To most people, this inflation business seems pretty silly. There are those who argue that any inflation index whether the CPI, PCE Deflator or some other approach yet to be devised can accurately capture the concept. And they are absolutely right to question the enterprise.

Most people feel inflation in the things they do most; food, health insurance, the cost of raising children, etc. Experience doesn’t always match the government’s posted numbers. This isn’t some conspiracy, it’s the difficult maybe impossible nature of the assignment.

Monetary inflation is defined as the broad and sustained increase in consumer prices. The key word is “broad”, as in not just in certain pieces but across the entire consumer bucket. This is what led to the CPI in the first place, the attempted recreation of the experience in a hypothetical urban US consumer.

There is a false sense of precision tied to these economic accounts. We don’t know exactly what inflation is in any given month. We are only looking to gain a general sense of the situation.

Regardless of whether this is a fool’s game or not, inflation is an important aggregate tied to monetary policy. If there are sustained consumer price increases in sufficiently broad fashion, that’s something the central bank has decided is a crucial indication. In order to help do its job better, every central bank (with few exceptions) now targets a level of price increase (not a price target).

The purpose of the 2% inflation target, which was unveiled by the Federal Reserve in 2012, after years of clearly operating implicitly with that premise, is not to push the PCE Deflator to exactly that number each and every month. The word target is somewhat misleading here, quite purposefully.

Economists believe monetary policy works better (expectations management) when you and everyone else think that central bankers are scientists and engineers, precisely tuning the knobs and switches of highly sophisticated equipment to predictably hit quantitative marks (which is the very reason why QE was given its “Q”). None of that is true.

Janet Yellen at the FOMC’s January 2012 meeting, back when she was Vice Chairman of the central bank, put it rather succinctly:

MS. YELLEN. …the public will clearly understand our intention to bring inflation back to that goal over time, rather than wondering whether the committee might allow inflation to drive upward indefinitely, as occurred in the 1970s, or engage in opportunistic disinflation.

Or wondering if the central bank is effective at its central tasks. It is a check, therefore, on monetary policy. If consumer prices in the aggregate get out of hand and stay that way, then the public will know the Fed hasn’t done its job – as its own officials see it. This holds in both directions; should consumer price increases remain less than what is demanded, the public will know the Fed hasn’t done its job by its own terms.

This is why especially over the last few years the topic of inflation has taken on paramount importance; as well as why central bankers the world round keep talking it up at every opportunity. They’re nervous given how their own scorecard has been so lopsided against them.

Out of all the recent Chairman to pass through the organization, Janet Yellen was by far the best. This doesn’t mean she was good, but where she outperformed was in displaying a little more honesty than the others, Powell included. Her candor especially the closer she came to retirement became noticeable.

Yellen in November 2017, the height of inflation hysteria:

I will say I am very uncertain about this [inflation rebounding]. My colleagues and I are not certain that it is transitory, and we are monitoring inflation very closely.

That comment didn’t make the front pages at the time, of course.

Jay Powell, on the contrary, came out guns blazing. February 2018, not even a month on the job, the new Fed Chairman testified to Representative Carolyn Maloney, a Dem from NYC, that all the ingredients were present for more aggressive rate hikes. Whereas Yellen was personally cautious and noncommittal, Powell eagerly embraced the hysteria like a performer basking in the adulation of a loving audience.

He might’ve done better by taking some cues from his predecessor.

Now since then — we will submit another projection, all of us, in three weeks — but since then, what we’ve seen is incoming data that suggests that strengthening in the economy. We’ve seen continuing strength in the labor market. We’ve seen some data that will, in my case, add some confidence to my view that inflation is moving up to target. We’ve also seen continued strength around the globe, and we’ve seen fiscal policy become more stimulative.

I especially love the bit about “continued strength around the globe” as by the time he had said those words “global growth” had already become far more uncertain.

In other words, if Yellen was serious then Powell was incredibly foolish to stake his first impression with the public on yet another false dawn. Which he did. Therefore, the epic flip flop from December to early January 2019. It seems as if Jerome Powell came into office expecting to play act the role of Chairman, where someone had once told him the top Federal Reserve official needs to project confidence even at the expense of competence.

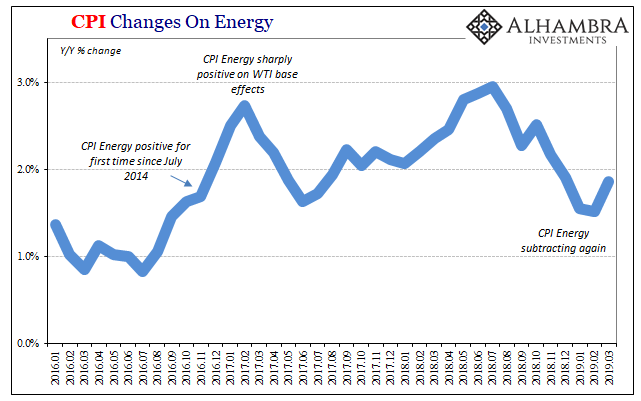

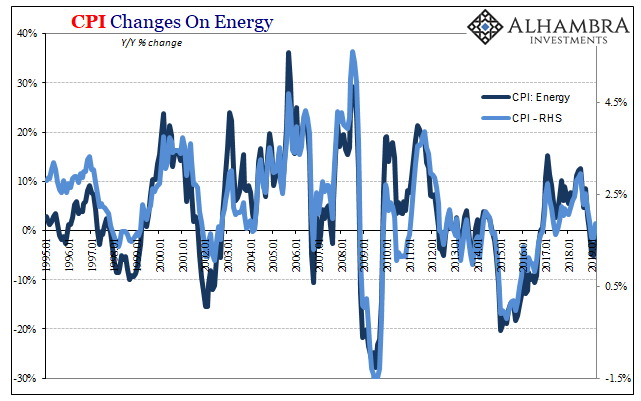

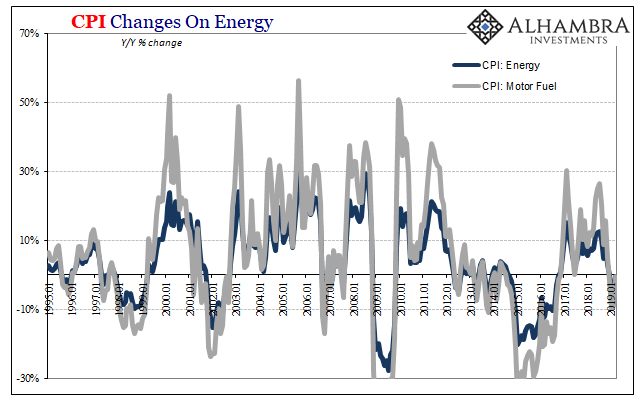

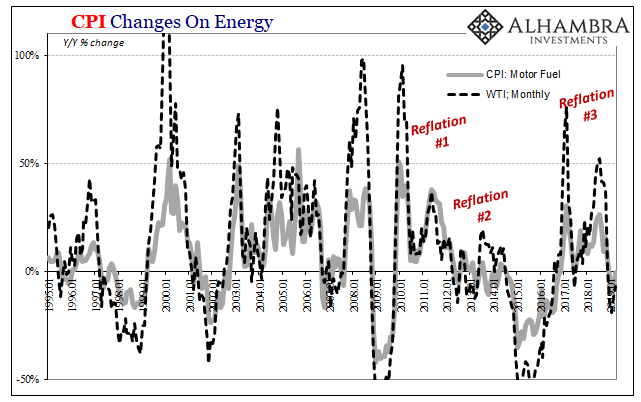

Consumer price inflation, as measured by the CPI, remains, as the new Fed policy view says, “muted.” In March 2019, the index rose just 1.86% year-over-year. That’s up from 1.52% in February, if only because oil prices were flat rather than sharply lower. Therefore, the components for motor fuel and energy overall were essentially flat, too.

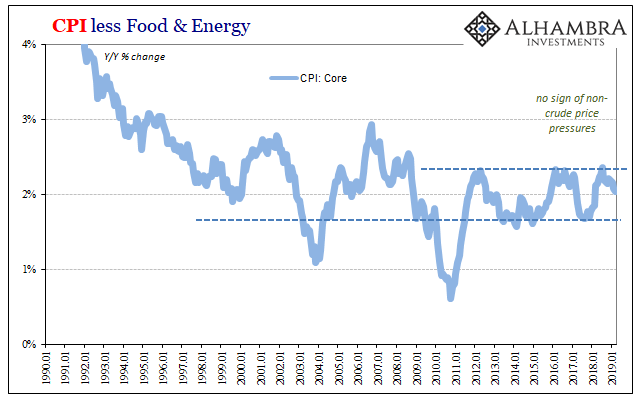

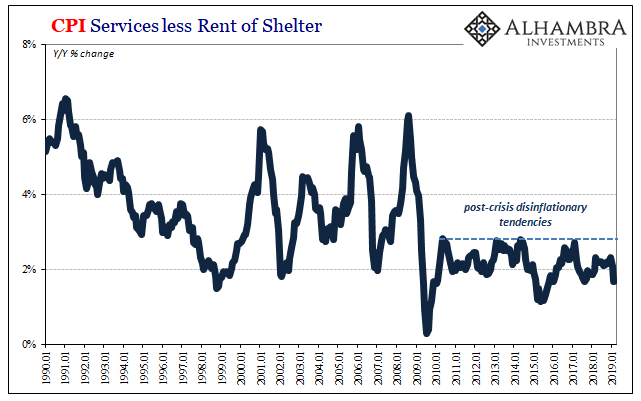

Underneath, there remains nothing to suggest any sort of pick up in price pressures. Once more: extremely low unemployment rate means an exceptionally tight labor market which forces businesses to desperately compete for workers. That competition can only mean rapidly rising wages therefore labor costs companies will surely pass along to consumers in the form of broad-based, inflationary price increases.

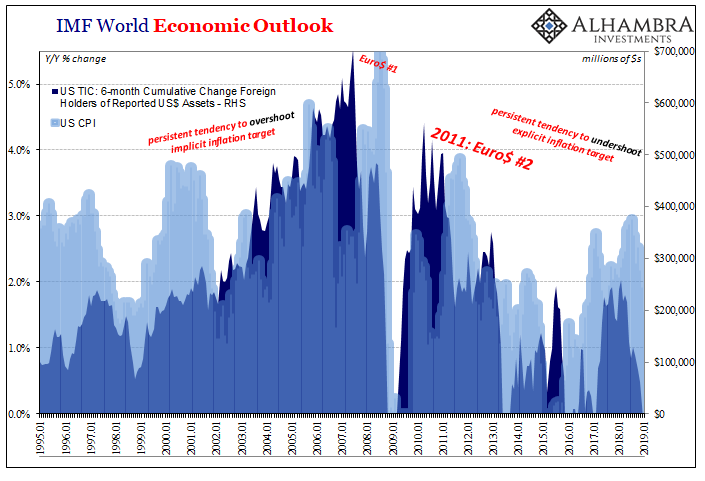

If the economy was living up to its mainstream billing, this is where it would show up. Not exactly at 2% (equivalent to about 3% CPI) but the clear tendency of the index to overshoot in far, far more months than not.

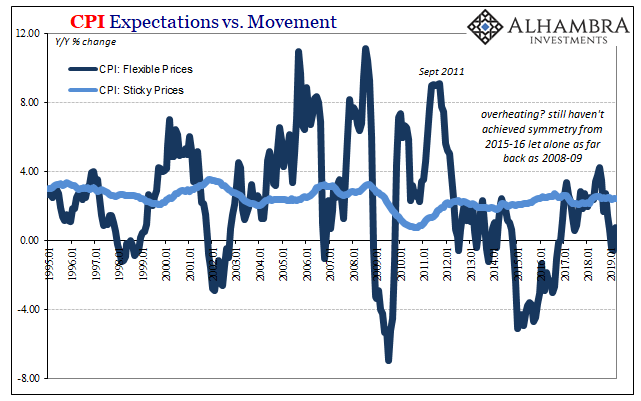

It’s just not happening. Anywhere. If anything, especially over the past four or five months, price pressures have gone the other way and not just those derived from WTI (note the trend in the “flexible” CPI, or those goods in the consumer basket where prices change more regularly if not rapidly).

This isn’t really about consumer prices. It is about doing their job, the performance of central bankers after more than a decade of very serious questions about it. If after eleven years and you still haven’t gotten it right then what are the chances you ever will? It is the only question politicians should ask of them.

Again, central bankers are nervous because they should be. They have a lot to answer for, as I wrote on this topic of money and inflation back in July 2017 just as the hysteria was getting started.

Thus, the focus on 2% inflation is important for these reasons rather than inflation itself. The failure to achieve that target in a sustainable fashion cries out that “something” isn’t right – especially after expending considerable effort, as many central banks have and still are, to ensure these outcomes money to inflation to growth (or money to growth to inflation).

Reminder: the unemployment rate has been less than the Fed’s downgraded estimates for surefire full employment for years now. Yellen was right to be cautious; they are clearly missing something big, something the unemployment rate doesn’t see, the very thing that shouldn’t be missing after four QE’s and more than ten years of “accommodative” interest rates.

When did this ongoing inflation undershoot tendency start? The year was 2012, the very year the inflation target was made public. It was also, more importantly, the year following 2011.

Stay In Touch