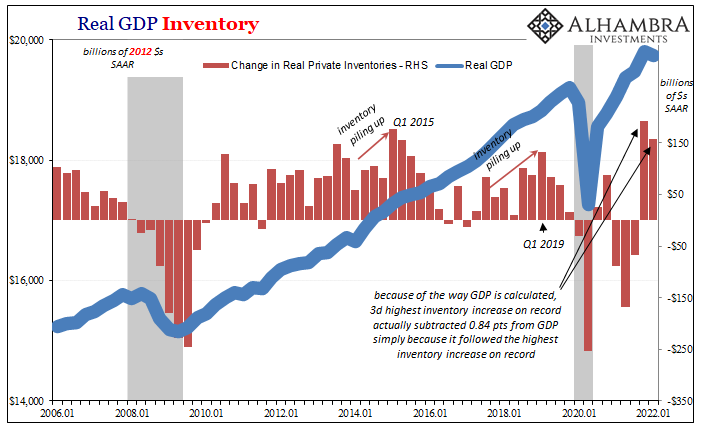

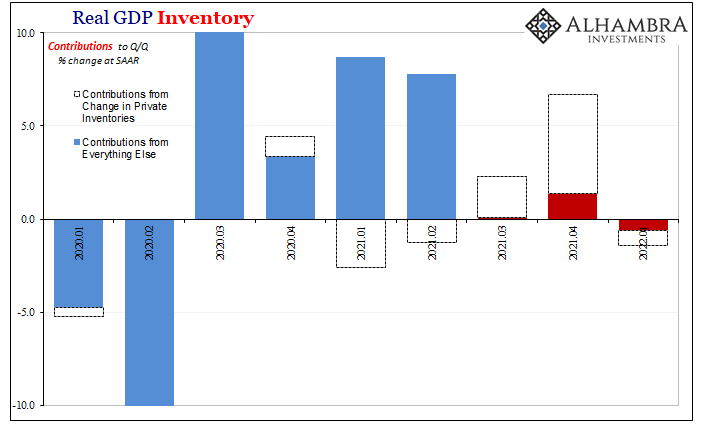

According to today’s advance estimate for first quarter 2022 US real GDP, the third highest (inflation-adjusted) inventory build on record subtracted nearly a point off the quarter-over-quarter annual rate. Yes, you read that right; deducted from growth, as in lowered it. This might seem counterintuitive since by GDP accounting inventory adds to output.

It only does so, however, via its own rate of change; the second derivative for specifically the difference. Because Q1’s third highest inventory accumulation follows Q4’s record high accumulation, the fact it was less if still huge when compared to the prior three months counts as a reduction to overall GDP.

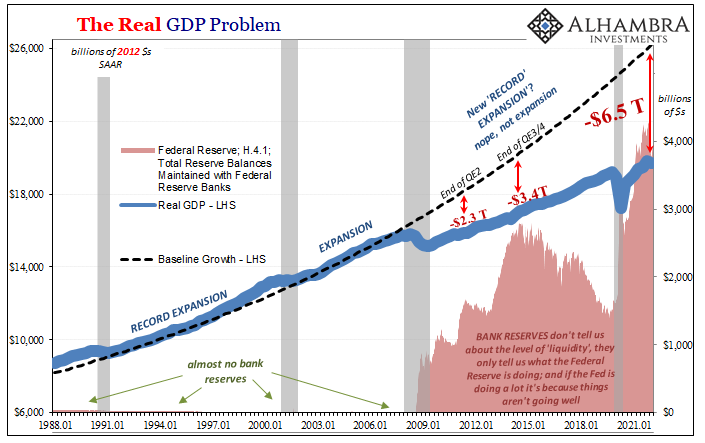

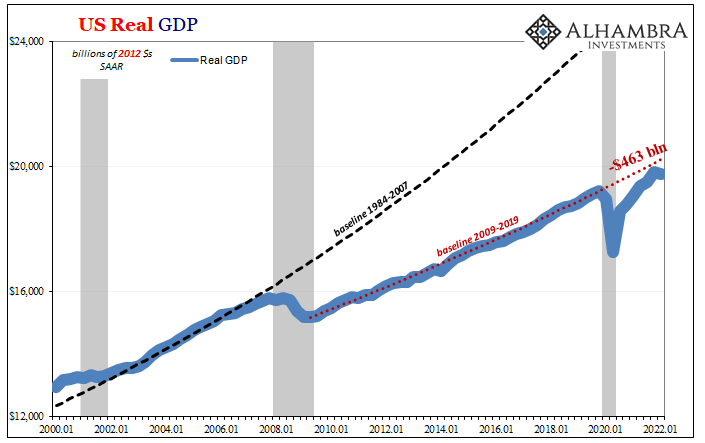

Even so, headline GDP would’ve still been less than zero because the US economy, contrary to most price illusion perceptions, has been heading toward trouble for some time.

No matter the numbers and the way the BEA calculates individual items, inventory or not the situation didn’t change during the first quarter. If anything, the current release simply confirms the fact that the flow of goods is not all price illusion (as discussed yesterday; the BEA largely confirming my unscientific deflation of Census’ nominal figures).

This is three problems wrapped into a single enigma we have to still call “inflation.”

First of all, so long as American businesses keep ordering more goods even if they end up as unsold inventory, consumer prices will remain painfully “robust.”

Producers don’t care one bit where their products end up or how they might get wherever they go. For their part they’ve made a sale and if domestic wholesalers and retailers continue to press for more product at a time when supply and transportation problems/costs remain high, these will remain high.

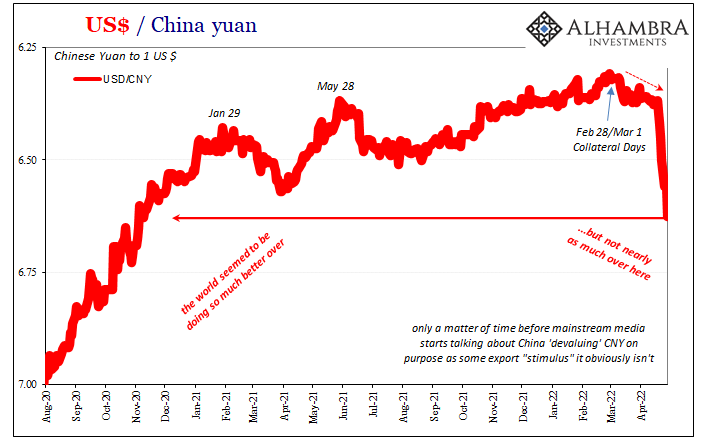

The supply shock is still shocking, particularly considering where most of this stuff is being made (more on this in a moment).

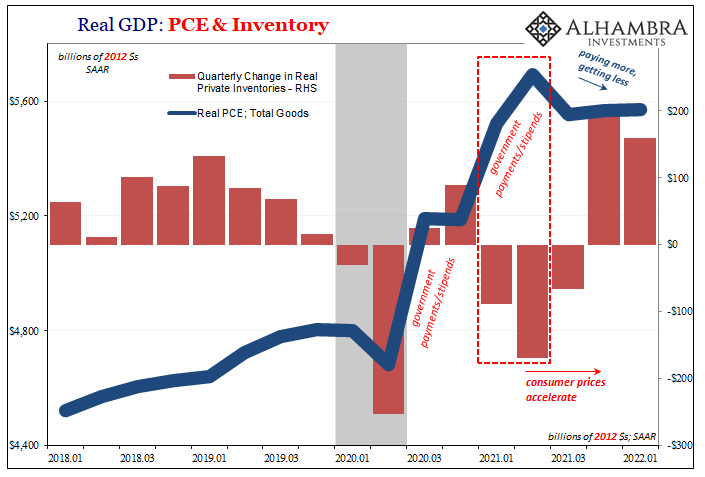

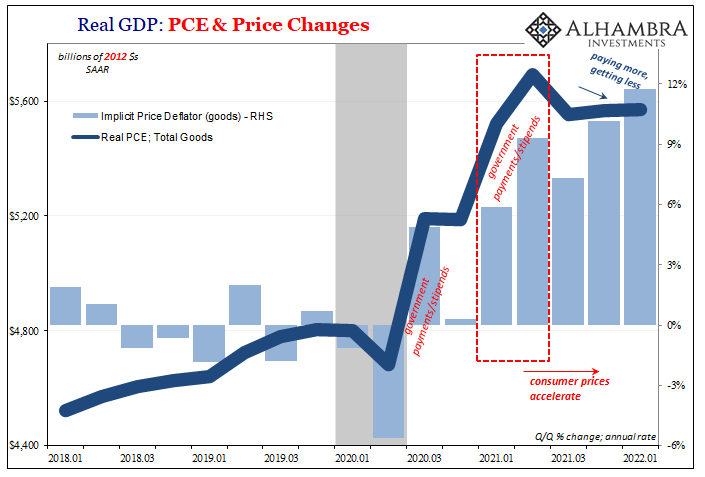

Naturally, the goods deflator was huge(r) even as actual consumer demand was not (more on this, too, in a moment). At an annual rate of 11.8% q/q for the PCE Goods deflator, this is where most of the “inflation” came from.

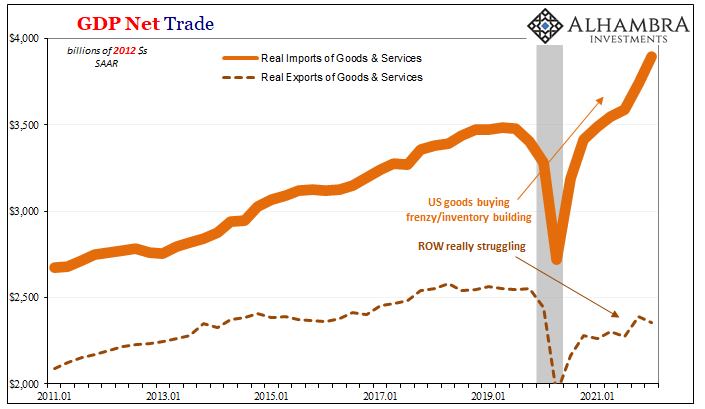

And most of the goods being stuffed into inventories is coming from elsewhere around the world. This is the second reason of and for “inflation.” The post-Uncle Sam frenzy has benefited foreign producers even more than consumer demand had prior to 2020.

As a direct consequence, US imports of goods have absolutely exploded – even if a lot of those foreign goods didn’t get sold to consumers straight away. In GDP calculations, imports were up nearly 18% q/q (annual rate) for the second straight quarter (while exports fell) aligned with those record and near record inventories.

At least a deduction here (-3.2 pts from topline GDP) makes intuitive sense given that this saturation of goods has largely benefited those outside of the BEA’s coverage area.

This leaves the goods economy facing its third potential problem with regard to so much buildup; questioning a further “what if” as it relates to softening sales. This is always, everywhere the danger when inventory begins to truly outpace everything else, and since the US and global economy (by virtue of making and shipping products to the US) has been utterly dependent on this segment for whatever of a rebound (not recovery) the whole thing is highly susceptible to any reverse (or even just less of an increase).

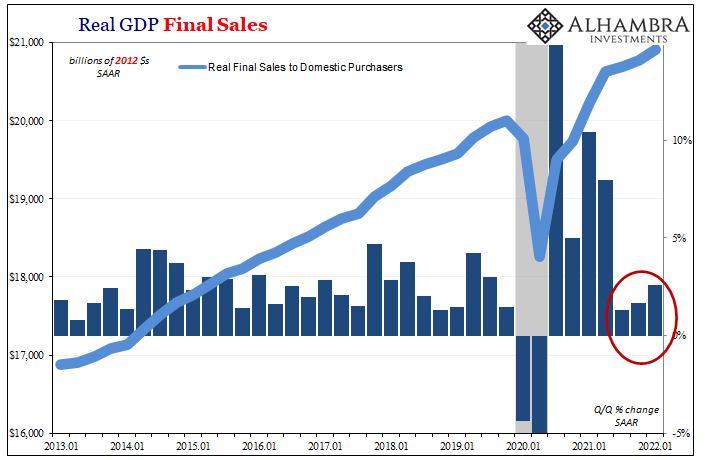

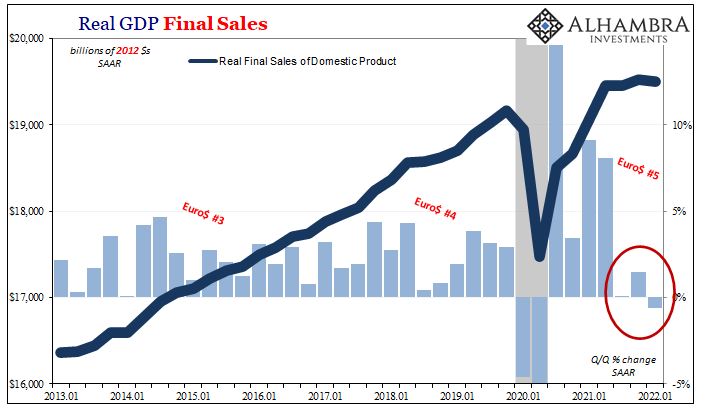

That along with what you see below are the two major takeaways from the GDP report. It’s not really about the “unexpected” minus sign, the overall -1.42%, rather how such weakness beyond inventory has been there for now spanning three-quarters of a year.

Q4’s record inventory build had obscured that fact from the headline. By count of both sides of “final sales”, this economy has been sputtering since around the middle of last year (where have we heard that before?).

Real Final Sales to Domestic Purchasers, the BEA’s account of all goods and services bought by anyone in the US, consumer or business, only gained 2.6% q/q (SAAR) after two straight quarters less than 2%; two point six would’ve been a weak quarter before 2020, let alone with so many goods being imported with no signs of it stopping soon.

Because so much of what was bought (and put into inventory) at the margins came from those outside sources, Real Final Sales of Domestic Product, everything which was made or served by Americans and American businesses sold to anyone anywhere, also dropped like the headline in Q1, underscoring just how much all that stuff shown above really is propping up the public’s visualized sense of the overall economic situation.

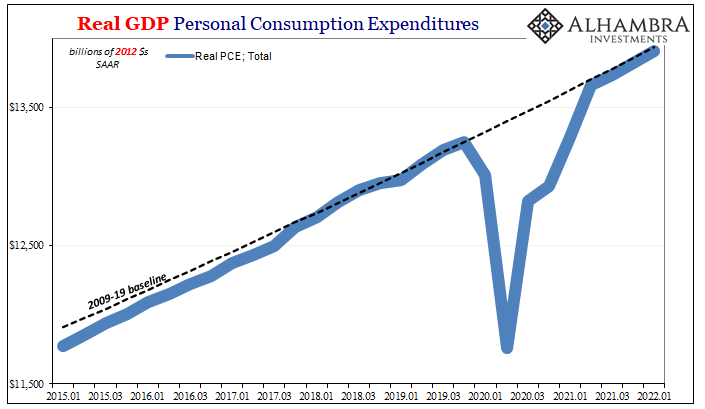

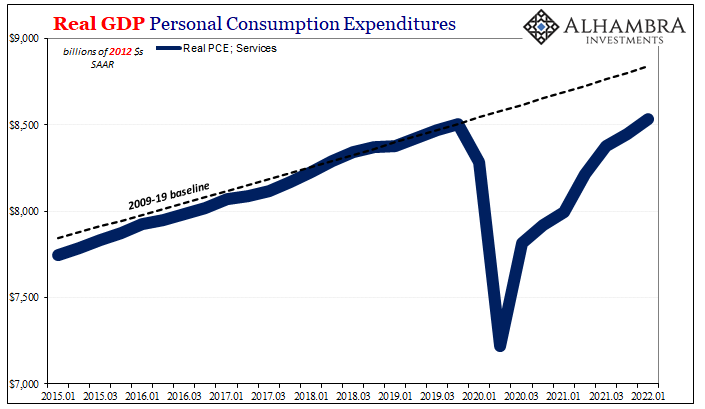

As has been the case since the last recession, spending on goods may be up though spending on services is not. Therefore, combined, consumer spending adjusted for prices (and seasonality) is barely keeping up with the pre-2020 trend. This lackluster outcome the clear result of Americans having to pay more for goods in order to get fewer of them, leaving them unable to complete the services recovery.

Even the nominal economy seems to have turned a corner. The BEA believes that nominal GDP increased by 6.5% q/q (SAAR), the lowest since the contraction. For reference, there were better nominal rates during “globally synchronized growth.” In Q4 2021, the rate was 14.5%.

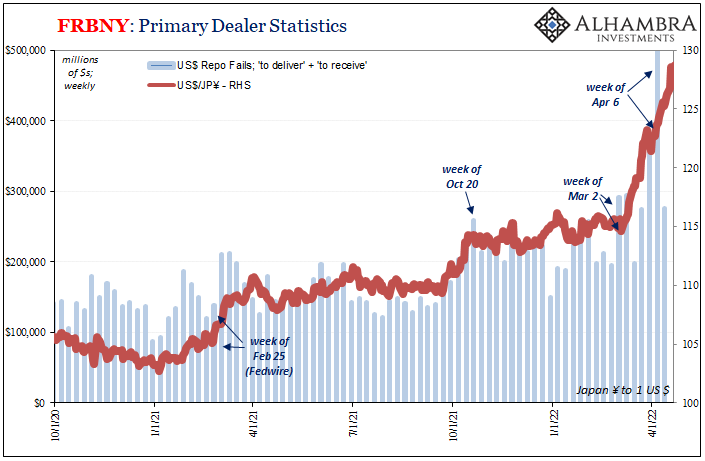

Everything apart from the focus on goods and goods prices has been trending in the wrong direction for quite some time – just as market indications pointing to Euro$ #5 have been advising since last May.

Does this mean the US economy, at least, has already tripped into recession as the yield curve and others have been warning?

There are no definitive indications to that effect, and several including business investment (which rebounded in Q1) which would go down in the other column.

However, the broad-based weakness especially what is illustrated by both sets of Final Sales numbers do confirm that serious economic problems aren’t going away. Combined with a potential nominal slowdown and, yes, all that inventory, each consistent with prerequisite conditions for a possible contraction.

Frankly, the chances of a recession aren’t what we see in the current figures, rather the current figures are consistent with a recession trajectory and trend long since plotted out by the marketplace. These don’t prove one has arrived, yet do add a lot more to the confidence and chances one could.

Continuously weak economy riddled with imbalances and inconsistencies, yep. I mean, really, these are the results you’d expect to see from a system at the very least moving in the direction of a serious contraction.

Is the only thing left a possible shock to tip it over conclusively? Assuming, of course, one hasn’t already happened in between Q1 and Q2.

Stay In Touch