Last month, a group of central bank governors from across the South Pacific region gathered in Australia to move forward the idea of a KYC utility. If you haven’t heard of KYC, or know your customer, it is a growing legal requirement that is being, and has been, imposed on banks all over the world. Spurred by anti-money laundering efforts undertaken first by the European Union, more and more governments are forcing global banks to take part.

KYC is a particularly onerous demand. Essentially a compliance function, the costs are high given the huge administrative difficulties that often amount to repetitive manual tasks in the back office. Tracking customer accounts from all over the world is easier said than done.

Making that information transmittable from one depository to the next is a nightmare.

As a result, private groups and joint ventures have been formed along with public-private partnerships, including potentially using blockchain technology. The idea is to make the chore less of one and therefore significantly less burdensome for the banking system.

And there is a fair amount of urgency to it. Not because of some worldwide crime spree which has led to an outbreak of suspected money laundering. Rather, officials all across the globe are growing worried about another perhaps related drawback far greater than criminal activity.

You probably haven’t heard anything about it, either, but the world has a correspondent banking problem on its hands.

What is correspondent banking? It is, essentially, an ad hoc network of various financial institutions who link themselves together out of necessity so as to more efficiently handle global monetary flows. You may have been led to believe that there is a SWIFT system and that’s the extent of the world’s payments infrastructure; not even close.

As always when dealing with any global monetary requirement, there has to be a deep and good-functioning foundation and substructure to handle and fluidly process the dizzying array of payments demands. A global currency system regardless of denomination is an intensive affair. In a globalized economy, moving funds around from one place to the next is essential.

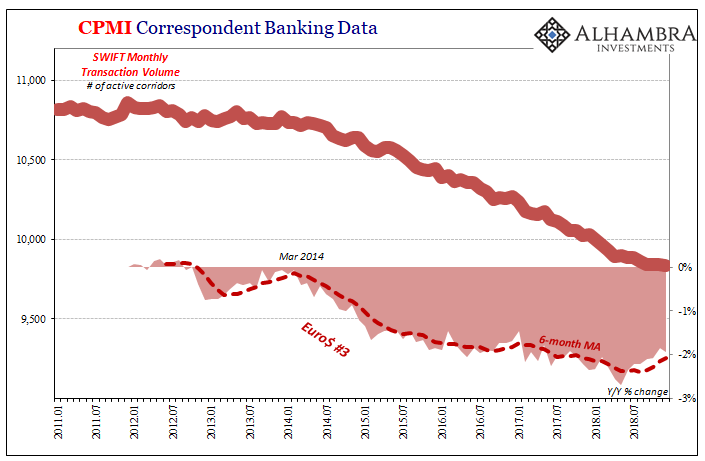

The number of banks around the world participating in these correspondent networks, called corridors, however, has been shrinking since around 2011 with the pace of withdrawal picking up substantially during and after…2014.

Authorities have been largely baffled by this. No one, of course, saw it coming. When the decline accelerated into 2015, some supranational organizations decided it was time to maybe figure out what was going on throughout the banking scene. In November of that year, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) issued a lengthy report to the G20 nations.

It identified several reasons banks had given for their growing reluctance to take part here. Among them was regulations, including the costly anti-money laundering provisions that institutions were less than thrilled about tackling. To start tracking customers from bank to bank (called “open banking”) was a potential landmine on top of a nuclear detonator.

Thus, the urgency in Australia. Of all the factors the FSB had cited for the ill-health of correspondent networks, KYC was one that authorities could at least offer some direction and direct aid. Creating something like a utility such that it would theoretically offset some of those costs, so it has been hoped this will bring some institutions back into the correspondent business. Authorities don’t really know what else to do.

More wishful thinking than anything, these kinds of regulations have been more nuisances rather than full-blown roadblocks. What the banks had really said, what they found most unappealing, was that they couldn’t make any money in global money. From the FSB report:

As regards the causes of the phenomenon, authorities and local banks that responded to the World Bank point predominantly to risk appetite/profitability as the main drivers. Some noted that, after the crisis banks have tended to reassess the profitability of their business lines, customers and customer jurisdictions, partly in response to higher capital and liquidity requirements which are now increasingly charged to local business lines. [emphasis added]

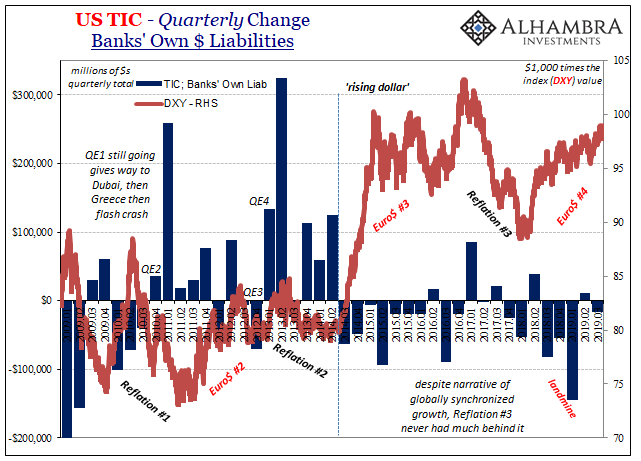

Even here the FSB can’t help but cite regulations when the whole point about capital and liquidity as they relate to profitability is far, far deeper than the LCR or SLR impositions. If the opportunity existed to make money in these functions as banks once did in the pre-crisis era, they’d be falling all over themselves to hire (another) army of lawyers and lobbyists to chip away at those regulations.

Instead, they’ve decided it’s just not worth the effort. Global money is just not worth the tremendous potential risks that global banks were made all-too-aware of when Bear Stearns went under (or nearly so) for the given perceptions about any upside. Starting with liquidity risks that no QE has been able to address.

Regulatory costs like KYC or banking directives simply cut a little more into an already unfavorable profit calculation.

If banks can’t make money in this offshore, global space, they aren’t going to create the necessary “currency” to keep it functioning and as a further consequence there’s less motivation to participation in the redistribution and movement of said monetary resources.

The Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI), located in Basel, Switzerland, is tasked with monitoring the health and cooperation of the global payments infrastructure. Working closely with the BIS and SWIFT, CPMI has been keeping track of these correspondent corridors using SWIFT data.

How big of a problem has this become?

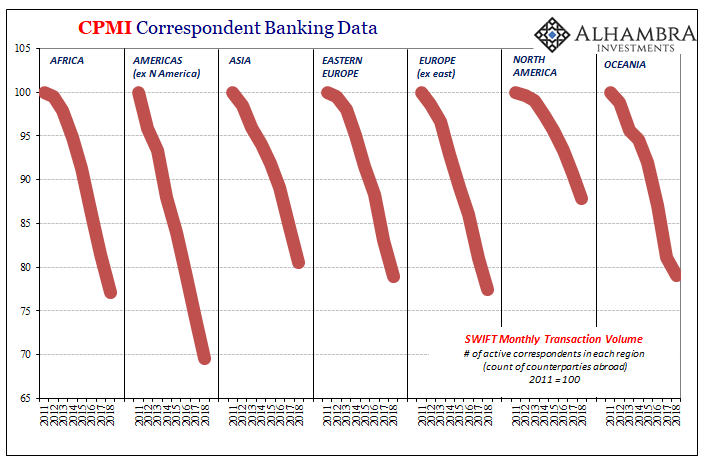

According to the CPMI, the number of corridors (again, private multi-institution networks of correspondent banks) has declined from around 10,800 per month at the peak in 2011, when records were first kept, to about 9,800 in December 2018 (the latest figures). As you can see above, 2014 seems to have been interesting point of demarcation for both money creation as well as payments processing.

The number of correspondents operating within those corridors has shrunk even more dramatically. From a peak of about 128,000 per month back in December 2011, the committee thinks there was less than 104,000 in December 2018, a decline near 20%.

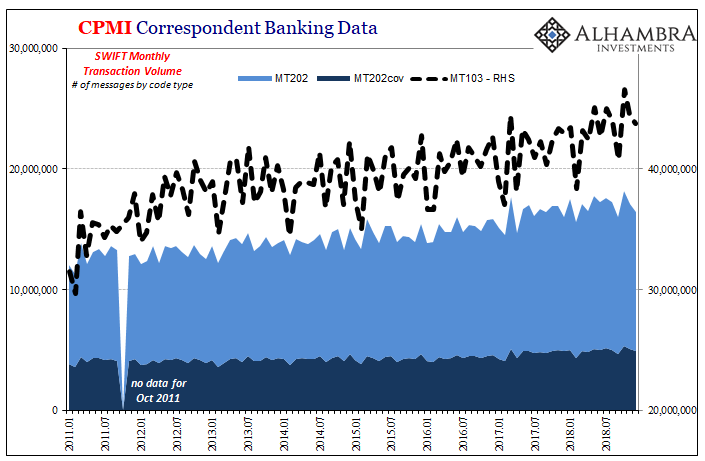

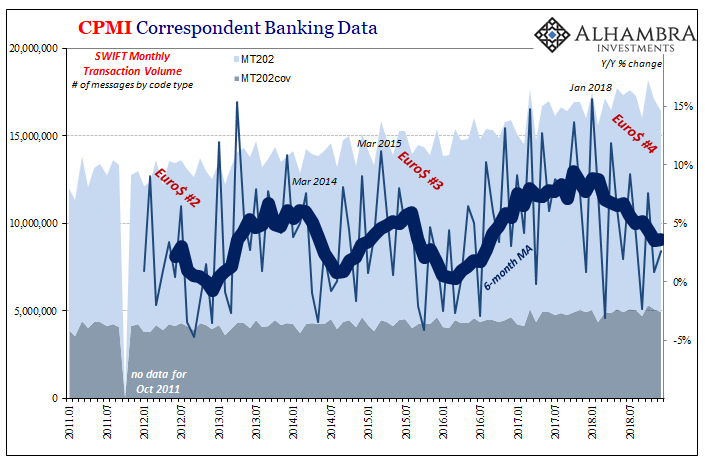

The number of SWIFT messages (NOTE: MT103 codes are those relating to single customer transfers, while MT202’s are interbank messages between general financial institutions) being sent within these corridors has risen, as you would expect, but the fewer number of correspondents means that more and more these payment requests are being concentrated on fewer and fewer participants.

The FSB noted in 2015 how these remaining firms tended to be of the small and mid-sized regional banks rather than the large global behemoths that once roamed freely and uninhibited across all facets of this offshore monetary world.

As a result, the payment system is being de-dollarized which, contrary to what the cheerleaders for China argue, is a bad thing – because nothing is actually replacing the dollar. The once-fluid global system is fragmenting along regional lines.

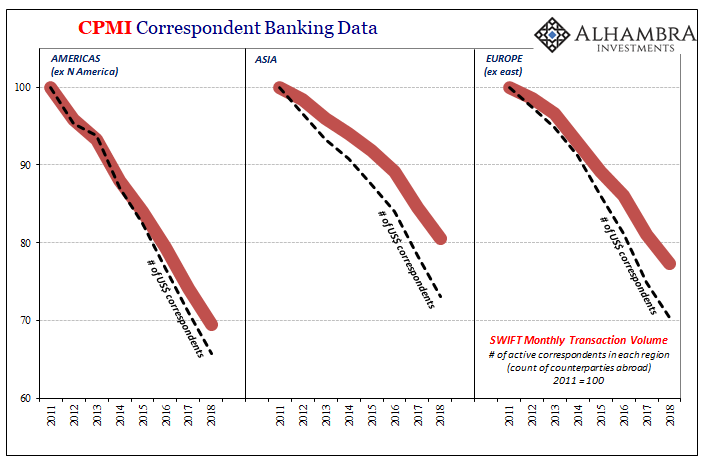

The problem is most visible in the Americas (excluding North America) as well as Africa and perhaps surprisingly Europe (not including Eastern Europe). Moreover, leading the way in retreat are those correspondents formerly active in processing US$ payments.

In Europe, for example, the raw number of active monthly correspondents has declined by about 23% total since 2011. The number of active monthly US$ correspondents is down by 30%.

In other words, the big guys had created the “dollars” (as well as other currencies) that the whole vast network(s) would transmit back and forth as needed in a globalizing economy. Since 2011, and really 2014, the bigger players have taken a step back in monetary creation (as we know from other sources like TIC) as well as payments processing.

Only a few have noticed the latter while, frustratingly, no one bothers about the former (something, something QE money printing).

Some authorities on the payments side have grown concerned about possible chokepoints arising from the dearth of willing correspondents without ever conceiving of how liquidity has played such a huge role in creating it (and the chokepoints). It has been assumed that the big issue is how no one wants to process all these “dollars” when, putting it altogether, we can see instead how it all begins with the formation of them.

If banks don’t want to carve out increasingly precious balance sheet space for offshore money origination, they sure aren’t going to want to go through the tedious and low profit business of processing the payments – making everything, like global trade, that much harder and inflexible. It is being left instead to the middle tiers of banks who might be more eager to process but lack the ability and scale to create what it is that is supposed to be processed.

Calling it de-dollarization is somewhat overdramatic. It’s not like there’s a rush from the dollar into anything else. Rather, because the dollar has been so dominant when the entire system retreats that’s what anyone will notice – assuming anyone notices. It is de-dollarizing by default. A decline in banking therefore dollars.

That’s because the big issue here isn’t the denomination; as if replacing the global reserve of eurodollars with euroeuros (or, totally implausibly, Hong Kong euroyuan) will make any difference. Remember, this is a credit-based system which means a depth of infrastructure and capacities that only banks provide. The less banks provide in any of these capacities, it won’t matter the denomination.

Without the banks, we know there’s less money (liquidity) and, not surprisingly as it turns out, fewer left to handle the other important demands of global money.

This is simply another view upon on implied capacities of that global monetary system consistent with others showing how monetary capabilities are, and remain, in serious decline. Another way of arriving at Milton Friedman’s interest rate fallacy for a global rather than simply national monetary system. The increasingly “missing” infrastructure behind the much more important private reserves you don’t ever hear about or factor as the Fed “somehow” seems trapped by repo.

Stay In Touch