The Economics textbook says that when faced with a downturn, the central bank turns to easing and the central government starts borrowing and spending. This combined “stimulus” approach will fill in the troughs without shaving off the peaks; at least according to neo-Keynesian doctrine. The point is to raise what these Economists call aggregate demand.

If everyday folks don’t want to spend – because a lot of them can’t – then the government will spend on their behalf. And the central bank will make it easier on everyone, including the government, to borrow while doing it.

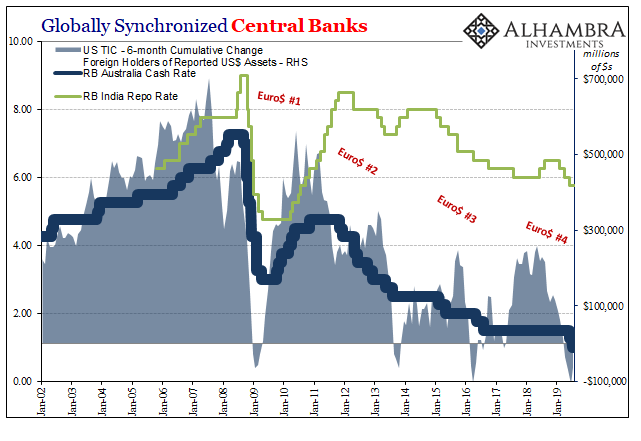

Faced with the early parts of what would only later be called the Great “Recession”, that’s just what had happened. Rates were cut worldwide and governments sprang into action.

Among them, people today have largely forgotten (that’s how well this stuff works) about the US’ first modern experiment with helicopter money. The Bush tax cuts, financed by a greater deficit, were rather more extreme than many had been comfortable with. Some were otherwise comforted by the administration taking the economic problem more seriously.

The German response to that as well as what other European governments were doing and considering was typically German. They run a very tight ship in that country; balanced budgets are part of the deal.

Even as late as November 2008, Chancellor Angela Merkel was gaining the reputation for being Frau Nein for saying no to every proposal; famously telling her party’s congress “we’re not going to participate in this senseless race for billions.” Perhaps it was the widespread belief that German industriousness as well as its industry would allow Germany to ride out the growing storm without much damage.

Not even two months later, however, Merkel was unveiling the country’s largest government spending program since World War II. Equivalent to about 1.6% of GDP, it was €50 billion in spending and tax cuts (including a Bush-like helicopter component, a one-off €100 child “bonus”) financed by a €36.8 billion increase in government borrowing.

Economists will tell you it saved jobs in Germany, and therefore it must have been effective to some degree. Regardless, the Great “Recession” because of the Global Financial Crisis ran through Germany all the same.

The “stimulus” debate isn’t really about stimulating the economy. It is seeing just how much government and central bank officials are aware of their surroundings (and then observing how powerless they are to do much about them when they go bad). In other words, Merkel seemed oblivious to Germany’s economic peril in November 2008 but had finally gotten the picture by January 2009.

The truth of the matter is her country’s fate was sealed long before then. As I wrote recently, for the first emergency TAF (dollar) liquidity auction held in December 2007:

The biggest borrowers, though, were other sorts of ostensibly New York banks; firms like, Landesbank Hessen-Thurin, Bayerische Landesbank, Dresdner Bank AG, Deustche Zentra AG, Landesbank Baden Wuerttemb, and WestLB (the LB stands for, as you probably guessed, landesbank). Those six “New York” banks alone accounted for half of the $20 billion allotted. Given the style of these names, you might already be sensing a theme.

German banks had run into something of a serious dollar squeeze during the summer before. The Global Financial Crisis was really a global dollar shortage and much of it centered upon Germany’s financial institutions. Though the Germans surely were productive and industrious, frugal and financially conservative, it didn’t matter because they didn’t save and couldn’t manufacture dollars.

The fatal flaw in the design.

Frau Nein caught a lot of heat for her flip flop. Some criticized her for not holding firm (one opposition party leader, Otto Fricke, called her Finance Minister Peer Steinbrück the “minister of record debt”) while the vast majority thought her hopelessly, mistakenly optimistic. After all, it was Steinbrück who had just accused the British of “crass Keynesianism” before then turning around and embracing the sentiment “we are all Keynesians now.”

That’s what the eurodollar does – it will turn even the most reluctant and prudent among officials into reckless spendthrifts not because it will work but because they just don’t know what else to do. Their big mistake is in believing the central bank has the other piece covered – that whole business of monetary easing.

If the central bank is easing and the economy is failing anyway, no one ever stops to reconsider Square One: maybe the central bank really isn’t easing. They say they are, but is there any proof (besides term premiums)?

Angela Merkel is still there in Germany, a testament at least to some pretty sharp political skills if nothing else. She survived the Great “Recession” when many did not, and seems to have learned a thing or two along the way.

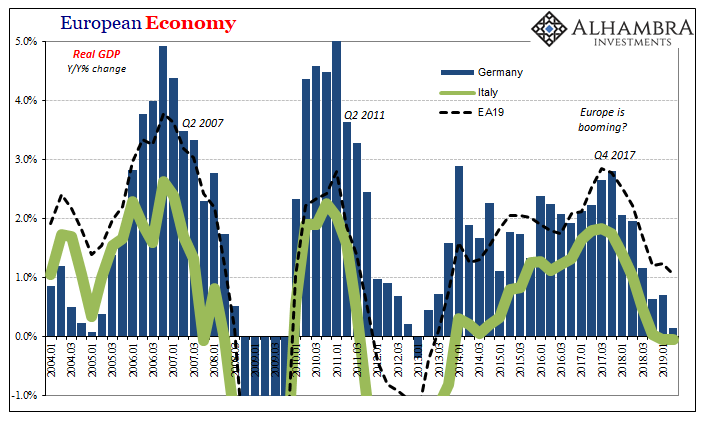

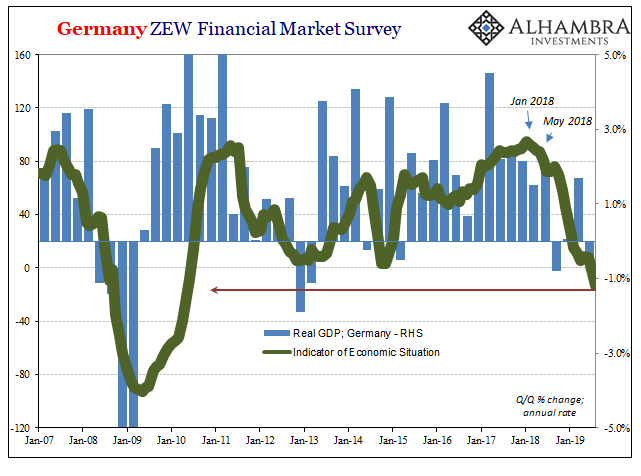

Though Germany’s vast manufacturing and export sector has been in its own recession for more than a year, there’s only now the general feeling the entire German and European economy is about to take the plunge, too.

Rather than remain steady as she did throughout all of 2008, Merkel has pre-softened this time around:

On Sunday, Finance Minister Olaf Scholz suggested the government would aim to muster 50 billion euros ($55 billion) of extra spending in case of an economic crisis. Last week, Chancellor Angela Merkel said the economy is “heading into a difficult phase” and that her government will react “depending on the situation.”

The media tells you this is a positive sign for things to come. Is it? Or might it instead be just another escalating warning?

The ECB will be, we are told, also doing its job. Monetary “stimulus” is on the way, almost certainly to arrive in several weeks.

The Germans are far from alone in their struggle. What was supposed to have been a year filled with global rate hikes and normalization has instead been one half-completed already with rate cuts, dovishness, and, yes, more “easing.” Even the hawks at the Fed have turned chicken.

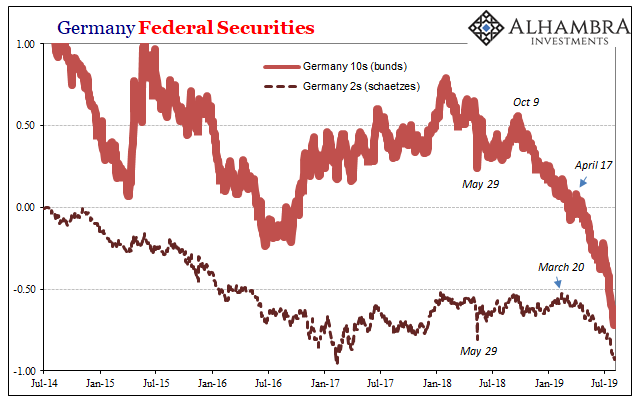

And what does the local as well as global bond market make of all this? Not much. As the tide of “stimulus” rolls in, yields plunge all the same regardless.

While Mario Draghi was on his celebrated retirement tour (Europe’s booming, baby) bonds were the one place that had said to the Italian ECB chief, hey, you’ve got a big problem looming in Germany and therefore all of Europe. The alarm was immediately and flippantly dismissed. It has since been proven correct about the German economy; it really is in serious trouble.

There’s an entire array of statistics that show this, but now that its government is one small push away from crass Keynesianism again there can be no doubt. Stimulus here has come to signify nothing more than how officials don’t know what else to do about what must be a very serious problem.

It’s not stimulus. It’s not just Germany. There is only dollar. It is the eurodollar’s world. We are all still just trying to live in it.

Stay In Touch