There were only two possibilities and both related to their release. Either the Communist Chinese government was going to delay them, or would just say, screw it, everyone knows they’re going to be bad so let ‘em fly. There weren’t any questions about the data itself.

Sure enough, the first glimpse at China’s economy in its full virus effects was one beyond ugly. Both the manufacturing and non-manufacturing indices plummeted. And the word “plummeted” is understated here. In fact, they went well below where even the direst forecast had prefigured.

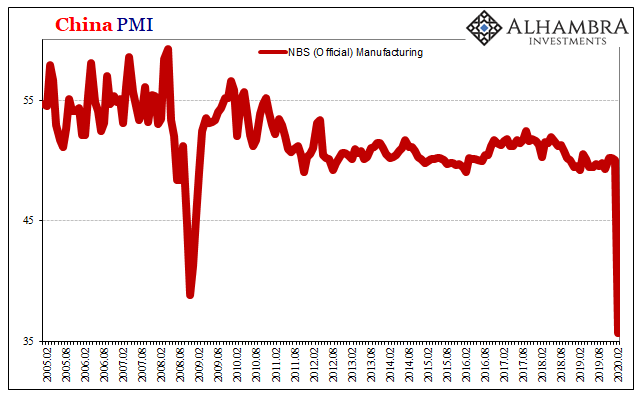

China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reported late Friday that its manufacturing PMI was 35.7 for February 2020. It had been 50 in January and already sliding backward. Most Economists, those who had been surveyed, were thinking it might drop as low as 45 given how the government’s efforts to fight the coronavirus outbreak would take their economic toll.

The lowest the index had ever achieved during the Global Financial Crisis was 38.8 for November 2008.

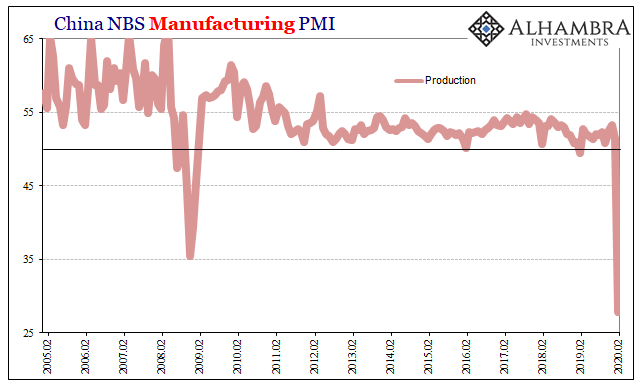

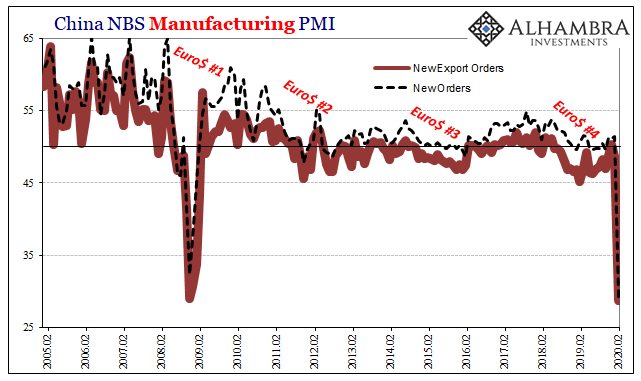

All the internals ended up situated the same. The Production index crashed to 27.8 in February from 51.3. New Orders collapsed to 29.3 while New Export Orders fell to 28.7 (from 48.7 in January). So much for strength from the rest of the world.

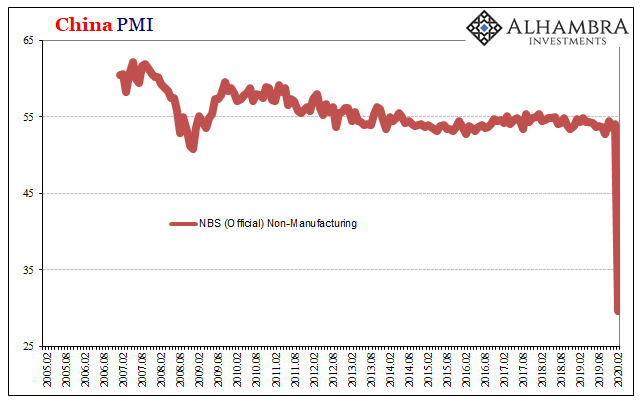

Somehow it was even worse for China’s services sector. The NBS Non-Manufacturing PMI actually came in under 30, below the always-trailing manufacturing, services falling all the way to 29.6. This index had been surprisingly higher in January at 54.1.

As with its manufacturing cousin, the internals of the service sector look just as nasty. New Orders went from 50.6 (already low) to 26.5 (off the charts). Even the Business Expectations component index dropped substantially, coming in at just 40.0 in February following a 59.6 in January (the expectations index is almost always near 60).

Unlike the Chinese manufacturing experience during the Great “Recession”, China’s service economy, at least according to the government’s purchasing managers survey, never came close to something like this. The non-manufacturing PMI had never been below 50 before, the worst having been 50.8 in December 2008.

Given these startling estimates, substantially below all the lowest of low expectations as well as previous history, I was interested in how China’s economic authorities would characterize them. It doesn’t matter how bad the economic numbers may be, whether record low industrial production estimates or the slow squeeze of GDP, like any authoritarian regime they are always declared to be the expected great work of awesome, smartly crafted and expertly designed policies no matter what the calculations might be.

Friday’s press release began with a small dose of abnormal sobriety…

Affected by novel coronavirus pneumonia in February 2020, the Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) of China has dropped significantly.

…before it quickly returned to type.

But with the overall promotion of epidemic prevention and control and economic and social development by the CPC Central Committee and State Council, the recovery rate of enterprises was picking up rapidly, and production and operation activities were recovering in an orderly manner.

It’s easy to criticize the Communists for this sort of obvious spin, but this is a template that is already being used in the West, too. The reason the Chinese government could start out so truthfully was the same reason Jay Powell will be induced to his next series of rate cuts. People won’t remember the cause so much as the response to it.

For Powell, as the Communists, he can claim that whatever happens from here wasn’t his fault. Just like all the prior Chinese press releases optimistically talking up the increasingly dismal results the past few years, for the Federal Reserve the story will also be an awesome economy, thanks to Powell’s courage and steadfast approach, that was derailed by an outbreak of physical disease rather than the monetary type that had been evident for years already.

While the Fed still hasn’t offered any response, yet, the markets are all certain one is forthcoming.

The PBOC, by contrast, had already delivered at least the first round of its counteractions – though the details of it had been delayed (without any reason given) for two weeks. The central bank finally posted the results of its balance sheet for the month of January 2020, the first month under the obvious strain of the outbreak.

As you would expect, there had been a clear and concerted effort to ensure liquidity (keep in mind, too, that January was China’s New Year). But it wasn’t anything like what you might have been thinking given the implications of this February PMI data.

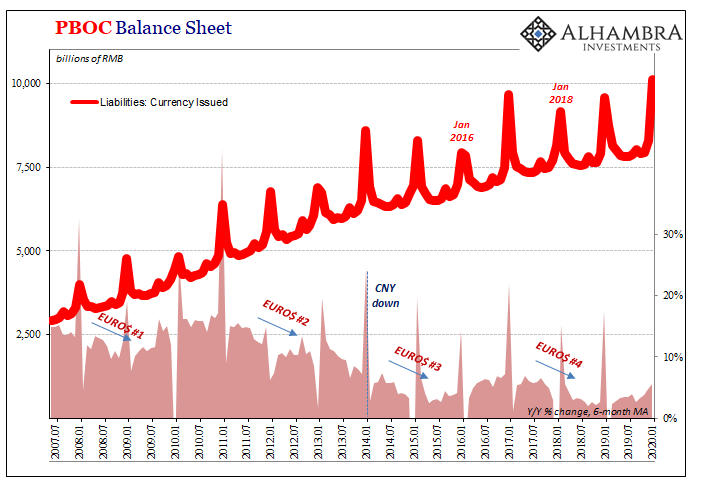

For example, for a Golden Week January the level of currency float was increased by more than the PBOC had allowed in years. When you put it that way it does sound consistent with a precarious economic situation. But the growth rate was just 5.6% in January 2020, and while true that was the highest rate in years it was only equivalent to a month like March 2018; hardly close to anyone’s idea of a massive policy change.

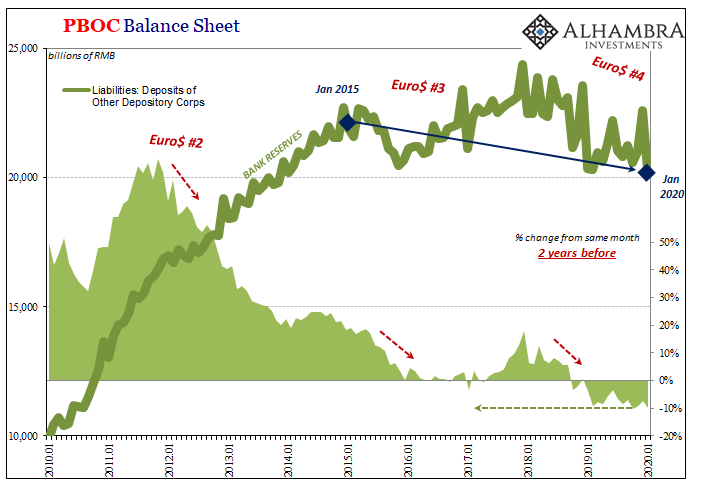

And while the level of bank reserves (Deposits of Other Depository Corporations) was almost flat year-over-year two months ago, -0.4%, it was still 10% less than it had been the two Januaries before (2018).

In other words, while the PMI data suggests perhaps a massive plunge in the economy, the PBOC balance sheet numbers confirm a more modest, even measured approach.

Maybe the latter was altered, central bankers turning panicky during February as the situation deteriorated. The other possibility is the PMI figures are overstating things; the very limited nature of sentiment surveys. What these try to tell us is how many businesses being surveyed are reporting lower levels of activity; they don’t say by how much for each one.

It is merely assumed that when a whole lot fewer manufacturers or service providers are reporting temporal decreases when compared to the month or year before that such an outcome is consistent with an overall contraction. But these PMI numbers are obvious outliers – there is no frame of reference by which to analyze them. And you never, ever go by a single monthly estimate.

It is possible that the government’s press release is closer to the real situation (I wrote “closer”, not “close”) than we might want to give them credit for. The PMI data is suggesting a real outlier event, and at this point maybe even a temporary one.

And to a certain extent it doesn’t really matter. What we are all interested in is, apart from the human costs, the economic fallout from it. Does it continue? Does it spread like the disease? Can it be contained?

That’s where it gets far more complicated – especially considering how the global economy was already in bad shape when the outbreak began. China most of all. And given how PMI’s work, how they are put together, it wouldn’t be at all surprising if for March 2020 they absolute surge from where they are now. A possible 40 or 45 will never have looked so good.

But that probably won’t mean what the February changes seem to indicate, either. We won’t know the actual state of affairs until after the initial shock gets sorted out and processed by Adam Smith’s invisible hand. Even in China. All that the PMI data tells us is that there was one, the coronavirus was indeed a substantial shock.

Stay In Touch