One month ago, on May 24, Chinese regulators stunned the world by announcing the first bank restructuring in modern China’s history. Based in Inner Mongolia, Baoshang Bank was seized because of what the PBOC and China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission said was “severe credit risk.” Initial reports attempted to link Baoshang’s struggles to financier Xiao Jianhua who disappeared in 2017.

As usual, there is always some truth in the narrative. Though much of the world had never heard of the bank before last month, the government’s appropriation was a long time coming. Baoshang had first reported a capital shortfall almost two years ago.

The question is, though, why now?

Warren Buffett famously said you only find out who is swimming naked when the tide goes out. I care much less about who has on any sort of beach apparel than the direction of the water itself. Our systemic interest is therefore backward from Mr. Buffett’s approach: only when you see the first naked swimmer do you figure out the tide’s really moving.

By tying Baoshong to Xiao, authorities are implying there’s no systemic issue. Just a random beachgoer caught on the shore in the nude. Maybe that’s the case because so much shore has been exposed by the receding waters?

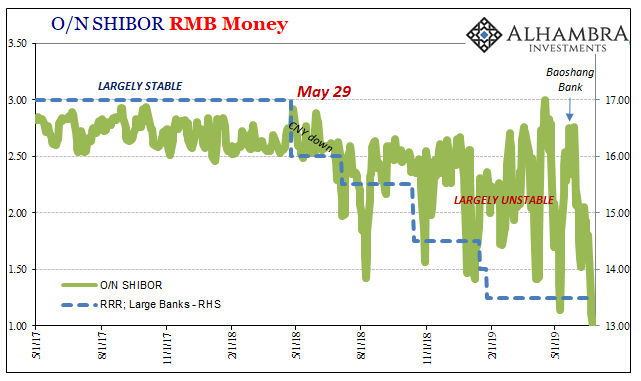

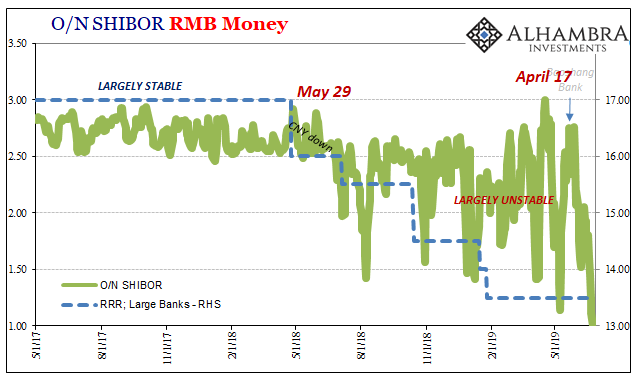

On May 8, sixteen days before Baoshong, the overnight SHIBOR rate had fallen to 1.141%, the lowest in years. Over the next seven open trading sessions, however, the rate would skyrocket an additional 161 bps; fixing at 2.75% on May 22 just two days prior to the regulatory action.

It wasn’t the first time this had happened. In fact, the O/N SHIBOR space has been on a roller coaster of volatility. The month before, in mid-April the money rate had shot up by nearly the same amount in only eight days. I wrote on April 23:

This kind of volatility especially at the shortest maturity suggests limited and temporary capacity for spare liquidity. It is the result of a titanic struggle to maintain control. The PBOC has had better success at term, but perceptions about the shortest maturity heavily color how participants act. If you think there’s a good chance you might need liquidity in a pinch, and this is what you see for overnight funding, it’s a little like volunteering for a game of Russian roulette.

The spike in SHIBOR had brought it within a few tenths of a pip shy of 3% – the highest in four years going back to eventful spring of 2015.

As of this morning, the overnight rate rests at exactly 1.00% – the lowest in a very long time. Problem solved?

Not quite. In early May, before Baoshang, the PBOC had altered the RRR for a sixth time since April 2018. Only, this one would be applied to small and medium banks exclusively; those in the same class as, it just so happened to be, Baoshang. I wrote about the that particular reserve adjustment two days before its seizure:

Enter the RRR. It is the last line of defense, the final lifeline factor which demonstrates why the PBOC has chosen this strategy. To “pay” for even a small bit of currency growth, the central bank takes away from the overall level of bank reserves. To put some of them back, it allows China’s banks to use more of what they have at their disposal; reserves long ago locked up when monetary growth was taken for granted.

It is the equivalent of an amateur, untested acrobat walking an extreme tightrope over the whole expanse of Niagara Falls.

Baoshang will not be China’s Lehman Brothers moment. It’s too small and out of the way, systemically by itself it means very, very little. What we want to know instead is what Baoshang can tell us about the tide. Has China’s systemic liquidity issues reached an important milestone such that the weakest hands are being exposed by them?

There’s already some desperation in the PBOC’s actions, beginning with the RRR for small and medium banks early on in May at the same time you know the government was involved with Baoshang. These are preventative measures, but systemic implications nonetheless.

I say systemic issues because from what we can already observe there are several dimensions to this thing. To begin with, unsecured interbank lending isn’t the only angle on this downside to liquidity. There’s been substantial repo pressures which Baoshang has revealed, too.

Just a week ago, on June 17, securities regulators in China convened a meeting of the country’s securities firms and told them to knock it off with the collateral lists. From the Wall Street Journal:

It said some institutions in the debt markets had placed certain trading counterparties on a “blacklist” and demanded they post higher-quality collateral against their borrowings. In other instances, some firms were cut off from trading because of worries that they would not repay their obligations, it said.

See, that’s the thing about repo. It isn’t supposed to matter whether you can repay the loan because you’ve already posted the collateral. Should you default the cash lender gets its cash back from selling the asset you placed in its hands. This is the whole point of repo.

But, as we’ve experienced before here in the West, the collateral factor can be its own money-like property. During the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, haircut adjustments were one of the biggest contributing factors. Lowering haircuts is the same thing as a collateral call; either put up more of the same type or find a “pristine” replacement, and if you can’t you’re done.

From the WSJ today:

More recently, he [a Hong Kong-based researcher] said some lenders required that borrowers post nearly twice the collateral for the amount they wanted to borrow—meaning that for every 100 yuan in bonds they could get about 50 yuan in cash. He added his bank is only making repo loans backed by the safest collateral, such as government securities and bonds from top-rated state lenders.

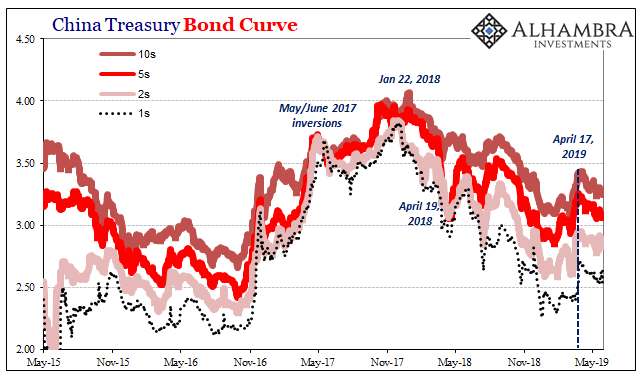

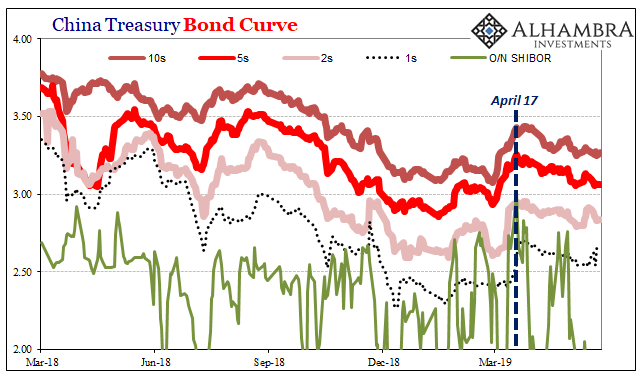

Chinese federal government bonds yields had been falling throughout 2018. As with the rest of the global bond market, the decline picked up especially in the last quarter of last year. In later January 2019, it ran into the short end of the curve.

In early April, however, bond yields were pushed sharply higher pressured especially by action in unsecured RMB (SHIBOR).

You can see the effect in late February/early March when the SHIBOR roller coaster pushed the rate up and into bond yields at the same time. The bigger one in mid-April referenced above registers in China’s bond market almost all at once. It seems to have been an enormous trigger, one that extends, or maybe comes from, beyond the Chinese border.

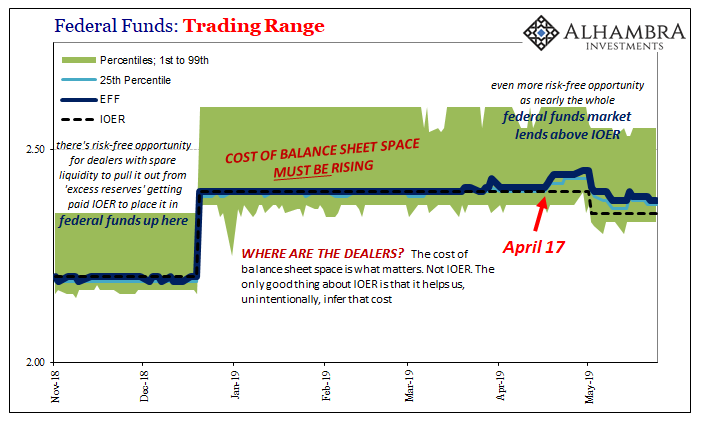

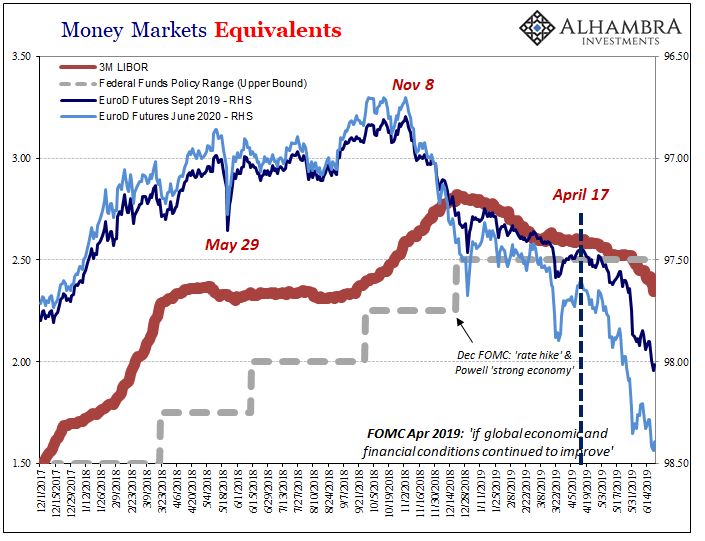

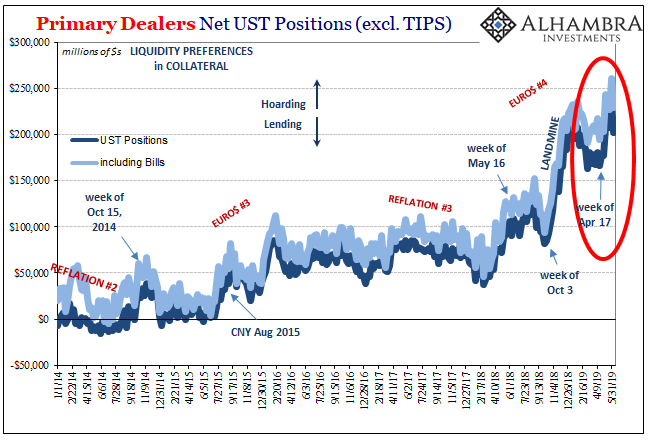

We can’t help but notice the timing: April 17. That particular date has become this year’s May 29; it shows up everywhere.

And it may be collateral which is at its center. US dealers began to hoard US Treasury securities of all kinds, bills and coupons, far more than they already had been. The UST yield curve collapsed as interest rates were pushed well below even monetary alternatives like IOER and the RRP. Almost the entire Treasury curve is now below the upper bound for the federal funds range, the 30-year long bond the lone holdout if only a mere 5 bps above (for now).

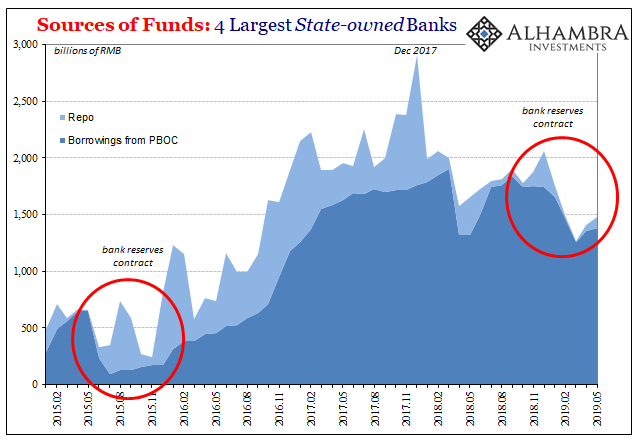

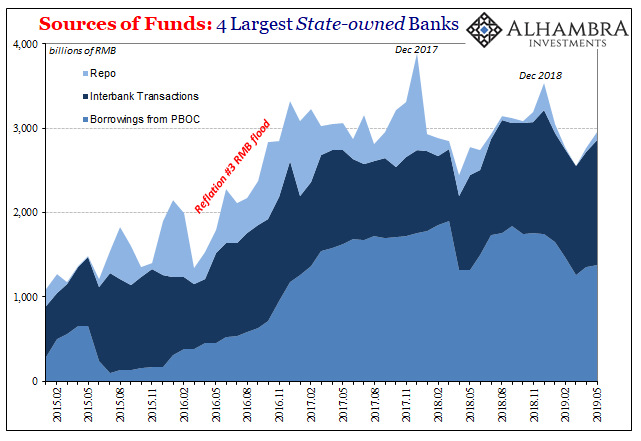

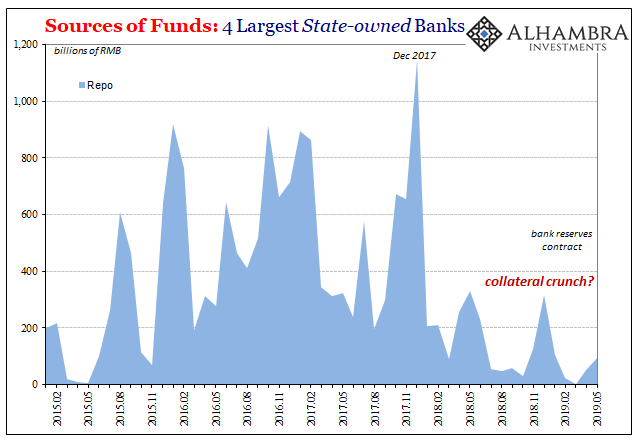

The same sorts of statistics aren’t available for US$ repo’s Chinese cousin. We are left to struggle with anecdotes and infer otherwise from tangential data. One that we have noted on several occasions especially this year is the balance sheets of China’s big four banks.

Going back to January 2018 (another month which shows up all over the world’s markets and economic data), these banks have been more and more out of repo (liabilities; or, in China’s terms, sources). Starting January 2019, they were almost out of it entirely. In fact, as you see immediately above, these same banks have been using unsecured interbank borrowing as their relief from repo (providing us with at least a partial answer for SHIBOR’s behavior).

Why?

Back in December, the PBOC had somewhat quietly arranged for banks to begin issuing perpetual bonds and further to enhance the liquidity aspects of them by starting up a bill swap program. I wrote in January:

Perpetual bonds are illiquid therefore unacceptable in repo. The central bank could take them directly at any of its windows but prefers instead to avoid having to do so. No central bank will admit that kind of risk, convoluted obscurity the official friend of the desperate.

To circumvent these technical deficiencies, the PBOC will allow banks who issue perpetual bonds (meeting further requirements, such as capital adequacy, loan delinquencies in its book, size, as well as profitability; the central bank does not wish to encourage and keep afloat “troubled” institutions) to swap them with its own holdings of central government debt bills which they can then use either in private repo or even in targeted MLF at that particular monetary policy window.

It was, as I wrote, a two-for-one opportunity; banks could raise qualified capital via these bonds at the same time using them in repo for liquidity once swapped for central bank bills. Most people focused on the credit dimensions: the implicit need to increase bank capital. To me, it said a lot more about the repo possibilities, implying more immediate concerns.

China’s repo system appears to have been plagued already with some serious level of collateral insufficiency. Taking it one step further might’ve have pushed the tide out far enough to begin identifying the naked swimmers. And maybe not just in China.

OK, but anyone who’s still with me this far is going to ask how a UST collateral run, of sorts, gets into the Chinese RMB system in nearly the same way (or a China repo problem ending up in eurodollar futures). What’s the connection?

I think what brings all these seemingly unrelated things together is collateral transformation. The year 2017 was a Eurobond binge, one that was as much Chinese as Argentinian or Turkish. Some dealers, including some specific dealers, really bought into globally synchronized growth and what better way than in securities lending.

These would include those which extend in and out of China (maybe by way of Hong Kong, too, but that’s a different if related story). A Chinese bank which still needs dollars (each and every day of the year) could in 2017 (in theory) pledge lower quality China corporates to a eurodollar bank for UST’s in return so that the Chinese bank could then obtain dollar funding (either FX or direct in eurodollar repo).

We might even imagine the Chinese bank pledging lower quality RMB-denominated assets (for a little higher fee) in exchange for US$ denominated pristine collateral – with the eurodollar dealer taking on the exchange risk because in 2017 everything looked awesome!

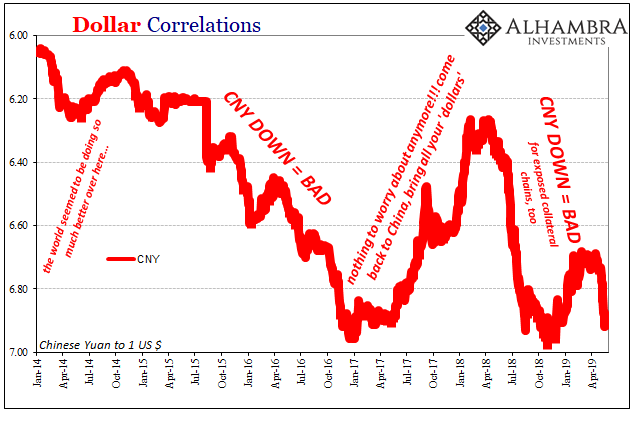

I don’t think it was an accident that CNY’s miraculous resurrection in 2017 was so far out of line.

Collateral chains both inside and outside of China would have been increasingly impaired once it started to fall apart in early 2018; especially after last April and then even more so during the world’s eurodollar landmine October to December. Thus, the timing of the PBOC’s perpetual bond/bill swap workaround as much in RMB repo.

The collateral signal goes both ways: as CNY fell backward again it reminded everyone the same liquidity risks, leaving the collateral chain inside and out susceptible to further and further impairment. A Chinese dealer who might’ve been using lower quality Chinese corporates for eurodollar securities lending is suddenly hit with a collateral call on them in US$ terms, which it then imports into RMB by enacting the same aversion down the line.

Inside China specifically, had Chinese dealers become too dependent on low-quality collateral for dollar as well as RMB funding? As they are hit with reversal in the one, they have no recourse in the other, either.

It’s the potential for a global collateral bottleneck, all linked together by this world-spanning eurodollar system which in its best days is just this flexible. Unfortunately, that’s also it’s downfall; the ability to take anything too far (and to take the word of central bankers that anyone should).

I wrote last week how in this way it’s not hard to see a little 2007 in recent events. Funding markets in RMB as eurodollars are all worried about something.

Then again, what would happen if the repo market hadn’t been there at all? Should collateral chains turn, no lender-of-last-resort. Even if it hasn’t yet, the very real idea that it could is a huge liquidity risk.

In China, it may already be more than just an idea. Beginning April 18, everyone inside the global system may have come to the same revelation.

Stay In Touch