The Federal Reserve has been maintaining statistics on American industry for nearly as long as there has been a Federal Reserve. The first entry in the data series on Industrial Production is for the month of January ’19. Not 2019 but 1919. With over a hundred years of relatively consistent data, matching up very well with overall trends in the US economy over an unusually long period, it’s no wonder IP is at the top of the list of key indicators.

The NBER cites it as one narrow economy measure for helping its Business Cycle Dating Committee determine any cyclical change.

The Committee also may consider indicators that do not cover the entire economy, such as real sales and the Federal Reserve’s index of industrial production (IP). The Committee’s use of these indicators in conjunction with the broad measures recognizes the issue of double-counting of sectors included in both those indicators and the broad measures. Still, a well-defined peak or trough in real sales or IP might help to determine the overall peak or trough dates, particularly if the economy-wide indicators are in conflict or do not have well-defined peaks or troughs.

According to the latest IP estimates from the Federal Reserve, the NBER has been put on notice. For the month of April 2019, US industrial production declined 0.5% (seasonally-adjusted) from the level in March. It was the third monthly decline in the past four months, not a good showing at all for this recent “dovish” central bank turn.

Maybe economy-wide indicators don’t yet form a well-defined peak, but it is getting pretty defined in terms of industrial production.

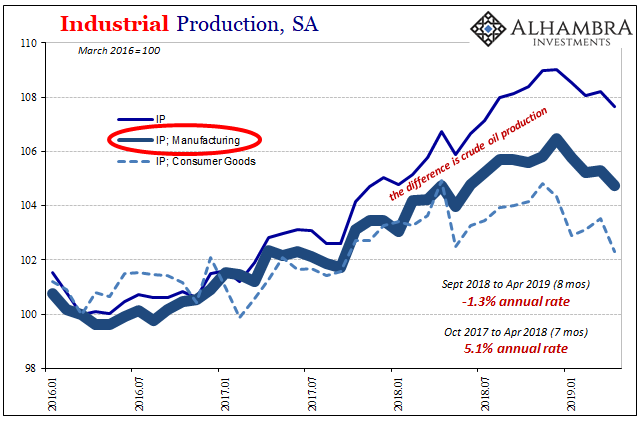

Year-over-year, the comparison is still positive but barely. Last month’s overall index was just 0.9% higher than the value estimated for last April. The only segment keeping it positive, for now, is crude oil.

Mining and production of oil has only cooled off a little from its blistering pace last year. Production volume is still growing at near 15% year-over-year. If not for shale and WTI’s rebound in 2019, the downward bend in the IP index would be more substantial than it already is.

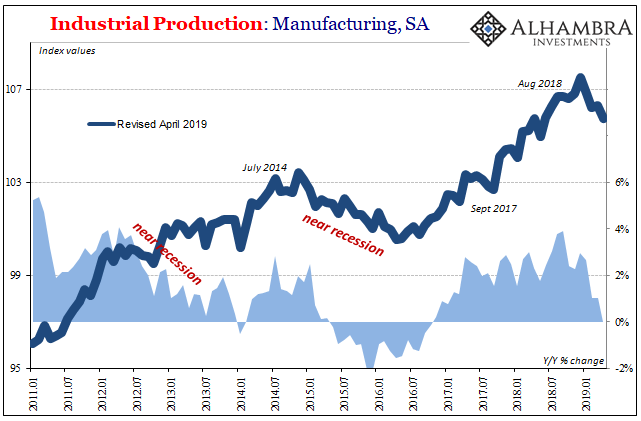

In several key components, however, the minus signs have shown up. Manufacturing production, for example, has also been lower in three of the past four months, too. It’s slump dates back to last September. Over that eight-month period up to and including April, IP Manufacturing is down at a 1.3% annual rate. When compared to April 2018, the manufacturing index is just a slight fraction negative.

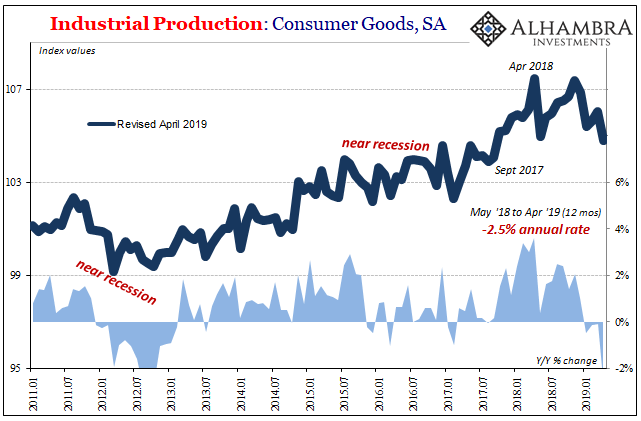

In terms of the production of consumer goods, the numbers get much worse. The level of output peaked one year ago back last April. Since then, up to April 2019, the index for IP Consumer goods has fallen by 2.5%. That’s the largest decline since 2012 (below).

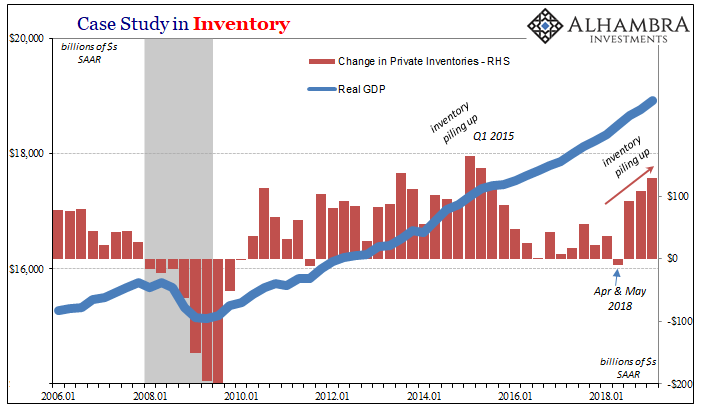

It backs up the retail sales figures which have been suggesting consumer spending is increasing at levels more associated with recession than anything else. This is also consistent with GDP data for Q1 which, despite the headline, indicated a substantial and substantially unwanted accumulation of inventory.

Sales tail off, inventory piles up, production levels are curtailed. Classic recession pattern.

When total IP is contracting, you can be sure it’s very serious. Before 2015, it had always meant recession beyond a certain threshold. That level was met during the “manufacturing recession” of Euro$ #3. It remains the only time when a significant decline in IP over more than a few months didn’t coincide with an NBER dating.

Euro$ #4 appears to be even more serious still. During the last one, much of the negative monetary focus globally fell upon Asia and China in particular. The US was lucky, as was Europe, spared the full weight of the disruption which truly devastated a lot of EM countries. They’ve yet to recover, a significant factor beyond the growing economic costs.

This time, there may be no safe harbors. For much of last year, the same decoupling fantasy as 2015-16 was reused; the US boom would protect the American economy from suffering the same weakness elsewhere which was being recognized even by central bankers.

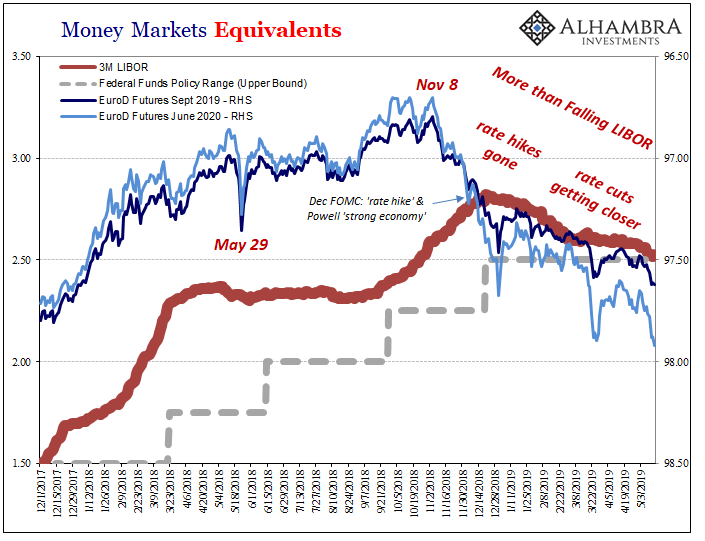

But, as key economic accounts like IP and retail sales demonstrate, that may never have been true at any point. This downturn associated with Euro$ #4 goes back in some places to the early parts of 2018 – the same months when “overseas turmoil” first materialized in April and May (29). It’s not overseas, just turmoil.

Germany, Japan, China, and the US. All are simultaneously showing signs consistent with recessionary forces. This is what I wrote back in September 2018 just before the market whirlwind:

From 2003 to 2009, it went: globally synchronized growth, decoupling, globally synchronized downturn. From 2010 to 2012, it went: globally synchronized growth, decoupling, globally synchronized downturn. From 2013 to 2016, it went: strong global growth (not synchronized), decoupling, synchronized downturn.

Last year to this year, it has gone: globally synchronized growth, decoupling. What comes next?

The point that eludes Jay Powell and the end-of-the-30-year-bond-bull crowd, the very spark of realization that ignited the market chaos, is that there never is any decoupling. Like an outbreak of disease, once the monetary malady starts it will eventually contaminate everything. And like any epidemic, some survive infection with less harm while others are not so fortunate.

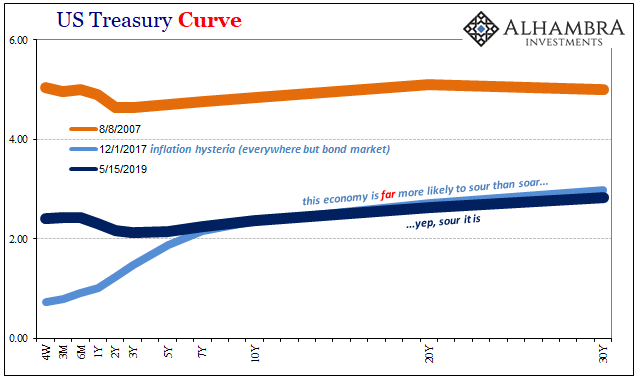

In other words, the bond market is being proved right not just about curve inversion over the last several months but going back years. In 2017, during the very height of inflation hysteria, the bond market stood back and said, NO. The flattened curves more importantly flattening where they were, around 3% nominal, were unyielding about the economy’s chances.

No matter Janet Yellen and Mario Draghi. Pay no attention to the unemployment rate. More likely to sour than soar.

This is not what Economists had in mind for globally synchronized growth. It is, however, what the eurodollar has always had in mind. A chronic condition which will only leave the global economy highly susceptible to reverse. No recovery will be possible. Trust the curves.

Jay Powell and those like him have no idea what’s going on offshore in global money. There’s your decoupling.

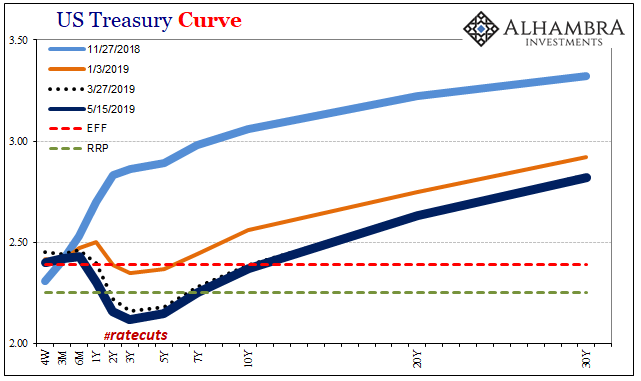

With IP one-third of the way through 2019 suggesting what it does, the only question left to answer is, just how sour? A partial reply is being provided right now by related markets. Rate cut(s) sour.

Stay In Touch