Over the last decade, the US economy has been experiencing “residual seasonality.” It has begun each year unusually weak. For Economists expecting it take off in each and every one, this is more than a thorny contradiction. When it happened again in 2015, at the worst possible moment for the mainstream view, they had finally had enough.

The Bureau of Economic Analysis was called out for what was surely a quirk in their statistical processes. The BEA in response promised an exhaustive review, a comprehensive search to find this “residual seasonality” and then get rid of it from their data.

True to form, they didn’t find any evidence of statistical malfeasance but “fixed” their seasonal adjustments anyway. The squeaky wheel does get the revision.

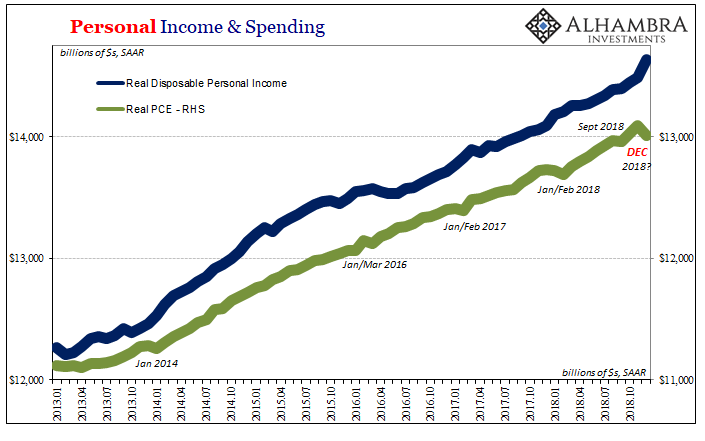

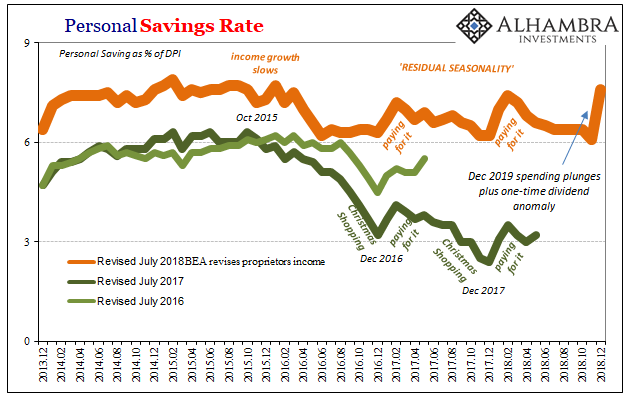

What really had happened was very simple. Income growth like the overall labor market never really recovered after the Great “Recession.” As such, Americans still like to splurge at Christmas as best they can only now they “pay” for their generosity by foregoing some spending the following January. At the margins, a statistically significant amount of activity is pulled forward a month.

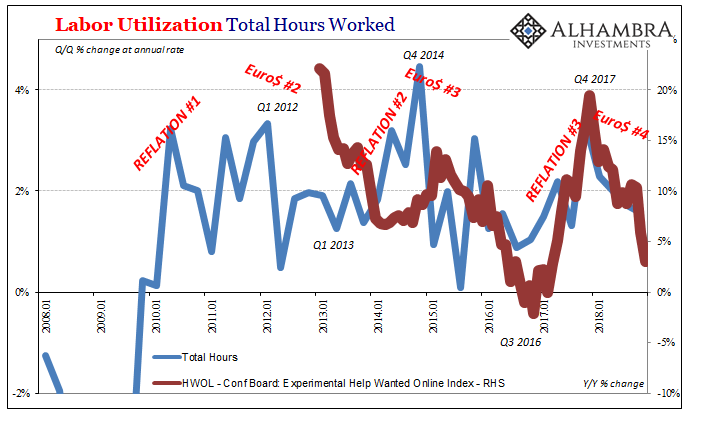

After 2014, though, this predictable seasonality became even more pronounced (thus, the revolt). The reason was equally simple; people began to perceive the opposite of what they were being told by Economists. The economy and the labor market were slowing not accelerating. Residual seasonality became even more residual; one month of holiday pulled forward several months from the following year.

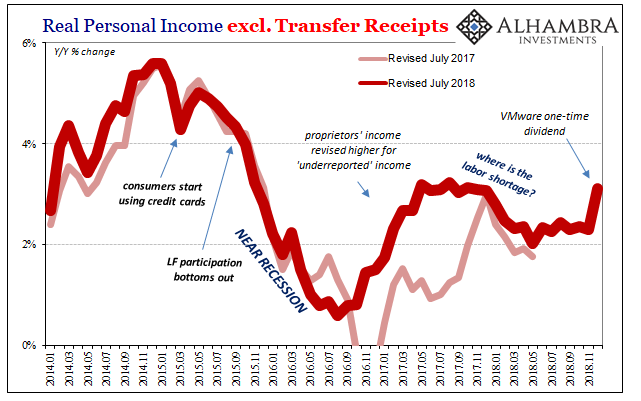

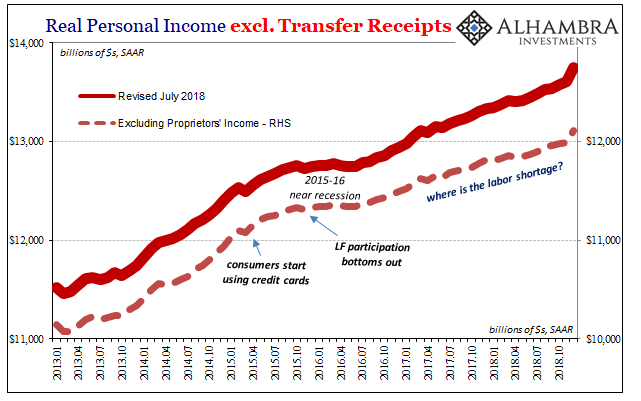

After many revisions, lo and behold current estimates for income growth do show what consumers were acting. Their caution and unease were very much reasonable; the income data very plainly illustrates an economy perched precariously close to a recession by late 2015.

It also shows there hasn’t been much if any recovery from that last downturn despite the passage of several years – and the constant, shrill shrieks of LABOR SHORTAGE!!! at every point along the way (until recently, that is).

Given this legitimate backdrop, we would expect the pattern to continue; Christmas up and then residual seasonality set to strike in January extending into February.

However, the Census Bureau presented us with an oddity last month when catching up on retail sales for the holiday zenith. They had plummeted far worse than we have come to expect even for the usual (for the last decade) downturn. It was reminiscent of Christmas 2007, not Christmas 2015.

Unusually weak retail sales were quickly dismissed in the mainstream, Larry Kudlow, the President’s chief economic advisor, calling it a “glitch” due to the government shutdown. Perhaps it was, but the Bureau of Economic Analysis in its PCE data today suggests that it wasn’t. There was a sharp drop in the broadest measure of consumer spending, too. The BEA and the Census Bureau both agree residual seasonality came early.

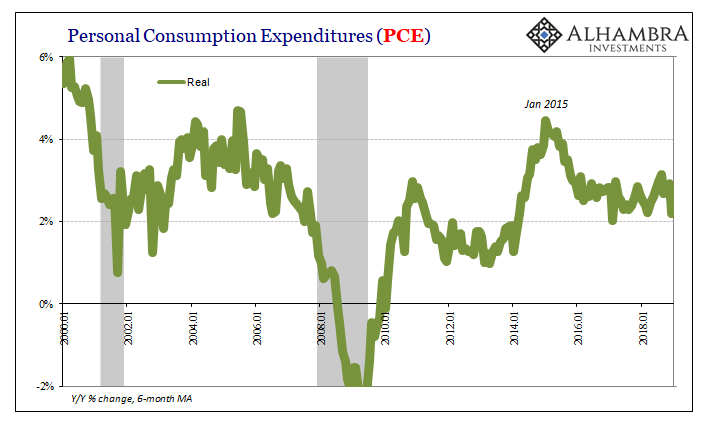

Consumer spending, for all the usage of the word “strong”, has been stuck in a rut. There is no booming economy nor importantly any hint of a tight labor market which would surely be indicated by the PCE data. That’s a crucial point given that US economic strength is perhaps the world’s best hope (according to the glitch people) for avoiding a full-scale downturn.

And if something unusually negative happened in December, then what’s the chances of a quick turnaround early this year? Much less than Larry Kudlow would like.

On the income side, the data was boosted by a one-time dividend payment from the private company VMware. On December 28, it paid a one-time special dividend of $26.81 per share. This worked out to about $11 billion in total, an amount sufficient especially as a one-off to easily distort aggregate income figures.

VMware’s dividend plus others increased Personal Dividend Income by $83.4 billion in December (annual rate), which has already been unwound by a $77.7 billion decrease in January 2019 (the data for Personal Income was updated today for both December and January; real figures are only for December since the BEA hasn’t yet caught up the PCE Deflator to that month).

The combination, though, of falling consumer spending plus the anomaly in income meant a sharp spike in the Personal Savings Rate.

At 7.6% in December, it was the highest since 2016 (though not really).

We are left with three takeaways. First, there continues to be not a single piece of evidence, income or spending, for a LABOR SHORTAGE!!! It just isn’t there. This is a fact that officials are forced to admit on occasion before they try to distract the public with the unemployment rate and what this other measure is supposed to mean for the future (but still hasn’t after now four years of this).

Second, the idea of US decoupling took a big hit when the BEA’s spending figures backed up the Census Bureau’s shocking numbers on retail sales. That would leave for anyone only the hope that what more and more seems like a worldwide rough patch is little more than a transitory one. Maybe things got dicey from October to December, but then picked back up if not in January then perhaps February (despite overseas indications not looking very good in those months so far).

Third, December 2018 really was striking in several key respects. Starting with residual seasonality, why would consumers give up on Christmas? It would take something new for them to do that. Market turmoil is certainly one aspect, but we also have to consider broader economic perceptions. As noted earlier this week, there is compelling data for the labor market in particular which had suggested weakening throughout last year.

Put that together with a bear market in stocks, and it could explain how Christmas ends up being conspicuously lean.

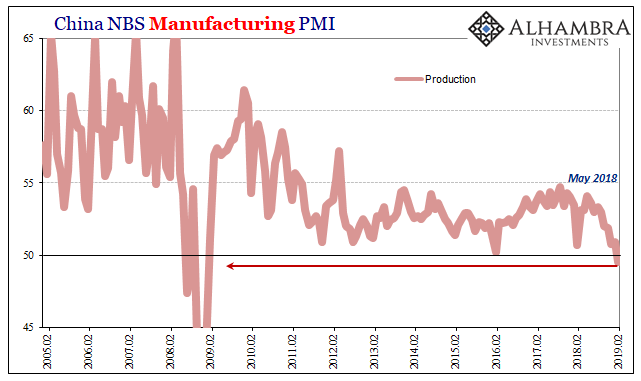

As such, there are further considerations, second and third order effects. Inventory, baseline settings, financial factors, etc. A shock of this magnitude isn’t likely to be an isolated one. If we’re astounded by the break in pattern, and we expect residual seasonality and weakness, what must it have been like for businesses up and down the global supply chain counting on Jay Powell’s forecasting?

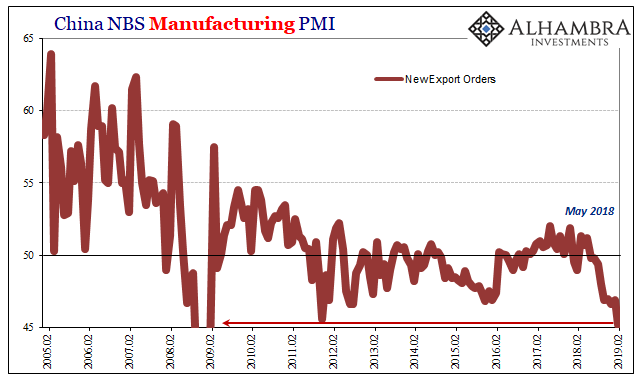

Considering that, perhaps it isn’t trade wars that are showing up in China’s recent PMI’s. The unusually low levels of orders, for January and February, no less, would now seem pretty consistent with unusual levels of American frugality.

Stay In Touch