Even I’ve become numb over the years to some of the blatant mischaracterizations. Looking at any small positive number for whatever small economic account and declaring it the mark of a strong economy is standard procedure nowadays. But it’s the brazenness with which “they” are now attempting to discount the sudden reappearance of the minuses.

I’ve said all along that Economists had staked everything on 2017 and globally synchronized growth. Inflation hysteria was emotion not analysis. It had to be true… because.

Finding out in 2018 that it really wasn’t is a discredit too far. Economics may never recover, so we’ve been treated to the outright transformation into propaganda. At least with globally synchronized growth it was technically true, the deviousness being in framing how this was to be interpreted.

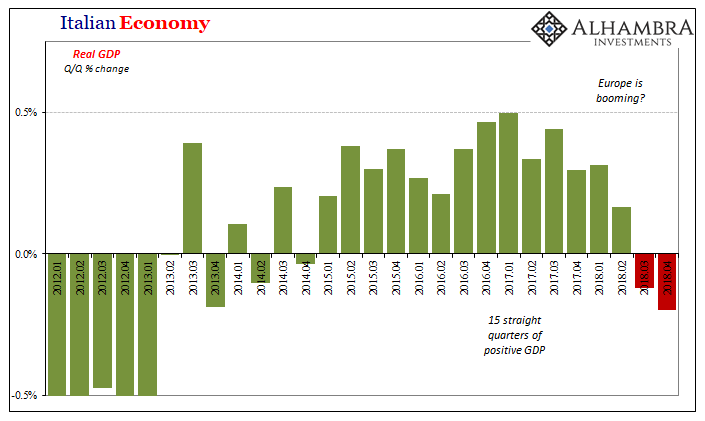

As expected, Italy’s economy shrank for a second straight quarter according to estimates released today. Since it wasn’t supposed to go this way, people are confused and some are asking how and why. The Economist (of course it’s the Economist) just outright lies about them.

Italy’s recession is partly home-grown. In September 2018 its populist government unveiled budget plans for 2019 that defied the European Union’s fiscal rules. As the row with Brussels worsened, government borrowing costs rose sharply.

Notice there is nothing about Q3’s contraction, which started this “technical” recession before there ever was a populist budget to blame. The real kicker is how this political “row with Brussels” is supposed to have brought down the economy:

A survey of lenders by the European Central Bank found that in the fourth quarter of 2018 Italian banks became more fussy about whom they lent to, even as credit standards in other large euro-zone countries eased.

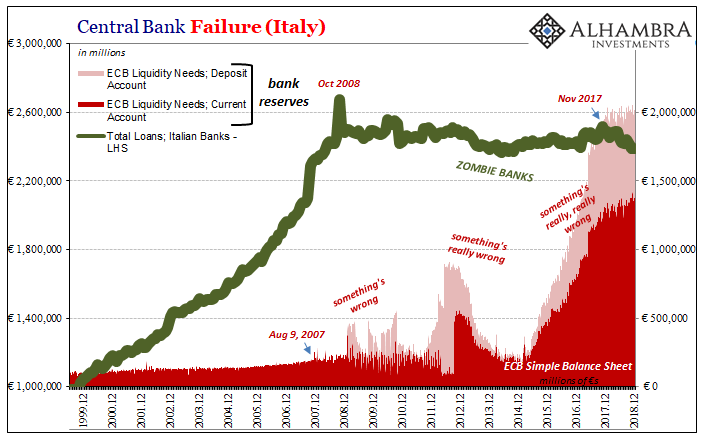

Sounds somewhat plausible; higher interest rates on the Italian risk-free, perceptions of risk, banks cutting back lending. And that’s just what has happened. Only, it started long before the populist budget.

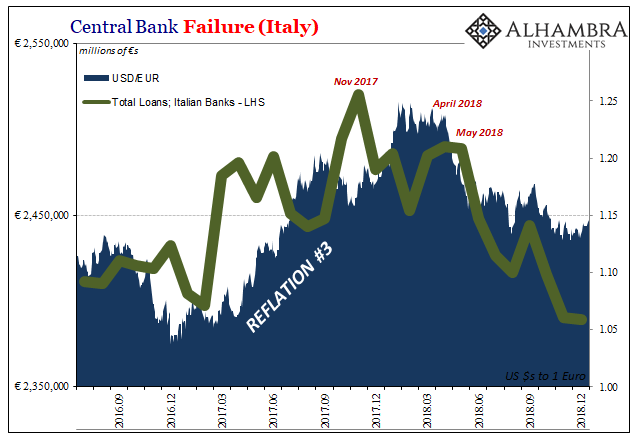

Italian banks have been “more fussy” since November 2017. Bank lending had been scaled back in Italy for almost a year before the Italian political business and rising sovereign yields.

This would actually explain Q3’s contraction as well as Q4’s, in addition to why Italy’s economy like Germany’s or the rest of Europe’s seemed to have hit a wall in 2018 contrary to every single forecast and proclamation.

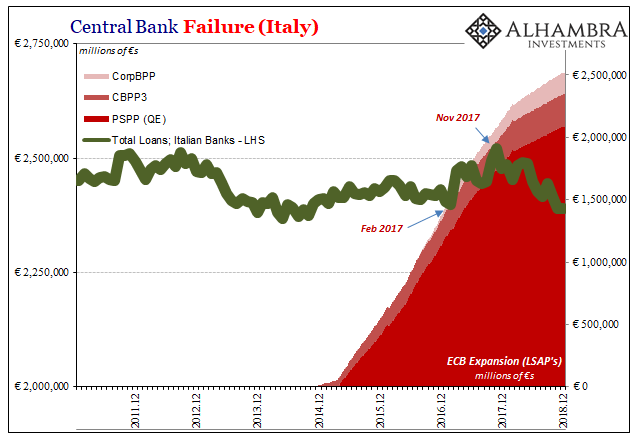

Everyone just uses the shorthand. QE is quantitative easing because why? Central bankers say it is.

They’ve said all along that the banking system is the key to recovery. That part, they got right. To achieve this, we were all told a flood of liquidity was required. So much, banks would stop worrying about all that 2008-style liquidity stuff and get back to the business of being banks.

You can tell by the fact that Italian as other European and American banks haven’t done that something is already very wrong long before we start with 2017 and 2018.

The ECB as other central banks developed a number of schemes to achieve the desired liquidity, all enlarging the stock of bank reserves. If QE is E it is by this one property. But are bank reserves liquidity?

That’s the question nobody ever asks because the answer staring back at everyone is a resounding NO.

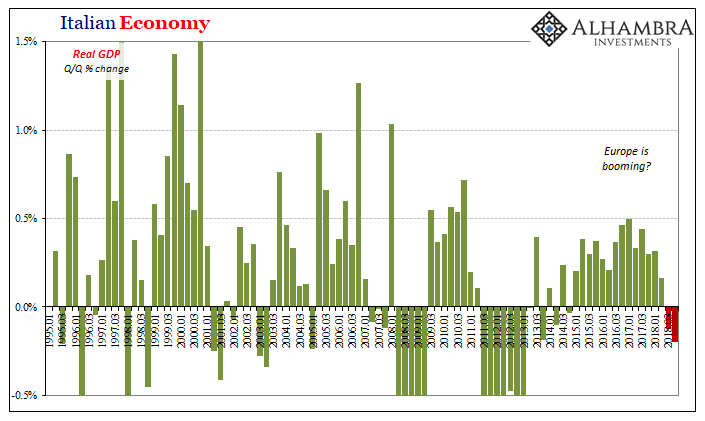

Look at Italian banks. Lending rose if briefly in 2017, up by about 4% which is nothing like a booming bank book. Still, lending was up, but was it because of QE and the rest of the ECB’s LSAP’s (the major three pictured above)?

That specific time period was worldwide Reflation #3, the very same months when the euro rose sharply, meaning the dollar fell. Globally synchronized growth so long as financial and monetary conditions were favorable. What changed around December 2017?

Financial and monetary conditions especially as they related to the global monetary reserve, this credit-based currency system. The euro sank, meaning liquidity risks rose (again) and not just risks, either. Since bank reserves truly play no role in banking decisions, Italian banks were, like their global eurodollar compatriots, already cutting back all the while Mario Draghi or Jay Powell were reassuring the public just how awesome the boom was – and how it was right then about to become even better (thus, rate hikes and QE exits).

You know who was heavy into selling that message?

The above was the Economist’s cover from one weekly edition in February 2018. Somehow, with Jay Powell now having abandoned the unemployment rate and the ECB likewise on indefinite hold, I doubt a similar cover will be painted up for February 2019. They’ll keep saying that Italy’s problems are Italy’s alone, until Germany then Europe then Japan then China then even Trump’s USA are all drawn into a single global downturn.

This is a worldwide problem. Everyone says it, even Italy’s Prime Minister yesterday acknowledged, “The good news is that it doesn’t depend on us, when the US and China will find an agreement, we will immediately start.” In other words, global growth abandoned them. Giuseppe Conte just hasn’t found the ECB’s stats on Italian bank lending yet.

But he is right about that one thing even if he hasn’t been shown why. I wrote just yesterday:

What happened in 2017 was simply the overhyping of the positive numbers particularly under the framework of “global growth”, synchronized in this updated case. Europe’s internal economy was supported by that rather than QE. Thus, as “global growth” curiously disappears, so too does Europe’s.

And so too does European liquidity. Bank reserves remain, but the presumed effect just disappeared. It wasn’t the US and China that struck the global economy in December 2017 and January 2018.

Everyone stretched the truth about recovery in Italy and everywhere else, Economists most of all. They had to in 2017, their last chance to get it right. This is beyond straddling the line, though, between plausible and plain ridiculous. It’s bigger than lying about Italy’s banking, much bigger than populist budgets and country-specific factors.

The problem isn’t the prospect for a global downturn, it is the rising probability of another downturn without having ever recovered from the previous ones. Some people just might start asking the right questions. Economists won’t answer them at least not directly because they can’t.

Stay In Touch