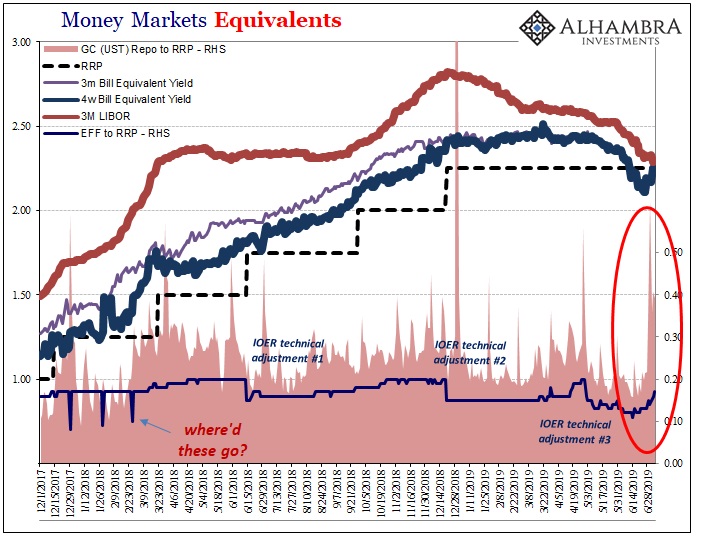

As of trading on Friday, federal funds for the third time is now back to above where all this began. For much of 2017 and Reflation #3, the effective federal funds rate (EFF) remained steady at 16 bps above the RRP “floor.” Apart from month-end dumpings, it was consistent and predictable; the best of times, or at least what passes for them in this day and age.

As of July 5, 2019, FRBNY puts EFF at 2.42%. To give the relevant context, in case you haven’t been following, that 17 bps spread today includes three “technical adjustments” to IOER. In other words, IOER, the so-called ceiling, is 15 bps lower than it was for EFF being higher than when this all started.

There’s a lot that is going wrong in those 17 bps (or the 15, however you want to look at it).

It isn’t the payroll reports which are going to push Jay Powell to start cutting rates. It can’t be now, at least given the last one and how markets are still absolutely certain Powell moves at the end of this month.

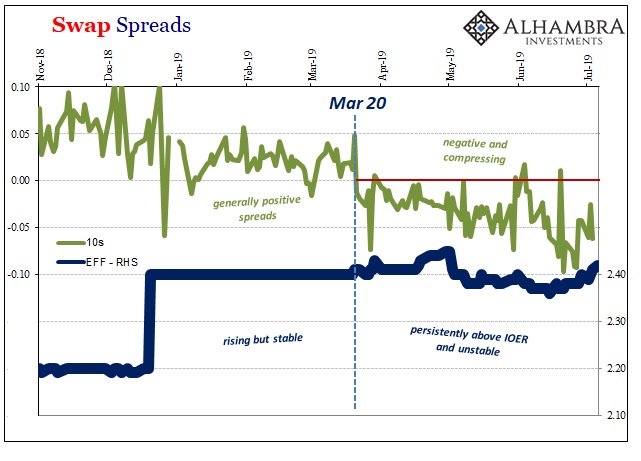

What seems to be spooking the pile (there’s not much left of actual curves in 2019) is monetary before economic. We might see negative numbers for the Establishment Survey this year, but not likely before whatever is truly going on in the eurodollar world shows up first.

Economists equate recessions and the like with shocks. There’s an awful lot of worry in bonds right now about that very thing. Some are saying this is way overblown; too much pessimism from the usual doom and gloom suspects. It doesn’t matter that global bonds are an order of magnitude greater than the stock market, all of them, according to the mainstream view Cassandras apparently can wield influence anywhere.

It’s easy enough therefore to begin in India:

Sales of riskier rupee corporate bonds have all but dried up in recent months, in another negative for India’s slowing economy as companies struggle to raise cash.

Issuance of notes graded A+ and lower plunged 84% last quarter from a year earlier to 22.6 billion rupees ($329 million), the least in five years, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Borrowing costs have also jumped for issuers with lower debt scores, as a crisis in India’s shadow banking sector saps investor demand for riskier securities.

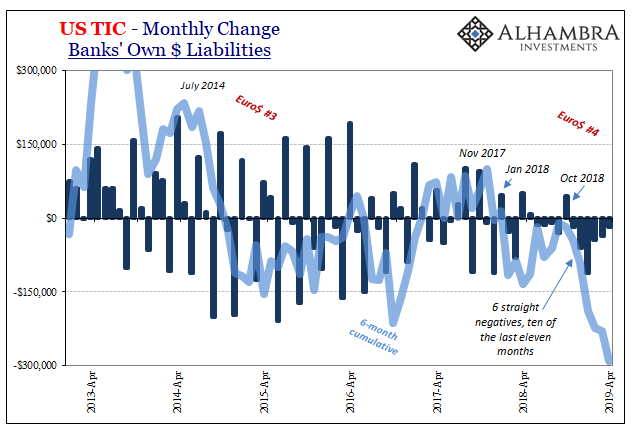

India’s rupee has been given shelter only by the fact that the rest of the world is perched equally precariously. Unlike 2015 and Euro$ #3, Euro$ #4 is taking no prisoners and offering little economic quarter to anyone. That’s the importance of EFF – four years ago the global dollar shortage was certainly widespread as the term implies but not so uniform; more overseas global than domestic.

In 2019, it is playing out as just plain dollar shortage. While EFF and swap spreads signal how close it hits to the dollar’s presumed home, there’s no shortage of indications of escalating “overseas turmoil”, too.

In Turkey, Murat Cetinkaya has been sacked. The country’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan decided to remove the central bank’s governor apparently having had enough of interest rates. Last September, officials at Türkiye Cumhuriyet Merkez Bankası increased their benchmark policy rate by 625 bps. It was, even for Turkey, an extreme move and it was actually the lesser of the two last year.

With the lira in freefall, Cetinkaya merely did what the orthodox central bank manual calls for. Currency-driven inflation is lower in 2019 than the record highs recorded in 2018 – but so is Turkey’s economic prospects plunged into recession. Therefore, Erdogan’s ire.

Over in Malaysia, a credit crunch is emerging in that country, too.

The case is growing for Bank Negara Malaysia to bolster the economy with another interest-rate cut — and to provide some much-needed encouragement for inflows to the ringgit bond market.

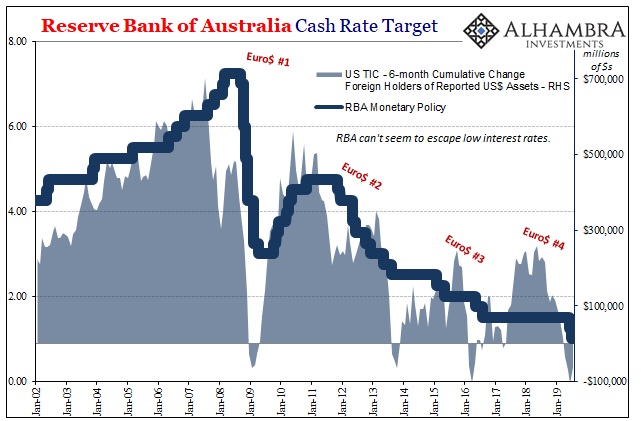

Less than a week ago, the Reserve Bank of Australia cut its policy rate for the second time in as many months. Governor Philip Lowe added, “that the risks to the global economy are tilted to the downside.” He blamed these risks on “trade and technology disputes” because, as a central banker, he really has no idea what’s going on with the global monetary system.

The list goes on and on, what’s above merely a sample from the last week or so.

While national media in the US narrows in on the June payroll report (without realizing how substandard it really was, even for recent times) the downside case continues to build. What I wrote in January 2016, about why this thing continues, could have been written today, last month, or last December.

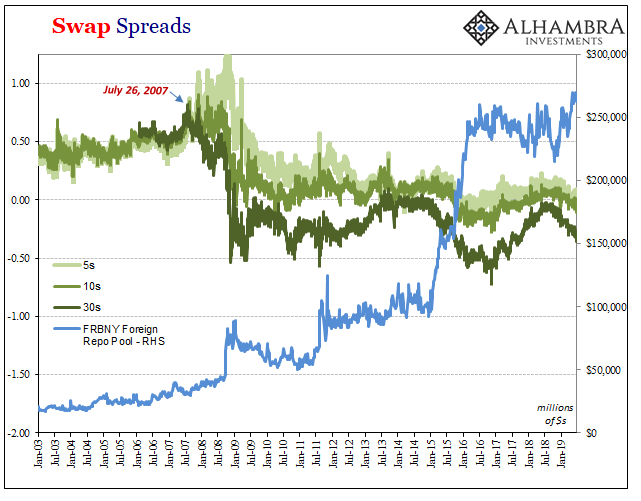

It is an amazing coincidence, then, that the world is suddenly short of dollars while the biggest banks are no longer interested in trading them and the financial products they support. You can chicken and egg this all you want at this point, it matters little whether it was the lack of recovery that kicked off the withdrawal and created the challenging market conditions or the challenging market conditions that killed the recovery and forced the retreat. In some ways, it’s all one and the same bound together by calculations of expected volatility; my own view is and has been that banks saw the fruitlessness of QE and where the economy was going (bond market, inflation expectations) and precipitated weakening still further the hollowed out husk of the former eurodollar system. The events of 2007 and 2008 left just such a fragile existence.

One of the primary subjects of that article was a key bank which had just reported less-than-desirable quarterly numbers. In fact, it was Deutsche Bank which had just then used the term “challenging market conditions” as if that would justify its losses. It was nothing more than a euphemism for “dollar shortage we can’t accurately characterize and aren’t remotely prepared for even though we are collectively responsible for it.”

In recent weeks, as bond yields tumbled the world over, that same bank has unveiled a bankruptcy-like restructuring plan in its “trading” units which has included a “bad bank” component. Initially reported to be about €50 billion in total assets, the firm itself reported over the weekend a scale of now €74 billion.

Maybe you start to see why German government officials were keen to link up DB with anyone, including equally questionable Commerzbank. And then you don’t stop there, connecting the dots for an incestuous system that at once relies on banks like DB to provide “liquidity” and spread it all over the world.

If some large-scale conflict was to shut down the Straits of Hormuz for an extended period of time, what would happen to the price of oil and the global economy in that case? An oil shortage of that kind would be a huge drag and then some – on everyone.

This is a very real concern, but one that is still theoretical.

A large-scale (and lingering) defect shutting down or seriously incapacitating one or several key parts of dollar redistribution pieces isn’t theoretical. We can’t see and directly observe the empty eurodollar tankers piling up in ports or the choked off flow of monetary resources, but we can absolutely detect and perceive their effects nonetheless – especially in the price of “dollars” more broadly and the second order problems which inevitably (and repeatedly) result.

The bigger market isn’t worried about US payroll reports. The pessimism at the very least should be taken seriously. What is the only thing which explains all the facts: India credit, Turkey’s central bank politics, Malaysia’s bond market, Australia’s rate cuts, Deutsche Bank’s sudden affinity for stuffing assets on someone else’s balance sheet, and federal funds?

Even Jay Powell knows his second half rebound is in real jeopardy; even if he can’t (and may never) figure out why.

Stay In Touch