There’s always weakness even in the most booming of economies. Even in the real booms, not the 2017 hysteria kind, not all cylinders will be firing. What makes them real, however, is when the vast majority are. The concept behind globally synchronized growth was a valid one, it just never came out in practice.

The impression has been incorporated into various data points over the years. These are quantitative measures designed to relay information about this idea of broadness. If so many pieces are in lockstep one way or another, then that’s probably something worth paying attention to and investigating.

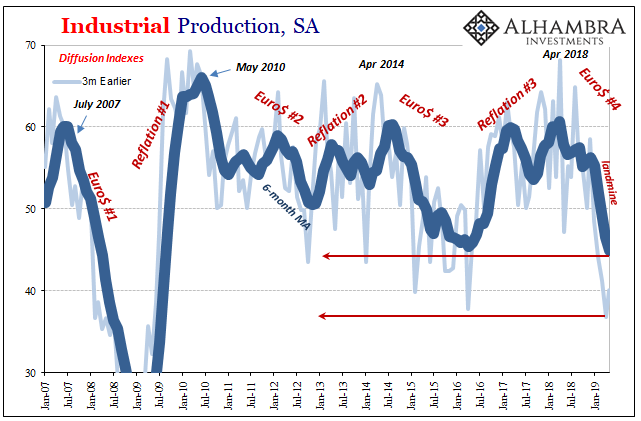

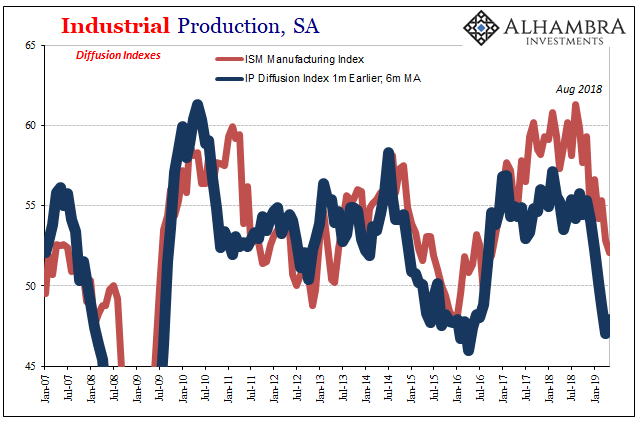

The Federal Reserve’s Industrial Production (IP) statistics include several of these. They are diffusion indices, though a bit different than the sentiment surveys (also diffusion indices) you typically find. What’s being measured here is not how purchasing managers feel their order flow has changed, rather it’s how many individual data components within the whole are positive or negative in any given month.

It is intended to screen out any cases where one large, concentrated positive or negative may skew the data for the wider industrial system. The theory remains the same: if a lot of things are growing, it is consistent at least with the idea of broad growth and the positive interpretations that go along with it.

Conversely…

The updated data for May 2019 (the diffusion estimates are one month behind the rest of the IP numbers) suggest something big is brewing. At both the 3-month and 6-month intervals (that is, comparing data series for the latest month’s index values against those from 3 and 6 months ago) what we are seeing is the kind of broad-based contraction not found since 2009. These two diffusion indices (the 6-month looks pretty much the same as the 3-month, shown above) have plunged since, nor surprise, the landmine.

Both of these are now stuck in the 30s, obviously a level you don’t want to see on any diffusion no matter how it is constructed. This has brought the averages down below where they were even at the bottom of Euro$ #3’s “manufacturing recession.” It’s another instance indicating that even though Euro$ #4 seems to be just getting started it might already present much bigger challenges to the global economy.

The US very much included.

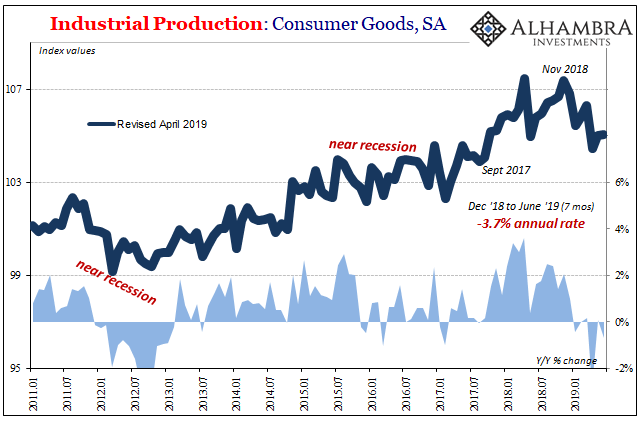

Though the growing contraction is broad-based by measure of the diffusion indices, its center is in the segment producing consumer goods (another contraction in June 2019). That’s obviously a bad sign because, consistent with the continuing awful retail sales estimates, this suggests that the unemployment rate isn’t actually relevant and therefore can’t be the baseline view for a second half rebound.

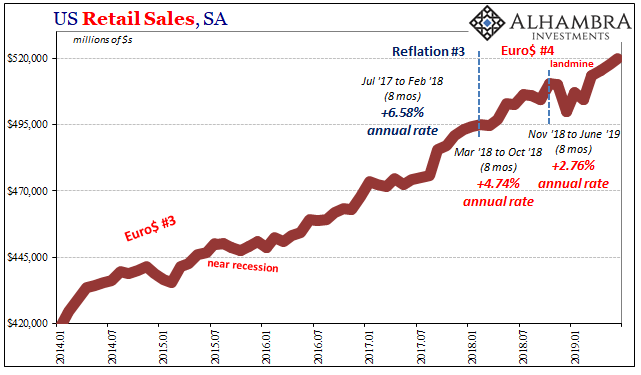

There’s also consistency in how it came to be this way. Just like retail sales, we can easily divide up the different stages: from “boom” to the first part of Euro$ #4 to post-landmine.

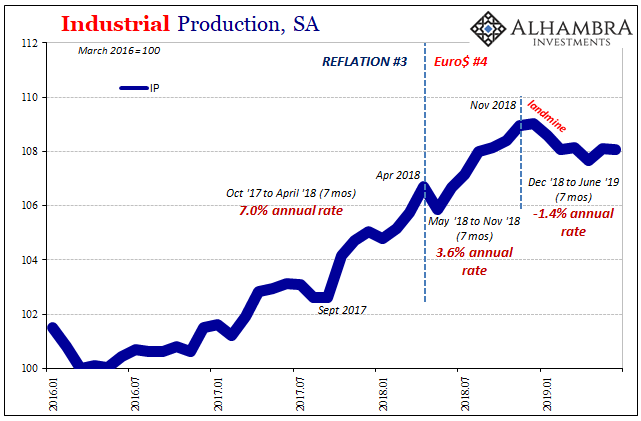

Immediately following Hurricane Harvey in 2017, IP accelerated to an annual growth rate of 7%. It then slowed down to less than 4% in those crucial middle months of 2018. While the hawks were sharpening their rate hike talons, it was already a lost cause. Following last November, overall US industrial production is now falling at a 1.4% annual rate.

It rejects the notion that if the economy doesn’t collapse tomorrow the less danger there is of more serious declines. Instead, each month the progression continues this way, the greater the chance its ultimate depths are that low (something like a full-scale recession).

When you see minus signs and further that those minuses are the product of broad-based weakness spanning well over a year, a second half rebound shouldn’t be the first thing which springs to mind.

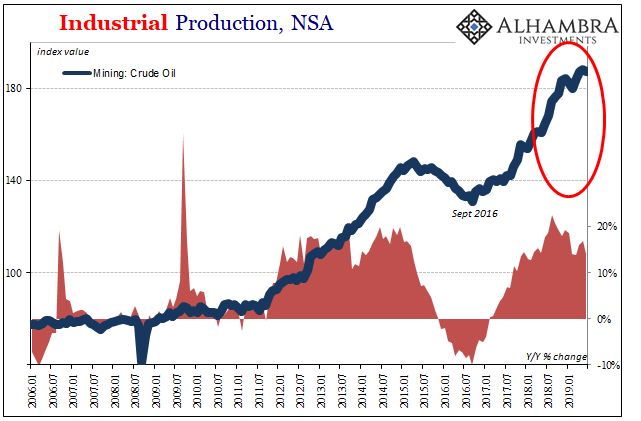

For much of the past several years, it had been a contest between oil extraction and motor vehicle production. In other words, at the one end, the boom end there was an actual boom in the vast shale plays. The mining sector devoted to pumping crude has been the one exceptional piece of an otherwise lackluster economy.

That’s why the diffusion indices attached to IP never got nearly as high and optimistic as other sentiment-based surveys (especially the ISM).

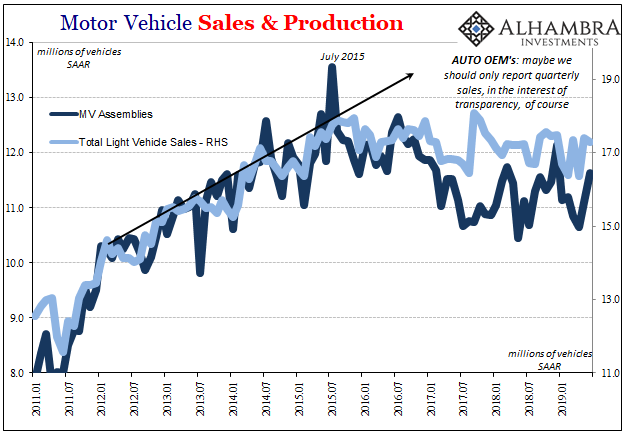

On the other side, Motor Vehicle Assemblies (MVA), the Fed’s proxy for domestic automobile production, have slowly churned lower and lower. Auto sales have languished (what boom?) since Euro$ #3, and as inventories built up in between production volumes have been forced to adjust.

With IP in general contracting despite oil, or despite cars, for that matter, it’s no longer an either/or situation. We don’t have to wonder if a narrower advance predicated almost exclusively on the oil patch can actually produce a widespread boom because it is almost certainly too late.

Indeed, it seems to have been that middle frame when everything really turned the wrong way. If ever there was a chance for an inflationary breakout, it was early to mid-2018. All it needed was what I wrote last July:

At some point, the boom had to have boomed. We are moving into the past tense for all this now, inflation hysteria almost certainly tucked away into the economic ledger alongside four other false dawns. Data is coming in for June 2018, meaning half of this year already recorded and analyzed. It’s not what it was supposed to have been.

The economy had already slowed by then, confirming things were heading in the other direction – just not all at once. There was never really enough broad-based strength and, according to the bond market, way too much righteous pessimism not about trade wars (or whatever other excuses had been offered in the early months of 2018) but dollar shortage risks (confirmed on and after May 29).

The global economy was synchronized the whole time – no decoupling. It just wasn’t growth.

A year later, it leaves us to ponder the hopes for a second half rebound based on a long-entrenched trend and progression continuously moving in the wrong direction. Rather than dissipate into “transitory” factors, it is picking up momentum and adding more pieces to the downturn.

Though many now seem to be relieved how through the first half of 2019 neither the US nor the global economy has collapsed, and therefore take it as a sign it will get back to the plus side very soon, it is actually the downside risk which is gaining. There is more evidence with each passing month for how Euro$ #4 is shaping up to be more severe than Euro#3 or Euro$ #2.

Stay In Touch