Unable to tackle effective monetary requirements, bank regulators around the world turned to “macroprudential” approaches in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis. It was mostly public relations, a way to assure the public that 2008 would never be repeated. A whole set of new rules was instituted which everyone was told would rein in the worst abuses.

Among the more prominent of these was Basel 3’s leverage ratio. Of the banks that failed or nearly failed more than ten years ago, they did so with what seemed to authorities hidden leverage. Their capital ratios, for the most part, were fine. Yet, the amount of leverage each institution had employed was beyond imprudent.

The reason for what may seem to be a contradiction was simple: regulatory arbitrage. Banks found a way to game the rules. Employing all sorts of mathematical transformations, including the heavy use of credit default swaps (regulatory capital relief), firms manipulated their risk-weighted assets regardless of gross exposures. To put it simply, they made risky activities seem much less so.

And it all fell within the rules.

Another accounting trick, so to speak, was window-dressing. The most famous, and questionable, was Lehman Brothers’ Repo 105 (you can look up the details). In short, the bank took steps to reduce the amount of reported leverage at the times it was required to report its leverage. To regulators, and the public, the bank was purposefully presenting a distorted picture of its exposures.

Last October, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the group responsible for coming up with and monitoring worldwide bank standards, issued an unusually terse statement. Lo and behold, despite these new Basel 3 requirements including the leverage ratio:

Heightened volatility in various segments of money markets and derivatives markets around key reference dates (eg quarter-end dates) has alerted the Committee to potential regulatory arbitrage by banks. A particular concern is “window dressing”, in the form of temporary reductions of transaction volumes in key financial markets around reference dates resulting in the reporting and public disclosure of elevated leverage ratios.

Calling it “unacceptable”, the statement chastised the banking system for “undermin[ing] the intended policy objectives of the leverage ratio requirement and [the] risks [of] disrupting the operations of financial markets.” Last week, the Basel Committee finally got around to issuing new rules to make sure of compliance with their numbers-based regime.

Never once did regulators ask themselves, why now? What I mean is, authorities have made it clear they don’t condone any of this behavior, even when it falls within the letter of the rules. There’s regulatory risk in doing it, so why are banks all of a sudden taking those risks?

And it’s not like they’ve come up with some new way of doing these things. Even bank regulators can see what’s going on (and they are the last to figure it out). The banking system is basically begging for (official) trouble.

It suggests that on some level firms would rather hide their exposures from the public, meaning other market participants, and risk the wrath of the Basel Committee (and a few central bankers not impossibly blinded). Again, the question is why now? The sudden alert in October seems especially timely (landmine).

It’s also the wrong focus, as usual. Regulators care more about fealty to their numbers than they do the full range of implications of the shadow behaviors gaming them. As such, they don’t realize how everything in 2019 is upside down. If banks are slimming down for their ratios, it’s not for the same reasons as in the pre-crisis era.

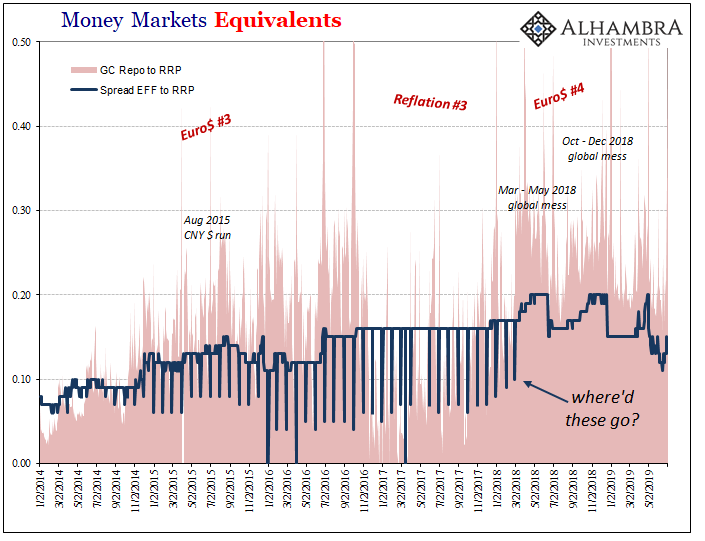

For example, it had become common practice for month-end window dressing in federal funds (above). Dealers would dump excess liquidity in this market on the last day of each month, another method for reducing reported risk exposures. The last time that happened with any size was on the last day of February 2018 (the last time it happened at all, just 1 bps, was April 30, the month-end right before May 29).

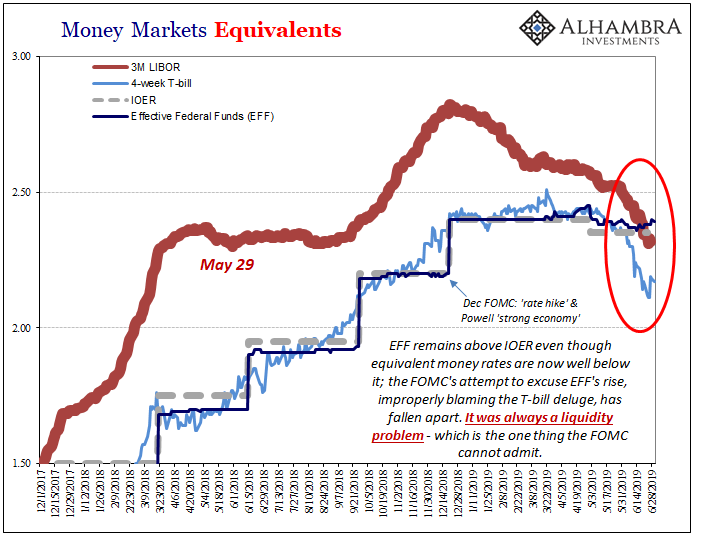

To US central bankers, it was the T-bill deluge which must’ve ended it. Faced with a federal government financing a much bigger deficit, the Treasury Department had to sell a whole lot more short-term bills which fell upon the primary dealers to first absorb. Since they have to finance what’s in inventory, no more spare liquidity federal funds even at month-ends.

Of course, that was never really what had happened; it was all a poorly constructed, haphazard lie. If liquidity was (is) drying up it had (has) nothing whatsoever to do with the fiscal deficit.

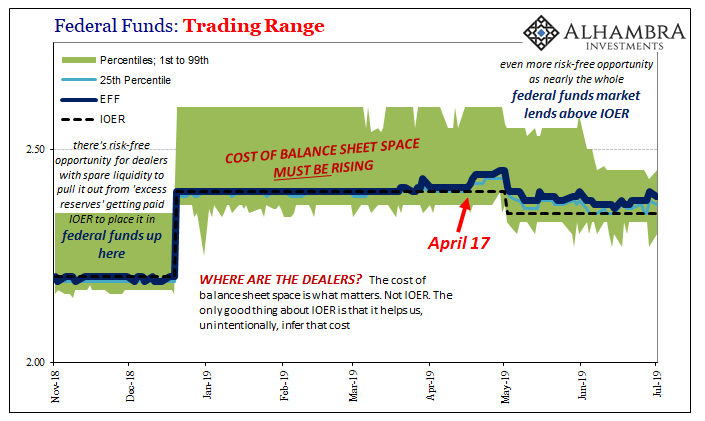

We know this because of how things have turned out on this side of the trend. At the end of June 2019, the effective federal funds rate rose 2 bps from the day before (and it only came back 1 bps yesterday). Whereas before March 2018, EFF would fall at month-end often by many basis points, it now rises even though it is already pegged above IOER.

That’s not the only thing. The repo rate jumped yesterday, too. You might notice how today is July 2, meaning yesterday wasn’t even the quarter-end. There is unusually high demand for liquidity.

What you’ll hear from the very few who follow these things is the same sort of excuses; how this is all some benign technical matter, nothing which would ever really concern you or anyone of the public. It can’t possibly be a liquidity issue let alone a systemic one because of all those bank reserves still sitting there, our central bank being just as central as always.

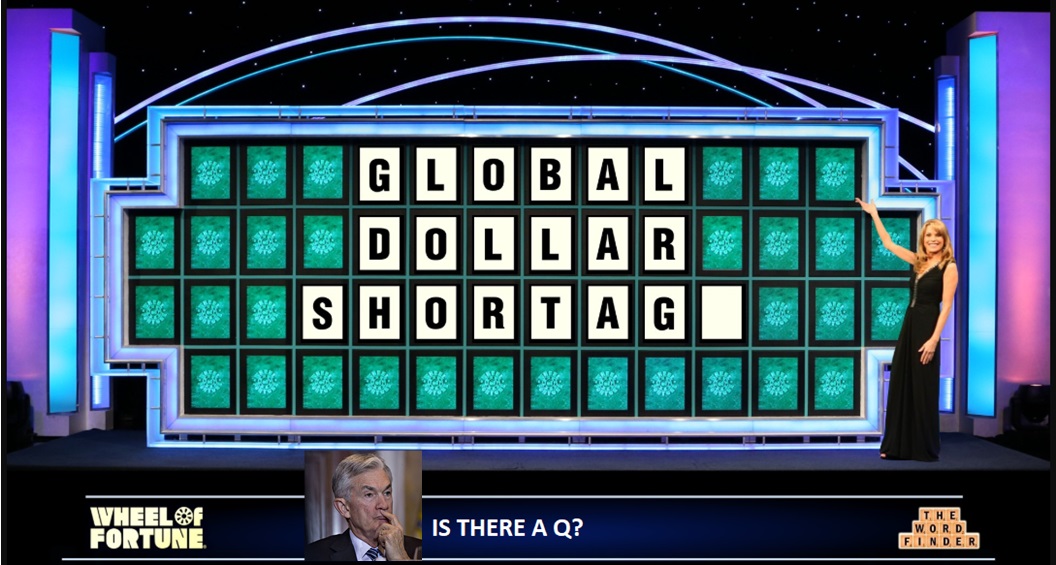

Not choosing to be so blind about the way things actually work in practice, we have the option of recognizing the one factor all the evidence keeps pointing toward. If it walks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, it’s almost certainly a duck. QE says it can’t be a duck, though, because monetary policy exterminated the species and we have to take their word for it even though no central banker has ever been asked to produce a single dead duck.

If global banks are interested in hiding more exposures from each other, federal funds window dressing is turned upside down, and the sparest of spare liquidity remains in high demand (going on three months above IOER), then it’s the very opposite of nothing to see here.

Not for nothing, something is really spooking the global bond market right at this minute (so much for the trade truce).

Stay In Touch