It is the question nobody ever asks. As soon as contraction happens, the whole thing switches. Central bankers turn their attention, and move the public’s, toward fighting the thing, making sure it is as shallow and short as may be necessary. Officials pay total focus to getting out of it without ever having to answer for how they got into it.

There are two parts to every recession, it does have an end but also a beginning.

On November 15, 2012, the European Union declared the impossible. The entire continental economy had sunk back into recession, the unusual double dip.

Sure, everything went wrong in 2008 but having “saved” the world from something far worse Economists at central banks had learned a lot. So they said. Why it required a crisis for them to learn anything is an offshoot of the same question no one will ask.

The message was emphasized and repeated – we won’t let it happen again. And then it did happen again, almost without pause.

European officials once recession was declared acted swiftly. Not in solving the mess, rather the only thing central banks may be good for is theatrics. Once the recession declaration became that formality late in 2012, the wheels spun fast. Who should they blame?

The Greeks. Just as 2008 was easily “explained” as something about irresponsible lending and borrowing in the US housing market, 2012 could be laid at the feet of Greece, Portugal, Spain, and Italy. It was PIIGS, they said, an externality against which monetary officials were near powerless to prevent the severe consequences.

German Prime Minister Angela Merkel spent that November as well as the many months which followed in wallowing malaise talking about the wisdom of Greek haircuts, debt restructuring, and little else. On the day Europe’s double dip was confirmed, she said:

I hope the time is near when we can reach the solution that is needed. Of course we did not talk about debt haircuts, you know our view and that has not changed, nor should it.

Paul De Grauwe, an Economist with the London School of Economics, was more orthodox:

We are now getting into a double dip recession which is entirely self-made. It is a result of excessive austerity in southern countries and unwillingness in the north to do anything else.

Mario Draghi gave a speech on November 15, of course he did, in which he literally said the PIIGS directly thwarted his genius policies. The title he gave his sermon was, I kid you not, Financial markets and the disruption caused to the transmission of monetary policy.

Soon, the solvency of the governments of these countries was questioned, and with it the solvency of the financial institutions located there. Within the euro area, less and less money circulated between banks in different countries. Doubts about the future of the euro area in its current form encouraged a speculative movement which lead to further increases in sovereign spreads…

In response, the ECB lowered its benchmark interest rates. Under normal circumstances, such reductions would have been transmitted in a relatively uniform way to households and firms across the euro area. But that’s not what we found.

I know Dr. Draghi, it’s never your fault.

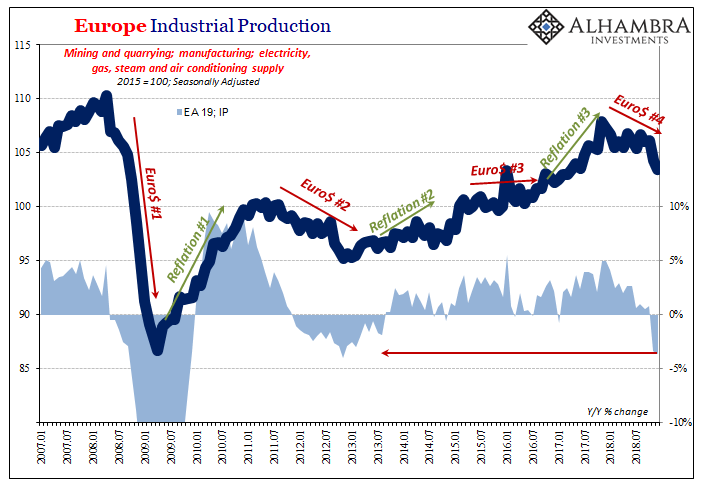

Industrial Production, an important measure of economic health, had been contracting across Europe since the December before, 2011, around the time banks were rumored to be on the brink again. By November 2012, IP had fallen at a 4% annual rate. It was the worst month for European industry during the whole double dip, a contraction in the goods economy that would last for a total of 21 months.

As of this morning, Eurostat reports that once again IP is falling. In December 2018, it had contracted by an estimated 3.6%, after falling 3.3% in November, or about as bad as what was the worst of Europe’s last declared, acknowledged recession. Unlike 2012, officials like Mario Draghi, somehow still the head of the ECB, are still talking about a hypothetical boom rather than this very different economic reality.

As I wrote yesterday, when you screw up a few years here or there you can be realistic about things (even as you CYA). If you mess up a decade or two, there will only be fairy tales.

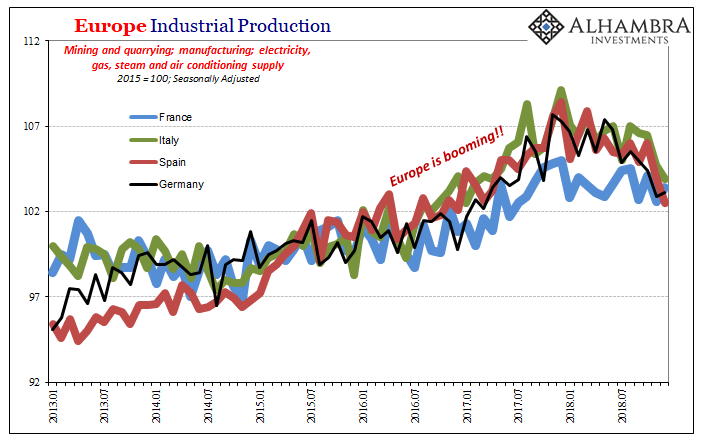

The growing contraction, already one year in length, has been downplayed at every juncture. First, it was emissions. Then it was drought. Just Germany. All temporary.

But the downturn keeps getting bigger and broader, the rate of decline increasing while more and more national economies are sucked into it. In December, German IP was rather steady; it was Italy and Spain, among others, who plunged.

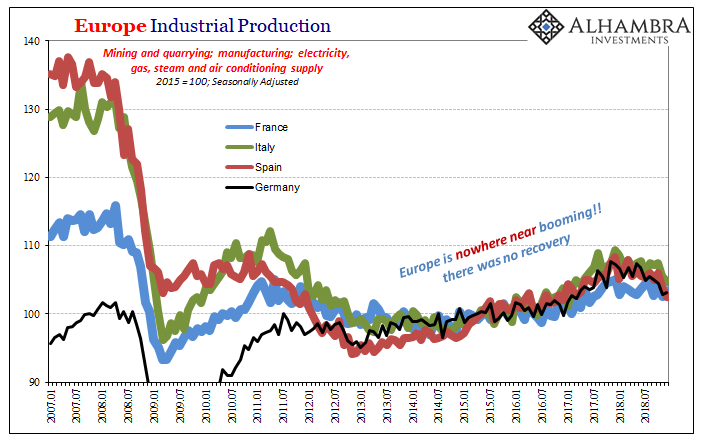

If this latest contraction is ever declared, which is somewhat of a longshot nowadays, we will be invited to put these two events into separate categories. November 2012 was, after all, six years ago. Had there been an actual recovery in between, that would be the right thing to do. No two recessions are the same.

Without any recovery at all, though, we are forced to consider not recessions plural, but a singular instance of something else. A triple dip in Europe lasting eleven years in total all due to a constant, common factor. Single contraction of varying intensity.

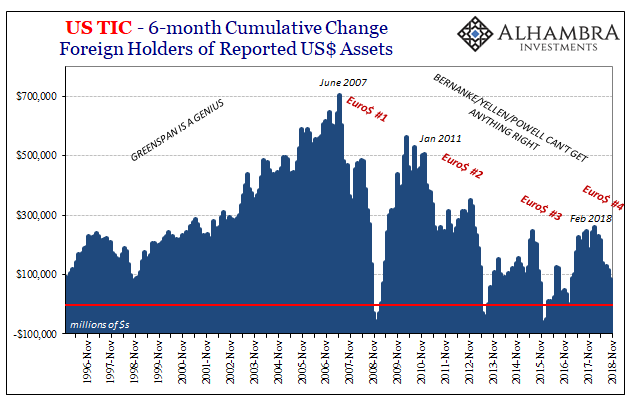

Maybe it never was really about PIIGS. Yes, sovereign debt was a problem and the timing of its reckoning, which turned out to be mild, all things considered, was unfortunate. That’s not what congested Draghi’s monetary channels. Another way of saying clogged monetary transmission is, the policies didn’t work.

Claiming that they were interrupted by some gigantic externality is admitting the same thing only without accepting blame for the lack of success. Europe’s economy fell sharply in 2008 and 2009, didn’t really recover in 2010 and 2011, was back in recession in 2012 and 2013, and then spent the next few years with mildly positive growth (only mildly affected by Euro$ #3 which focused as much on China and Asia).

What’s to blame for 2018?

That question needs to be answered honestly before getting to the next one: how bad might 2019 be? Europe’s economy is already in big trouble, by extension the global economy clearly unhealthy. It was never about PIIGS and subprime mortgages. Europe’s economic problems in 2012, as 2008 or 2018, weren’t even European.

Stay In Touch