It is absolutely amazing the lengths people will go to in order to deny the most straightforward and obvious explanation; to torture and twist plain evidence. That’s the thing about rationalizing, though. The narrative usually matters more than the facts.

Take tax reform and interest rates. The problem with tax reform wasn’t actually tax reform. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) was chock full of good and reasonable ideas, measures that were desirable on their own merits.

Beside the government “allowing” you to keep more of your own money, the law also encouraged pension funds to do something about their chronic and growing shortfalls. Everyone knows that retirement plans have been depending upon fuzzy math related to investment returns (which can’t be predicted) to keep within even fuzzier guidelines about solvency.

The TCJA encouraged companies to actually set aside real reserves in order to at least partially and somewhat address this pretty hazardous reality. They were given a tax break: though the corporate tax rate was reduced to 21% from 35% as a result of the law, businesses with qualified plans would still be allowed to deduct pension contributions at the old rate.

Many of the world’s biggest firms did just that. A flood maybe even a deluge of new money headed into the portfolios of institutional pockets. And with these new funds there was demand for the safest assets; very much like insurance reserves, a large proportion of pension reserves are tucked away into UST’s and the like given their risk-averse core nature.

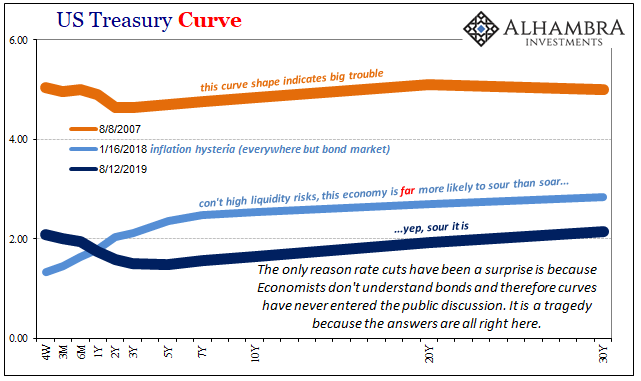

The tax break was scheduled to expire in September 2018. Naturally, given what was going on in 2018 this was seen as a huge deal – for the bond market; or, more precisely, because of what wasn’t going on. Everyone said interest rates had nowhere to go but up, and while they were rising they weren’t rising very fast or very far at the long end. The curve had flattened out dramatically.

It was signaling a warning at a time when there seemed no reasonable basis for one.

Jay Powell had said emphatically that inflation and accelerating economic growth were going to pressure bonds – a good thing, all things considered. Under the guise of the looming BOND ROUT!!!, this tax quirk seemed to many as a good explanation for why the curve had flattened when it shouldn’t have given the economic fundamentals as described uniformly by central bankers, Economists, and the mainstream media (redundant).

The apparently artificial pension-driven demand for longer-dated bonds would dry up in the middle of September. Then BOND ROUT!!!!

“One of the most powerful forces in the market place is this pension buying that is taking place,” said Tom di Galoma, a managing director at Seaport Global Securities…

“Every day for months now there has been steady buying of 30-year Treasuries,” said a trader at one large bank. “That goes away after September.”

As the 30-year bond comes within sight of its record low yield today, obviously that wasn’t the case. The idea of tax reform explaining demand for UST’s was little more than rationalizing. Because the myth of central banks and QE just won’t die, otherwise normal and intelligent people are left with increasingly bizarre and absurd stabs in the dark for why what is plainly obvious just cannot be true.

Pension reserves sounded plausible; liquidity fears never do, certainly not with all those trillions in bank reserves that the Fed skillfully added with four QE’s. It can’t be the bond market acting on survival instincts because why would anyone be concerned about such things after years and years of money printing – and the obvious success of so much money printing which is why interest rates had nowhere to go but up.

It was two intellectual leaps folded into one giant case of disbelief; UST demand due to rising liquidity fears would mean QE and bank reserves aren’t what everyone believes they are, and it further would mean the economy isn’t recovering when everyone said it was already booming.

Imagine “everyone’s” shock over the trend in interest rates since last November. If the bond market was clearly artificial for technical reasons before September 2018, there surely must be other even more compelling explanations for why in early 2019 lower yields are absolutely guaranteed to be transitory!

At the end of March, Bloomberg offered one, a different rationalization:

The Federal Reserve’s surprise policy shift last week shook markets, but, even still, the intensity of the ensuing drop in U.S. bond yields has puzzled many observers. A massive wave of hedging in the swaps market helps explain the scale of the eye-catching move.

Portfolio managers especially those invested in MBS were caught wrong-footed by the direction of interest rates, supposedly. They had believed the BOND ROUT!!! was coming and when it didn’t they had to do something about duration and negative convexity (don’t ask, it doesn’t really matter).

In other words, it was a technical-sounding answer to why interest rates were moving the wrong way and quickly. Once MBS managers had repositioned their duration risks, so the thinking went, then this “artificial” interruption would dissipate and the bond market would start behaving the “right” way again.

Except, obviously, it hasn’t. Because convention has it all backward from start to finish, the effect is always confused as the cause. Treasury (and swap) rates weren’t being pulled downward by excess hedging, there was excess hedging being triggered by interest rates moving downward for their own reasons.

Liquidity risks are and have been rising. It is that simple but, again, for much of the conventional landscape this is an impossible development.

Once you get past that myth, once you translate the world into its reality outside the myth, you don’t need to desperately search for the next flavor-of-the-month benign sounding technical excuse. Falling bond yields are exactly what they appear to be.

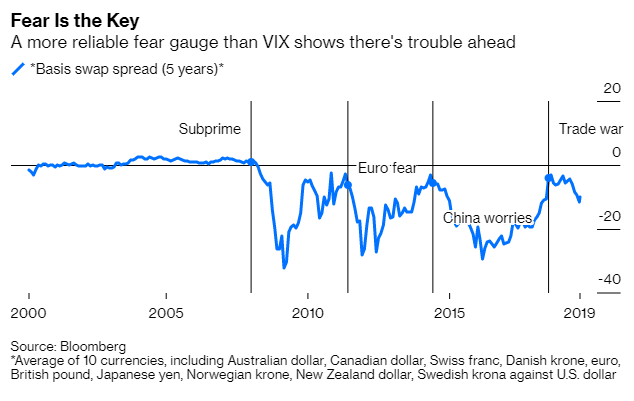

One of the last big indications which would fall into this category is the global dollar basis. It’s like a ripple of waves eventually spreading out across the entire surface of what had been, and was supposed to be, an otherwise calm body of water; or an infection that begins localized before spreading the disease into the vital organs of a susceptible individual. Despite the doctrine and acceptance of “abundant reserves”, we now have basis swaps (and mainstream acknowledgement) confirming bond yields:

Theory says there should be no such dearth of dollar funding obtained synthetically, but since the 2008 crisis there’s a scarcity that comes and goes, signaling fear ahead of rockiness in the global economy. Right now, the dollar squeeze isn’t awful, but it’s worsening, with implications for everyone from Japanese banks and South Korean insurers to the Indian government.

This dollar scarcity comes and goes, alright, and for longtime readers you’ll immediately recognize the pattern and the timing:

Only, it wasn’t subprime, it wasn’t “Euro fear”, and those China worries were created because of the same thing as those two before it. The bond yields and basis swaps of 2019 are moving in the wrong direction, true, but it’s not trade wars, either.

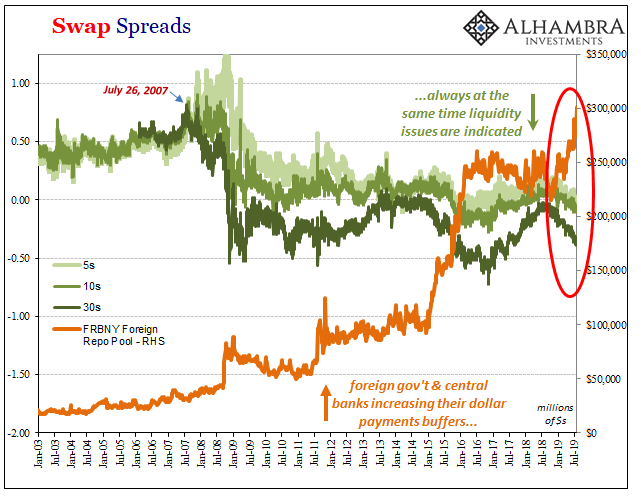

What is a cross currency swap and what does a negative basis for it really mean?

The negative yen basis swap acts like leverage where even yields on the interim “investment” are negative. Any speculator or bank with spare “dollars” could lend them in a yen basis swap meaning an exchange into yen. Because you end up with yen you are forced into some really bad investment choices such as slightly negative 5-year government bonds, but that is just part of the cost of keeping risk on your yen side low. Instead, the real money is made in the basis swap itself since it now trades so highly negative. The very fact of that basis swap spread means a huge premium on spare dollars; which is another way of saying there is a “dollar” shortage. Because of the shortage and its premium, you can swap into yen and invest in negative yielding JGB’s in size and still make out handsomely.

These are huge potential returns embedded in a negative basis (especially averaged across all the major currencies). The fact that it can get so negative to begin with tells you that there aren’t enough takers for the other side, the fat side of the trade – those with “spare dollars” which is really just balance sheet capacity. The fact that it persists for long periods of time means something other than temporary, the very condition that would drive market participants more and more into UST’s no matter how many times they are assured by all the right people to never fight the Fed because there’s nothing but curious trivia setting the market.

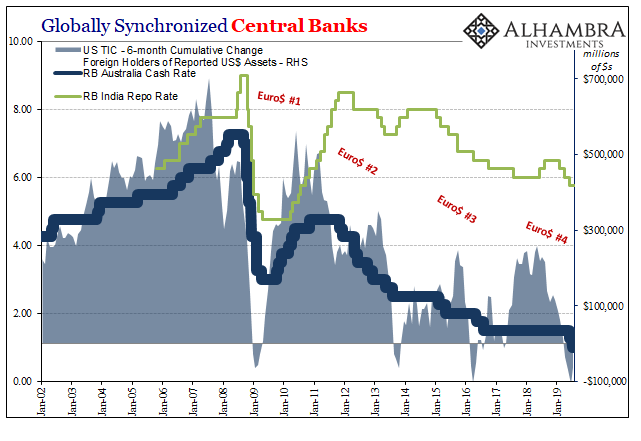

But it’s not just basis, is it? It is the consistency across so many definitions and market prices, data and indications. They all say the same thing and at these same times. Nobody can make out where they are saying because it’s a very different language than what is spoken in the mainstream.

The two most important takeaways: they really have no idea what they are talking about, meaning central bankers, Economists, and the vast majority of the financial media; more importantly, liquidity pressures really are escalating globally.

Not that we needed any more confirmation. If the world hadn’t been fooled into blindly following central bankers, to rationalize and make excuses for simple and straightforward facts, all anyone would’ve needed this whole time to perfectly understand the situation was Treasury rates and the yield curve.

Stay In Touch