Last August, the Senate confirmed Richard Clarida for both a position on the Federal Reserve Board of Governors as well as to be installed as its Vice Chairman. Clarida had been chairman of the Economics department at Columbia as well as working for PIMCO where he had served the investment company as its Global Strategic Advisor since 2006. You can already see where this is going.

His last blog post for PIMCO was published in January last year, several months before his nomination to the central bank. Included in it was all the usual stuff.

Going into Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen’s 32nd and final meeting, neither we nor the markets expected the Fed to make much news. Of note, however, in its statement after the meeting on 31 January, the Fed acknowledged recent firmer economic data and expressed confidence in inflation moving toward the 2% target later this year.

It is very interesting that in January 2018, Dr. Clarida’s view was for “slightly higher inflation” than what the Fed acknowledged. One year or so later, now as its highest-ranking Economist, his first major project will be to lead an exhaustive study of the Fed’s entire toolkit.

They aren’t quite admitting they really don’t know what they are doing, but, yeah, they are quietly admitting they don’t really know what they are doing. Something isn’t adding up. They all allowed themselves to be bamboozled last year, 2018 not at all finishing up the way it was universally expected.

Late last month, Vice Chairman Clarida appeared at the University of Chicago’s US Monetary Policy Forum in New York. It’s not that officials are unhappy with monetary policy, he said, it’s just that everything changed around 2008 and maybe that might mean something – in 2019.

Indeed, we believe our existing framework has served us well, helping us effectively achieve our statutorily assigned dual-mandate goals of maximum employment and price stability. Nonetheless, in light of the unprecedented events of the past decade, we believe it is a good time to step back and assess whether, and in what possible ways, we can refine our strategy, tools, and communication practices to achieve and maintain these goals as consistently and robustly as possible.

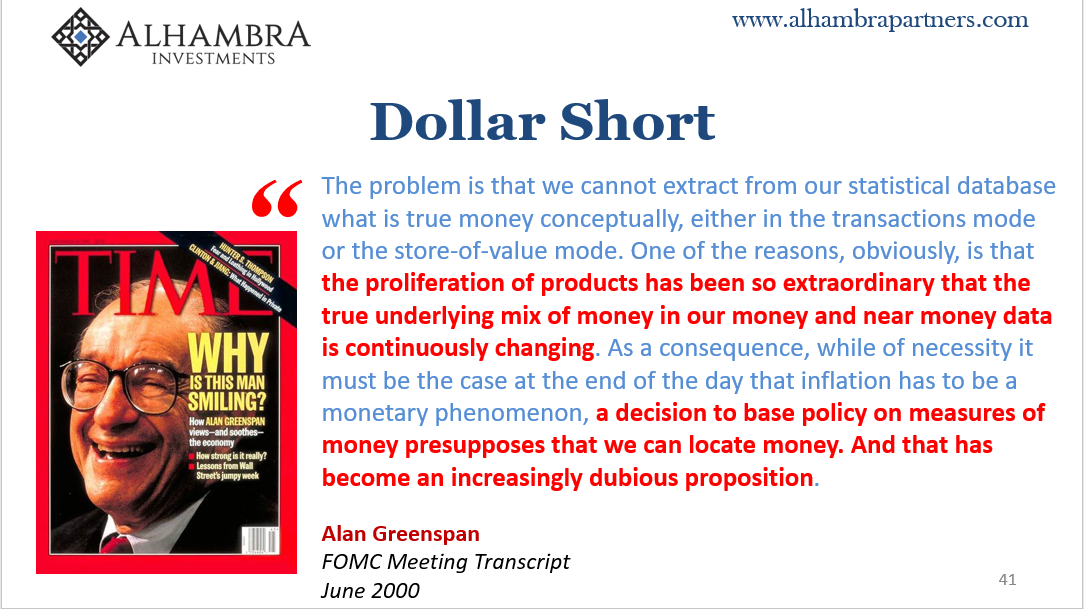

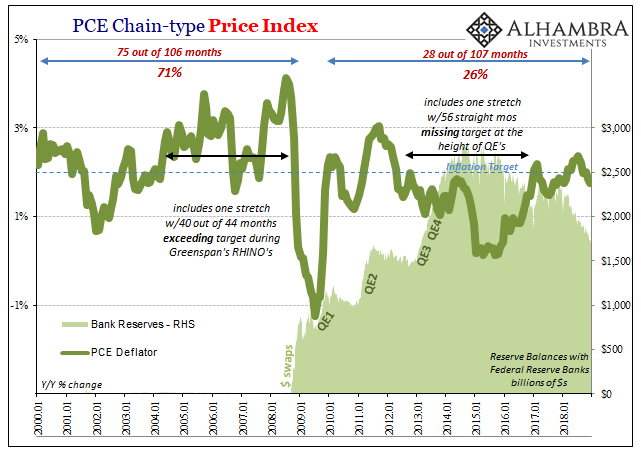

Among these “unprecedented events”, somehow the Federal Reserve managed to miss its inflation target an awful lot. In fact, they rarely, if ever, saw enough of it to meet their self-defined definition of price stability. This is no small thing, as Chairman Greenspan once said (it’s between the two highlighted sections below):

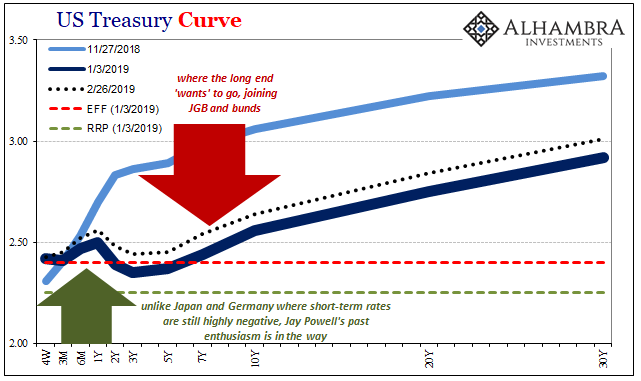

The problem, and the Fed isn’t admitting there is one, could center around R*. Always R*. Without reviewing for the nth time what this really means, policymakers are concerned that given this “something” that is wrong with the economy there is, in their view, a small chance for big problems. More big problems, that is.

If the federal funds rate can’t get higher than 2.5%, for example, as appears to be the case right now, how much “stimulus” will there be in going back to zero during the next recession (way, way, way out in the future, of course)? Should you know anything about the last crisis, your honest answer is – none of this matters.

Ben Bernanke, after all, started out his “stimulus” from 5.25% and it didn’t make the smallest bit of difference, did it?

That’s ultimately what’s going on here. Underneath, there is a very real concern on the part of officials that maybe they don’t really have a good grasp of, and therefore the right tools for, how things actually work. Again, something isn’t adding up.

To inadvertently advertise this lack of understanding first, Dr. Clarida provided a very clear example of why, ultimately, this review, despite acknowledging a little bit of reality, will lead them nowhere:

In addition to assessing the efficacy of these existing tools, we will consider additional tools to ease policy when the ELB is binding. For example, as is presently Bank of Japan policy, the FOMC could, when the ELB is binding, establish a temporary ceiling for Treasury yields at longer maturities by standing ready to purchase them at a preannounced floor price.

When things might get going to the bad side, the Fed will consider it stimulus if it…puts a ceiling on UST yields? Huh? Sorry guys, and gals, you have no idea how interest rates work. And that really says something about everything, starting with inflation and economic expectations.

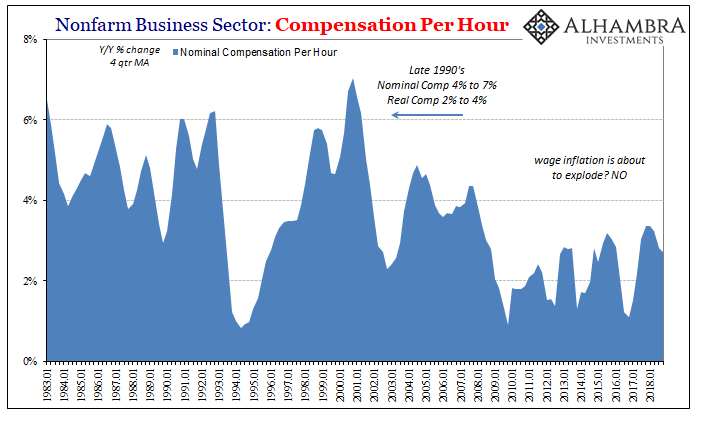

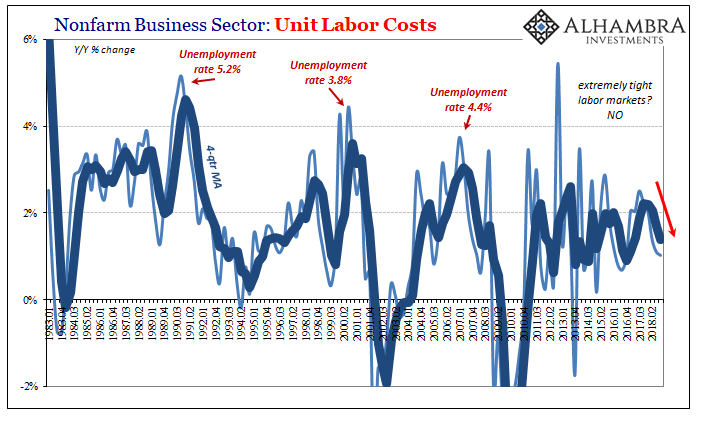

The more immediate issue is back to current levels of inflation. To review once more: unemployment rate says tight labor market which suggests heavy competition for workers, this bidding war drives up wages, companies pass the increased costs to customers, voila, accelerating CPI, or PCE Deflator, which confirms the economy is actually booming and monetary policy a complete, total success.

This didn’t happen last year despite everyone’s expectation that it would, Clarida’s included. In light of this pretty big setback, the Fed is going to chase its R* rabbit right back down Alan Greenspan’s conundrum filled, series of one-year forwards, rabbit hole. Good luck with that.

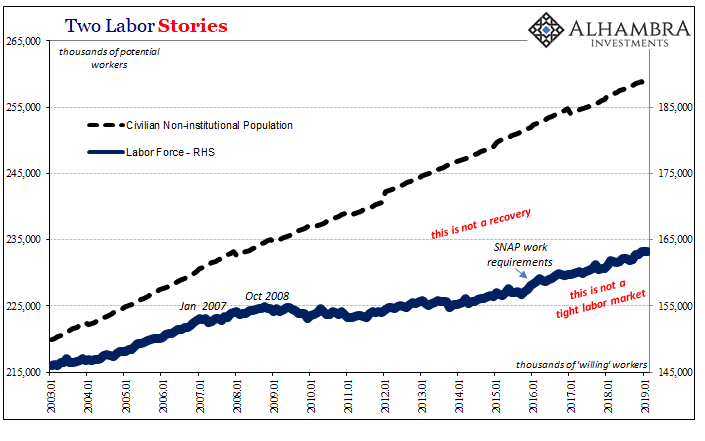

Their big problem is much simpler; the unemployment rate is faulty. The evidence for it being this way is overwhelming. You could make the argument that the labor market is robustly tight, and still there is no inflation because companies can’t pass along higher wages to consumers. This still doesn’t add up to a booming economy, but at least the unemployment rate would be consistent.

But we continue to find no evidence for the first part; where’s the wage explosion? It’s just not there. The BLS, in addition to its February payroll report released today, released yesterday updates of some of the more detailed compensation statistics for Q4.

Nominal Compensation per Hour rose by just 3.9% year-over-year in the fourth quarter of 2018. That’s hardly indicative of a good let alone superlative labor market. It remains historically depressed.

Growth of Unit Labor Costs slowed for the fifth consecutive quarter – at the very same time the unemployment rate dropped to, and then below, 4%. In Q4, this measure was up just 1% year-over-year, the smallest increase since Q3 2016.

Forget all the inflation stuff, don’t bother about R*. There is just no evidence the labor market is even tight. What that means, I’ll return to Janet Yellen at least her personal view in 2014:

Ms. YELLEN. But when we see diminished labor force participation among prime-age men and women, that suggests something that is not just demographic. And so my personal view is that a portion of the decline in labor force participation we have seen is a kind of hidden slack or unemployment.

If what she said almost half a decade ago remains true, this hidden slack, and that’s what the evidence says, the Fed’s got everything wrong; inflation, labor market, economic situation, right up to the macro cause (Keynes: the worse evil of deflation).

Vice Chairman Clarida is forced to reckon a review of monetary policy because of these factors. And he’s already shown, what we all know, he’s not really going to review monetary policy. These “the unprecedented events of the past decade.” No matter what Euro$ #4 turns out to be, I’m already guessing for a Euro$ #5 and a race to see which goes lower, the unemployment rate or the yield on the UST 10s. No ceiling required.

Stay In Touch