or the economy or anything else. There are a range of possibilities that includes a lot that no one will see coming but we all have the same information. It is up to us to turn it into knowledge.

I don’t know what the future holds. I am, like Jerome Powell, looking at a range of things, from immigration and demographics to trade and industrial policy to AI to work from home to gene editing to MRNA technology and trying to figure out if any of it adds up to better economic growth and less inflation. I am very pessimistic about immigration and trade, where restrictions on both are likely to lead to less growth and higher inflation. I am encouraged by technological developments although I am skeptical that AI is the big answer everyone seems to think. Call me skeptically optimistic.

Joe Calhoun

Environment

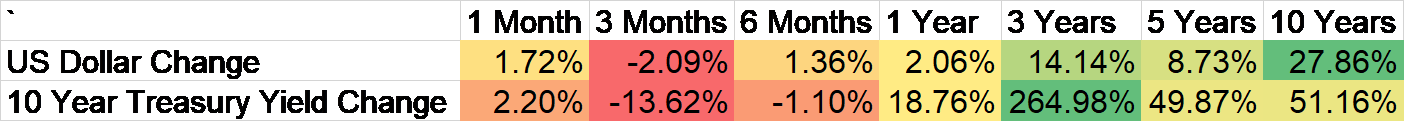

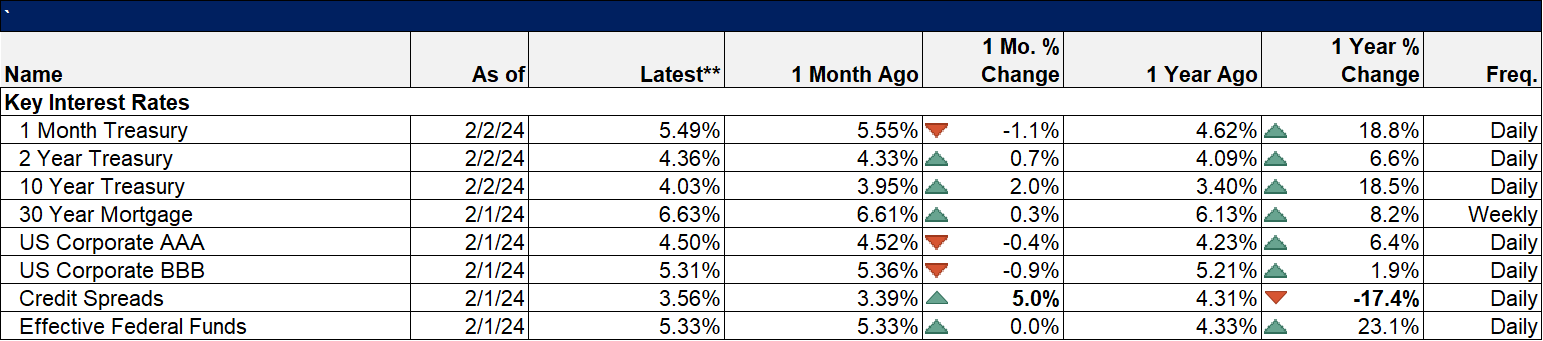

The environment is…in flux. There’s almost no change in rates or the dollar over the last six months and for the dollar the last year. The 10-year yield is in a short-term downtrend and barely hanging on to the uptrend that started in late 2021.

The dollar is in a short-term downtrend but it isn’t of much significance; call it neutral if you want. The long-term uptrend that started in 2011 remains intact.

Markets

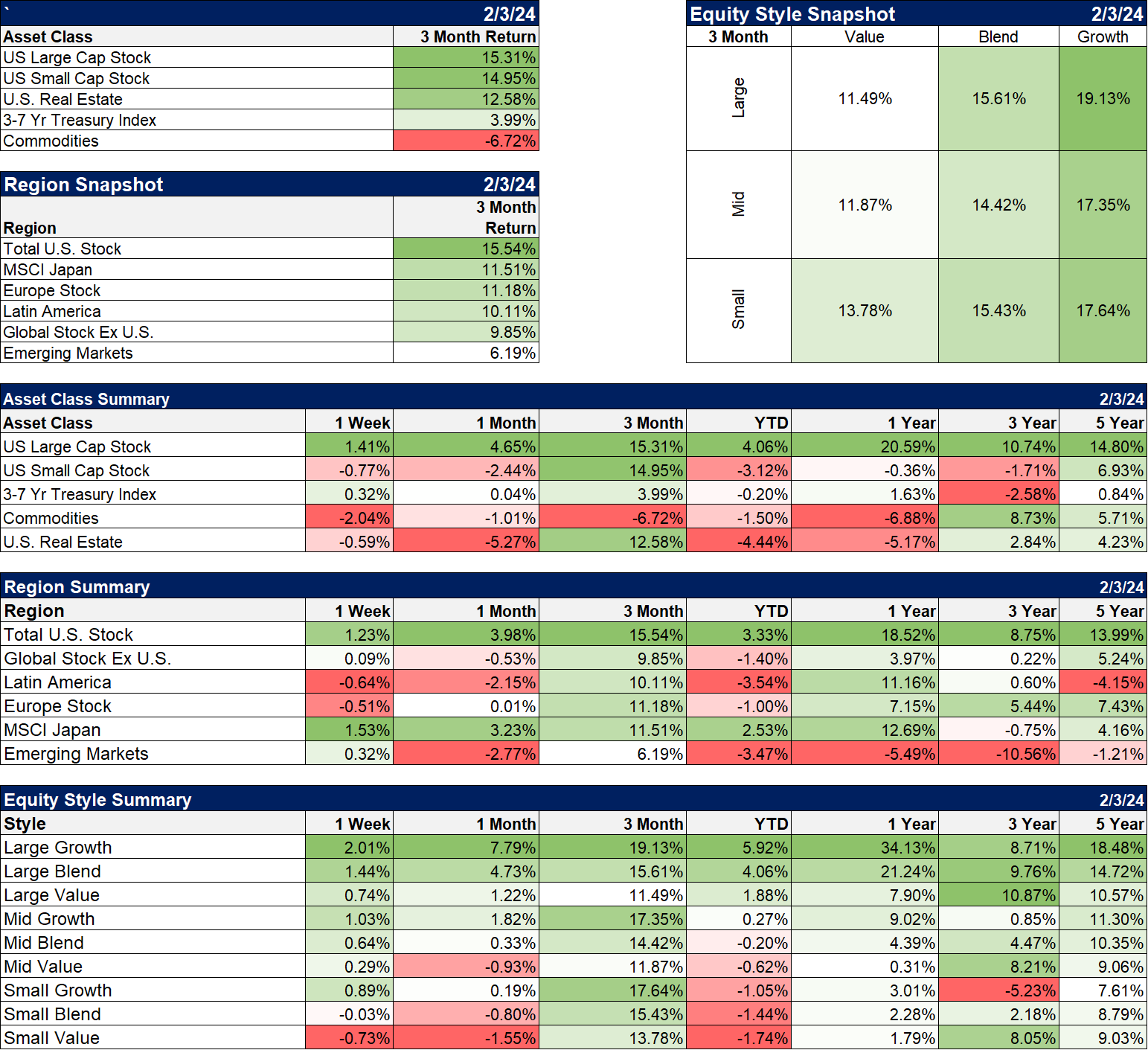

Markets year to date are all about large-cap growth stocks. All the other major asset classes we follow for our portfolios are down on the year. Thinking longer term, the three-year numbers continue to favor value stocks, large and small. Real estate has given back some of late last year’s gains but that is not unusual after such a big run in a short period of time. Interestingly, last week when everyone was worried about regional banks because of commercial real estate – for the record, I’m not – REITs were down a fraction of a percent.

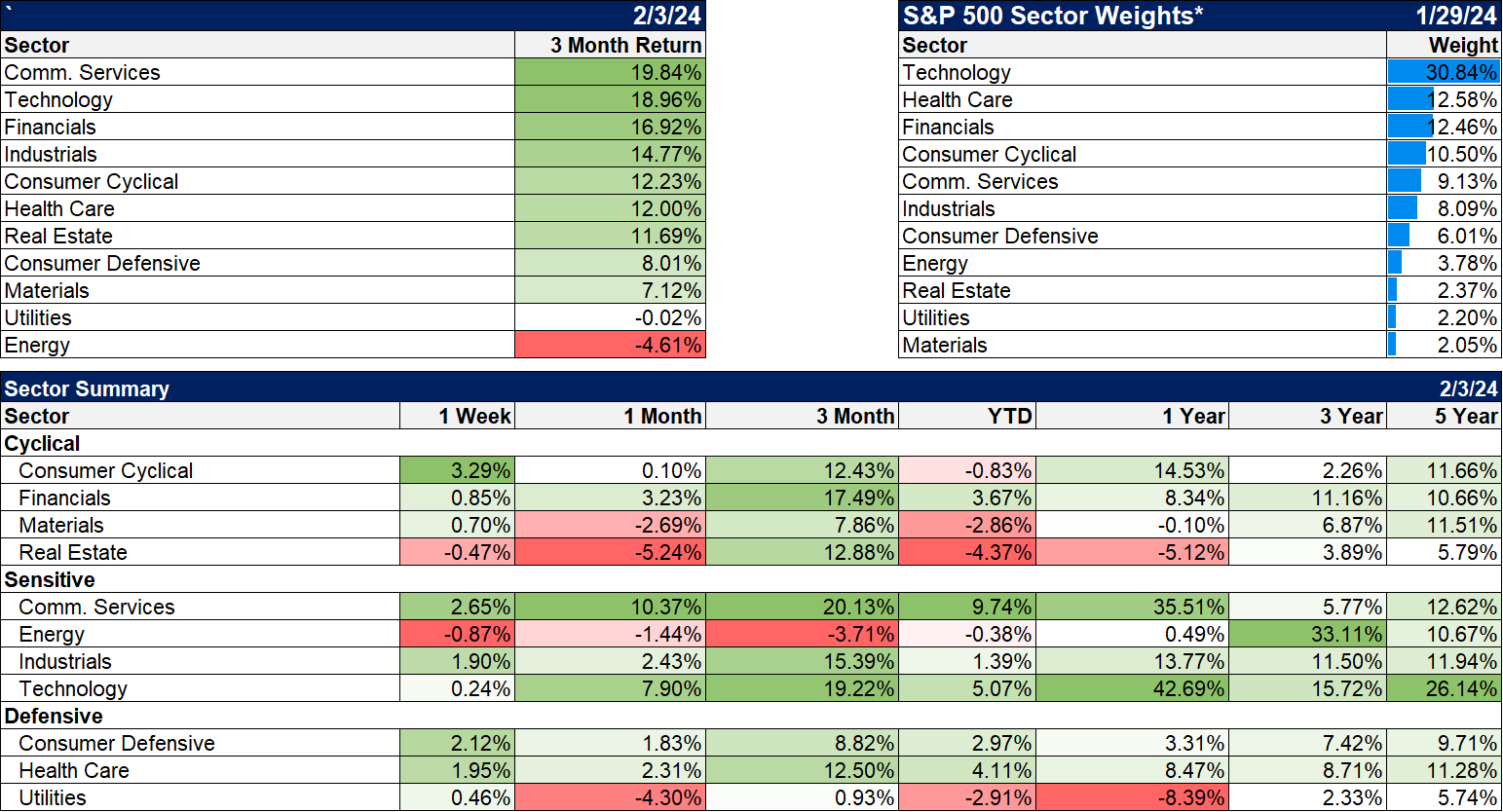

Sectors

The big sector winners last week were communication services, on the back of a huge gain in Meta, nee Facebook, consumer defensive (and healthcare which is generally defensive), and consumer cyclical. If you can find a theme there, please let me know.

Market/Economic Indicators

Some economic news from last week that was overlooked because everyone was focused on the Fed and the payroll report (which is subject to large revisions and means next to nothing on first release):

- S&P Case Shiller home prices were down 0.2% month to month in November (the data lags a lot). A moderation in home prices would be very positive for future inflation.

- Consumer Confidence rose from 108 in December to 114.8 in January

- The employment cost index rose less than expected, up 0.9% in Q4

- Non-farm productivity rose 3.2% in Q4 and unit labor costs rose just 0.5%

- S&P manufacturing PMI rose back to expansion in January at 50.7 versus 47.9 in December

- ISM manufacturing index rose to 49.1 in January versus 47.1 in December and expectations for a decline

- ISM manufacturing new orders rose to 52.5 in January versus 47 in December. That’s the first reading above 50 (indicating expansion) since August of 2022.

- Construction spending rose 0.9% in December

- University of Michigan consumer sentiment rose to 79 and inflation expectations fell under 3%.

Here are some long-term trends that are pretty encouraging:

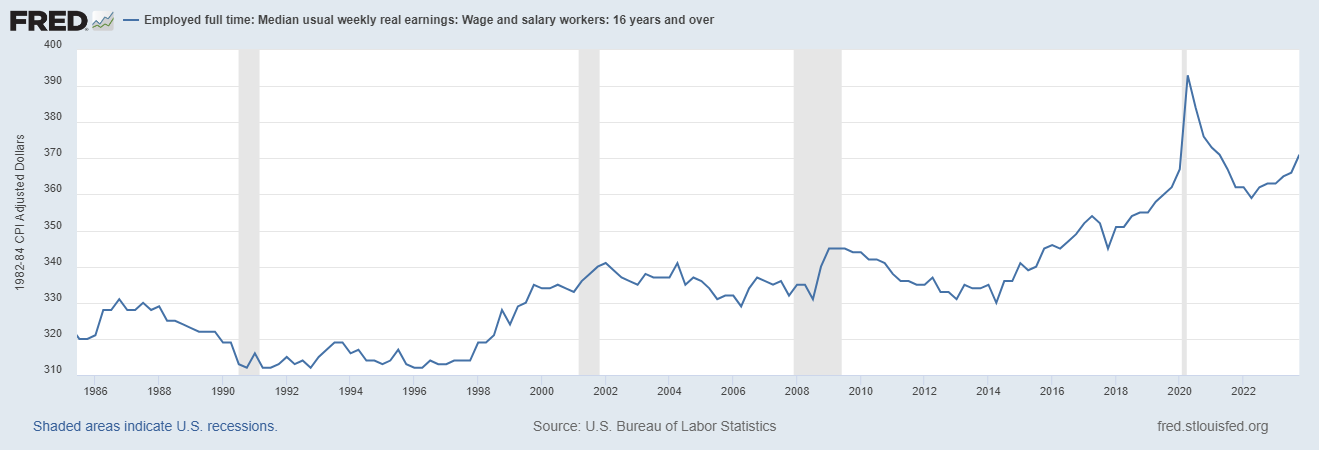

Real (inflation-adjusted) weekly earnings are rising at a healthy pace

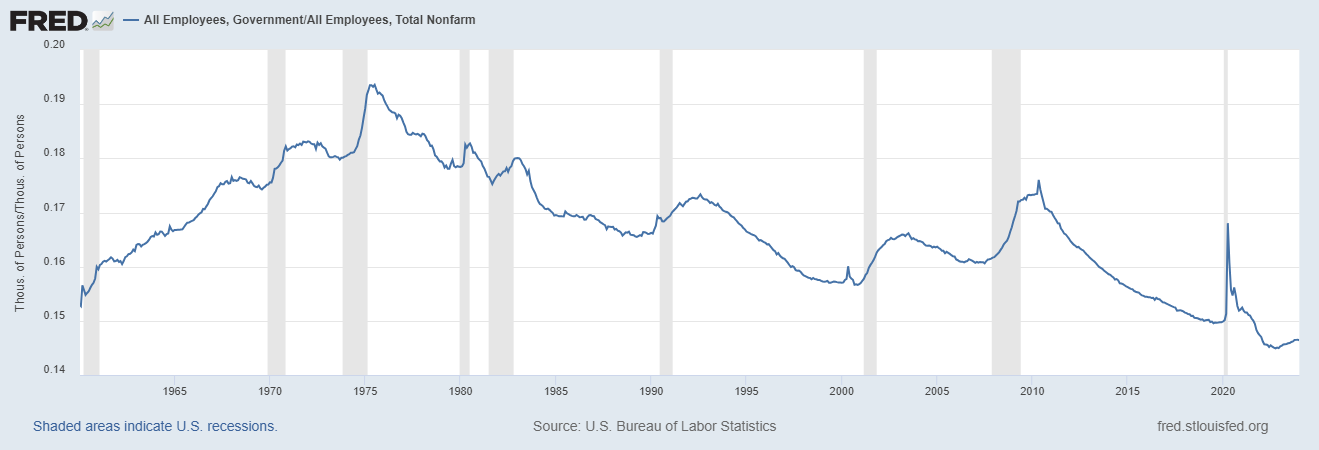

Government employees as a percent of the total is lower than at any time since the 1960s

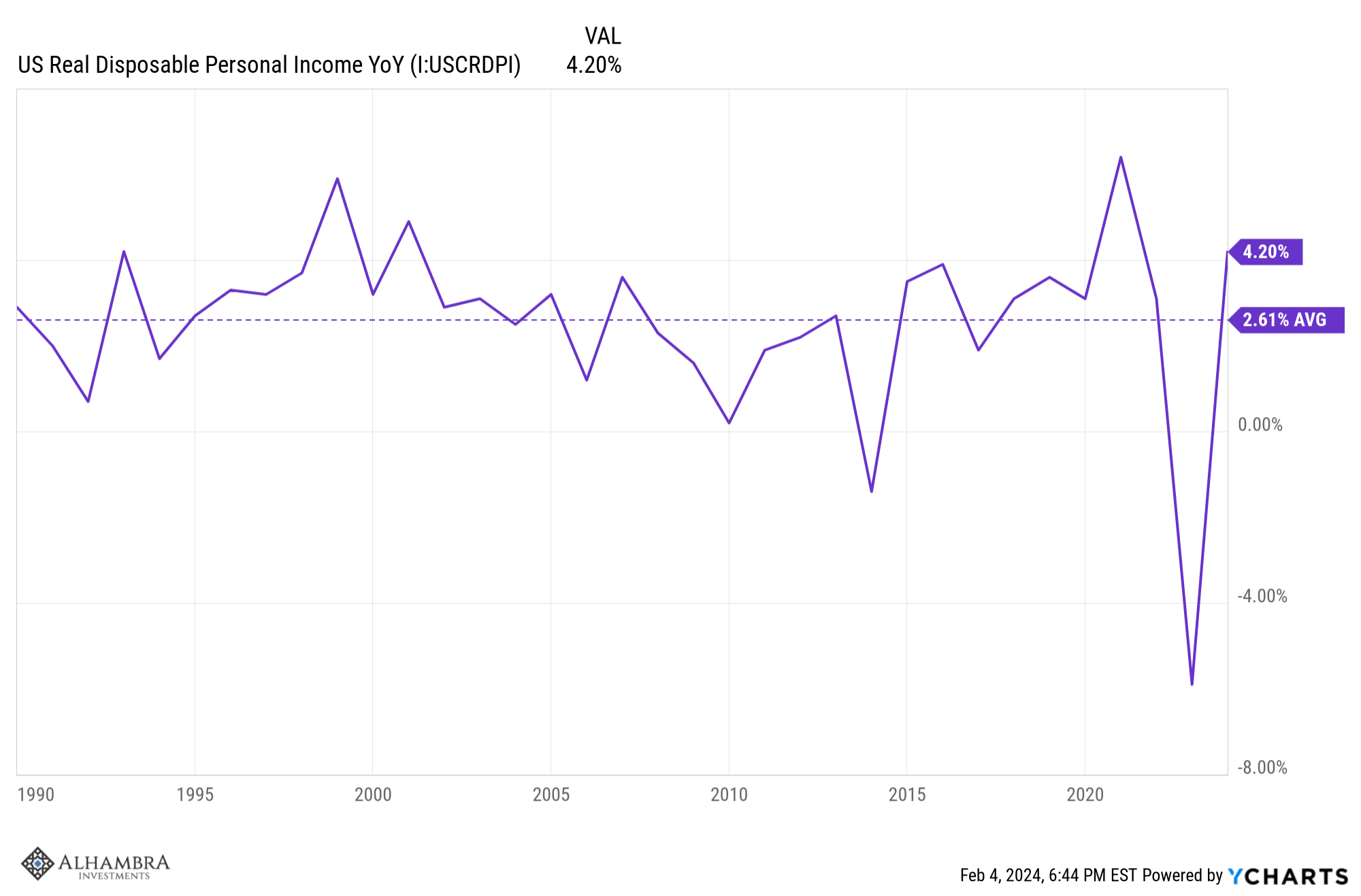

Real disposable personal income is rising at a rate considerably higher than the average since 1990

Stay In Touch