It’s the residual of all the stuff we can’t explain. It’s not that our models are wrong, it’s the dark matter that’s out there. – Fed Governor Neel Kashkari, referring to the “term premium” in long term Treasury yields

The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design. – F.A. Hayek, The Fatal Conceit

Economists are at this moment called upon to say how to extricate the free world from the serious threat of accelerating inflation which, it must be admitted, has been brought about by policies which the majority of economists recommended and even urged governments to pursue. – F.A. Hayek, The Pretense of Knowledge, Nobel Prize acceptance speech, December 1974

Term Premium and similar terms are the last refuge of central planning scoundrels everywhere. It is the fudge factor central bankers are using today to explain the recent rise in long-term interest rates. Term premium is defined as the extra yield investors require to hold long-term bonds instead of investing in a series of shorter maturities. It is the part of bond yields that rises and falls with uncertainty. That uncertainty might encompass a number of factors from the path of future Fed policy to inflation expectations to economic growth to credit risk.

Of course, we don’t really know and can’t know exactly why investors are buying or selling bonds at any given price. We can measure inflation expectations of course, but there are a variety of ways to do so, from comparing TIPS yields to nominal yields, to surveys of economists, to surveys of the public. The bigger problem is that inflation expectations are not correlated – at all – with actual future inflation. Do bond prices today factor in the uncertainty of the difference between current inflation expectations and actual future inflation? I have no clue and neither does Neel Kashkari.

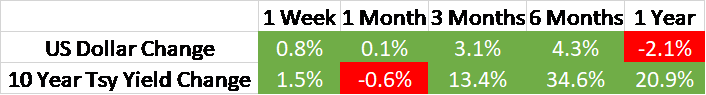

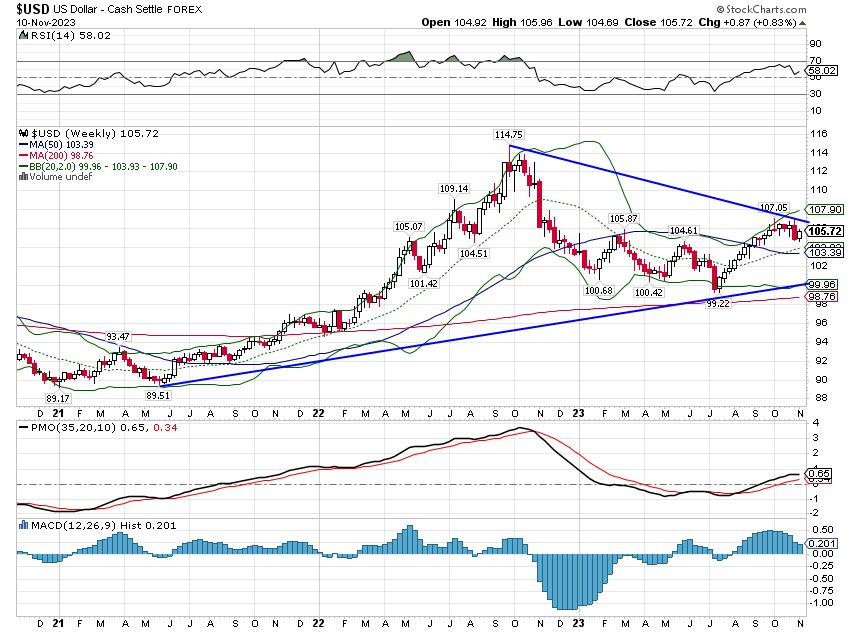

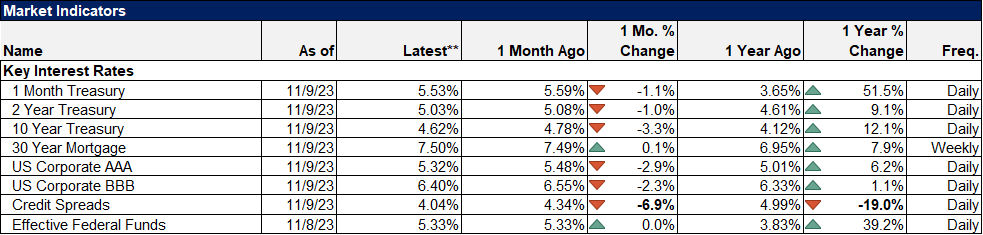

Bond prices fluctuated in a pretty wide range last week of about 18 basis points but the MOVE index – the bond market equivalent of the Volatility index for stocks – has been rising since bond yields started rising in August 2021. And it has been elevated to multi-year highs since the Fed started to hike rates in the spring of last year. So, if inflation expectations have fallen since then – and they have – then the rise in nominal rates has to be from either rising real growth expectations or uncertainty about the credit quality of the US or uncertainty around future Fed policy. The answer is probably some of all of those things but the question is impossible to answer.

There is, of course, considerable worry presently about the debt of the US government. Moody’s changed the credit outlook for the US to negative late Friday. We also had a poor 30-year bond auction last week where primary dealers had to buy more than usual of the bonds offered for sale. But we don’t know why the auction went poorly. It may have nothing to do with the creditworthiness of the US. It may be that the uncertainty around the other potential issues was the driving factor. Who wants to buy 30-year Treasuries with so much uncertainty about future growth and inflation? And don’t forget the Fed itself, which is producing Fed speeches at an alarming rate, nearly matching the rise in prices none of their previous speeches anticipated.

There are always those, like Mr. Kashkari, who think we should be able to model the economy and learn enough to guide the economy to our preferred – or at least his preferred – outcome. I am constantly amazed that economists who consider themselves staunch capitalists, believe that, given sufficient information, they could do what they firmly believe socialists and communists cannot. Namely, to shape the economy through policy, fiscal and/or monetary, to produce a better outcome than the market left to its own devices. In other words, they believe that central planning would work if only they were the ones doing the central planning.

Right now, both fiscal and monetary policy are attempting to guide the economy. The aim of those policies is sometimes at odds, as it is now with fiscal policy attempting to expand the economy while monetary policy seeks to restrain it. The result is that some of the fiscal policies are being offset directly by monetary policy. A new modular reactor project in Idaho was canceled last week, despite considerable government subsidies, because rising inflation and interest rates increased the cost of the project by 75%. Multiple offshore wind projects, part of President Biden’s green energy push, have been canceled recently for similar reasons. NextEra Energy saw its stock price drop by a quarter over 10 days in late September because of increased costs in its renewable energy unit, similar to the wind projects problems.

In addition to the intended and unintended consequences of economic policy, the economy is constantly changing on its own due to changes in consumer preferences, prices, scientific and technological discoveries, and any number of other factors. Throw in the changes induced by COVID and you get an economy that doesn’t act like everyone – anyone – seems to think it should, the Fed very much included. COVID, by the way, really only accelerated some trends that were already in place but the acceleration matters too. Here’s a video we did last week about changes in consumption since COVID.

Yes, there is indeed a lot of uncertainty about the economy right now and I guess that means that the term premium is rising. Uncertainty is always with us and I’m not sure it is worse today than, say, 10 years ago, but I do think that if the Fed wants to minimize it, they could do two things. First of all, they could just do less. It is the height of folly and hubris to believe that monetary policy can or should be used to fine-tune the economy. In attempting to exert a control they don’t have, the Fed itself disrupts the normal operation of the economy with little regard for the unintended consequences. And there are always unintended consequences. As evidence of the consequences of poor monetary policy, I offer this:

The second thing the Fed could do is even simpler: shut up. The constant talking, about the economy and what they think about future policy, makes the uncertainty around future Fed policy…well, uncertain. Interpreting Fedspeak can be a whiplash affair with one Governor hawkish and one dovish and some so confused they take to blaming “dark matter”. The whole idea behind more openness was to make future policy less opaque, for the Fed to provide “forward guidance” and thereby remove this uncertainty. But with so many voices speaking, so many egos jockeying for attention, they’ve accomplished the opposite.

The idea of forward guidance (what other kind of guidance would there be?) also makes the mistake outlined by Hayek in his Nobel acceptance speech – the pretense of knowledge. If the Fed was able to model the economy, if it was able to accurately predict economic variables, forward guidance would be great (or so we assume). But of course they can’t, so attempting it just adds to the uncertainty. Mr. Kashkari, your models are wrong and the evidence of that is staring you in the face. You call it term premium. I call it hubris.

Environment

With only minimal economic data to trade off last week, bonds meandered based mostly on whatever the Fed Speakers of the Day had to say. Well, there was the small matter of a 30-year auction that didn’t go very well, but that only moved the market a few basis points. The real market mover was a speech by the only Fed speaker that really matters, Jerome Powell. He apparently decided that what the economy needs right now is a little more interest rate volatility because uncertainty wasn’t already high enough. Or maybe he was just missing the spotlight and wanted to make sure everyone remembers he’s the boss.

Whatever the case, the trend for the 10-year Treasury rate remains up although off the highs of a few weeks ago. The economic calendar this week includes CPI, PPI, retail sales, three regional Fed surveys, industrial production, and housing starts so I expect to see a lot more rate volatility this week. Still, it seems unlikely that any of those reports will move the market enough to get a trend change.

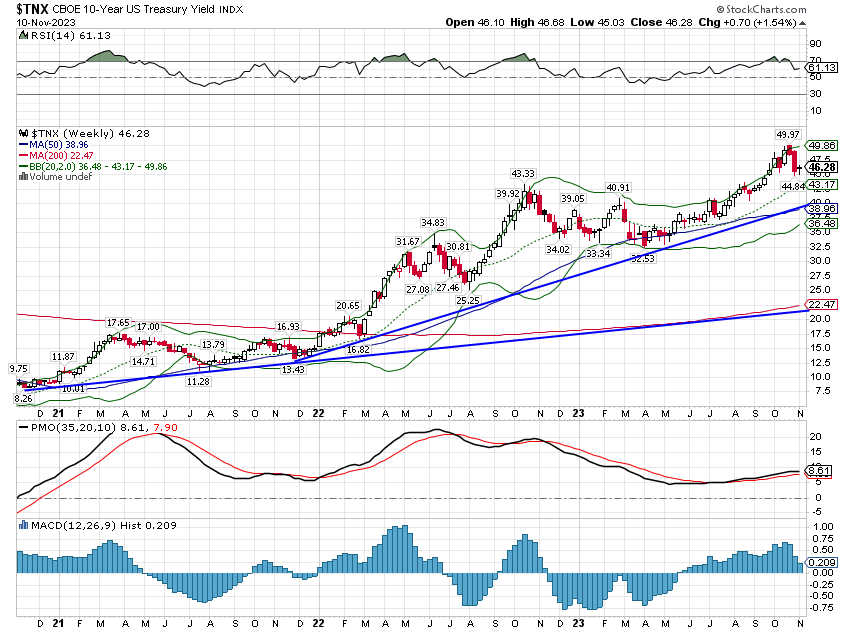

The dollar was a little higher last week but is still down over the last year. The buck has shown some weakness since peaking on October 3rd and that is likely a result of weaker growth expectations rather than inflation. Is the slowdown finally here? Economic data over the balance of this year is going to be very important.

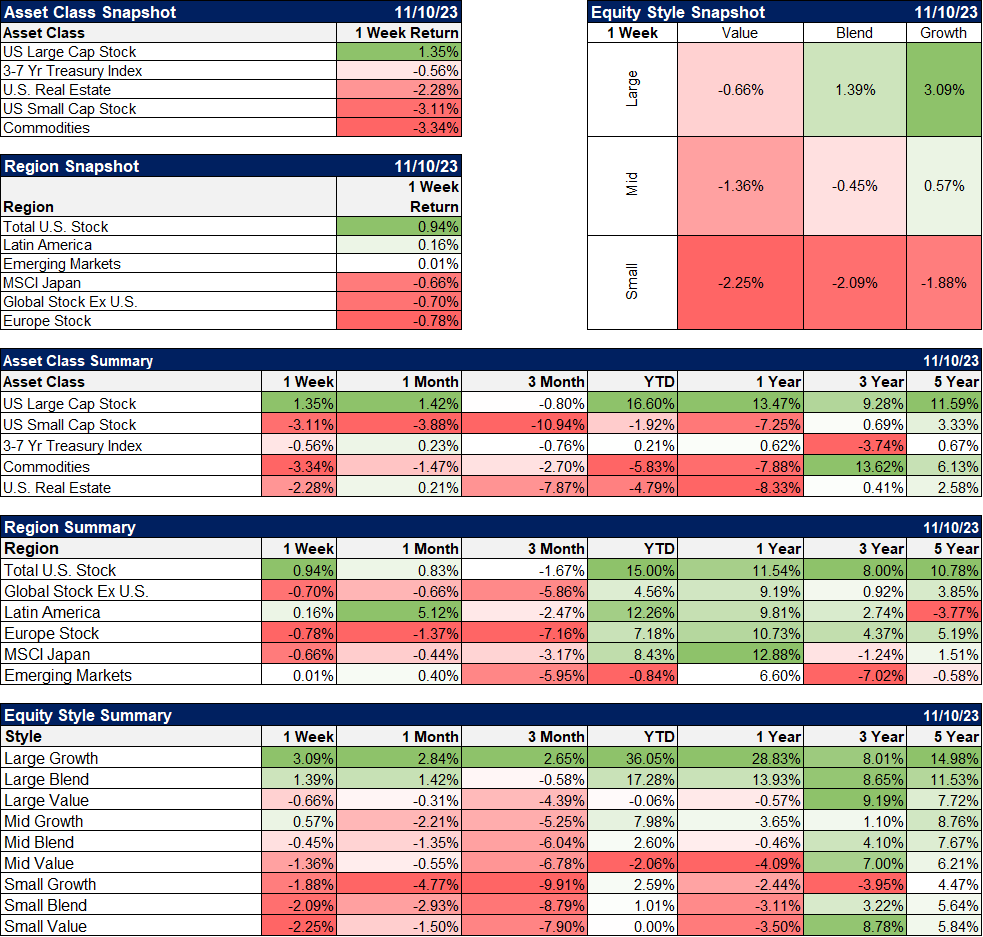

Markets

Large and mid-cap growth stocks managed to eke out gains for the week but that covers the positives. Commodities had a rough week mostly due to energy with crude down over 4% and nat gas down over 13%. Crude oil futures are flirting with contango again, which seems to be driven more by supply than demand. OPEC exports are up about a million barrels a day since August. We’re also seeing big swings in inventories as refinery shutdowns are up about 11% this year and early 2024 may be the heaviest maintenance season ever as companies catch up on maintenance deferred during COVID. In other words, the crude oil market is not where you want to look for clues about the economy.

Small-cap stocks had another tough week and the ratio of Russell 2000 to S&P 500 is back near its COVID lows. Earnings for small caps have been good this quarter with nearly 2/3 of companies reporting upside surprises. But small companies, much like their larger counterparts, are offering tepid guidance for Q4. From an earnings recovery perspective, small caps appear to be about a quarter or two behind large caps. But earnings look likely to be up quarter-to-quarter in Q3 so the earnings recession is probably nearing its end. One interesting tidbit is that real estate is providing the biggest contribution to growth, something we’ve also seen in large caps.

The only other positive for the week was Latin America and EM (which is really a function of LA). That was despite the fact that the Brazilian Real and the Chilean Peso both came off their recent highs. Both are still in short-term uptrends though as are EM currencies more generally.

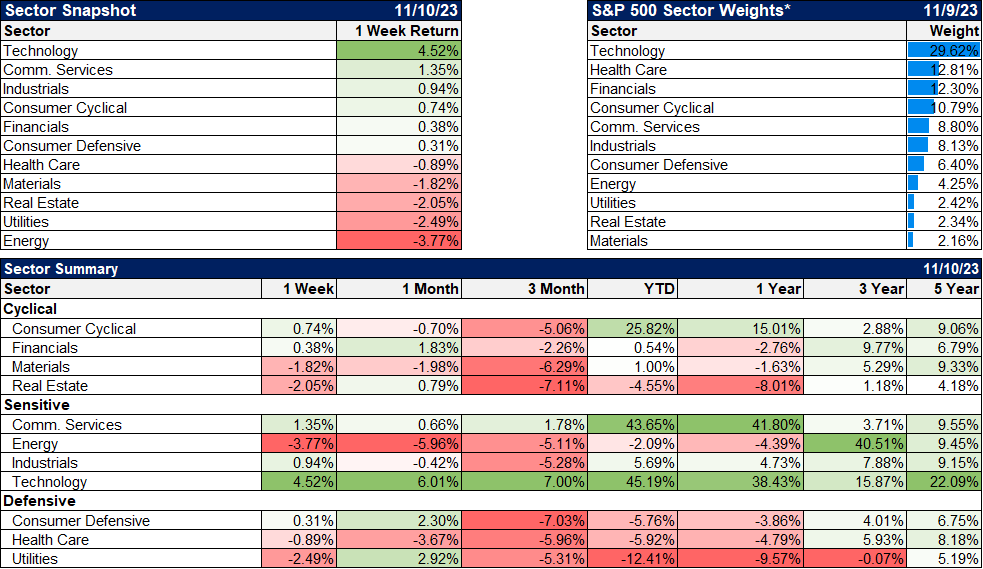

Despite the narrowness of the large-cap advance last week, the view from a sector standpoint was more even with 6 of the 11 sectors higher on the week. Technology and communication services led the way as they have all year while energy stocks fell with crude and nat gas prices.

Economics/Market Indicators

There weren’t a lot of reports last week but they were generally positive albeit in minor fashion. For instance, in the Senior Loan Officer Surveys, we see the percentage of banks tightening lending standards fell from around 50% to around 30% (that’s a blending of large and small firms). So it’s better but a third of banks are still tightening lending standards. For large firms, the percentage of banks reporting stronger demand for loans saw a similar improvement. Unfortunately, there wasn’t a similar improvement for small firms.

On trade, both exports and imports were up month-to-month. Exports were up for the third straight month and 5% since their June lows and very close to breaking to a new high. Imports are up 2 of the last 3 months and about 3.5% since June but are still well below the 2022 peak. So, again, positive but kind of mixed too.

The economy does appear to be slowing somewhat but the extent is not really known yet.

Credit spreads are back near their lows of the cycle. Spreads are wider in the junkier parts of the market but even in CCC spreads are 21% narrower today than at the peak in September of 2022.

The Fed employs 300 or so PhD economists and their estimates of future economic activity stand out mostly for their inaccuracy. The best predictor of the future economy is available to anyone who cares to pay attention – the markets. If interest rates are rising Mr. Kashkari, it is because expectations for future nominal GDP are rising. NGDP only has two variables – real growth and inflation – so it is easy to see which one is changing the most. Term premium is merely a way for you to avoid admitting you don’t know why those variables are changing.

Dealing with uncertainty is the hardest part of being an investor. You can reduce that anxiety by focusing more on those things that are observable in the real world and less on the ones that are theoretical or merely speculative. Spend your time focused more on the what rather than the why. It is easy to decipher what investors are anticipating but much harder to figure out why they are anticipating it. Leave the dark matter to the alchemists at the Federal Reserve.

Joe Calhoun

Stay In Touch