Special Note: I’m in Miami this week, a mix of business and personal. I lived here for 30 years and we raised our family here but we moved to South Carolina a little over 3 years ago because we were tired of the traffic and, more than that, the irritability that comes with so many people crammed into such a small space. This is my second trip here since we left and let’s just say it hasn’t gotten less crowded. It is still the most unique city in America, in my opinion, and I still love the mix of cultures but it can test your patience.

This morning I searched for a place to go to breakfast and Yelp had one place for breakfast/brunch that had 5 stars – Our Grounds:

We are a non-profit corporation that runs a coffee shop in a facility that provides vocational training, education and employment opportunities to adults with intellectual and cognitive disabilities.

It is a small cafe with wonderful, fresh food and friendly service. But what struck me more than anything was how happy everyone was, staff and customers. Literally everyone there wore a smile.

I think sometimes we get caught up in the conflicts in our country, the differences we have about politics and culture. But I was reminded this morning that we are a country of great compassion, kindness, and grace and when we come together we can accomplish great things. Organizations like Our Grounds make a difference every day, in every state, in every community and they deserve our support.

If you are in Miami, go to Our Grounds and have a meal. If you aren’t, click on that link above and make a donation. It’ll put a smile on your face too. I got it started by doing both this morning.

Last I checked we have over 10,000 smart, caring people on our weekly email list and I’m happy to highlight other worthy organizations in future letters. If you know of a non-profit that deserves our support, send me an email: jyc3@alhambrapartners.com.

Joe Calhoun

Commentary

But where do we draw the line on what prices matter? Certainly prices of goods and services now being produced–our basic measure of inflation–matter. But what about futures prices or more importantly prices of claims on future goods and services, like equities, real estate, or other earning assets? Are stability of these prices essential to the stability of the economy?

Clearly, sustained low inflation implies less uncertainty about the future, and lower risk premiums imply higher prices of stocks and other earning assets. We can see that in the inverse relationship exhibited by price/earnings ratios and the rate of inflation in the past. But how do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values, which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions as they have in Japan over the past decade?

– Alan Greenspan, The Challenge of Central Banking In A Democratic Society

There’s been a lot of talk about bubbles recently as the S&P 500 scales new heights. I have never liked that term since there is no way to know the future, to know that what is happening today is indeed “irrational” whether in the form of excessive exuberance or gloom. We only know it was irrational with the benefit of hindsight.

Alan Greenspan’s speech about Central Banking In A Democratic Society would not be remembered today except for that phrase “irrational exuberance”. For most people it is a boring speech about the evolution of money and central banking in America, starting with a reference to William Jennings Bryan’s famous speech about the gold standard:

If they dare to come out in the open field and defend the gold standard as a good thing, we shall fight them to the uttermost, having behind us the producing masses of the nation and the world. Having behind us the commercial interests and the laboring interests and all the toiling masses, we shall answer their demands for a gold standard by saying to them, you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.

What Bryan was advocating was an abandonment of the gold standard in favor of bimetallism. He wanted to monetize silver at an above market price to expand the money supply and allow farmers to more easily pay off their debts. This came at the peak of what is known in economic history as the long depression, the period of deflation that followed the Civil War as the US returned to the gold standard. What Bryan wanted was inflation to relieve the burden of debts on the “common man”.

It isn’t an exact parallel but in a way, one could say that we faced a similar situation after the financial crisis of 2008. It isn’t coincidence that Bryan was what we know today as a populist and that both parties today offer only slightly different versions of supposedly populist economic platforms. The decade after 2008 leading up to COVID in 2020, was one marked by consistently low inflation and near zero interest rates. It was also a time when inequality became a much more prominent topic of discussion as ZIRP and QE were seen as benefitting the wealthy, whose balance sheets were positively impacted by rising asset prices, as Greenspan accurately predicted.

COVID changed the equation as the government and central bank response changed the composition of household balance sheets. Essentially, debt was shifted from household balance sheets to the government’s. Households today are still holding much more cash – over 15% of GDP – in checking accounts than prior to COVID and household net worth is at an all-time high. And that is not just true of high income households; the bottom 50% of the income distribution is still holding a lot more cash too. And while inflation has been seen as a problem, especially by lower income households, it too had a positive impact on many American household balance sheets in the form of rapidly rising house prices.

If anything, I think the official inflation rate failed to fully capture the rise in prices of recent years. My visit to Miami brought that into sharp focus this week. For middle class families that owned a house before COVID, the inflation was a boon. My own case is illustrative. The price of our modest home in the south Miami-Dade county rose by about 75% in the 18 months after the onset of COVID and it has continued to climb, now double the pre-COVID price. I benefitted from selling that house at an inflated price and moving to a state where real estate was cheaper. I got more house for less money and I wasn’t the only one.

Prior to COVID, a lot of baby boomers were facing a retirement that was underfunded and in a very real sense COVID bailed them out by raising the price of their existing house and allowing to cash out, move somewhere cheaper and retire. That’s a big reason why the labor force participation rate for the over 65 cohort fell from 26% to 23% after COVID – and stayed there – and I suspect it isn’t going up anytime soon.

The change in household balance sheets has also impacted other asset prices. More people have been able to invest in stocks and other assets because COVID gave them the wherewithal to do so. The number of brokerage accounts grew by 10 million in 2020 alone and has continued to grow. Now, some of what these new “investors” have done with their new found investment capital might be more properly classified as gambling – some of it literally – but a lot of it has ended up in index funds and other more traditional assets. Prices have responded accordingly.

The question we face today is, in many ways, the same one Greenspan posed nearly 3 decades ago:

…How do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values, which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions…

I think Jerome Powell has answered that question from the viewpoint of monetary policy. After last week’s FOMC meeting Powell said:

We believe that our policy rate is likely at its peak for this tightening cycle and that, if the economy

evolves broadly as expected, it will likely be appropriate to begin dialing back policy restraint at some point this year.

That doesn’t sound like a man worried about irrational exuberance to me. He also sounded a lot like Alan Greenspan in talking about future monetary policy:

We know that reducing policy restraint too soon or too much could result in a reversal of the progress we have seen on inflation and ultimately require even tighter policy to get inflation back to 2 percent. At the same time, reducing policy restraint too late or too little could unduly weaken economic activity and employment.

That passage could have been directly lifted from Greenspan’s speech 28 years ago. Notice too that Powell says “if the economy evolves as expected” and that they don’t know if it will. So, just as Greenspan noted, the Fed has to be pre-emptive, to change policy in advance of changes in the economy that are hard to predict. The conduct of monetary policy has changed some since Greenspan’s speech but not much.

So, to get back to the topic we started with, is the stock market in a bubble? I don’t know of course, but I would point out that the economy has been a lot better than most have expected and that flows directly through to corporate earnings and impacts stock prices. Earnings estimates for the S&P 500 for 2024 are about 12.5% above 2023 which might seem a bit low considering the index is trading for over 20 times those earnings. But markets are forward looking and not just by a few months; Q4 2024 earnings are expected to rise 20% above Q4 2023. And full year estimates for mid-cap (+20%) and small cap (+30%) are even rosier.

If those estimates are accurate, current stock prices don’t seem outrageous at all. Large caps are the most expensive and paying 21 times earnings for 12.5% earnings growth does seem a bit rich. But paying roughly 15 times earnings for 20% or 30% earnings growth doesn’t sound unreasonable at all. Of course, earnings estimates are notoriously inaccurate, especially at turning points, so you can’t count those chickens just yet. Accurate earnings estimates are ultimately a function of accurate economic forecasts.

One thing Alan Greenspan said in that speech so long ago that strikes a chord with me is when he describes how the Fed monitors the economy:

For many years, the Federal Reserve has maintained what we trust is a highly sophisticated day-by-day, near real-time, evaluation of the American economy and, where relevant, of foreign economies as well.

There is, regrettably, no simple model of the American economy that can effectively explain the levels of output, employment, and inflation. In principle, there may be some unbelievably complex set of equations that does that. But we have not been able to find them, and do not believe anyone else has either.

Consequently, we are led, of necessity, to employ ad hoc partial models and intensive informative analysis to aid in evaluating economic developments and implementing policy. There is no alternative to this, though we continuously seek to enhance our knowledge to match the ever growing complexity of the world economy.

I have said for many years that we cannot predict the future economy, that the best we can do is describe its present state. It isn’t as easy as it sounds because economic data is subject to revision; it is rarely an accurate representation of the economy when it is first released. Which means we are in the same boat as the Federal Reserve and their 400 PhD economists. We have to make investment decisions in advance of changes in the economy using forecasts that may or may not be accurate.

At some point in the next year, the stock market will probably have a correction, a drawdown of at least 10% but less than 20%. We get those, on average, about every 18 months. We had one of last year from July to October that was about 11% peak to trough. The next one, like all the ones before it, will happen because either the estimate of future inflation or economic growth embedded in stock prices at the time is deemed sufficiently wrong to produce that size of an adjustment in the outlook for earnings or the rate at which they are discounted. Smaller errors will produce smaller adjustments.

So far this year, the adjustments to the outlook have all been positive. Economic growth is surprising – again – to the upside which bolsters the outlook for earnings and inflation continues to moderate which should allow for a reduction in the discount rate. Those are positive developments and one would expect stock prices to rise in response. I hesitate to write this but call it….rational exuberance.

Environment

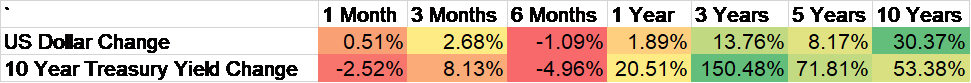

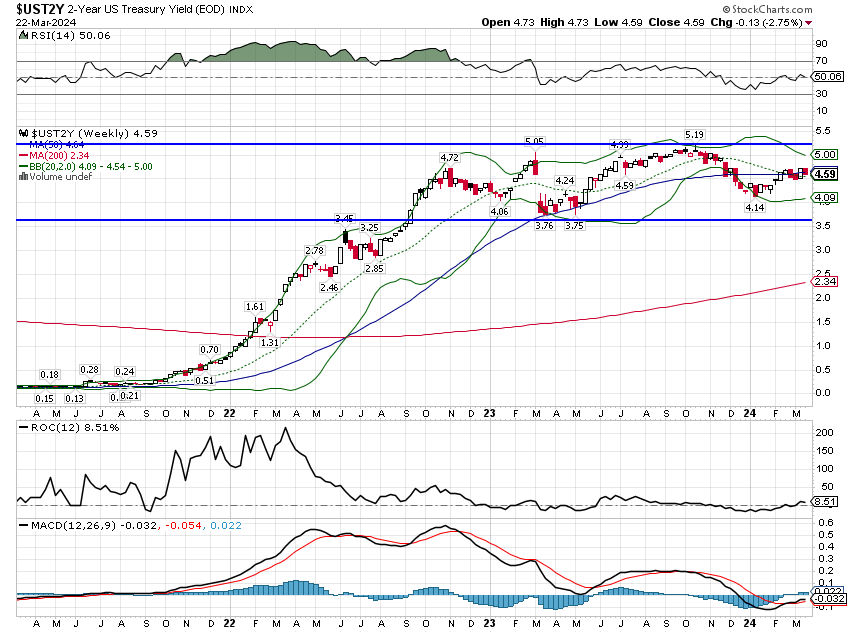

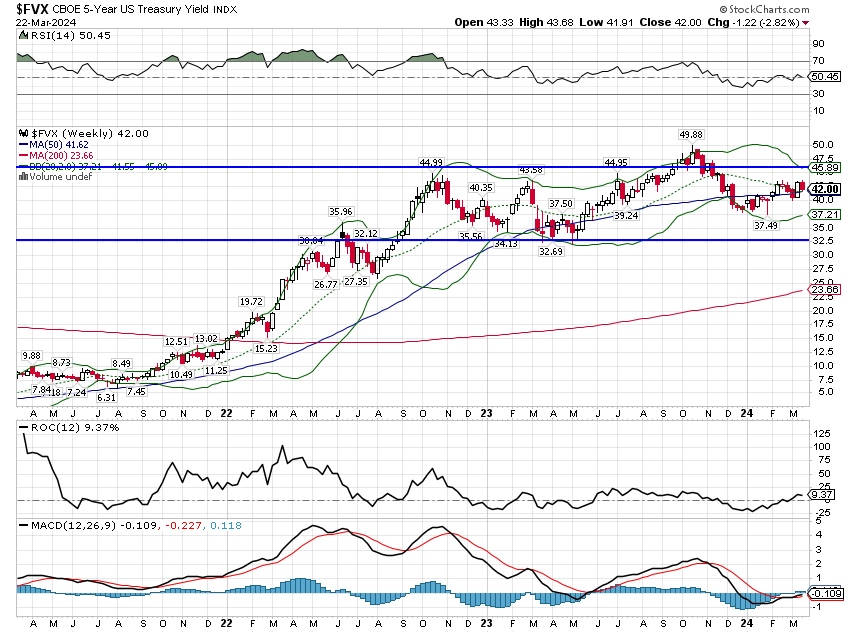

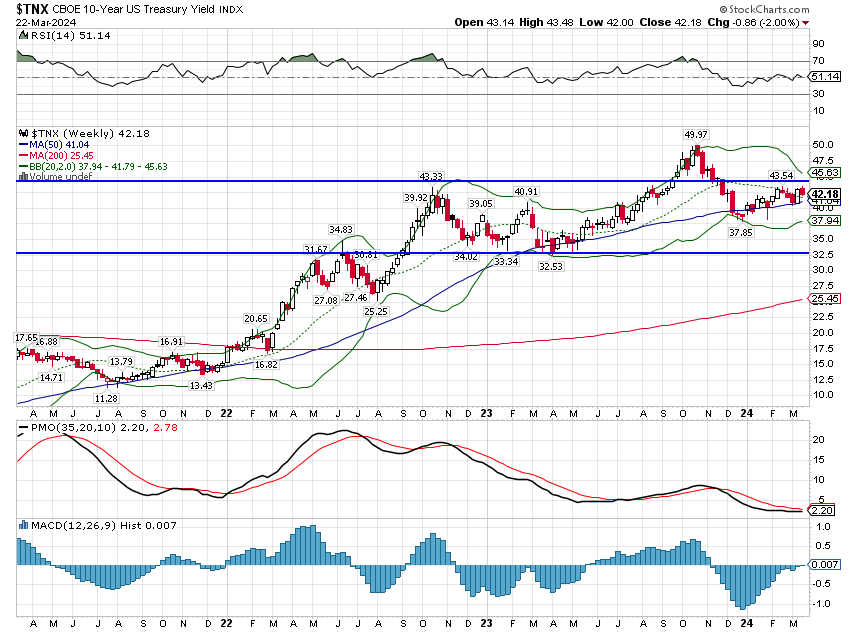

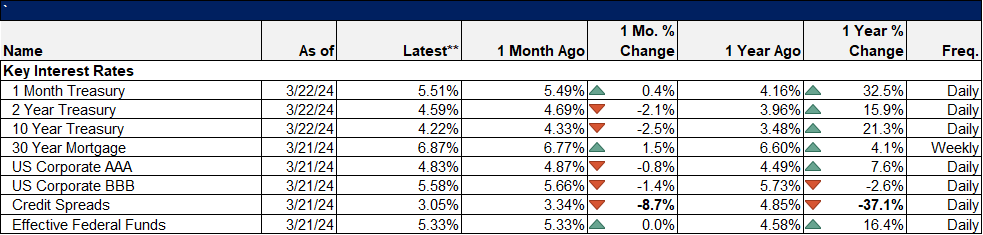

The trend of interest rates hasn’t changed with the 2-year, 5-year and 10-year Treasury yields continuing to trade in a range that has persisted for most of the last 18 months.

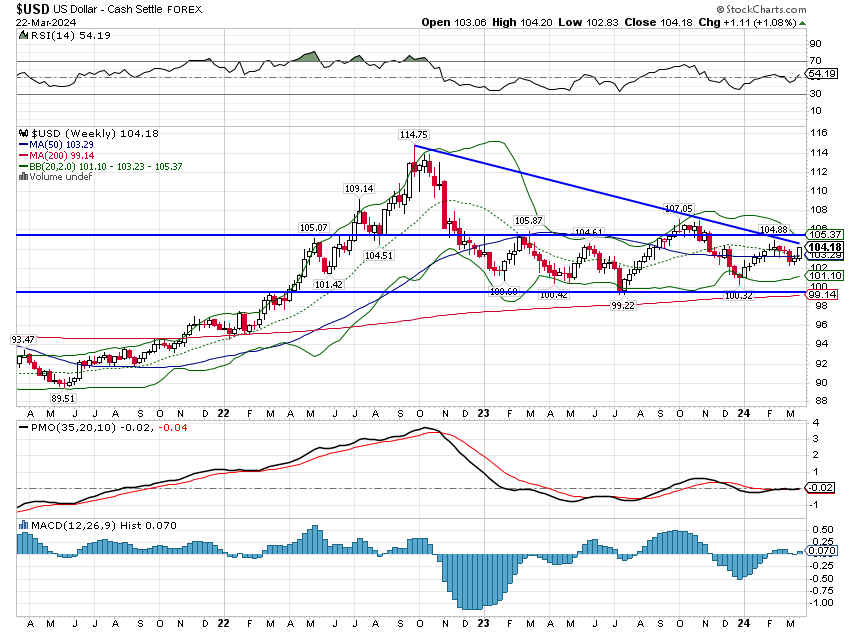

The dollar was up a little more than 1% last week and the short-term trend is on the cusp of changing. I wrote a few weeks ago about the DXY resuming its downtrend but that may have been premature. Like everyone else I have my own biases and a weak dollar is what I expect so I have to guard against seeing what I want to see. The short-term trend is still down in my opinion, but one could also see it like interest rates – in a trading range for over a year. Having said that, US economic data continues to show strength so we shouldn’t be surprised if the dollar breaks higher. Ironically, if it does, that would tend to suppress inflation and would make rate cuts more likely.

Markets

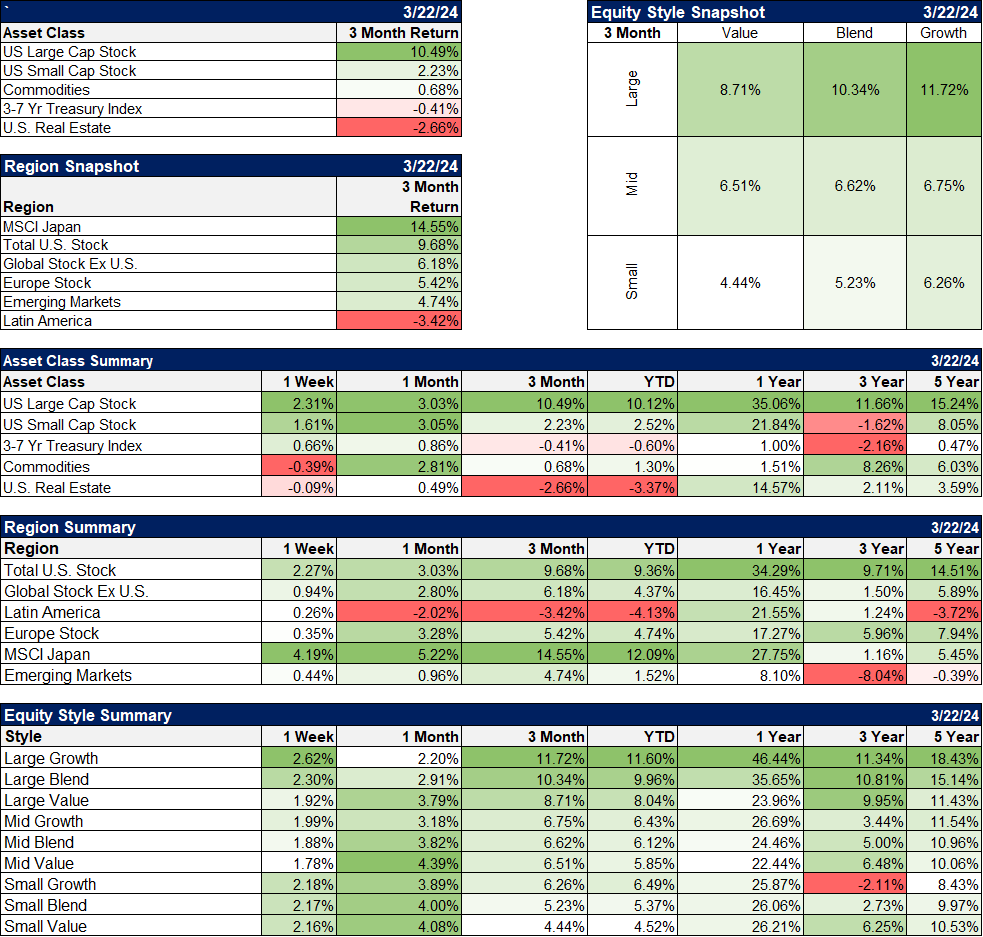

Stocks, large and small, had a good week as bonds rallied in the wake of the FOMC meeting. Commodities were basically flat as crude oil was flat and nat gas rose nearly 10% (but from a very weak level). Economically sensitive metals (copper, platinum, etc.) were lower but modestly.

Japan led foreign markets even as the BOJ ended negative rates and yield curve control. There was widespread anticipation of the move and an expectation that the Yen would rally on the news but anything that anticipated is unlikely to move markets; it was already priced in.

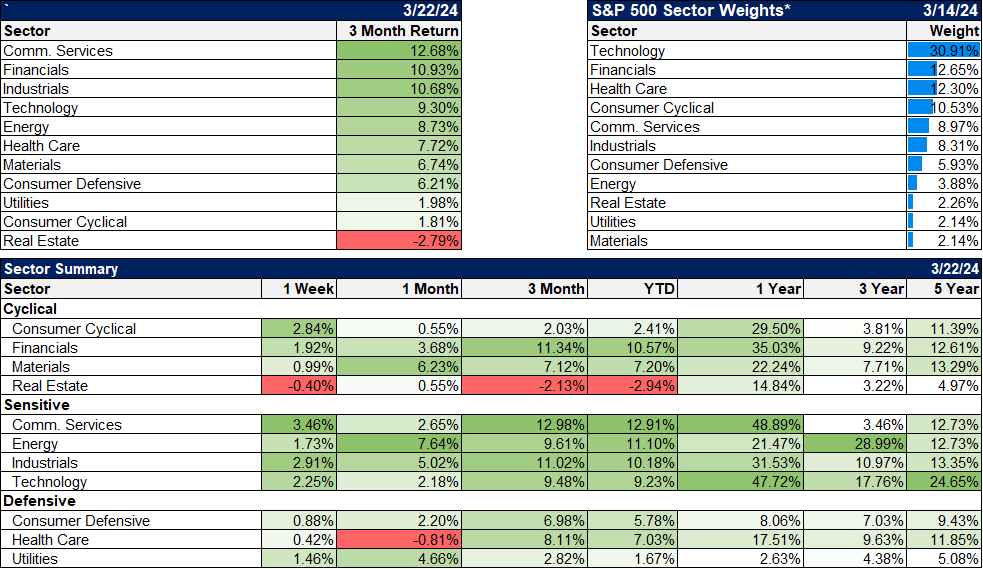

Sectors

The rally last week was broad based with 10 of 11 economic sectors higher. Real estate was the lone loser, down just 0.4%. Real estate is also the lone sector down YTD; it is still widely hated despite being up over 14% in the last year. Real estate isn’t going to lead until rates get in a more pronounced downtrend but that doesn’t mean it can’t provide good returns. Even in years when rates rise, REITs do pretty well.

Economic/Market Indicators

The economic data last week was all better than expected:

- Housing market index at 51 vs expectations of 48. This sentiment index is back in expansion for the first time since last July

- Housing starts 1.52 million vs 1.425 million expectations

- Building permits 1.52 million vs 1.495 million expected

- Jobless claims 210k vs 215k expected

- Philly Fed 3.2 vs -2.3 expected. Also a big rise in Business Conditions (38.6 vs 7.2 last month), CAPEX (23.6 vs 12.7), new orders (5.4 vs -5.2) and prices paid (3.7 vs 16.6)

- Existing home sales 4.4 million vs 3.9 million expected

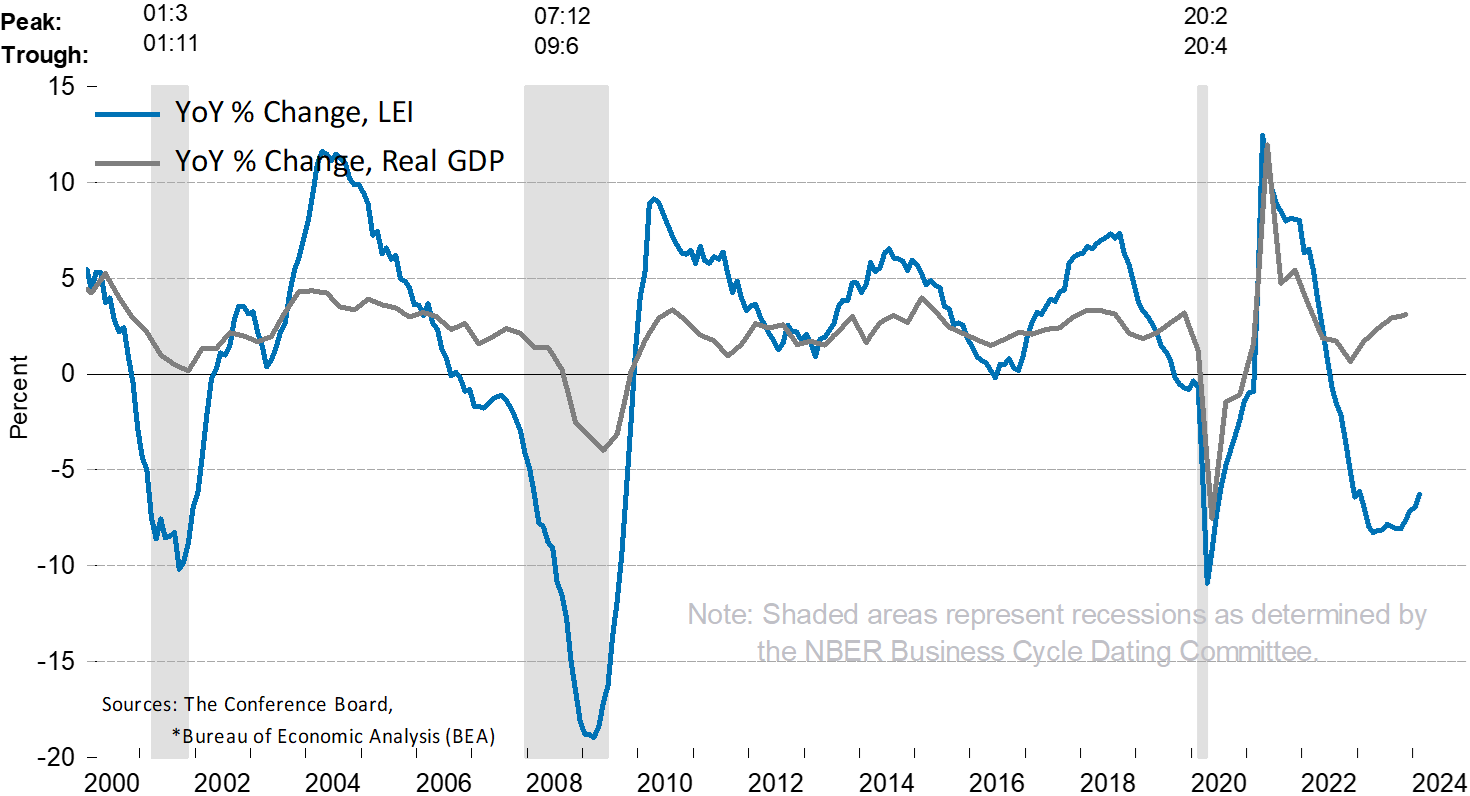

- Leading economic indicators +0.1% vs -0.2% expected and the first positive reading since February 2022. It looks like the goods production side of the economy is recovering.

Credit spreads fell again, to within 2 basis points of the low for this cycle set in late 2021. Prior to that one has to go back to the summer of 2007 to find a lower reading and that is somewhat discomfiting as that was not a time to be complacent. However, we have seen lower readings in the past so the spread can get tighter still. All we can really say is that there is no stress in credit right now.

You might remember last year the fear was that lower-rated companies were facing a “wall of maturity” with lots of low rated debt and loans coming due over the next few years. Well, narrowing spreads has allowed a lot of companies to refinance already and the pick up in debt cost has been fairly modest at less than 200 basis points (that was nearly 500 basis points as recently as 2022). The wall of maturity isn’t looking nearly so tall now.

Stay In Touch