Since I don’t speak Japanese, I’m left to wonder if there is an intent to embellish the translation. Whoever is responsible for writing in English what is written by the Bank of Japan in Japanese, they are at times surely seeking out attention. However its monetary policy may be described in the original language, for us it has become so very clownish.

At the end of last July, BoJ’s governing body made a split decision. By a vote of 7 to 2, the central bank adjusted its bond buying policy. The change was something subtle, but it caused a good deal of consternation simply because the Bank of Japan has bought up everything under the sun.

In English, the word that gave so many people pause was flexible; as in, “the bank will conduct purchases in a flexible manner.” The same clause in the official statement reiterated BoJ’s commitment to holding the 10-year JGB yield around zero. However, bond prices weren’t going to be pegged, “yields may move upward and downward to some extent mainly depending on developments in economic activity and prices.”

The statement unleashed a wave of JGB selling. The media took it and ran with it, shrieking about the same global mantra, interest rates have nowhere to go but up. If Japan of all places had finally arrived at the conclusion of monetary stimulus, and “flexible” seemed a possible first step toward an exit, then Powell, Draghi, and the rest of them were surely right about globally synchronized growth.

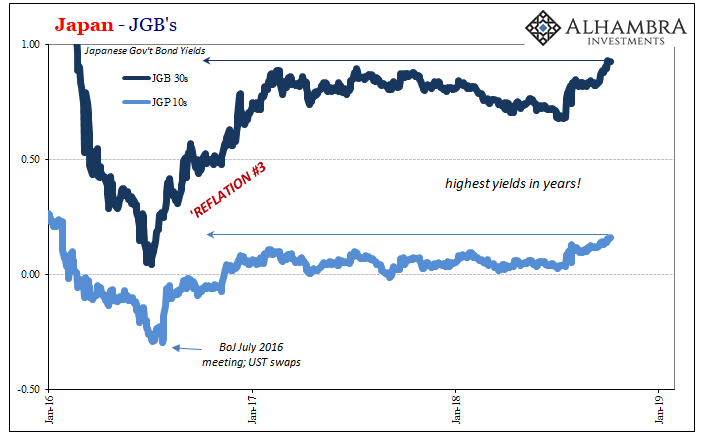

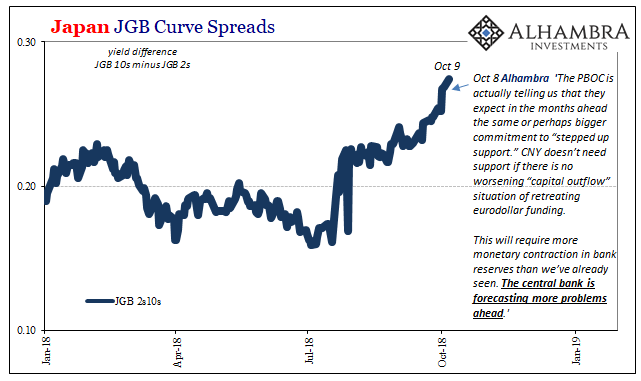

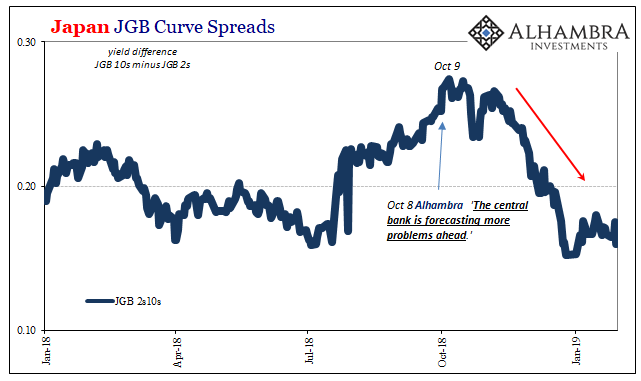

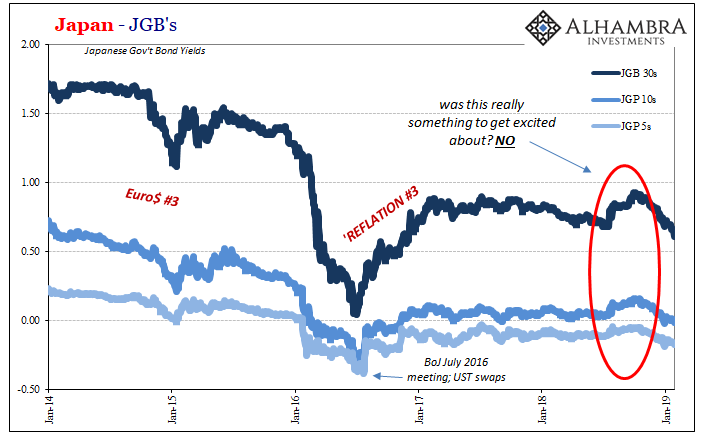

This was just in time, too. August and September 2018 were replete with contrary warnings. Following from the worldwide collateral call on May 29, what was left of globally synchronized growth needed something of substance upon which to pin any lingering hope. By early October, JGB yields had pushed to the highest in years. The JGB curve, steeper.

Japan would be a big one indeed.

Or, it would have been. It didn’t quite turn out the way everyone had hoped. This last JGB freakout was nothing more than the same hype and hysteria. Yes, nominal yields rose, but they didn’t really change all that much. The sensationalism surrounding the global recovery narrative had reached such a pitch that it blocked out what may have been left of rational thinking.

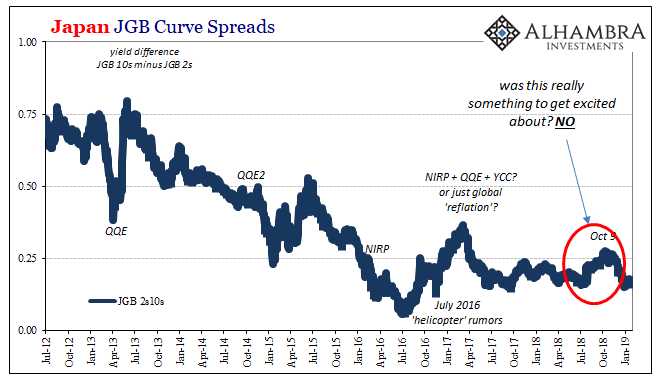

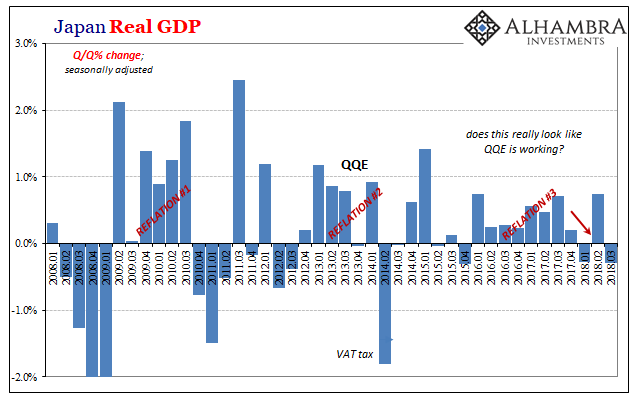

In honest inquiry, it was difficult to be anything other than unimpressed. Japan was supposed to be finally at the doorstep of recovery and this was it? The 2s10s steepened by about 10 bps. Ten. It looks like something big on the chart above, and then almost nothing on the chart below. Guess which view ended up meaning anything.

But that’s how everything is framed, a purposefully disingenuous emphasis on only the most charitable view. Markets never move in a straight line, which means that they are eventually going to move in the “right” direction. That doesn’t necessarily mean that the market, any market has readily and fully embraced the mainline interpretations of that direction.

It is after so much time a fit of desperation. After all, the title of BoJ’s July 31’s announcement gives away the game. On almost every other occasion, in English it is your typical bureaucratic boring, Statement on Monetary Policy. Simple. Direct.

For that statement last July, though, the BoJ quite purposefully called it something else, Strengthening the Framework for Continuous Powerful Monetary Easing.

Powerful Monetary Easing.

If you have to say it, in every likelihood it isn’t. That would have been true in April 2013 when QQE was introduced, and it is especially true half a decade later after several more modifications to it. To feel compelled to repeat Powerful Monetary Easing after all this time, and then to hysterically hype the smallest yield changes as if evidence for the claim, it really is a circus. A pretty obvious one.

This is the inherent contradiction of an expectations-based policy regime. There is no money in monetary policy, but central bankers want you to think that there is a lot. In Japan, however, they’ve quite unintentionally shown their hand. After more than half a quadrillion in assets, JGB yields barely budged and are now back negative (10s and closer) again in 2019.

Powerful Monetary Easing.

BoJ officials as their counterparts in America (rate hikes) and Europe (end of QE) hoped that by engaging in a small sleight of hand (flexible) you would have been mesmerized by the potential for policy change and then infer something grand from it. Recovery in Japan at last, a truly great feat.

In believing this, you would forget all about that “other” stuff, not just May 29 globally but in Japan specifically disappointing inflation and the reappearance of minus signs in major economic accounts. The Bank of Japan really believes this is it, so don’t believe your lying eyes follow Mr. Kuroda blindly!

Rather than enhance credibility there is something really pathetic about this Powerful Monetary Easing, or however it might be written in Japanese. The economic and market moves consistent with the idea become smaller and smaller and smaller the longer this powerful easing continues. The tiny bump in JGB’s, as UST’s and German bunds, this last time was so minor that it actually contradicted the very notion, proving beyond doubt there has been no power, no money, and therefore no easing.

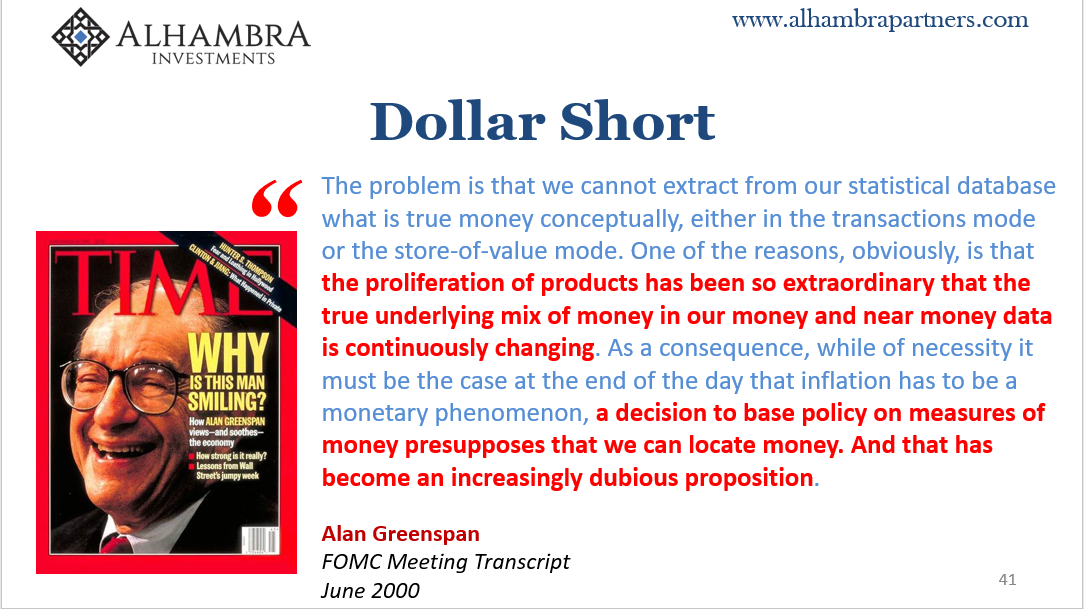

The thing people have the most trouble with is the idea that central banks are not central. It flies in the face of everything you have been taught and told your whole life. The media still gives these guys every benefit of every doubt, and central bankers (ab)use that privileged platform to perpetuate their myth. If you can’t define money, fake it.

The clowns write Powerful Monetary Easing and Economists parrot the line in the mainstream media who writes it up as if that’s what is going on despite every bit of evidence to the contrary. This is the real “power” behind expectations policy, the smoke and mirrors of unquestioned pedigree. Unfortunately, what the world actually requires to achieve economic recovery is real monetary competence; Japan most of all.

Get some of that, then and only then will yields around the planet skyrocket. No translations will be required.

Stay In Touch