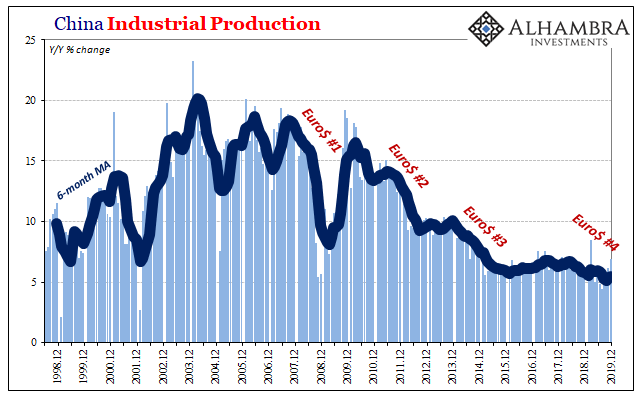

Chinese Industrial Production accelerated further in December 2019, rising 6.9% year-over-year according to today’s estimates from China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). That was a full percentage point above consensus. IP had bottomed out right in August at a record low 4.4%, and then, just as this wave of renewed optimism swept the world, it has rebounded alongside it.

Rather than suggest the global economy is picking up, or ended last year in a “good place”, when placed in context of the rest of China’s economic numbers we are left with the impression of an isolated instance. Perhaps a sugar high as any number of firms rushed to overproduce in order to get product in and out ahead of the expected imposition of new tariffs and restrictions.

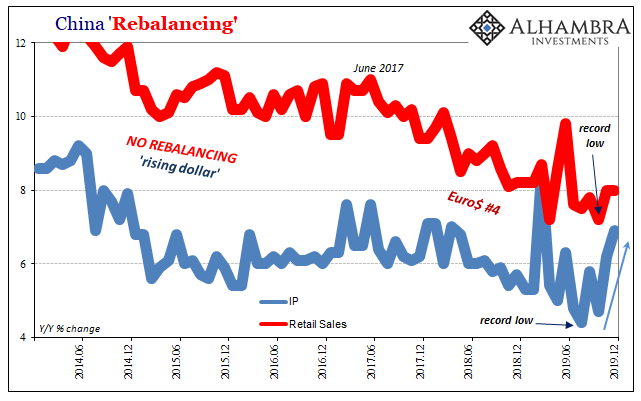

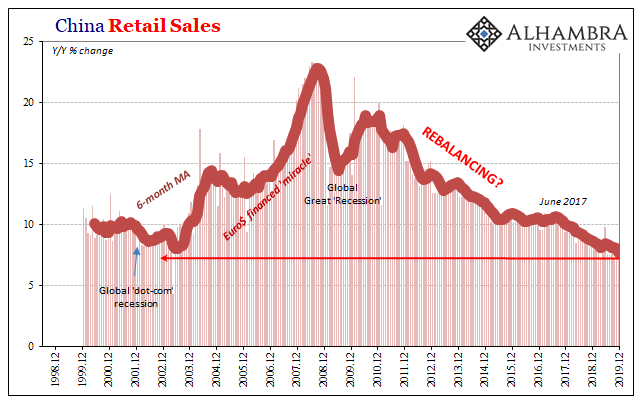

While IP has been higher, conspicuously so, Chinese retail sales have not. Up from a record low of 7.2% in October, but unlike IP not by that much. The NBS estimates that retail sales increased by 8% year-over-year for the second straight month in December.

As a result of this continuing string of historic weakness, the 6-month average is now the lowest on record.

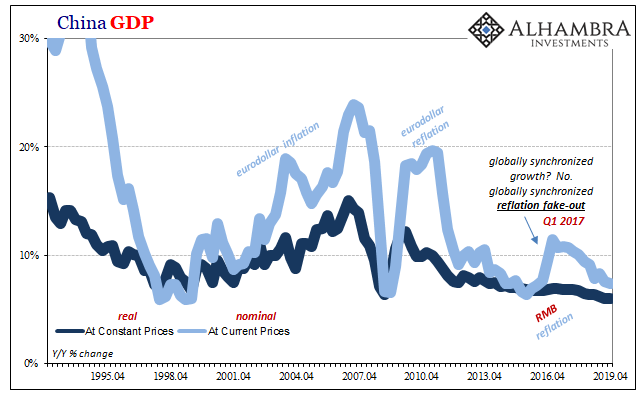

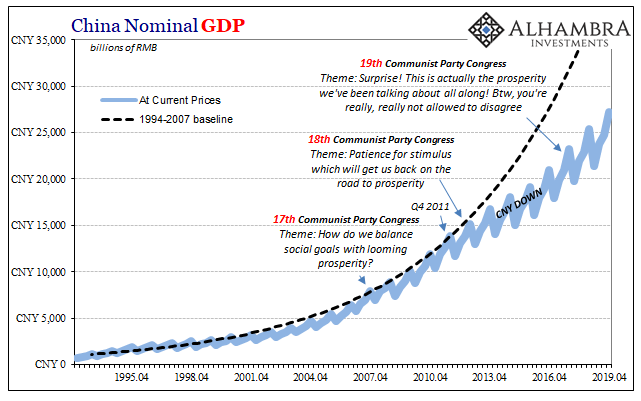

Because of that bump in IP as well as a similar (and questionable) acceleration in Private FAI, real GDP in the fourth quarter stabilized. But “stabilize” actually means contraction in terms of China’s economy, and therefore it won’t stay stable for long. The system requires some meaningful stability, which means rapid acceleration and therefore something more than narrative.

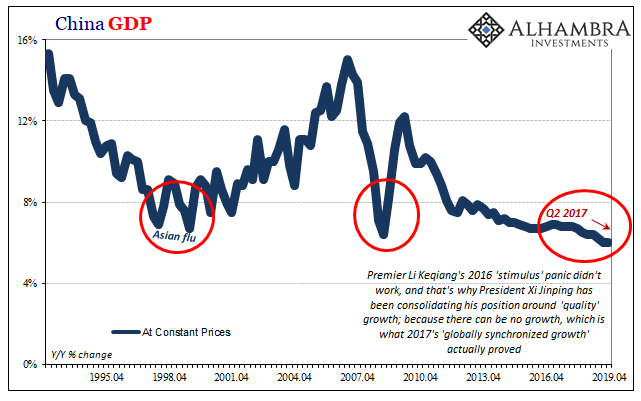

Following a 6.0% year-over-year increase in Q3, in Q4 it was another quarter matching a modern low.

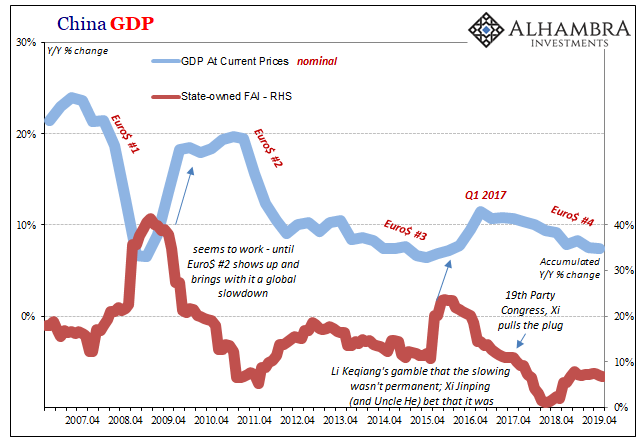

In more important nominal terms, Chinese GDP decelerated again. From just above 10% in Q2 2018, once CNY fell so has nominal output. There had been a minor rebound in Q2 2019, where the growth rate accelerated modestly (while commentary at the time was anything but modest about it) to 8.3% from 7.8% in Q1, but over the last half of last year the second half rebound never showed up.

Instead, nominal GDP decelerated first to 7.6% in Q3 and now 7.4% in Q4 2019.

The whole of China’s economy finished last year in the opposite direction of industry, thus suggesting what had been driving manufacturing output was doing so in that one sector alone.

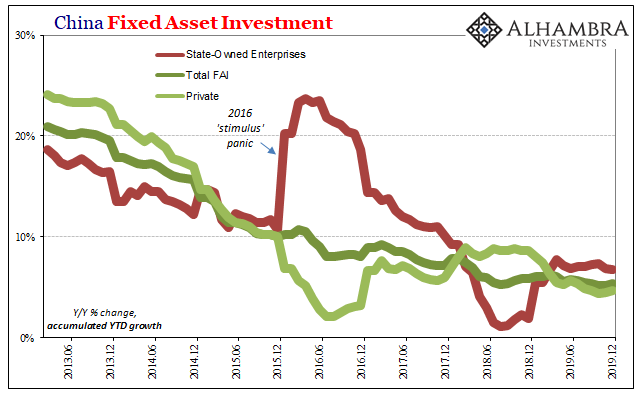

The Chinese economy is not crashing, either, a condition that the Communist government seems intent on maintaining. Managed decline. From the latest estimates for Fixed Asset Investment (FAI), we see that no matter how much total output slows authorities continue to shun the Keynesian textbook approach.

Rather than a “flood” of fiscal “stimulus”, which shows up in these accounts in FAI for State-owned Entities (SOE), it’s more of a fine-tuning.

The government created some modest additional activity through this channel at the start of 2019, a historically modest program, and then largely maintained that level throughout the year regardless of the economic performance in between; including, obviously, the general and ongoing slowdown in the second half.

There isn’t any indication, certainly not in the current estimates, nor in recent pronouncements, that anything substantial will change going forward. The government has already indicated it will allow real GDP to decelerate further this year. Having set a target range of 6.0% to 6.5% for 2019, and coming in at the lower end, authorities indicated they’re comfortable with a softer target “around 6%” in 2020.

That is consistent with managed decline and therefore inconsistent with a rapid rebound in China’s vast industrial sector; at least one that will continue for reasons other than pulling forward production.

That makes two data points, both Chinese, which might line up with improving sentiment and therefore the hope that the global economy could be turning around. At least they would line up if they were corroborated by the rest of China’s economy which, most people should realize, if there is any chance for a turnaround it is this one that must be at the center of the rebound for it to have any realistic shot.

It’s just not indicated here. Instead, the downturn grinds forward into a third year with instead minor and, dare I write, only “transitory” factors to the upside. In other words, 2020 begins with more global headwinds and disinflationary pressures.

Despite “trade deals”, record high stock prices, and general positivity breaking out seemingly everywhere (at least when compared to August when China IP and bond yields were together breaking records on the lower end), there must be some reason why the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield hasn’t budged.

Ongoing problems in Europe, emerging ones in the US labor market, and a Chinese economy that keeps letting everyone down – if only because the narrative-makers continue to read from Keynes.

Stay In Touch