From The Burden of Bretton Woods, The Richard Nixon Foundation:

…by the 1960s, the expansion of global production and trade increased the amount of dollars circulated worldwide — so much so that dollar circulation far outstripped the U.S. gold supply. There simply was not enough gold to back excessive liquidity, making it evident that the U.S. dollar was overvalued.

Because the Bretton Woods system barred the United States from revaluing its currency, the Nixon administration pressured world leaders to revalue their currency. Their requests were heeded by some but ignored by others. Countries such as Japan were reluctant to do so lest they jeopardize their competitive export industry. As a result, countries began holding more and more U.S. dollars as reserve assets to maintain their value. By the mid 1960s, this practice was global; a third of the total market-economy reserves were held in reserve currency, a majority being made up of U.S. dollars.

From the “Nixon Shock” speech on August 15th, 1971:

The time has come for a new economic policy for the United States.

- The tax reductions I am recommending, together with this broad upturn of the economy which has taken place in the first half of this year, will move us strongly forward toward a goal this Nation has not reached since 1956, 15 years ago: prosperity with full employment in peacetime.

- Tax cuts to stimulate employment must be matched by spending cuts to restrain inflation. To check the rise in the cost of Government, I have ordered a postponement of pay raises and a 5 percent cut in Government personnel.

- I have ordered a 10 percent cut in foreign economic aid.

- 80 million American wage earners have been on a treadmill. For example, in the 4 war years between 1965 and 1969, your wage increases were completely eaten up by price increases. Your paychecks were higher, but you were no better off.

- I have directed Secretary Connally to suspend temporarily the convertibility of the American dollar except in amounts and conditions determined to be in the interest of monetary stability and in the best interests of the United States. Now, what is this action – which is very technical – what does it mean for you? Let me lay to rest the bugaboo of what is called devaluation. If you want to buy a foreign car or take a trip abroad, market conditions may cause your dollar to buy slightly less. But if you are among the overwhelming majority of Americans who buy American-made products in America, your dollar will be worth just as much tomorrow as it is today.

- As a temporary measure, I am today imposing an additional tax of 10 percent on goods imported into the United States.

- It is an action to make certain that American products will not be at a disadvantage because of unfair exchange rates.

- As a result of these actions, the product of American labor will be more competitive, and the unfair edge that some of our foreign competition has will be removed. This is a major reason why our trade balance has eroded over the past 15 years.

…now that other nations are economically strong, the time has come for them to bear their fair share of the burden of defending freedom around the world.

A client recently asked me why I am so concerned about the dollar. I told him that the conditions that existed in the early 1970s are quite similar to those of today and that the complaints and policies of the Trump administration eerily echo the grievances and policies of the Nixon administration.

- Nixon blamed the problems facing the US mostly on his predecessor for fighting a war in Vietnam and also overspending on domestic programs, the Great Society reforms of the Johnson administration. The deficits caused inflation to spike to 6% by 1970, early in the first Nixon administration.

- He blamed the US’s emerging trade deficit on:

- An overvalued dollar that resulted from other countries accumulating large dollar reserves.

- Unfair trade practices by other governments including tariffs and non-tariff barriers

- Nixon blamed the inflationary policies of his predecessor for causing real wages to stagnate

- Nixon believed other countries were not paying their fair share of “the burden of defending freedom around the world”.

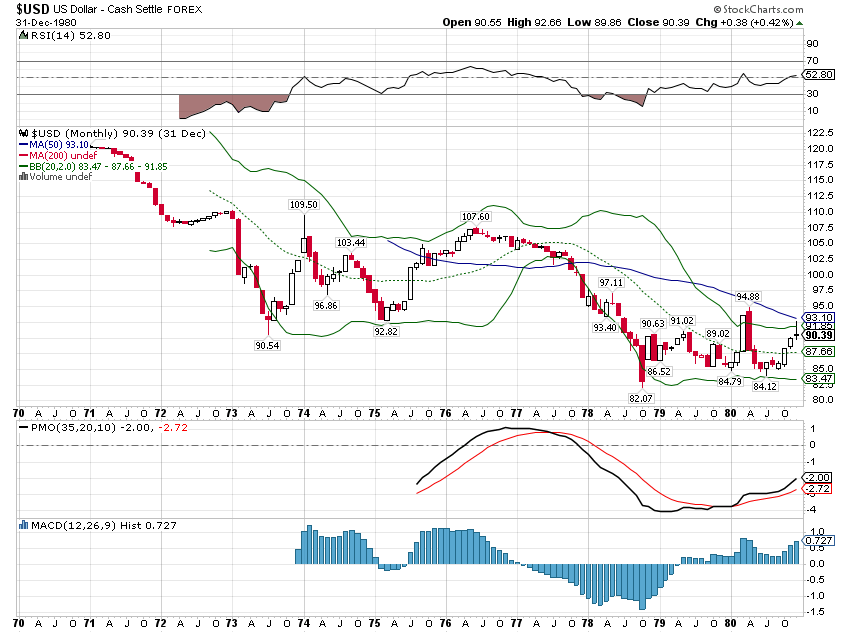

By the end of 1971, in what became known as the Smithsonian Agreement, the US convinced most of the other Bretton Woods countries to revalue their currencies higher against the dollar. The dollar peg was revalued from $35/ounce to $38/ounce of gold (8.5%). The dollar was still overvalued though and speculators forced the end of Bretton Woods by 1973 when the dollar and the other major currency values became market-determined (free floating). From the beginning of 1971 to July 1973, the dollar index fell 25% and eventually hit a low of 82.07, down 32%. (It closed the decade at around 90, still down 25% from its pre-shock level.) Nixon also imposed a 10% tariff on all imports and proposed tax cuts as stimulus for domestic investment.

Today, President Trump:

- Blames his predecessor for most of our economic problems. As an aside, Nixon and Trump were right about the inflationary policies of their predecessors but both also implemented inflationary policies of their own and both pressured the head of the Fed to ease monetary policy (Nixon successfully and Trump unsuccessful so far).

- Blames our trade deficit on:

- An overvalued dollar caused by other countries accumulating large dollar reserves (Stephen Miran, Council of Economic Advisors and Scott Bessent, Treasury Secretary)

- Unfair trade practices by other governments including tariffs and non-tariff barriers, including keeping their currencies undervalued versus the dollar

- Blames his predecessor(s) for policies that have caused a stagnation of working class wages

- Believes other countries are not carrying their fair share of the global defense burden (J.D. Vance, Miran, and Bessent)

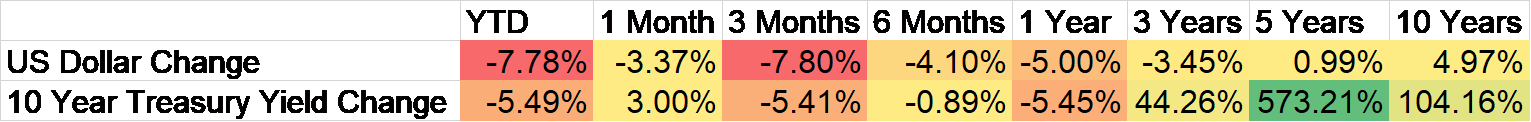

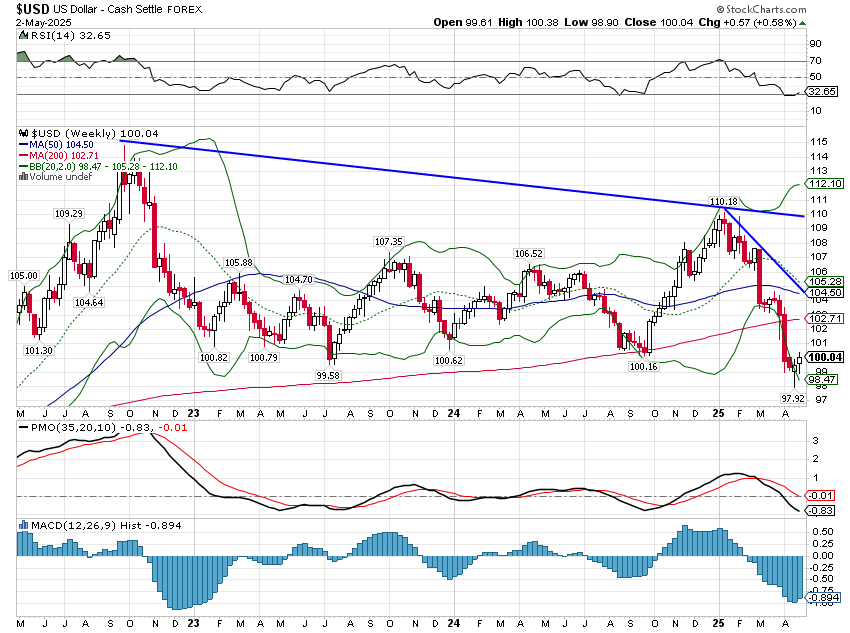

The dollar is down 8.6% since President Trump’s inauguration, almost exactly mirroring Nixon’s Smithsonian Agreement devaluation. The administration has also imposed a 10% tax on all imported goods (along with some other, higher and more specific levies), again, just as Nixon did. President Trump is also trying to get Congress to pass tax and spending cuts, just as Nixon did. President Trump has said, repeatedly, as Nixon did, that the remedy to higher import prices caused by tariffs, is to buy American manufactured goods. Nixon’s policies were largely liked domestically initially, as Trump’s are, and utterly shocked our allies, as Trump’s have. One could also point to Nixon’s pursuit of trade deals with the Soviet Union (yes, you read that right) and China, just as 50 years later President Trump also tries to neutralize US foes through trade negotiations.

The breakup of the Bretton Woods monetary system of fixed exchange rates was predicted by Robert Triffin as early as 1959 and Keynes had identified the same flaw in 1944. In many ways, Nixon had no choice but to end Bretton Woods when he did, but it was, in a sense, doomed from its inception; it was only a matter of time. The floating exchange rate “system” that emerged in the wake of Nixon’s shock retained some of those flaws but, at least in theory, market-determined currency values should adjust to correct long-term trade imbalances. But that is true only for countries (or common currency areas such as the Euro) who allow their currency to truly float, for its value to be determined by the market. Markets can, of course, misvalue currencies because markets are nothing more than groups of people who act on emotion rather than being purely rational. But markets will get things right a lot more often than governments who think they know better.

The Triffin dilemma was cited by Stephen Miran in his paper of last November, A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System, but we no longer live in a Triffin world. Arguably, we did exist in a similar environment from 1994 to about 2008 because the Chinese Renminbi was pegged to the dollar at an artificially cheap level. That required the Chinese to accumulate dollars because of the capital inflow to its emerging economy from US and European offshoring and they gained manufacturing market share by keeping the currency cheap. Today the Chinese currency is still not free floating and the Chinese have no intention of allowing it. To do so would require the free flow of capital into and out of China and the likely result would be a large outflow from Chinese nationals trying to preserve the wealth they’ve built up over the last several decades. Today, China is no longer accumulating dollar reserves and has to support the value of its currency.

The gist of Stephen Miran’s plan to reorder the global trading system is that the cause of global trade imbalances – which certainly do exist – is an overvalued dollar. The vast majority of the 41 page paper is nothing more than a review of the available options for correcting that overvaluation. The Trump administration hasn’t followed his plan exactly but we know that the President, Vice President, and Treasury Secretary have all expressed support for a cheaper dollar. We also know the administration believes tariffs are an essential part of its economic plan and expectations that they will all be rolled back as trade deals get done are likely unrealistic. Unfortunately, while the dollar is likely somewhat overvalued, it isn’t the main source of the recent expansion of our trade deficit. That falls to our budget deficit and based on the budget plan working its way through Congress, deficit reduction seems unlikely.

50 years ago, a US president tried to restructure a global trading and monetary system he believed was no longer beneficial to Americans. Today, President Trump sees the world in largely the same terms and also seeks to restructure global trade for the benefit of America. President Trump is following, almost exactly, the same plan laid out by President Nixon a half century ago. The results of the Nixon shock were so bad the economics profession had to invent a new word to describe it – stagflation. There are a lot of differences between today and the 1970s so I can’t say for sure that the outcome will be the same, but there are more than enough similarities to warrant concern.

Fortunately, if we do continue down this Nixonian path toward a cheaper dollar, we have the experience of the ’70s to guide our investments. When Bretton Woods ended and the dollar was set adrift, investors had no guide because the dollar had always – well almost always – been tied to gold. The shockwave of that change reverberated throughout the entire decade of the ’70s. But this time around, we have not only the ’70s but two weak dollar periods since then – 1985 to 1993 and 2002 to 2008. The end of both of those periods included a banking crisis (the S&L crisis in the early 90s and the 2008 financial crisis) so experience doesn’t guarantee a good outcome but we Americans always seem to find our way back to prosperity and we will again. We will try the easy things first, like devaluing the dollar, but in the end we will, to paraphrase Churchill*, do the right thing after all the other options are exhausted.

*There is no known source for this common Churchill quote but if he didn’t say it, he surely should have.

Environment

Stocks have made a remarkable comeback from their April lows but the dollar has not. While stocks managed a 3% gain last week the dollar managed to eke out a mere 0.5%. Absent any bad developments on the trade front, I would still expect a near-term rally just because everyone has become so negative recently. A short-term target would be around 102-102.5 and it could stretch up to about 104. The dollar is in a short-term downtrend that is now about 4 months in length and I fully expect it to turn into a longer term downtrend over time. But no market moves in a straight line and this one won’t be any different. My intermediate downside target is around the 90 area where I’d expect strong support. What fundamental developments take us down there I can’t say but I’m sure it will be so obvious when we get there that everyone will wonder how anyone could have missed it. It does seem a lot easier to think of reasons for the dollar to go down right now than up and if I know that, plenty of others do as well, so don’t press your cheap dollar bets too hard just yet. The character of the bounce – or the lack of one – may give us a clue how everyone else feels about it.

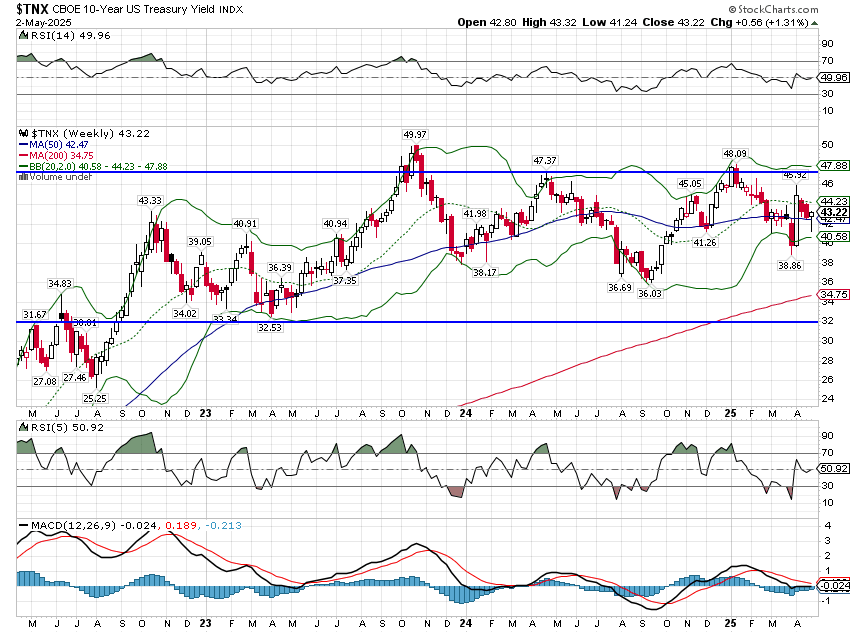

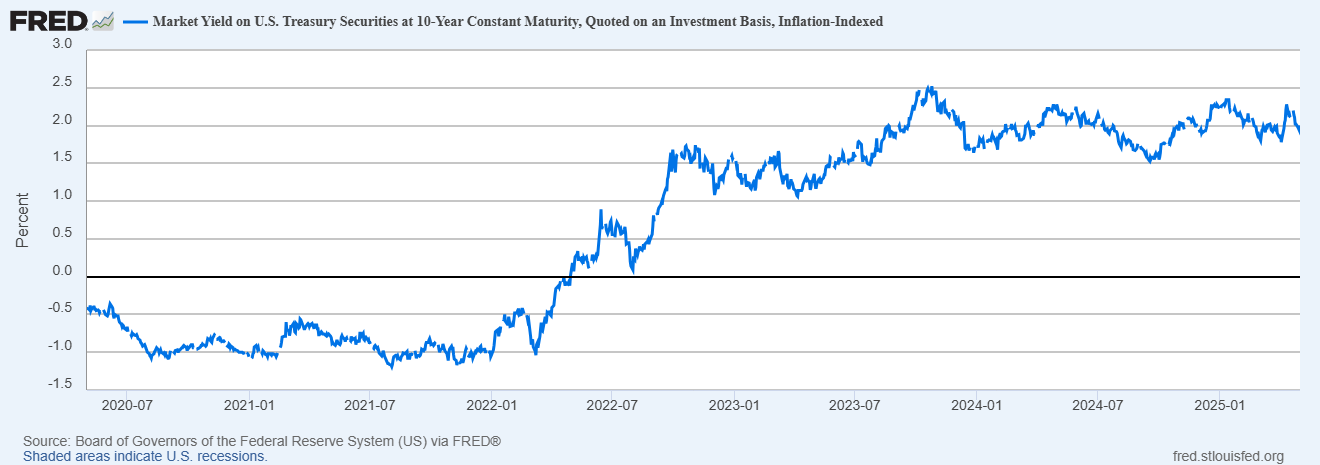

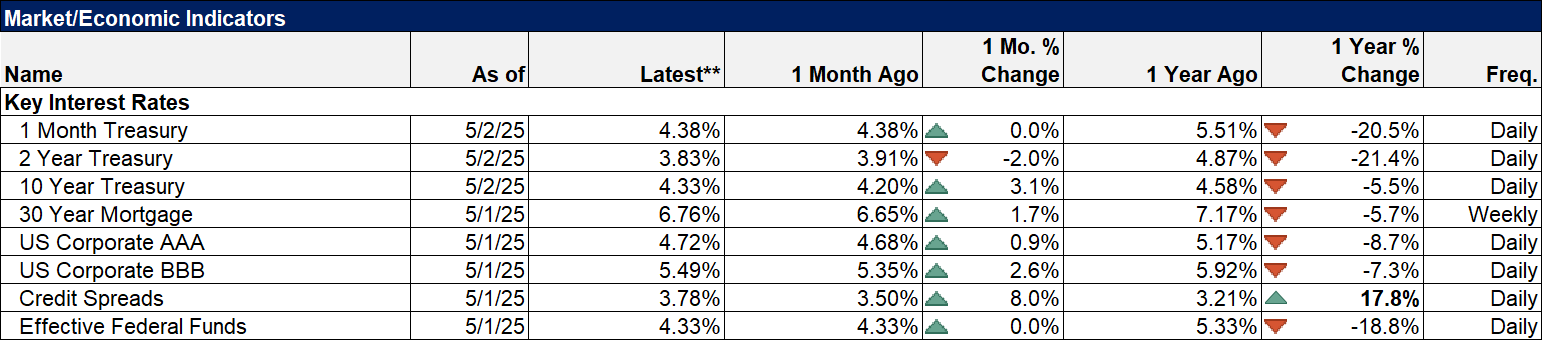

Interest rates were up last week but the 10-year rate remains in the upper portion of the range that has existed for nearly 4 years. With the 10-year TIPS yield tracking the nominal 10-year yield tick for tick, there is essentially no change in real growth or inflation expectations this year. The nominal 10-year yield is down 15 basis points this year while the 10-year TIPS yield is down 17 basis points. There is a loud chorus of recession calls right now but markets just don’t agree. That could certainly change but if that’s your call right now just be aware there’s a lot of money betting that you’re wrong.

Markets

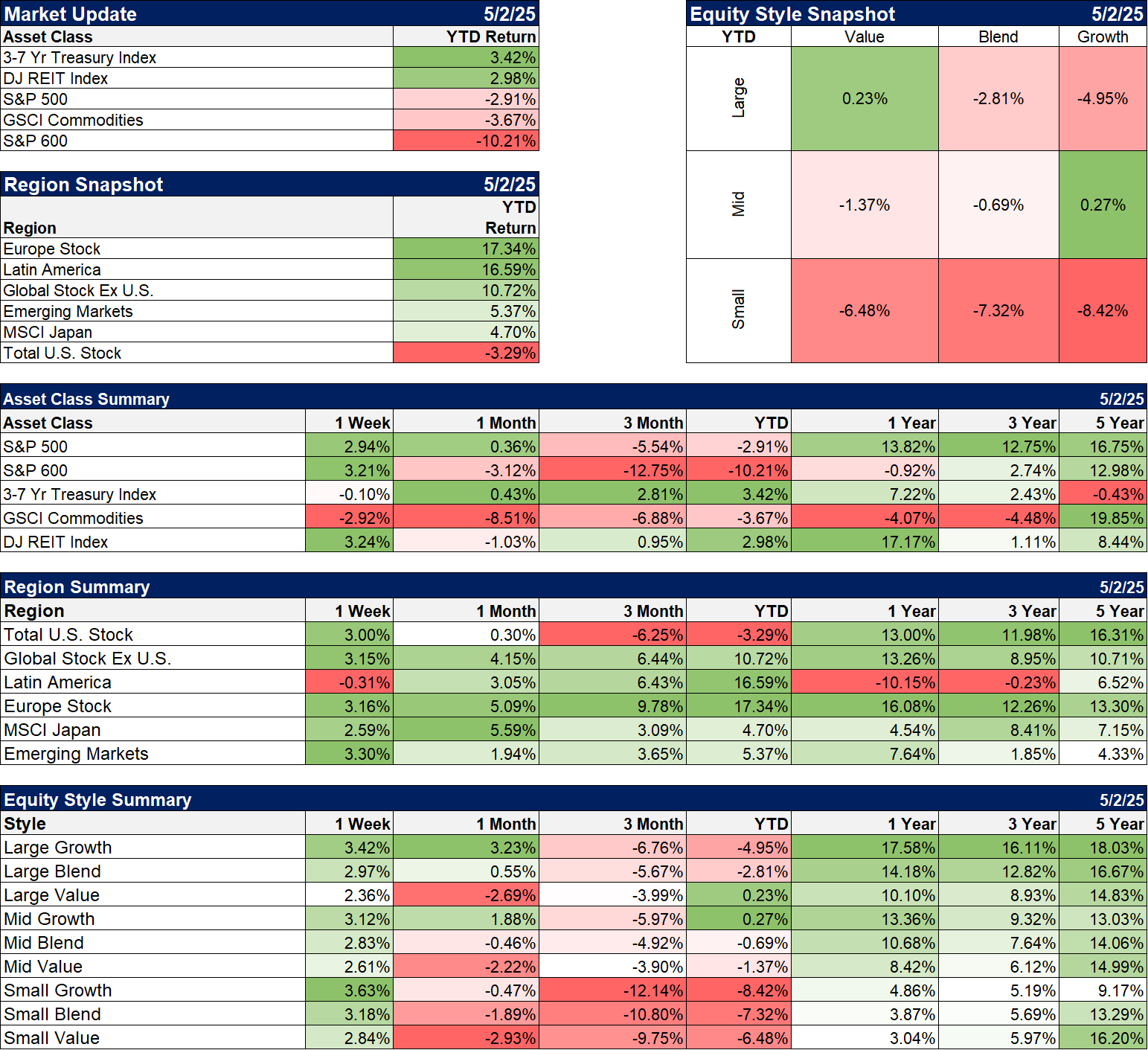

US stocks had a good week but it is interesting that foreign stocks still managed to best them by a little. The market seems to be saying that the trade war, however it is resolved, will be better for the rest of the world than the US. If one assumes that the US becomes more protectionist and the rest of the world less, then I think that makes perfect sense. Whatever investors are thinking, US stocks are down on the year (Total US stock which is Large, Mid and Small caps) while non-US stocks, particularly Europe and Latin America, are soaring.

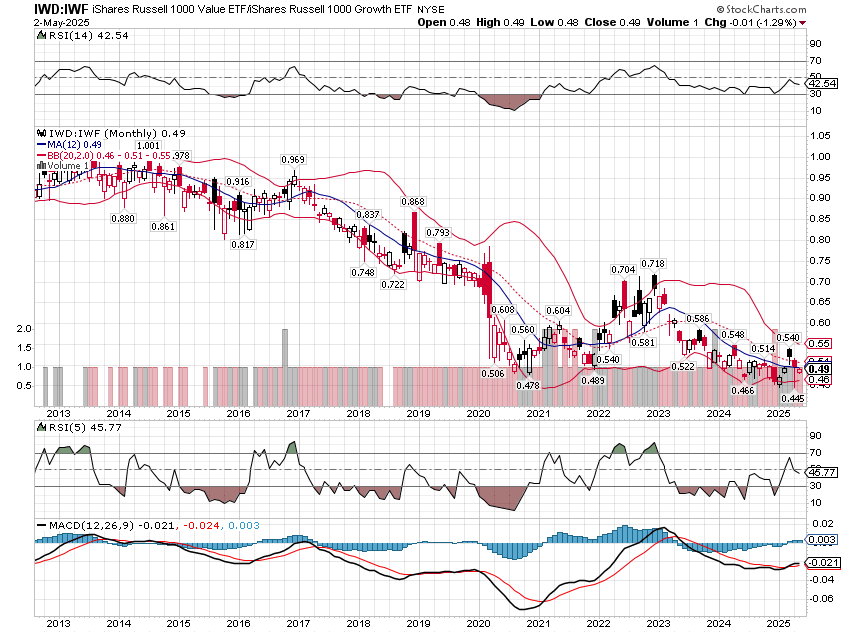

Value and dividend stocks (not shown) continue to outperform this year and they are rapidly catching up on a one-year basis. Is this finally the turning point away from growth? If so, it isn’t evident from this chart of Russell 1000 value vs Russell 1000 growth. Maybe the period since late 2020 to today was part of a bottoming process but you sure can’t say that right now.

Sectors

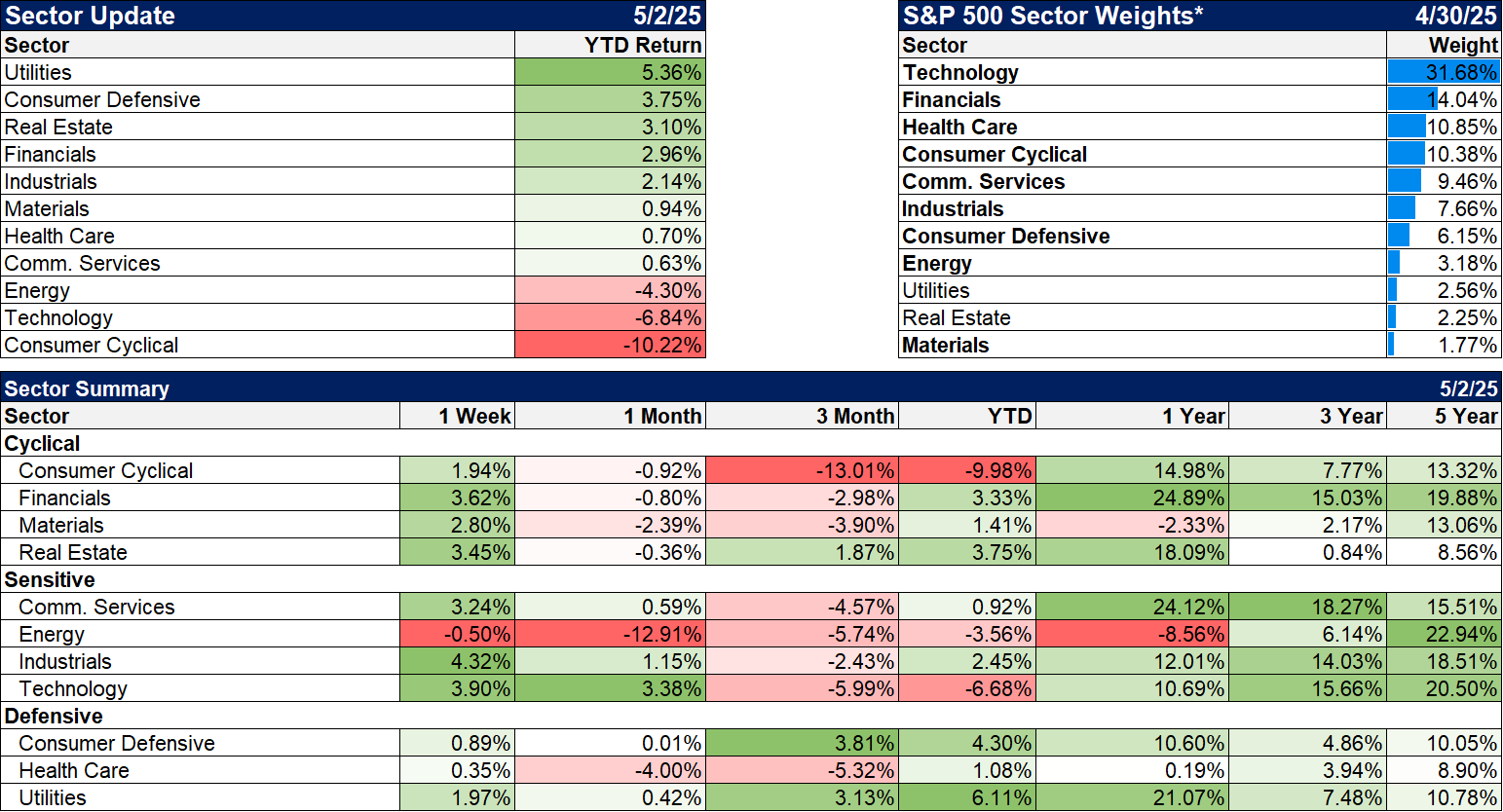

The only sector that ended the week in the red was energy which is also the worst performing sector over the last year and fourth worst over the last 3. Even after all that, it is still the best performing sector over the last 5 years, beating even technology. With sentiment on oil prices right now about as bearish as it gets, I suspect the underperformance won’t last much longer. Monday should be interesting with OPEC+ meeting to decide whether the ramp up production targets again. Interestingly, they haven’t done so since they agreed to a few months back. US inventory at Cushing, at 25.7M is well below the 10-year average of 42.9M. The average back to 2004 is 35.7M. The futures market remains in backwardation too with front month crude at a premium of $1.26 over the December contract. That doesn’t sound all that bearish to me. With everyone expecting crude to fall, maybe it’s time to get contrarian.

Economy/Market Indicators

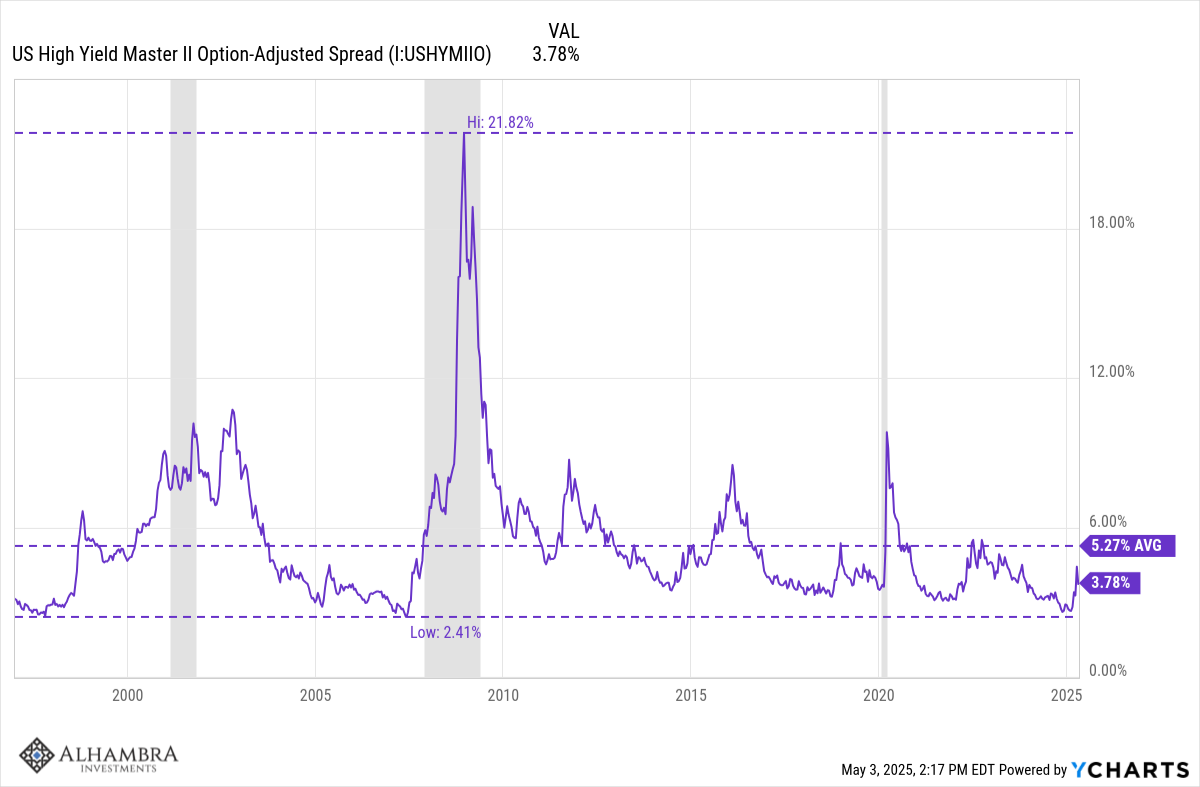

Credit spreads remain slightly elevated and have not shown the same resiliency as stocks. Still, spreads are less than the long-term average and don’t signal any threat yet.

Economy/Economic Data

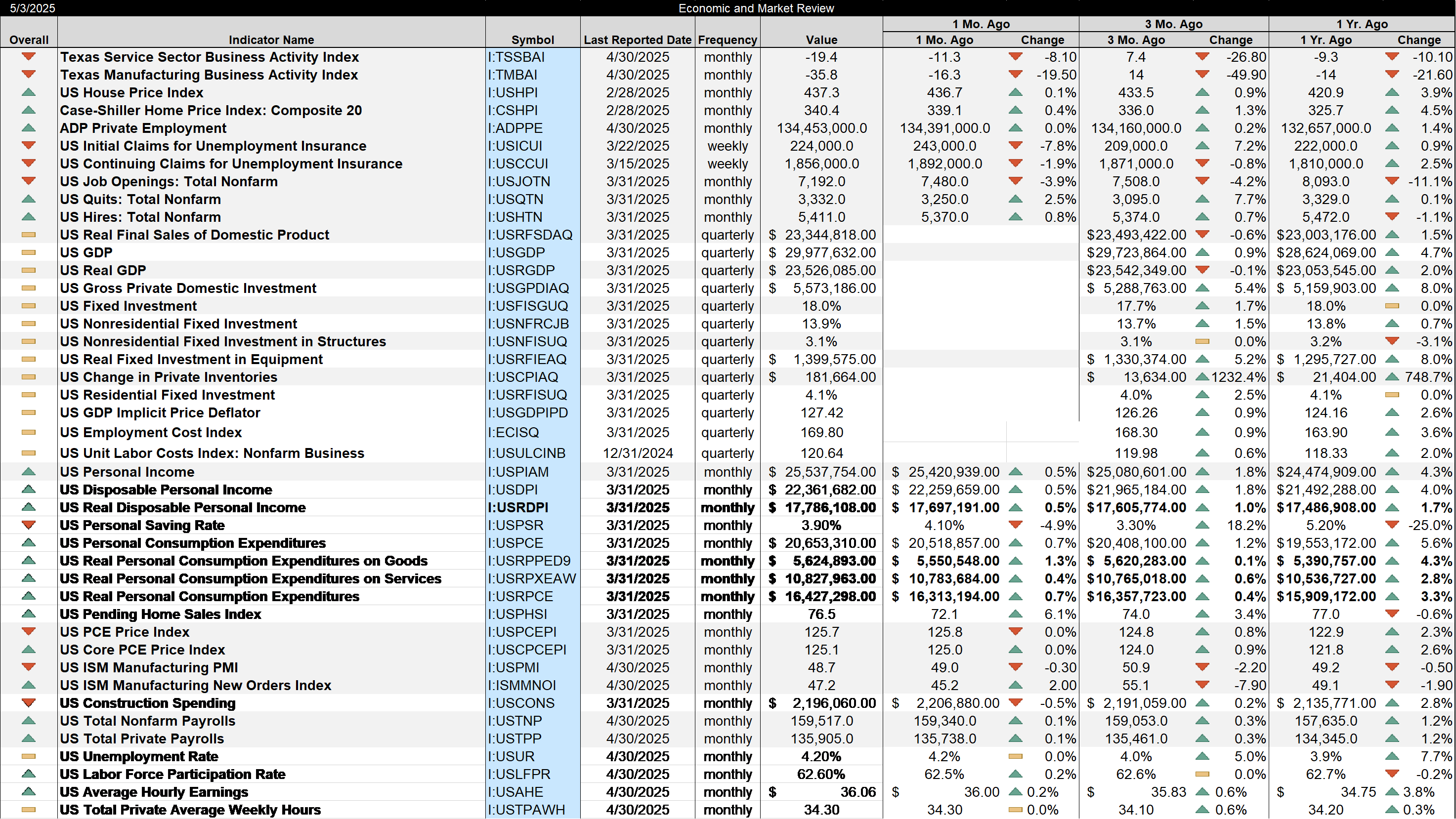

There was a lot of data last week but nothing that really stands out as all that surprising. Most of the data being reported right now is from March and so doesn’t reflect any change after “liberation day” on April 2nd. The only exceptions are surveys from the regional Feds and the ISM. Those are softening of late but given the surge from front running the tariffs that isn’t surprising in the least. And frankly it isn’t that much different than where it was a year ago. The April ISM manufacturing survey, released last week, was just 0.5 less than a year ago (48.7 vs 49.2) and neither reading is recessionary.

Q1 GDP was reported as -0.3% and there were plenty of people claiming that was due to tariff front running but I don’t see it that way. There was certainly a surge in imports but that doesn’t, despite widespread misunderstanding, make GDP worse. Net exports are a negative in the GDP calculation because we’re trying to measure Gross Domestic Product. Since consumption and investment in the other parts of the equation include imports, we have to subtract them out to find domestic consumption (production). Inventories, by the way, are included in the investment part of the equation. What that means is that whether the surge in imports was consumed or put into inventory doesn’t matter; it is neutral to GDP. So, the negative GDP print was real but as I’ve said many times over the years, wait for the revision. Inventories and trade are both estimated for the first iteration of GDP because we don’t have the actual reports yet for March. My guess is that this quarter will be revised higher when we get the second and third estimates.

I won’t go through all these reports from but I’d urge you to take a look at the last column, the year-over-year change.

Stay In Touch