It wasn’t actually Keynes who coined the term “pump priming”, though he became famous largely for advocating for it. Instead, it was Herbert Hoover, of all people, who began using it to describe (or try to) his Reconstruction Finance Corporation. Hardly the do-nothing Roosevelt accused Hoover of being, as President, FDR’s predecessor was the most aggressive in American history to that point, economically speaking.

Roosevelt just took it a step (or seven) further.

The principle is of pump priming is simple enough, and it was Keynes who gave the idea its intellectual framework. During depression, or even mere recession, depressed “aggregate demand” can be shifted higher by an influx of government spending. All the better if it is financed by more debt. Anything to get the economic cylinders firing again, for it was believed that without anyone priming the pump the downturn would just go on and on.

In the early thirties, it certainly did seem that way. The Great Contraction spanned several years, leading many Americans and others around the world to question if it would end. How anything could end it. Giving FDR the benefit of the doubt, repeatedly, wasn’t outlandish.

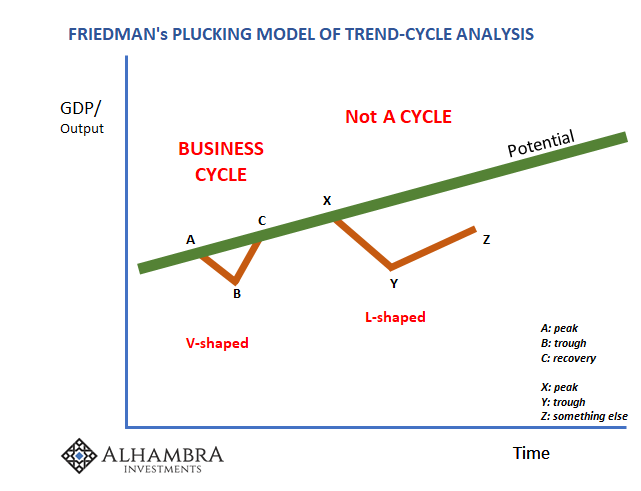

But that has proved the exception. In the post-Depression era, recessions were relatively quick affairs, taking on the noticeable “V” shape. A downturn, however painful, followed immediately by a robust upswing that for both parts led whatever economy back to where it began (untarnished potential).

What we’ve been witnessing since 2007, only starting with the onset of the Great “Recession”, is something else. The downswings can be, and often are, prolonged. The rebound parts are, too, if only because they are so unusually shallow. The entire process, down and up, seems to have been elongated.

By what?

Many Keynesians, like Paul Krugman, used to regularly decry government spending. There was never enough. At any lack of significant acceleration in budgetary outlays they would altogether cry AUSTERITY!!!! and write about the heartlessness of every fiscally-minded politician who didn’t prime the pump as much as they liked.

The question remains, what can it be that holds down economic conditions for so long, and then persistently retards the way back toward the healthy condition?

To me, the answer is clear enough – as I wrote yesterday. The evidence for it is substantial, consistent, and explains all the facts. Today, even more for the elongation starting in the same spot. Germany.

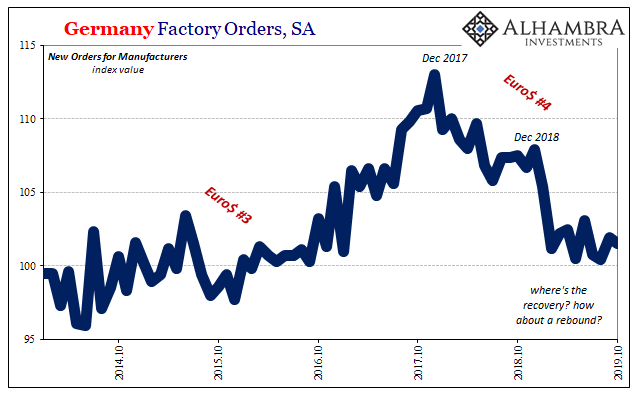

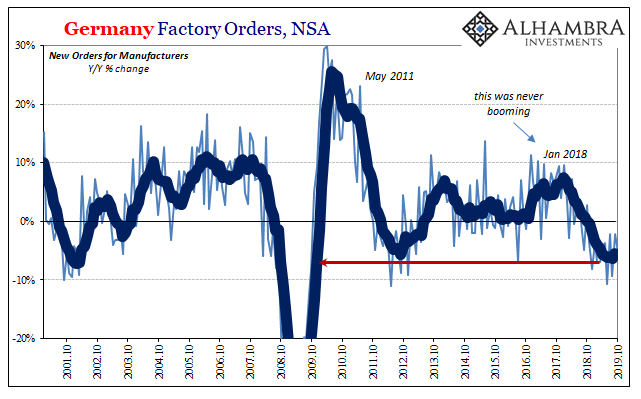

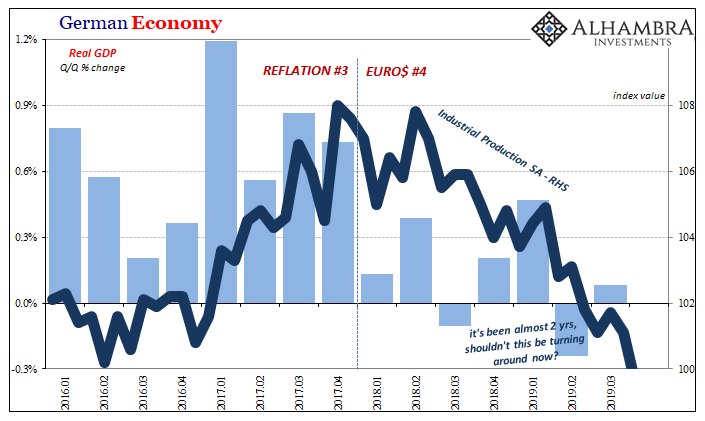

On Thursday, deStatis, Germany’s government agency responsible for keeping track of its economic accounts, reported that Factory Orders in its manufacturing sector remained, to put it kindly, subdued. As you can see above, with data now including October 2019 it makes an astounding 22 months stuck in this shape.

Since early this year, orders for new goods haven’t grown worse, but somehow they haven’t gotten better, either. On an unadjusted basis, factory orders are still contracting at an alarmingly steady 6% annual rate.

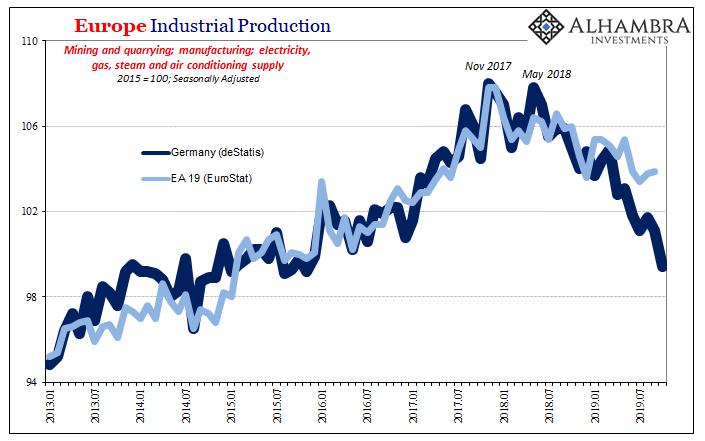

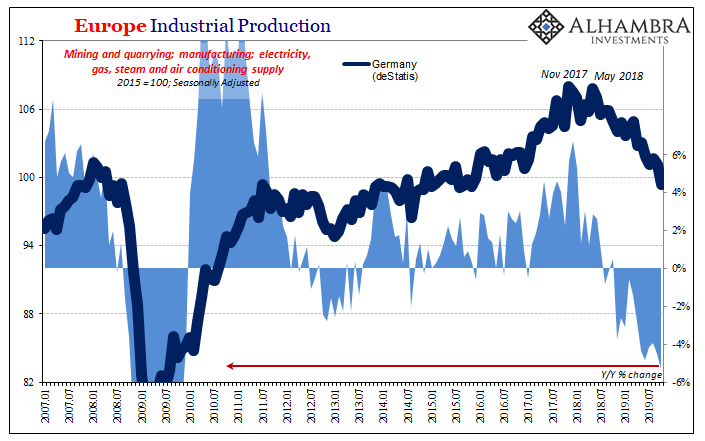

And that’s actually the good news, the best case for Germany’s economy. In terms of production, meaning Industrial Production, the near two-year slide in the sector continues to slide even faster.

Today, deStatis said that Industrial Production in Germany fell by more than 5% year-over-year in October. In the seasonally-adjusted series, above, it was that very ugly and alarming lurch to the downside; the latest one in what seems to be an unending string of them.

It has taken German industry almost two years of contraction to only now begin to look too much like 2009; surpassing the European recession of 2012 in every dimension, depth as well as length.

Yeah, something’s seriously wrong with this picture. Mario Draghi’s fantasy boom of 2017 is a distant and comparatively unsatisfying memory.

Again, we have to ask, how is this possible? It not only breaks with the pre-crisis convention for economic cycles it is actually a multi-layered breakdown. Each downturn in industry and therefore economy means a multi-year period without any possible upside growth, and then these are strung together one after another. They have left Europe, as the rest of the world, to fall further and further behind.

Production in Germany, the envy of Europe, as of October 2019 is 2% below what it was at the pre-crisis peak in January 2008.

Here’s the thing: for now eleven years going on twelve, authorities worldwide have responded just as the Keynesian textbook demanded. Entirely focused on this obvious shortfall in “aggregate demand”, central banks and, yes Dr. Krugman, even governments have been priming, priming, and priming themselves and us into oblivion.

The fact that it hasn’t worked – and it is a fact which authorities do admit if only on their own terms (R*) – has left them to only consider whether the world’s pump just won’t be primed. They’ve come to the conclusion the economic pump itself must be broken.

But instead of focusing every energy and attention on making up for any shortfall in aggregate demand, why not pay some to actually figuring out why it is and so stubbornly remains short in the first place? Rather than only considering getting the economy back up, maybe start to contemplate why it only falls down?

These are, sadly, rhetorical questions. The answer authorities won’t give is that they really don’t know what they are doing. There are times, even to the tune of multi-year periods, where it really shows up. Forget priming and pumps, just figure that much out (and stop it with the “trade wars” nonsense).

This isn’t just a problem for Germany and Europe. Despite today’s awesome payroll numbers in the US, these results from across the Atlantic are more applicable to our own upcoming circumstances than those. Globally synchronized downturn two years in the making and only now just getting more in sync.

Stay In Touch