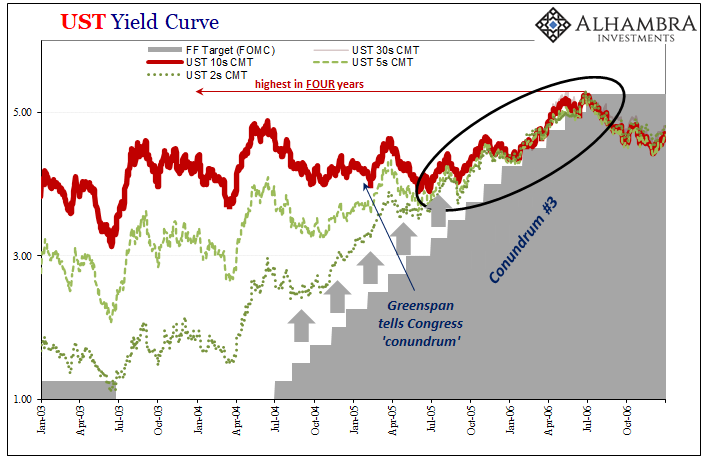

As Alan Greenspan’s rate hikes closed in, longer-term Treasury yields were forced upward as the flattening yield curve left no more room for their blatant defiance. By mid-2005, though, the market wasn’t ready to fully price the downside risks which had already led to that worrisome curve shape (very flat). While all sorts of bad potential could be reasonably surmised, none of it seemed imminent or definite.

Thus, between July 2005 and June 2006, the entire curve was lifted up by the combined rate hikes of Greenspan then Bernanke. The Federal Reserve remained convinced that economic risks were decidedly tilted toward the inflationary. The 10-year UST would go on to add about 150 bps to its yield even though by market action deflationary potential, substantial deterioration was judged more and more likely.

It was only later in 2006 when the system began to exhibit unmistakable (unless you’re an Economist or central banker) signs the yield curve – like eurodollar futures – had been right all along, leading to its eventual inversion regardless of whatever the FOMC still might have wanted to do up at the front. It may have taken some time beforehand, but once the curve did it there should have been no surprise Ben Bernanke wouldn’t vote for another hike after this.

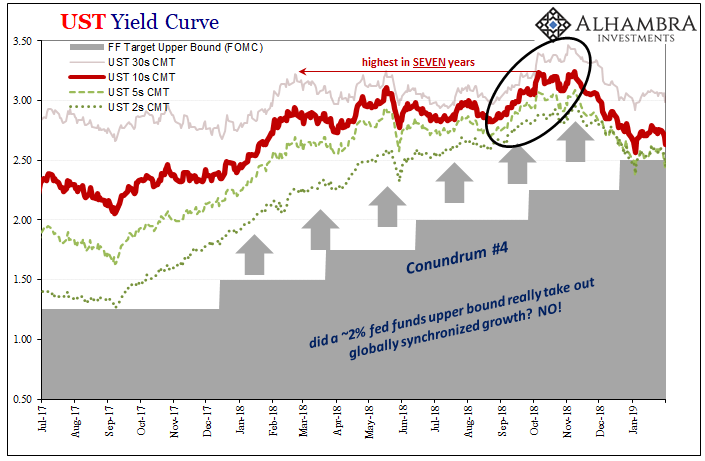

Similarly, during the next ill-fated rate hike cycle more than a decade later in 2017 and 2018, the flattened yield curve warned then, too, how the Fed was seeing the economy all wrong. Jay Powell said the risks were entirely on the inflation side though markets like eurodollar futures already had been betting heavily against this.

Eerily similar to the 2005-06 experience, the yield curve would only modestly resist the FOMC bias (flattening) for much of 2018 even though disagreement was priced more thoroughly in other places. Between late August that year and early November, the 10-year would “rout” and see its yield rise by around 50 bps – even as those other monetary and deflationary warnings had continued to grow louder and more immediate.

It was only after early November that the yield curve finally inverted, leaving a dumbfounded Jay Powell to conduct one more raise after that point – but only the one.

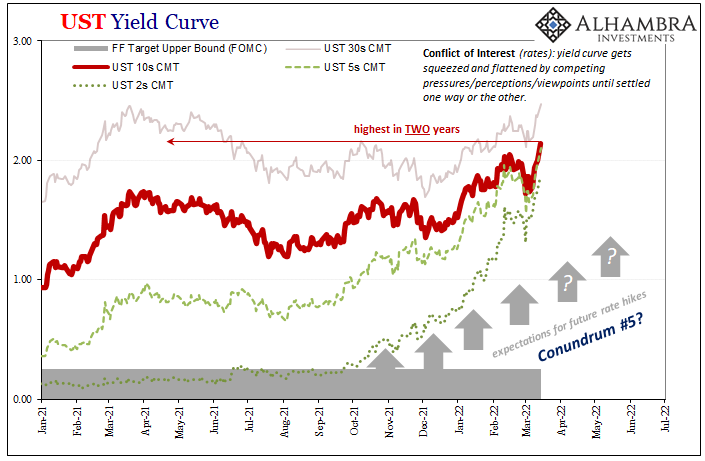

In 2022, as oil prices have mercifully plunged and fears of Russian spillover maybe temporarily abate, rate hikes have retaken center stage. Long-term Treasury yields jumped today, as they have over the past two weeks or so, with the entire back end of the yield curve being adjusted upward by expectations set by its front.

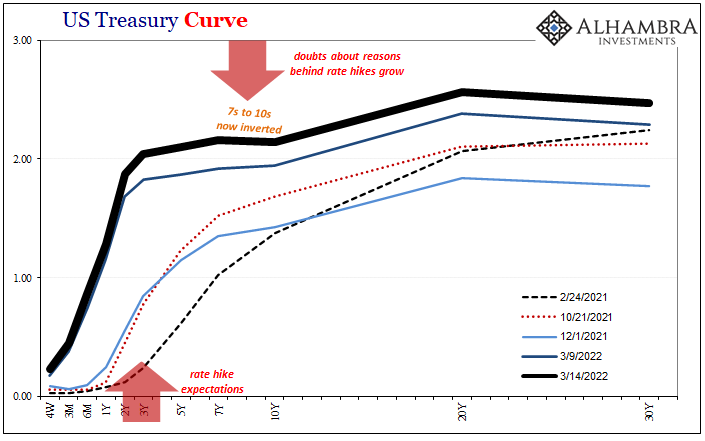

Unlike those prior cases, however, over the last two days the yield curve finds itself already inverted, oddly enough, in the 7-year to 10-year spread. Rate hike-fever may have gripped market participants at the short end, but resistance to it has only stiffened in the back despite rising nominal yields.

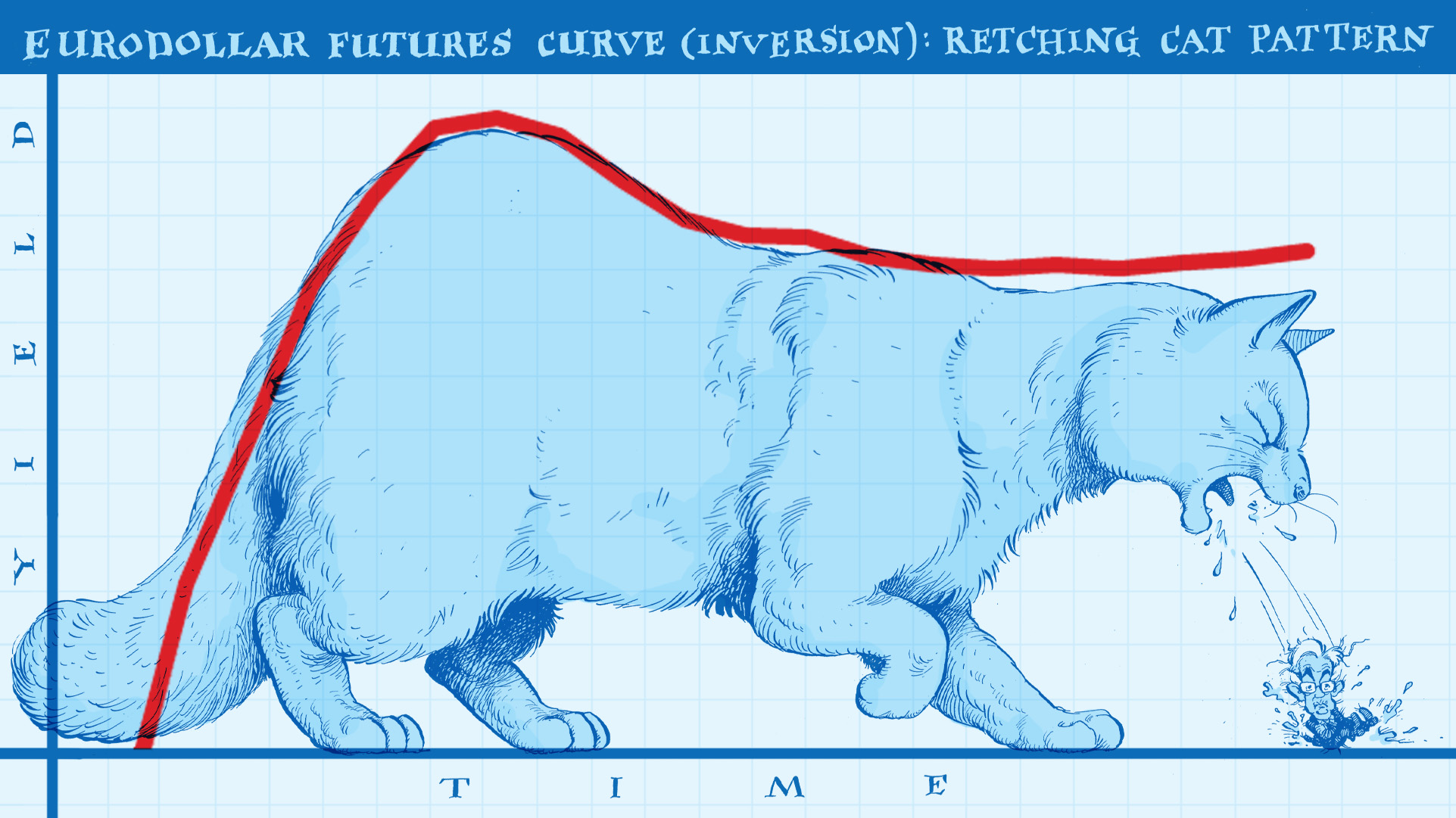

Like the eurodollar curve, the retching cat shape gets copied here.

As recent history has shown, even as deflationary potential rises throughout, it isn’t unusual to see the Fed force all rates to adjust to a higher initial frame of reference – that’s really all its rate hikes end up being. The twisting, distortion, and eventual (or already current) inversion(s) is the market becoming more and more confident this front-fed changed to the frame of reference won’t keep up for long.

Ultimately, that’s what those prior “conundrums” had been and inversion was their tipping point.

Will the 7s10s prove to be the same? Perhaps more startling, it’s upside down in that key calendar space even before the first hike of 2022 is done. The more policymakers and the media take on hawkishness, the stiffer and more obvious the disagreement in the marketplace. Even if nominal rates rise.

In fact, nominal rates always go up – before they don’t.

Stay In Touch