One of the primary reasons Economists go unchallenged is because they’ve made the subject matter dense and complex. Needlessly so, in many cases. Anyone in the financial media or the public who wishes to challenge Jay Powell (well, maybe not Powell) on any economic concept is as likely to get a lecture on regressions and the three or four tests the Fed uses to seek out heteroscedasticity in its models, all of which purposefully avoids answering the question originally asked.

The more uncomfortable the question, the more dissembling the pseudo-scientific rant as reply. That’s the real fedspeak.

In August 2010, for example, then-Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke was confronted by another challenge he and his fellow policymakers never expected. They never anticipated the Great “Recession”, either, despite numerous market warnings as far back as 2006 that they simply shrugged off. Having just lived through the “somehow” Global Financial Crisis, they couldn’t afford to be so flippant in its aftermath.

In his speech delivered at Jackson Hole, the one that pre-announced a second round of QE, Bernanke began with an honest assessment of the situation. It wasn’t good – even though there had already been a QE1 and ZIRP. Quite naturally, people might have begun to wonder how effective the first one really had been if so soon after (QE1 terminated at the end of March 2010) there’s already a need for a second.

A first option for providing additional monetary accommodation, if necessary, is to expand the Federal Reserve’s holdings of longer-term securities. As I noted earlier, the evidence suggests that the Fed’s earlier program of purchases was effective in bringing down term premiums and lowering the costs of borrowing in a number of private credit markets.

Say what? Term premiums?

Nobody cares about term premiums and Fisherian deconstruction. What anyone wants to know is incredibly simple; whether or not QE actually works. Judging the effectiveness of monetary policy in reality is an end game scenario. Either there is a recovery, or there isn’t. And if there isn’t, it didn’t work.

So, Chairman Bernanke traveled to Wyoming as the nascent and already questionable recovery from the deepest and most sustained (and “somehow” global) economic contraction since the Great Depression was unexpectedly foundering. Officials had already skated by having avoided the uncomfortable questions as to how there was a Great “Recession” on their watch in the first place.

Thus was born policymakers’ longstanding and ongoing infatuation with term premiums. They don’t show up much at all in the mainstream literature before then (not with Alan Greenspan and his series of one-year forwards already confusing things). In the absence of robust recovery, or any sense of real recovery, how does any official justify the eventual four programs of QE?

Should anyone ask if QE was effective, Bernanke (and Yellen) would always answer with “term premiums.” Not recovery, accelerating growth, or robust inflation. Term premiums!

Why?

Because these are just complicated enough so that no one really understands what anyone referring to them might be talking about. And since they aren’t observable, term premiums are simulated using complex mathematical models, the questioner is immediately at a huge disadvantage. The perfect getaway setup.

But it really shouldn’t be this way. Like any good high school math teacher, demand that these people show their work. Don’t ever allow them to just produce an answer without first producing the calculations backing it up. And I don’t mean the regressions.

The thing about term premiums is really two things; first, forgetting the fact that they are a ridiculous made up idea so that Economists can try (and fail) to plug interest rates into econometric models (in the few cases they do), simulations already suggest term premiums have fallen more without QE than with it. Even on its own terms, term premiums fail to live up.

Bernanke in 2015 conceded that point:

What about the decline in longer-term yields since early 2014? In the US at least, that decline is somewhat surprising, as economic fundamentals have recently seemed more consistent with rising, not falling, longer-term yields… By the process of elimination, with fundamentals stable or improving, much of the decline in yields over the past year must reflect a sharp drop in term premiums. [emphasis added]

What did he eliminate in his thought process in order to blame solely term premiums? The other two parts of nominal yields – both of which, unfortunately for Dr. Bernanke, we do have observable inputs for. There are markets which do give us a very good, and robust, sense of the other factors being considered in falling yields.

Those other two pieces are inflation expectations and the anticipated future path of short-term interest rates. (I’ve written about term premiums and rate decomposition here if you want more details and descriptions.) They are Bernanke’s second downfall.

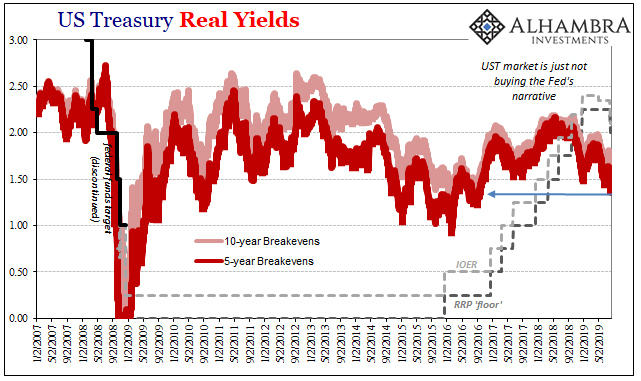

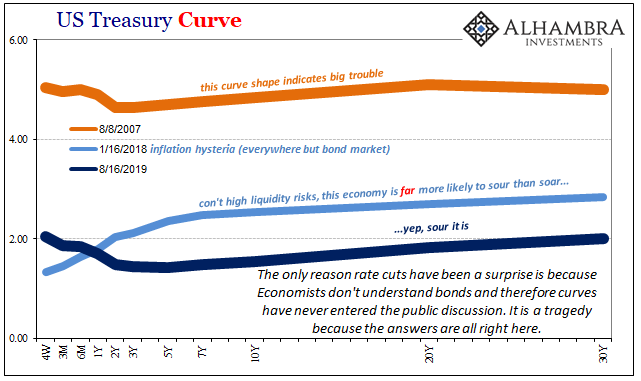

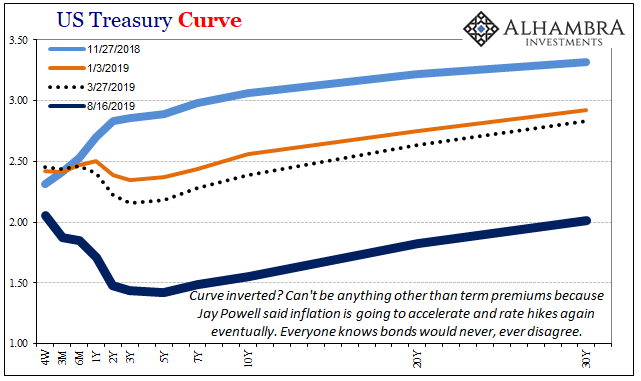

The reason it has to be term premiums is because Bernanke, Janet Yellen, or Jay Powell all say inflation is going to rise and so will short-term interest rates. Guaranteed. Take it to the bank. The Fed will therefore be hiking short-term rates and since they don’t believe the bond market would ever, ever disagree with them, process of elimination, it therefore must be term premiums that are causing yields to fall (when these same people say they should be rising).

Whether in 2015 or more recently, the market evidence for the other two pieces of the yield picture are pretty unequivocal. The market is obviously expecting a very different set of circumstances than policymakers, an increasingly dangerous scenario of lower inflation, not higher, at the same time it is thinking lower short-term rates, not rate hikes.

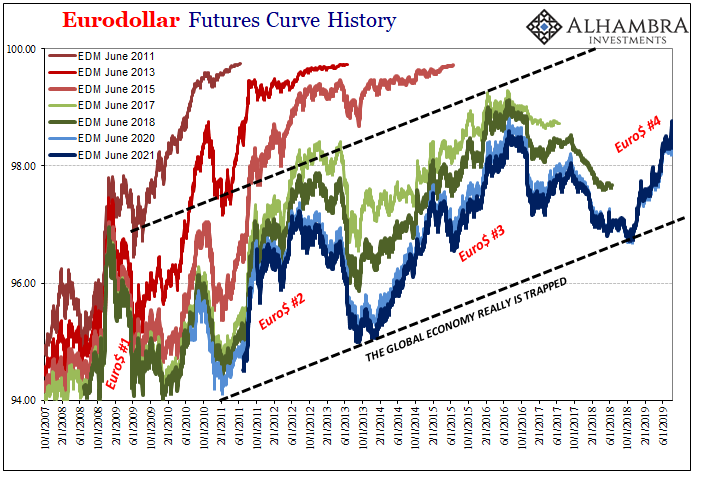

Not for nothing, the eurodollar futures curve inverted all the way back in June 2018 at a time when everyone thought the very idea of rate cuts was absurd. With one rate cut now in the books, the market-based inputs are showing their work.

It actually isn’t all that difficult to challenge the assertion, especially with market prices in hand. And it’s becoming even more of a necessity now that people are (finally) paying attention to the yield curve.

This week Janet Yellen started the clown show by saying you shouldn’t trust the inversion. Why not? Term premiums. She wasn’t the only one; it spread immediately around the world. Yesterday:

I’m not sure I would be relying on the yield curve as the best signal of that risk given the yield curve has obviously not got the same sort of structure that it’s had historically.

That was the typically unchallenged judgment of one deputy governor from the Reserve Bank of Australia. With nominal rates collapsing in the US and elsewhere, not only must term premiums be low they must now be really, really negative. That’s the only way left to (try to) dismiss what is, and has been for awhile, otherwise a very obvious negative signal.

They get away with what is pretty clear nonsense (deeply negative term premiums fail every measure of logic) because they know they’ll never, ever be asked to show their work.

Not only has the market already done it, unlike Yellen’s and Bernanke’s its proofs are being tested and validated as we speak. As I wrote elsewhere:

The inverted curve is simply the market saying to Janet Yellen, I told you so but like 2007 you refused to listen…

That’s the problem with being forced into looking at everything backward. No matter how much you try to convince yourself that R-stars and term premiums are meaningful and righteous assessments, you can’t ever shake that nagging feeling that the thing really is what it is.

Term premiums are not science nor really math. They are made up and more than that they are rationalizations, truly Orwellian, intended to deny the obvious and straightforward signals coming from the very fundamental building blocks of all finance and economy. The entire notion is purposefully shrouded in unnecessarily complex concepts whose only true use is to attempt to answer for the otherwise inexcusable.

As I often write, Economists don’t understand bonds. But they know just enough of them to understand that they had better change the subject.

Stay In Touch