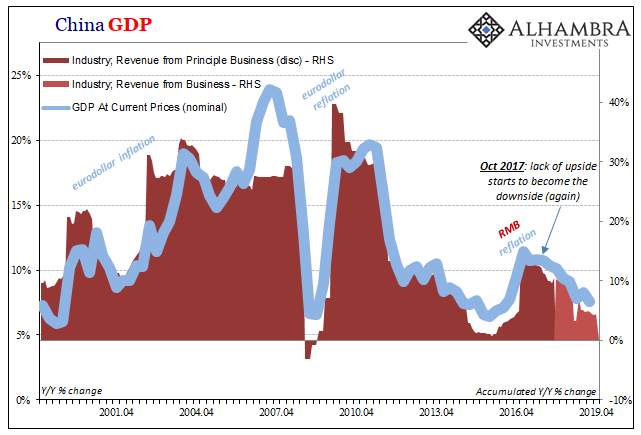

It has been perhaps the most astonishing divergence in the first two decades of 21st century history. In late 2017, Western economic officials (mostly central bankers) were taking their victory laps. They took great pains to tell the world it was due to their profound wisdom, deep courage, and, most of all, determined patience, that they had been able to see their policies through to the light of day (no thanks to voters around the world).

This set up the third decade of this century for a return to normalcy in sharp contrast to the deep struggles throughout its second. Before he was nominated as President Trump’s pick to replace Janet Yellen as the Federal Reserve’s Chairman, FOMC Governor Jerome “Jay” Powell summed up globally synchronized growth as only he could. This was October 12, 2017:

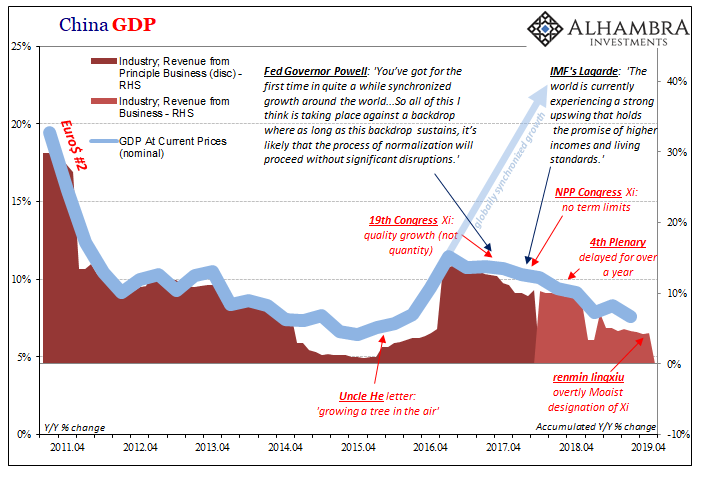

You’ve got for the first time in quite a while synchronized growth around the world, you’ve got a dollar that is flat to down, you’ve got commodity prices up, and you have really significant reduction in downward pressure on the Chinese currency. So all of this I think is taking place against a backdrop where as long as this backdrop sustains, it’s likely that the process of normalization will proceed without significant disruptions.

He has the unusual knack for picking out all the right factors for his analysis, and then combining them with orthodox practice so as to only heighten the eventual confusion (when all those things “unexpectedly” turn against him but he sticks with his prior view anyway).

At nearly the same time future Chairman Powell was singing the praises of globally synchronized growth, on the other side of the world an actual Chairman, Xi Jinping, was whistling a very different tune. A country who depends most on the whims of the global economy, China’s Communist Party boss wasn’t seeing what Jay Powell was seeing even when looking at the very same things.

At the 19th Communist Party Congress, which kicked off a week after Powell’s speech, Xi’s keynote was darkly portentous. You can easily find a Chinese version of his speech and read any translation of it for yourself; for our purposes here you’ll have to suffice with my contemporary summation of it:

But what Xi was actually saying was really nothing like “make China great again”, merely an emotional plea in the same economic manner as the American’s campaign. The word rejuvenation that he used repeatedly (in its translation) actually meant in the context of Xi’s speech something very different, more like “make China OK with not great.”

Xi proclaimed a “new era” where the quality of growth would be the priority over quantity or speed. It sounds good until you think about it, as anyone with common sense knows that quality comes from speed. The rejuvenation part was nothing more than making it seem as this was the plan all along; the official version of “oh, hey, we meant to rebalance this whole time.” Only there isn’t any hint of rebalancing.

Two very different views of the world heading in very different directions at an incredibly momentous moment in world history.

Powell’s the one with the fancy Economics pedigree, though. He’s been called an outsider but he has operated every bit the typical central banker in talk and action. You would think, given how we are constantly reminded that central bankers are those everyone is supposed to turn to on these questions, the Fed’s leading man would have trounced China’s on this one central topic.

You already know that wasn’t the case. While Powell has been pushed into stuttering and confused positions, one after another, Xi has been unequivocal and perfectly consistent this entire time. The one operated under the illusion of globally synchronized growth, while the other saw right through it to what that might really mean for his own otherwise precarious position.

Powell didn’t expect this globally synchronized downturn while Xi has been practically waiting on it.

At the end of 2019, two years of confusing misdirection later, we’ve encountered the latest in the string of diverging perceptions. While no longer championing the robustness of whatever globally synchronized growth could have been, in the typical central banker’s mind, Powell clings to the notion that the global economy might generally be fine anyway.

To which the Chinese government continues to act against that view in open defiance. That’s really the object lesson of the last few years of this decade. Listen to the central bankers delude themselves into fantasy, and then marvel but only in the sheer entertainment value of it. Take none of it seriously.

But pay very close attention to what the Communists of China are actually up to in order to track the real position of the global economy while you do.

From what I can tell, the term renmin lingxiu hasn’t made a dent in Western discourse, politics as well as economics (small “e”). That’s a real shame because it is another one of those government deeds that people paying attention in the way I describe in the paragraphs above will look back on and appreciate for how things likely will have turned out. An important signpost on the descent.

The Chinese phrase renmin lingxiu translated literally means “people’s leader” (just like renminbi is, or is called, the people’s money). Having placed “Xi Jinping thought” into the Communist constitution last year, removed all limits in his three top echelon positions (party, military, state), the Politburo this week now hails Xi Jinping using these words which were undoubtedly meant to echo Mao Zedong.

It was in the late seventies, after Mao (and his wife, Jiang Qing, and her Gang of Four), that Deng Xiaoping put in place these restrictions intended to prevent a recurrence of the cult of personality that had led to some of China’s (and humanity’s) darkest moments. It had been exclusive fealty to Chairman Mao, the absolute prohibition on any dissent even at the top, which had unleashed first the disastrous (monumentally stupid) Great Leap Forward followed by the Jacobin purges of the Cultural Revolution.

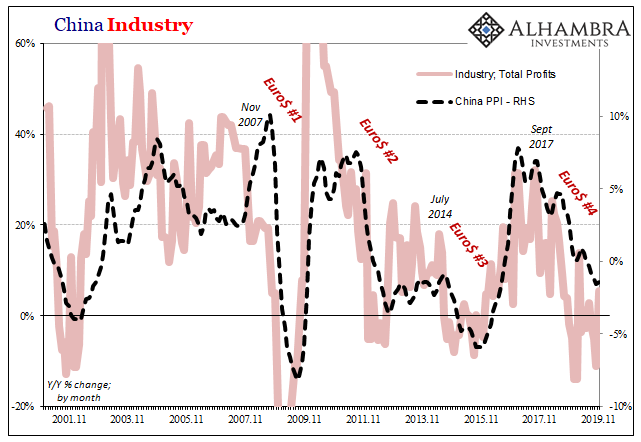

Ever since late 2017, three things have happened simultaneously: Western central bankers have continued to embarrass themselves about the global economy; China’s Communist leadership has proved more and more dangerously reactionary; and both have been predicated on a global economy caught falling back down at the very time it was supposed to have picked itself all the way back up.

As China’s latest economic data can attest, renmin lingxiu is a straight up ominous way to end this decade and begin the next.

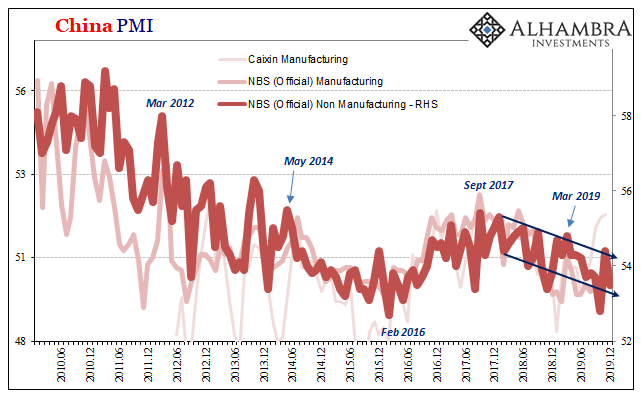

Of those figures, they are the same you’ve seen before all during the past two years. The National Bureau of Statistics reports that the manufacturing version of its PMI stayed flat at 50.2 in December 2019, while the non-manufacturing index “unexpectedly” declined from a multi-month high reached in November. At 53.5, the latest reading merely a continuation of this year’s and last’s dominant trend.

Recent figures on China’s vast industry, the sector that still runs the Chinese economy, have pointed in that same direction. Industrial Revenues were up just 4.4% (accumulated) year-over-year through November, while total profits fell by 2.1%.

The current end-of-year conundrum centers around the direction for the global economy, though more optimistic of late still highly uncertain – at least that much has improved from 2017 when everyone was unified in their mistake. Much of that, however, rests upon the opinions and “expertise” of those central bankers like Jay Powell who have a knack for identifying the right factors though possessing no earthly idea why they are so important (or what makes them lean one way or another).

And while Powell reassures us everything is fine, China’s Communist leadership continues to act in the expectation of more of the same at the very best like the last couple of highly insufficient years.

Same planet, very different worlds. But only the one global economy.

The 2010’s were scheduled to end on a high note. The decade most decidedly did not, as only the one group of actors – the wrong ones, I might add – figured in advance. Instead, the 2020’s begin under even greater suspicion because the Communists are so much better at reading economics than all the West’s prematurely-celebrated Economists.

Rather than end the decade on such a decidedly dejected and sour note, I will add that I remain deeply optimistic (yes, you read that right) about the long run – maybe even the 2020’s. Once the world stops listening to Economists and central bankers on any topic, and starts to pay attention to what the Communists are up to, what will follow should be one of the most inspiring periods of economic growth in modern human history. All the ingredients are there, save the one (that little something about the dollar).

Maybe that puts us just a little closer to that potential upside, in the grand scheme of things, though the world right now continues to sink, slowly, in the wrong direction.

Stay In Touch