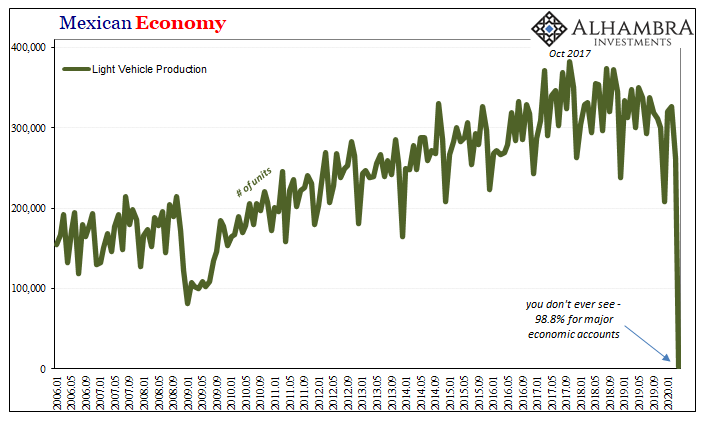

Compared to every other manufacturer, Kia’s production facilities in Mexico were positively booming. According to that country’s Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI), last month the Korean carmaker produced 1,907 of its Forte model. Yet, that small amount accounted for more than half of all light vehicles assembled during the month of April 2020.

For the whole country.

When statistical agencies put out numbers like these, they are done via surveys and turned into statistics via models because the amounts involved are beyond human capabilities. Last month, though, INEGI could’ve counted all the cars produced in Mexico by hand. That’s how few rolled off the lines.

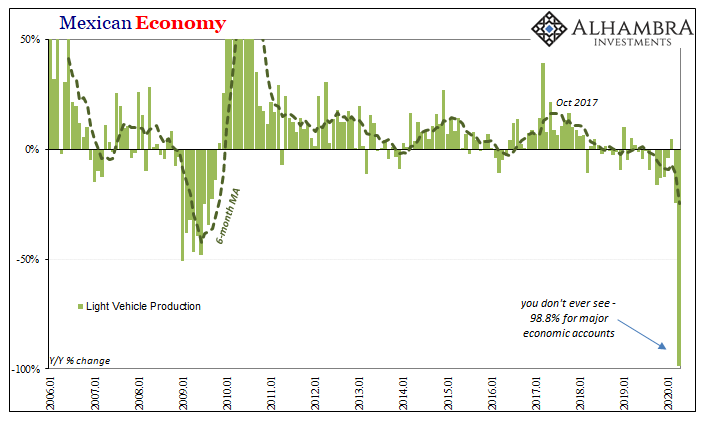

You never expect to see a -98.8% year-over-year change, at least not for any major economic figure for a serious national industry. But that’s what just happened south of the border for a key economic component – not just of and for the Mexican economy, but as a proxy for the rest of us, too.

INEGI says just 3,722 light vehicle units were made across the whole of Mexico during all of April. Kia was practically the only company doing anything, and it wasn’t all that much; most of the rest of them reported all zeroes across-the-board.

By comparison, in April 2019 the number produced was 300,100.

Analysts, economists, observers, whomever they get to produce predictions for these things were thinking April’s decline would “only” get as far as -30% or so. The total shutdown, therefore, another unwelcome surprise – courtesy of what has to be severe demand destruction.

Many manufacturers had already completely closed down production by the time the government had declared a health emergency on March 30 (though “non-essential” activities were prohibited, it wasn’t clear if supply chain and complete manufacturing fell into that category since authorities left provisions dealing with crucial industries like autos vague, even after the April 6 issuance of further “technical guidelines”). The reason was the perception that demand isn’t going to eat through bulging global inventories anytime soon. Dealers in the US and elsewhere have got a ton of stock that’s going to need to be whittled down first, as quickly as possible.

It’s the most extreme two-step piece of the inventory cycle – falling demand simultaneously raises inventory which impacts production. When that happens, second order effects in this case all throughout the Mexican labor force as not even Kia is going to be paying all its workers at the same rate.

Layoffs to be brutal and widespread. Even if the stoppage is temporary, how are workers supposed to get through one, two, three? months of this (even if next month production rebounds to “only” -50% or something). Some companies, like Volkswagen, are paying their workers while the COVID-19 emergency lingers onward. Even so, unless things pick up quickly worldwide changes will have to be made.

These second order effects quickly become third order effects; spending suffers as does business investment.

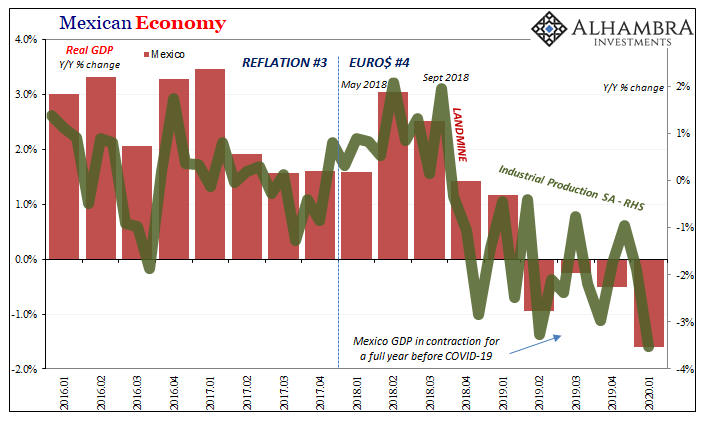

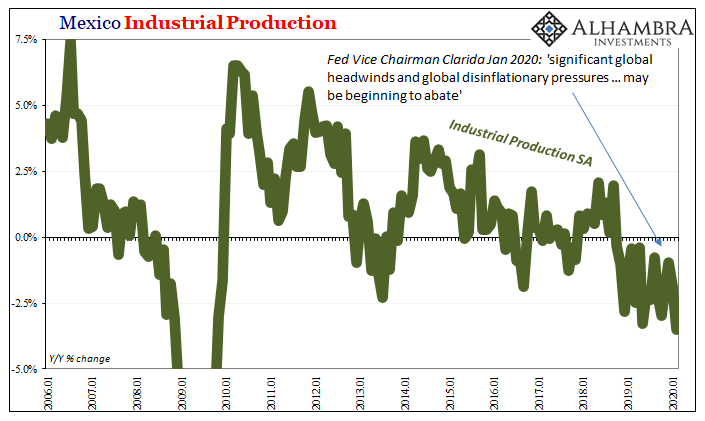

What’s happening here to the Mexican auto industry is an extreme example, to be sure. But it’s on the same spectrum as what’s going on elsewhere. After all, there’s a reason why automakers have become so pessimistic and cynical. It’s not like the auto business had been booming, suffering already more than two years under a downturn which had become a recession.

Fragility, in other words.

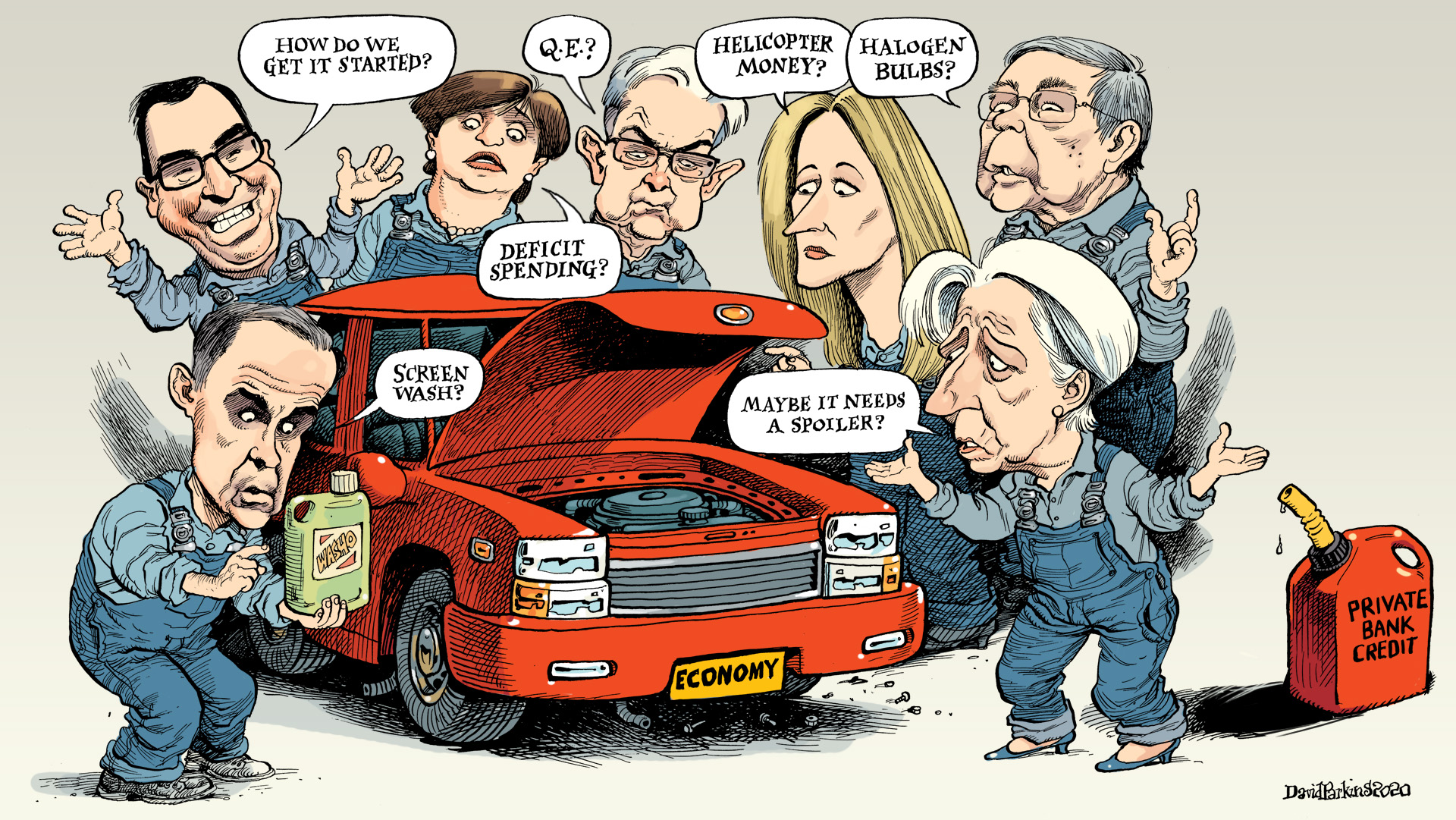

The whole point of monetary policies and “stimulus” in these situations is that second and third order effects don’t manifest, or can be kept to an absolute minimum. What that actually means is economic components from carmakers to auto workers to just consumers and businesses of all kinds who begin looking at the world differently because of what has happened.

Differently as in a bad sort of differently.

Shocked by the present and therefore thinking the future will be different than it was in the recent past, behaviors get changed. When you see numbers like these, even as extremes, it is exceedingly difficult to see how all across the global economy it’s not being re-evaluated exactly in that way. Things will be different. They have to be.

You don’t go into complete shutdown and then come out the other side like nothing happened. And then, disgustingly, to be told to depend upon “stimulus” as the crucial element clinching the argument for how everything will end up returning to normal? What normal?

I never thought I’d see a -98.8%. But there’s a better chance of seeing it again than there is for “stimulus” working big inflationary miracles.

Stay In Touch