No one could have possibly been surprised by the Fed’s lack of action on Wednesday. They had signaled to anyone who would listen that they would pause (skip, take a hiatus, halt, or whatever you want to call it) at this meeting. And no one should have been surprised that Jerome Powell offered some tough talk about the future of monetary policy at the press conference.

The stock market has been running hot lately with the most speculative things running the fastest and farthest. The Fed may claim to ignore the stock market but if there’s an easier way to check on whether monetary policy is easy or tight – at least in the US – I’m not aware of it. If folks are throwing money at stocks trading at 200 times sales then you can rest assured that there isn’t a lack of money out there. And that is, after all, what restrictive monetary policy is all about, isn’t it? If inflation is too much money chasing too few goods, the Fed only has a shot at changing one of those. And frankly, based on the evidence, they don’t have much control over that one.

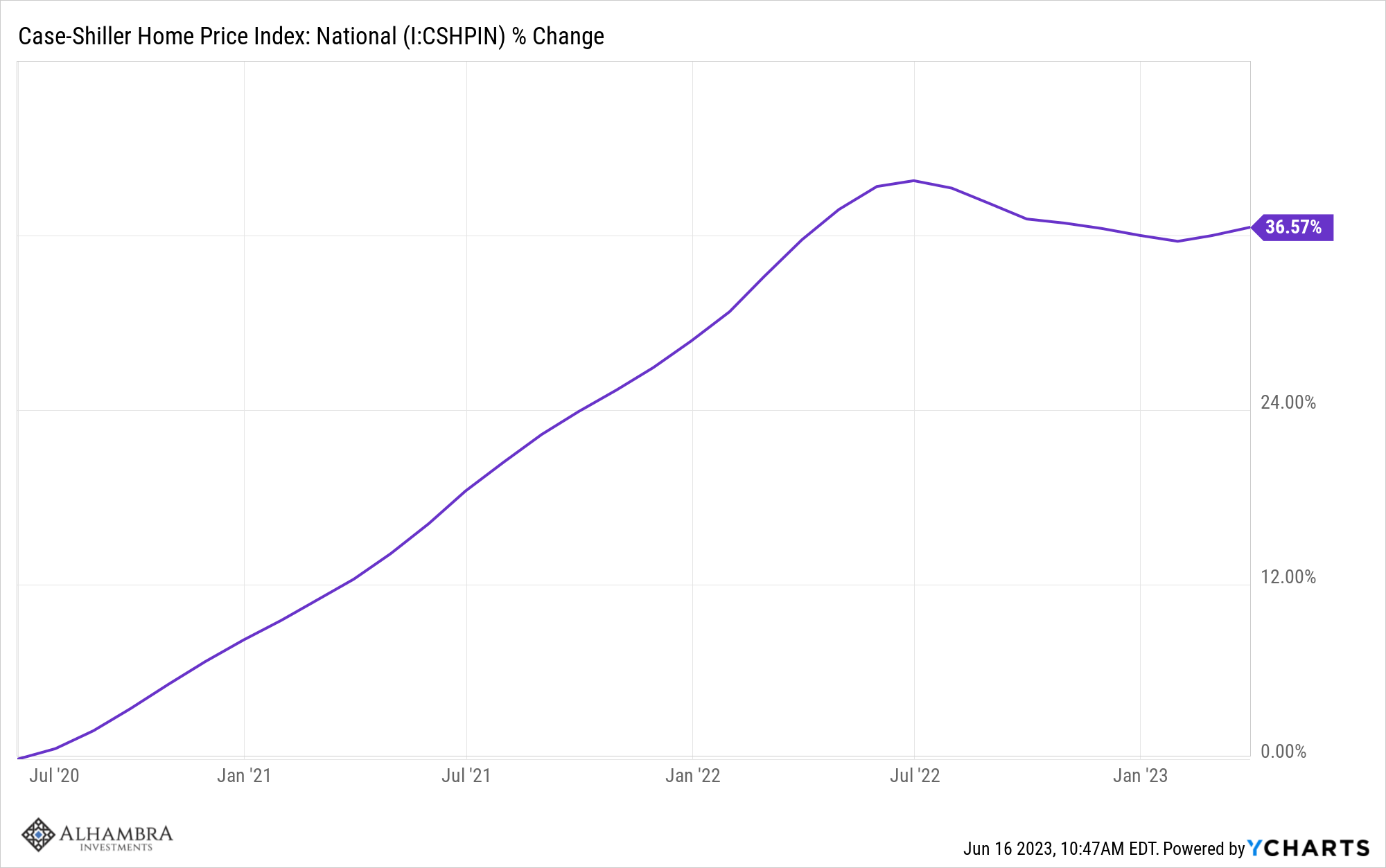

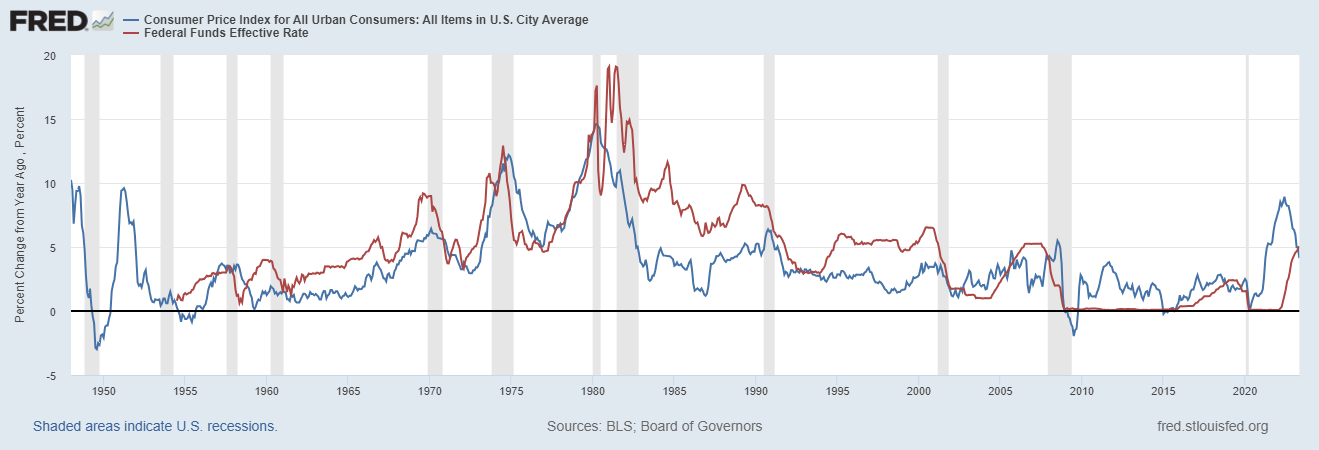

The official inflation figures have indeed moderated over the last year. Yes, it has been a full year since the year-over-year inflation rate peaked and the Fed has been hiking rates like crazy in that time. But correlation is not causation and finding evidence of the efficacy of rate hikes on the inflation rate is difficult. As far as I can tell, the only part of the economy the Fed has been able to impact directly is the housing market and even there, evidence of price moderation is iffy at best. Yes, the volume of sales has fallen – although that trend may be over – but house prices appear to have bottomed already.

The Case Shiller national home price index fell from 305.16 in June of 2022 to 296.06 in January of this year, a total drop of just 2.98%. Prices rose in February and March, despite high (relative to recent history) mortgage rates and the failure of several medium-sized banks. There is no evidence that I’m aware of that prices resumed their decline in April or May or this month. Why? The share of houses being bought for cash is the highest it’s been in over a decade. 36% of sales in 2022 were all cash, the highest since 2013 when investors were buying big. Institutional sales were only 6.5% of sales last year so this isn’t being driven by Blackstone and the private equity bad guys. In Augusta, GA, just 20 miles from my home in SC, 72% of sales last year were for cash. Higher mortgage rates are certainly having an impact but probably not in the way the Fed hoped.

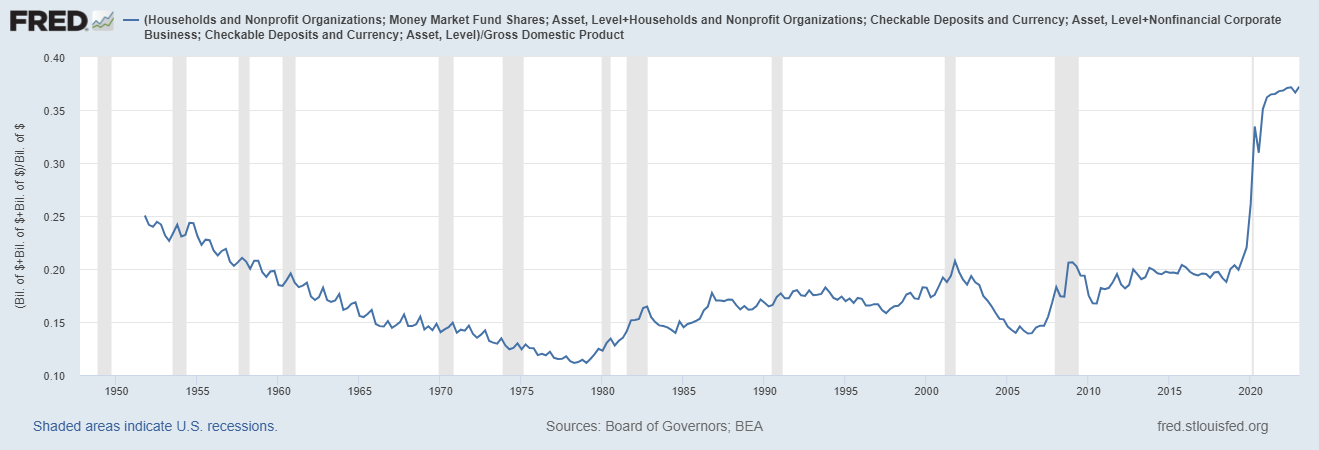

Why might that be? In a word, money. Cash. Moolah. Bread. Bucks. Benjamins. The chart below shows (household and non-profits checkable deposits and currency + household and non-profits money market shares + nonfinancial corporate business checkable deposits and currency) as a percent of GDP.

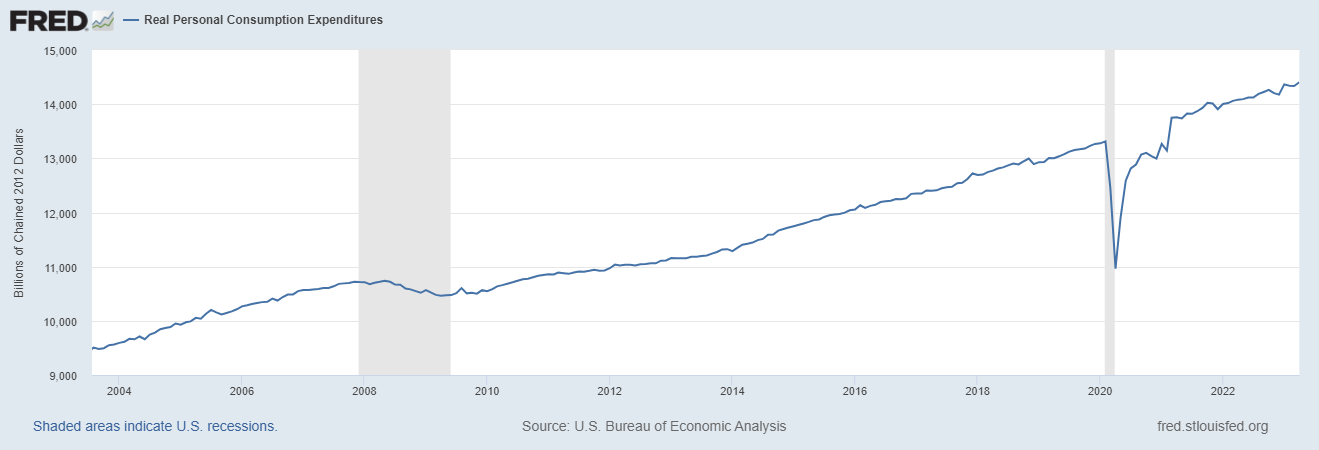

That’s 37.2% of GDP sitting around in cash or near cash. Meanwhile, household debt as a percentage of GDP has been falling since 2009 except for a brief blip higher at the beginning of COVID. It is hard to affect the economy with higher interest rates if consumption and investment aren’t reliant on new debt. That’s also probably why the yield curve hasn’t been the reliable recession indicator it has been in the past (at least so far). Yes, the official inflation rate has been falling but I don’t think it has much or anything to do with the Fed, at least not yet. Prices are rising at a slower rate because the supply of goods and services is catching up – or has caught up in some sectors – with demand that continues to rise on trend.

Here’s another indication that people have money to burn. The sports gambling handle (the amount of money bet) was a little over $13 billion in 2019. In 2020, during the heart of COVID, that total jumped to $21.5 billion and it has only climbed from there. 2021 totaled $57.7 billion, 2022 $93.8 billion and gamblers have already bet $40.4 billion through May of this year. That is truly disposable income and Americans have a lot of it. I realize, by the way, that more states have legalized sports gambling in that time so some of that is just shifted from illegal gambling. But that isn’t all of the gain.

Total gambling revenue hit an all-time high in 2022 of over $54 billion (revenue represents the win rate and typically runs about 7% of the handle). Still not convinced? How about virtual sports gambling? Ponies aren’t running? No problem. The point is that if gambling revenue is hitting all-time records and climbing double digits every year, there isn’t a lack of money. By the way, you may have noticed that I’ve written critically of gambling repeatedly over the years. I’m no prude but I abhor gambling for all the corrosive effects it has on our society and I am appalled that governments not only allow but participate (through lotteries) and encourage it. It is ruining sports and you can’t convince me otherwise. But I digress….

What is more interesting than the level of cash in the economy is the fact that it isn’t falling. I’ve read article after article over the last year about how the “excess” (who decides what’s excess?) savings from COVID has been or will soon be spent. It just isn’t happening. The Bank of America Institute’s Consumer Checkpoint (see here) reports that savings and checking account balances for all generations are still well above pre-COVID levels.

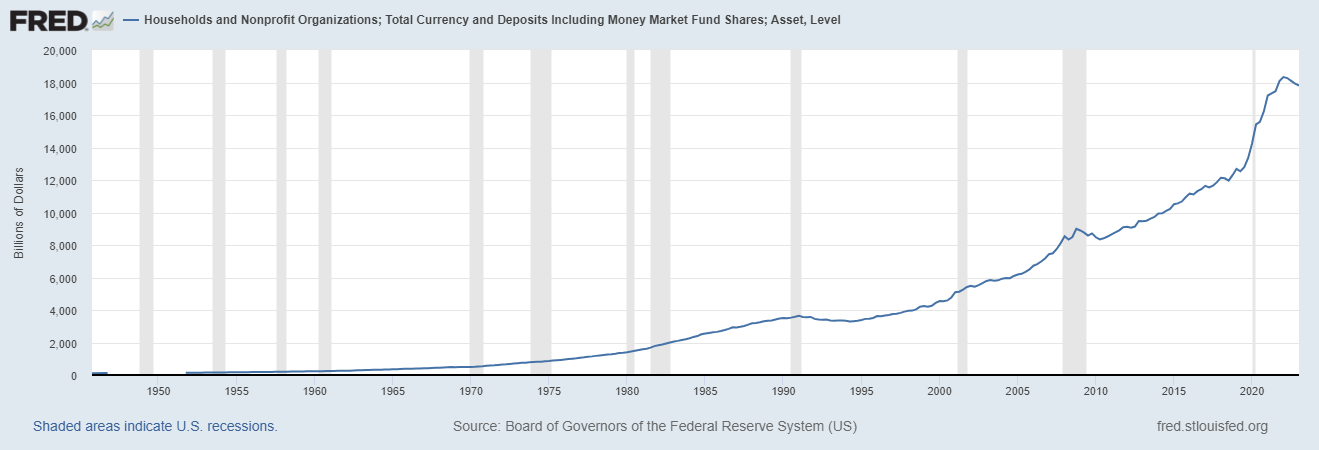

Total time and savings deposits have fallen by $1.2 trillion since the peak in Q1 2022 but is that really surprising? Have you seen the rates that banks pay on savings? Roughly half of the drop in savings balances has just shifted to money market funds, which are up $600 billion over the same time frame. If you want to find the rest of that savings – and more – look no further than the Treasury market, where households and non-profits have raised their holdings by $1.4 trillion since Q1 2022. There are a lot of moving parts to the household balance sheet and this isn’t intended to be a full accounting but just looking at total currency and deposits including money market shares, we see that the total is still $4.5 trillion higher than the end of 2019 and down only about $500 billion from the peak.

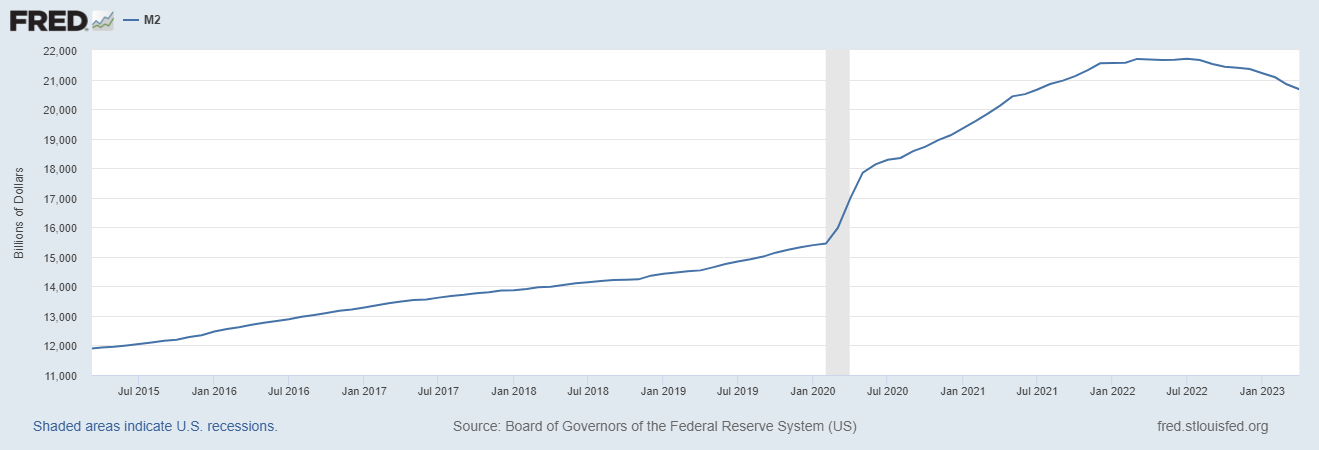

The Fed may be reducing money supply (M2 is down 4.6% year-over-year) but it rose by $5.2 trillion from February 2020 to the peak in July of last year and it has only come back down by about $1 trillion. And I wouldn’t expect the Fed to continue QT too much longer lest they push M2 below the pre-COVID trend. Or at least I hope not.

The point is that most of the vast amount of money created during COVID is still here and supporting economic activity. Money supply has fallen with QT so the Fed deserves credit for that and whatever impact it has had on the inflation rate, but the rate hikes are just theater and used to influence behavior, particularly that of investors. And based on the last few months of the NASDAQ, it isn’t working all that well.

The Fed indicated in their Summary of Economic Projections that they expect to hike rates two more times this year. The market is currently only giving them credit for one more hike with the probability of another 1/4 point hike in July at almost 75%. The highest probability for the rest of the year is for the Fed Funds rate to remain at 5.25-5.5%. As for me, well, I don’t try to predict things so much as react to reality but I’m not unaware of the possibilities. I have often over the last 18 months compared this time to the late 60s and early 70s and a peek back to that period may be instructive.

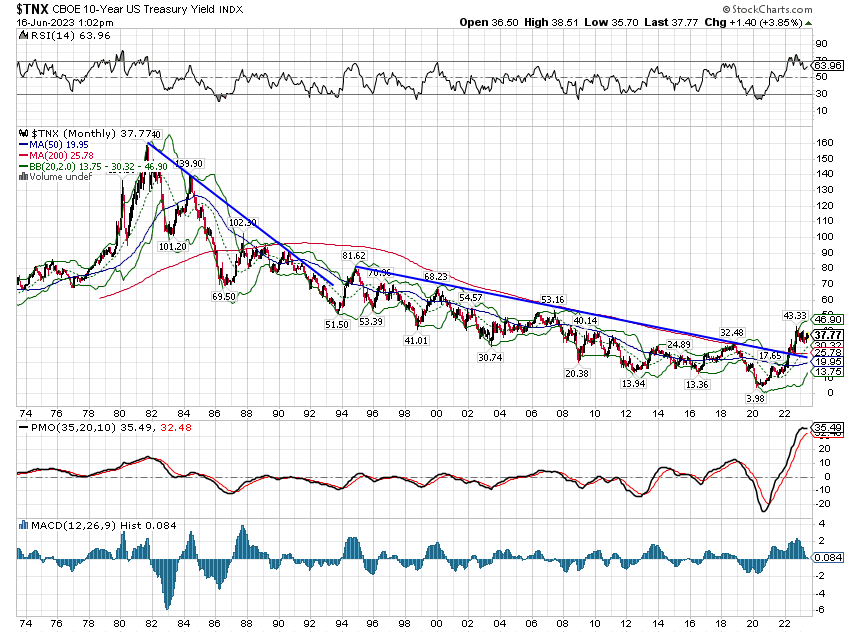

Right now, we’re a year past the peak in inflation. In the ’70 recession, it took inflation about 2 1/2 years to hit bottom and start rising again. In the ’73 recession, it took 2 years. That one was driven by the drop in the dollar and the oil embargo and it is easy to dismiss that as a possibility today. But given the geopolitical situation, I wouldn’t discount it too heavily. The final drop in inflation that started in 1980 took almost 3 years to bottom. Do we have another year or more of falling inflation to look forward to? And falling Fed Funds? Maybe. House prices peaked last June and fell for 7 months before hitting bottom in January. That drop should start hitting OER and core inflation over the next 7 months. If inflation drops rapidly over the next 7 months what does the Fed do? What does the dollar do? What do interest rates do? I think that’s what we need to be thinking about right now.

Having said that, while inflation may fall over the next year or so, I don’t think that will be the end of this inflationary period. I believe we are in the midst of a secular change in inflation and interest rates. While the parallels aren’t perfect, there’s a reason I keep comparing today to the late 60s. That was the first of what turned out to be three big surges in inflation over the next decade. I would argue – and have in the past – that the drop in inflation in the early 80s had as much to do with Reagan’s supply-side reforms – tax cuts and deregulation – as Volcker’s rate hikes. Or maybe a better way to say that is that Reagan’s supply-side reforms were why the inflation reduction was durable, unlike in the 70s. The positive outlook for the US economy drove capital flows to the US and raised the value of the dollar. And inflation is really about the value of money. That’s how we killed inflation for the next 4 decades.

And now, we seem to be repeating the mistakes of the 70s, relying on government industrial policy (IRA, CHIPs Act, etc.) to expand the supply side while continuing to expand the regulatory state (look at all the conditions placed on CHIPs Act money). That’s also why the rate hikes were so severe in the 70s. They had to go very high to kill demand and create a recession. But once inflation fell, the Fed would cut interest rates, nominal growth would resume and the inflation would come back because the supply side was still constrained.

It will take years for this to play out just as it did back then. The government spending that happens over the next couple of years will flow through to GDP because it is only about spending. But in the end, real growth is about productivity and I have no confidence at all that government-directed investment will efficiently raise productivity. I also don’t think it is a model that is likely to attract capital to our shores.

We will eventually have the recession everyone has been predicting for the last year. It might even come this year but I’m skeptical that it will be anything but a mild contraction. Why? It’s all about the Benjamins.

Stay In Touch