You know things have really changed when Economists start revising their statements more than the data. What’s going on in the global economy has quickly reached a critical stage. This represents a big shift in expectations, a really big one, especially in the mainstream where the words “strong” and “boom” couldn’t have been used any more than they were. If you read nothing other than Bloomberg, it’s as if some alien force has descended upon the world and completely spun it around the other way.

With that in mind, now they say 2017 wasn’t really all that:

The cyclical upswing that took hold of the global economy in mid-2017 was never going to last. Even so, the extent of the slowdown since late last year has surprised many economists, including us.

“Us” being a couple of Bloomberg Economists who are now in the uncomfortable position of writing about their forecasting model striking the lowest posture since 2009. “The global economy’s sharp loss of speed through 2018 has left the pace of expansion the weakest since the global financial crisis a decade ago, according to Bloomberg Economics.”

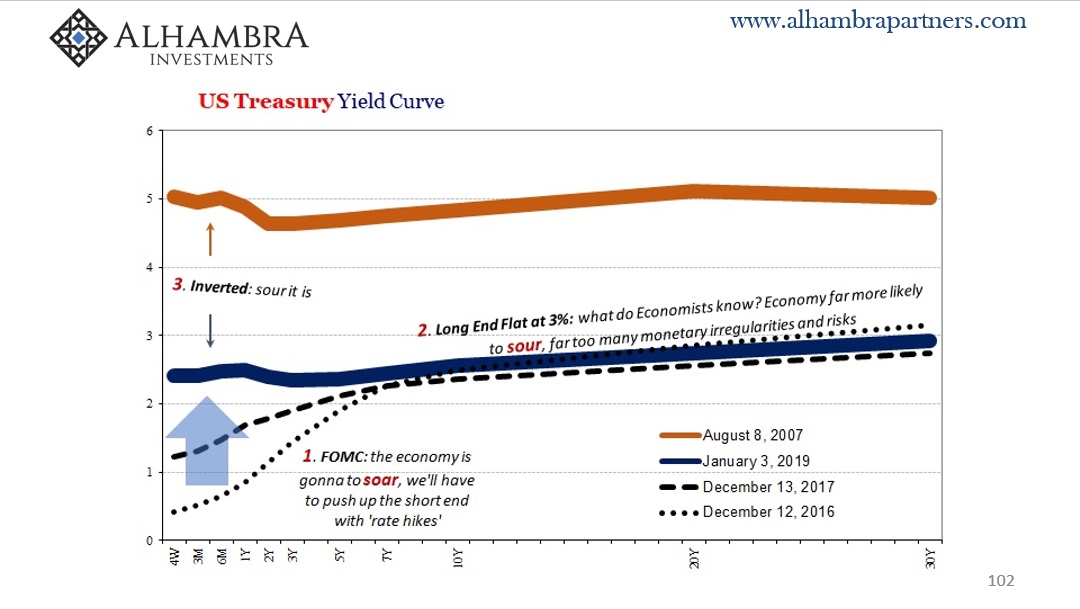

The probabilities have all changed, only not as much as you might have expected. Bond curves around the world have been uniformly skeptical about this last upturn; more likely to sour than soar. As more and more data comes in from key places around the world, sour appears to have been the correct interpretation. Ignore the flattening curves, they said, just term premiums.

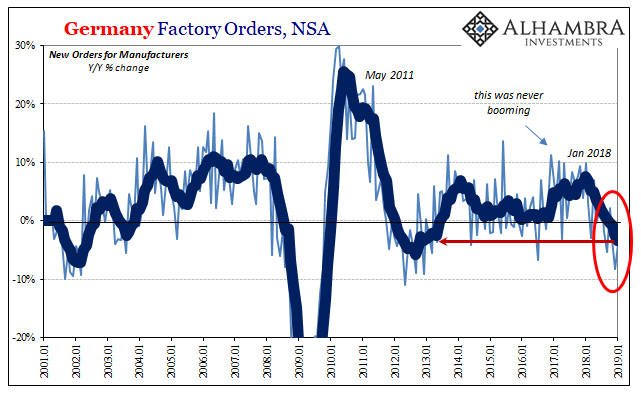

Germany is one such bellwether. Whether you are partial to Korean nukes, trade war rhetoric and uncertainty, even the inflationary scenario formerly of Draghi and Powell, “whatever” it was it smacked the German goods economy first and hardest. Since, at the margins, this particular piece derives much of its strength from selling stuff to the rest of the world, if suddenly Germany’s factories are scaling back we know what that says about the true state of the global economy.

The country’s chief statistical agency, deStatis, updated Factory Orders and Industrial Production. These were down sharply in December 2018 according to last month’s initial estimates. Revised figures suggest the plunge wasn’t as bad, though still a plunge. Whereas factory orders had originally been figured lower by more than 10%, now it is thought they declined by 8.3%.

In January 2019, orders fell by nearly 4%. While that may sound like an improvement, it is actually the continuation of noisy short-term changes natural to factory orders. These fell by 5.4% in September 2018 and then rose by 2.2% the following month in October. The 6-month average, on the contrary, has continued to decline since last January. Lower lows, lower highs.

At -3.4%, the average is now the weakest since December 2012 – the last time Germany, and all of Europe, had been declared in recession.

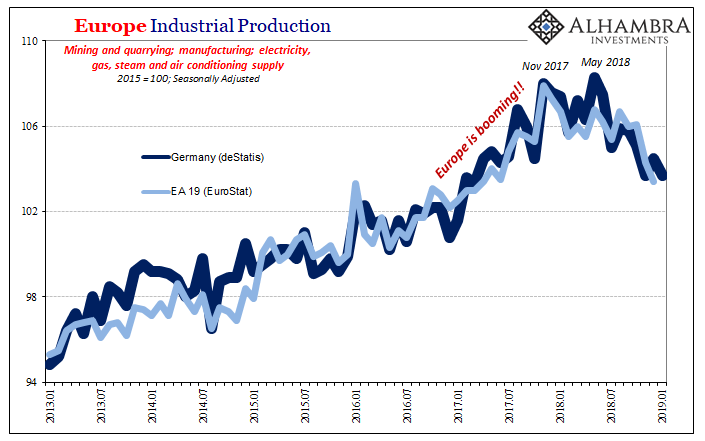

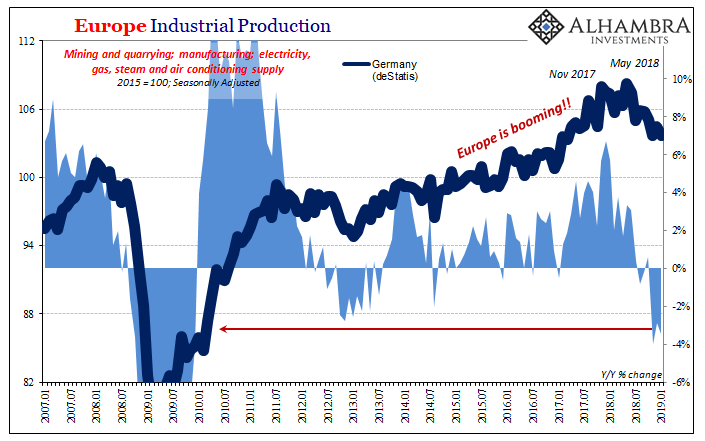

In terms of current production levels, German industry has been falling since last May. Again, May 29 looms in the data just as it does on market charts.

Eurostat will update its version of Industrial Production later in the week for Europe as a whole, for now deStatis suggests that Germany hasn’t been able to gain any ground. With this economy leading Europe into the red, this is one reason why Bloomberg’s Economists are now revising themselves on that whole 2017 boom thing – if it really had been one, Germany and the rest of the world wouldn’t have been facing this mess which is already nearly a year in length.

Year-over-year, German IP has contracted in each of the last three months, five out of the past six. And, as you can see above, the level of decline in these latest three is worse than at any point during the 2012 recession. The last time Germany’s vaunted production engine had struggled to this degree it was the Great “Recession” plaguing the world economy.

At least that much is consistent with Bloomberg’s modeled reassessment, “the weakest since the global financial crisis a decade ago.”

In other words, pretty serious already. What that means at this stage is the probability of avoiding a big downturn is diminishing by the month, not much upside to begin with (as Economists are now saying). Downside economic risk therefore takes its place. This includes more than just its appearance, as greater negative skews also mean the potential for a lower (maybe longer) ultimate trough for this eurodollar cycle.

Sure enough, the fourth one.

Stay In Touch