Early last month, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported that the unemployment rate in the United States had fallen to just 3.6%. It was the lowest in half a century, seemingly an amazing feat for the most puzzling boom ever conceived. Everyone says it is going gangbusters, but is everyone saying so simply because everyone says so?

This one statistic is the key piece of evidence for something more tangible. The problem is that it is not unassailable. There are flaws in its design, potential inconsistencies never before faced. Even those who are willing to take it at face value still have to concede there’s something just not right about it.

In the Washington Post, one article published at the release of May’s payroll report said 3.6% was “…undeniably good — no, great — news that’s been a long time coming.” However, if you then add a serious caveat, is it really “undeniably good?”

But while things look as good as ever on the surface of the economy, there are a few potential problems lurking below. Which, when you think about it, is a pretty remarkable thing to be saying at this point of the business cycle. That’s because a lot of economists thought that the recovery would start to slow down on its own once unemployment got down to 4 or 5 percent, simply because there wouldn’t be enough new workers to keep it growing as fast — and that trying to keep it going beyond that would only turn into inflation.

Very simple and intuitive stuff. A 5% unemployment rate which the BLS figured as long ago as 2015 started to raise the probability of a labor shortage. Competition for scarce spare workers meant rising wages which companies then passed along to consumers in the form of higher prices, or inflation.

That’s what everyone has been screaming about the past few years, this LABOR SHORTAGE!!! Only, there’s no corroborating evidence for it. How can that be after so many years going lower and lower? You start to get the sense of something bigger than a single number.

If the labor shortage didn’t happen, then what about everything else?

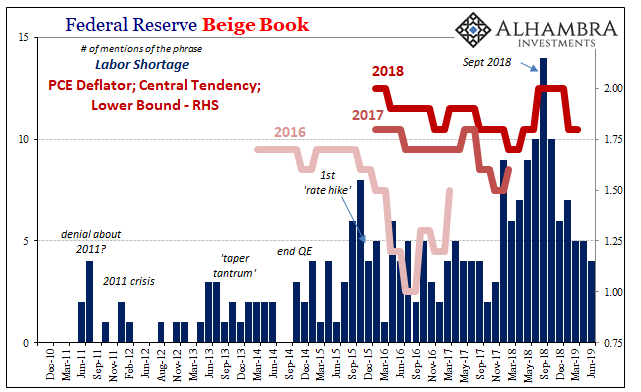

Even the most optimistic group of optimists isn’t talking about the thing much any longer. How can that be? The unemployment rate is the lowest in fifty years, but over the last eight or nine months the anecdotes compiled in the Fed’s Beige Book contain far, far fewer stories about a tight labor market.

In the May 2019 version, just released this week, there were only four instances of the phrase “labor shortage” (or “labor shortages”). There were fourteen of them in the September 2018 issue, quite a change and quite the interesting timing for that change.

The purported labor shortage disappears from the official landscape more and more as markets are gripped by inversions, tumult, and the closer predictions for rate cuts. It’s as if subconsciously these same monetary officials began to realize just how little the unemployment rate actually means – as the global economy seems to have struck a landmine just after the September collection of anecdotes.

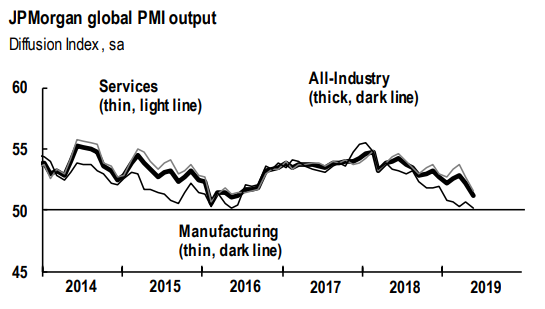

Though it is often wielded in the mainstream as some sort of shield from bond market inversions and pessimism, the unemployment rate is proving more and more ineffective as a defense. IHS Markit yesterday reported how JP Morgan’s Global Composite PMI fell to its lowest level in three years. And it was labor market strength which was supposed to have led to US decoupling:

The slowdown was mainly centred [sic] on the US, where weaker increases in the manufacturing and service sector led to the slowest rise in all-industry activity for three years. Rates of overall expansion also slowed in China (three-month low), Japan and Russia (36-month low).

Note the timing shown above. This isn’t a slowdown which started yesterday. It has been in the works for more than a year already – a year plus in which the unemployment rate has fallen further and further.

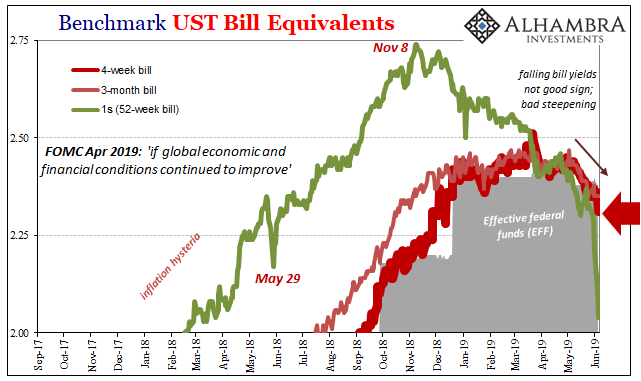

And during that time, the official line has moved from unequivocally strong economy and rate hikes to transitory soft patch and no more rate hikes to now rate cuts as insurance to keep the boom going. In other words, based on this same unemployment rate, Jay Powell says rate cuts would be a kind of prophylactic measure of safety for an otherwise healthy body.

The bond market, which has been proved right, even from the very beginnings of globally synchronized growth, is saying there is no labor shortage and there never was. What that means is a series of rate cuts from panicked Fed members who are going to end up realizing they have this all wrong.

Powell and his group already sense that they might, which is why the labor shortage has almost entirely vanished from the official accounts; the Beige Book being one of them. The inverted curves, especially now plummeting bill yields, these say to Powell you don’t yet know just how wrong you were to have depended upon that one suspect number.

You are about to find out, though. Maybe as soon as tomorrow’s payroll report?

Stay In Touch