Give stimulus a chance, that’s the theme being set up for this week. After relentless buying across global bond markets distorting curves, upsetting politicians and the public alike, central bankers have responded en masse. There were more rate cuts around the world in August than there had been at any point since 2009.

And there’s more to come. As Bloomberg reported late last week:

Over the next 12 months, interest-rate swap markets have priced in around 58 more rate cuts, assuming central banks maintain their current trajectories in easing. Those cuts could total another 16% in global reductions.

This week, the ECB is almost certain to join the ranks. Not just some interest rate adjustments, either, with short-term rates there already negative, very likely a restarted perhaps modified QE. Would anyone be surprised if European monetary officials did those things while at the same time pre-announcing an expanded list of eligible assets?

It has become convention (but not wisdom) that central banks must shock markets. At this point that would mean something like a hint from Mario Draghi that his successor Christine Lagarde is thinking about buying equities this time around and not just various debt products (implicitly acknowledging that buying up so many credit instruments last time around didn’t quite lead to the desired effect).

Pure overkill, many say. Things aren’t really that bad, are they?

While “stimulus” is being ramped up this summer, it hasn’t been entirely new. Starting in China, for example, the PBOC and government authorities have supposedly been prodding and nudging the reluctant Chinese economy for quite some time. Only, it doesn’t appear as if China’s economy is accepting of the invitation.

It’s not working.

The latest figures from the Chinese General Administration of Customs demonstrate the sheer stubbornness of the problem. Reporting estimates for exports and imports, it is the latter which is suffering the most rather than the other way around as anyone imagining “trade wars” as the primary cause might expect.

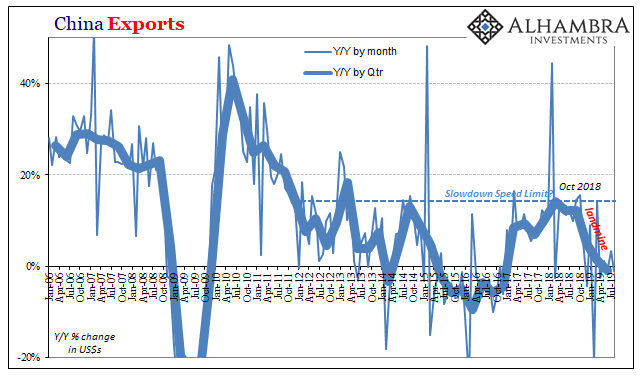

Exports out of China fell by 1% year-over-year in August 2019 after rising by almost 10% in August 2018 (from August 2017). That means the external focus remains pretty much the same – it’s not nearly enough activity to propel the country’s vast industrial sector forward. Anything less than 20% growth, sustained, is a major economic drag.

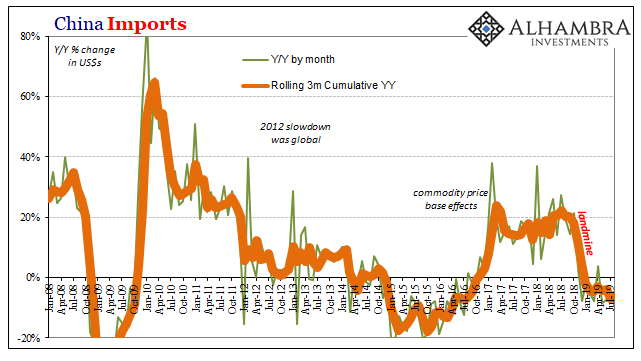

But if the Chinese are experiencing tough luck upon global markets, they’re at the same time subtracting even more by what should be coming back in – or not. Imports contracted again last month, down 5.6% year-over-year. It was the fourth straight month of declines, and the eighth time in the last nine months (going back to the landmine).

If China really needs something like 20% export growth to fuel and steady its economic arrangements, the rest of the world downstream in the supply chain really needs something like 30% growth in raw materials and basic goods heading into the country. It’s an even bigger gap to what might be reasonably characterized as a healthy situation for internal China.

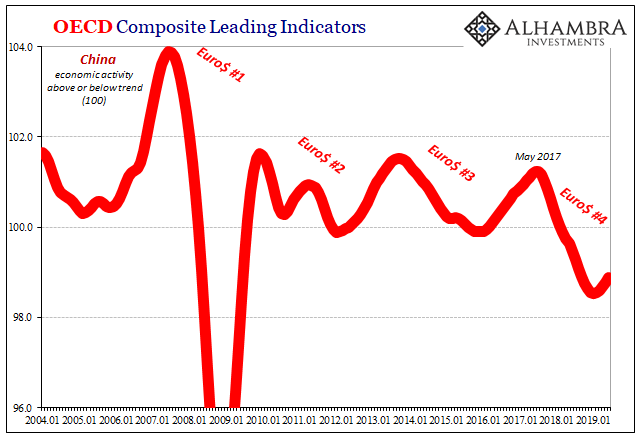

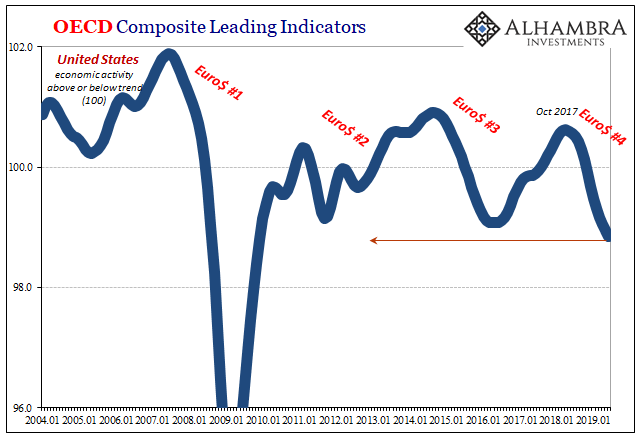

By many various measures and estimates, this is only beginning. The OECD, for example, its index of Composite Leading Indicators puts China in unfamiliar territory – we haven’t seen a worse forward-looking situation since the global Great “Recession.”

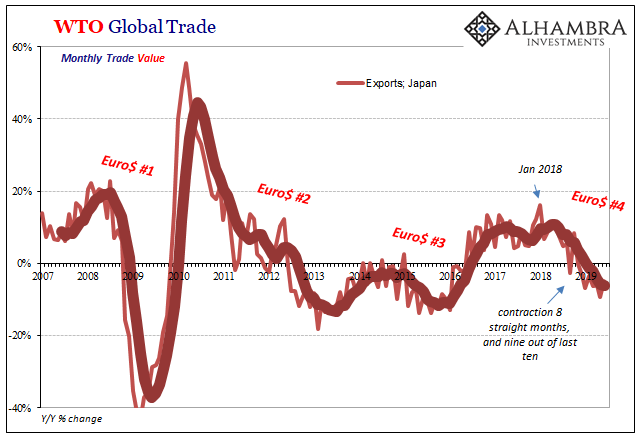

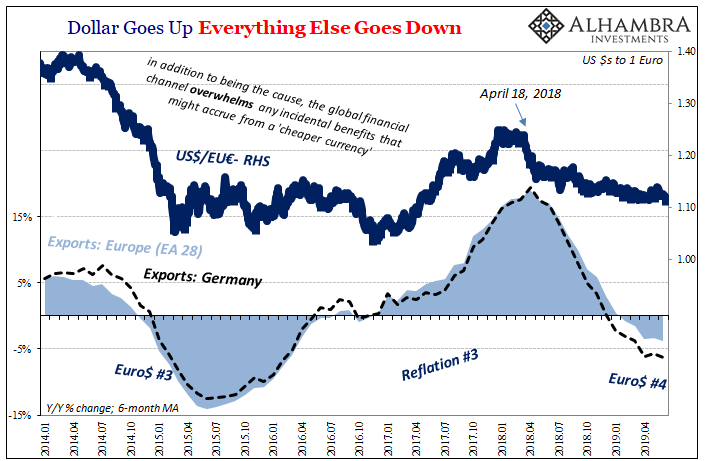

All of which means, again, “stimulus” isn’t working. And China’s economic struggles are far from their own. That doesn’t mean trade wars; rather, it shows up as broad-based global weakness that has entered largely through the trade channel (making it easy to think tariffs and geopolitics). It both predates trade wars and, more importantly, is not the first instance of this kind of economic erosion.

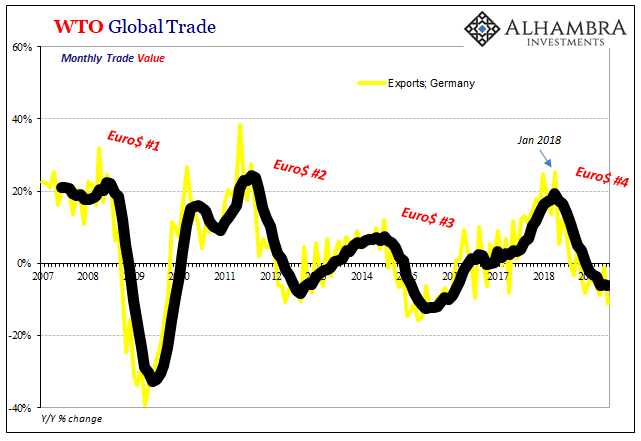

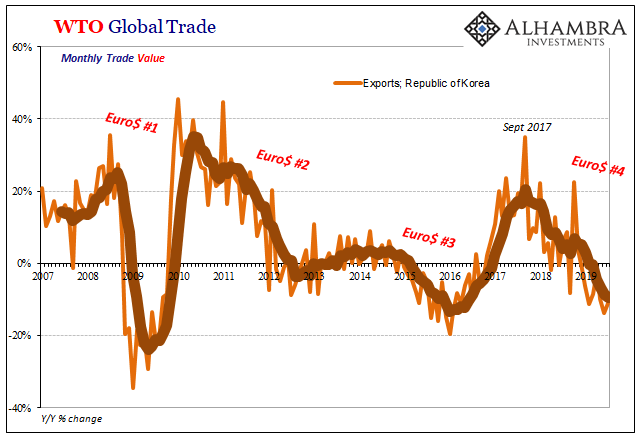

It is instead the fourth over the last dozen years. The pattern is exactly the same everywhere you look – because by the eurodollar system the global economy really is a global economy. There aren’t distinct pieces or national systems operating as an island, as Jay Powell would have you believe of the US, there are only variations surrounding an independent baseline set in motion, and stubbornly maintained in direction, by that far-reaching monetary system.

Everywhere you look, a nastier Euro$ #4 (especially the rate of change – falling faster). Both in terms of where things are in the process and more so all these numbers (including bond markets) digesting the probabilities of where things will go from here. How far is the downside, so to speak.

The world right now looks way too much like Euro$ #3 already, with no end in sight and likely significantly more of it to come.

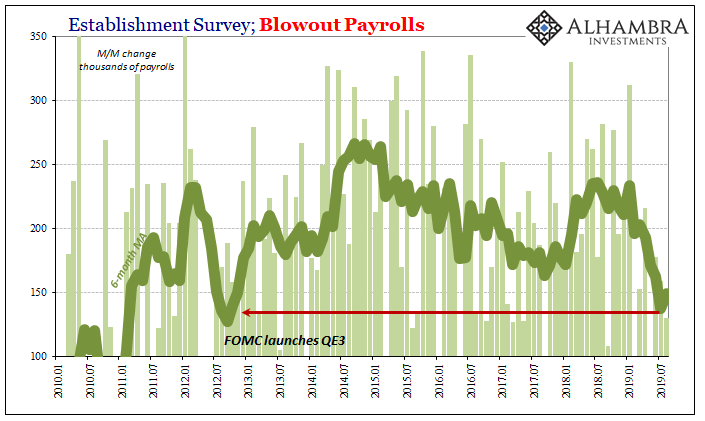

And that is exactly why so many rate cuts in 2019 only a little more than halfway through when this year was supposed to have been the parade, the global synchronized celebration of globally synchronized growth. Central bankers all over aren’t yet panicking, the ECB may be the closest because Europe like China is at the front of the line this time around, but by their actions they are far, far less confident than they are required to appear in public.

With good reason.

Like Jay Powell said last week in Switzerland; we need rate cuts though we really don’t need rate cuts. Ridiculous, I know, but it’s not what they say, it is what they do.

Stay In Touch