Najib Tun Razak was elected as Malaysia’s Prime Minister in early 2009. Taking office that April amid global turmoil and chaos, Najib’s first official visit was to Beijing in early June. His father, also Malaysia’s Prime Minister, had been the first among Asian nations to open formal diplomatic relations with China thirty-five years before. Celebrating the milestone might’ve been the proposed purpose behind the state call, but that’s not what anyone was talking about.

The invitation was extended at the behest of the Chinese Premier, Wen Jiabao. At the top of their agenda, besides the official festivities, was a bilateral trade agreement. China and Malaysia were going to conduct trade bypassing the US dollar. The Wall Street Journal reported:

China has been promoting the idea of replacing the dollar as the global currency, suggesting that a basket of currencies less linked to the fate of one economy would make more sense. It also has been talking about using the yuan for trade settlements, starting gradually in the region and then expanding farther abroad.

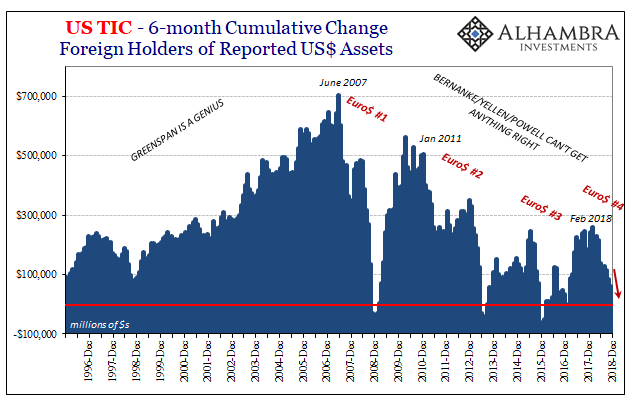

Malaysia was equally as eager, small wonder given the nature of the times. Should we be surprised that a worldwide dollar shortage, which is all that the Great Financial Crisis had been, provokes a search for alternates? Given how the US and Europe had been the epicenter of the monetary earthquake, Asia only experiencing what seemed collateral damage, hitching fortunes to the unbreakable Chinese growth engine appeared downright prudent.

It was Wen who laid out China’s first rationale for this line of thinking during the absolute depths of the panic. In March 2009, the country’s number two said they were concerned about US stimulus. Seriously. “We have lent a huge amount of money to the U.S. Of course we are concerned about the safety of our assets. To be honest, I am definitely a little worried.”

The US was going to be printing money to get out of the monetary event and that wasn’t the action of a good partner, let alone the central pillar of the global dynamic. If only.

Fast forward a full decade. Where’s the yuan? They’ve had all this time and not even China’s authorities are taking the steps required to make it a functional global currency replacement. If they could have, they would have long before 2019.

This is not to gloat; not at all! Rather, it exemplifies very well the big predicament. Not just the one plaguing China but what’s the perpetual anchor upon the whole world. We are all gripped by what amounts to collective insanity, stuck with something that clearly doesn’t work without any serious recognition, let alone commitment, to do anything about it. All of us.

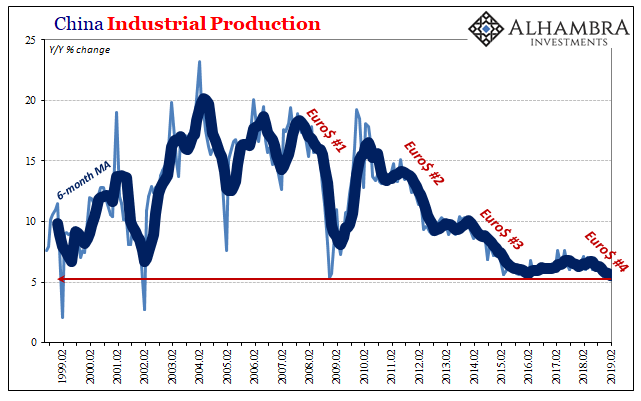

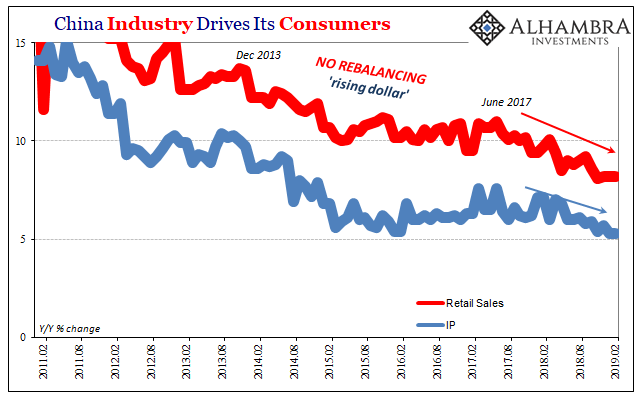

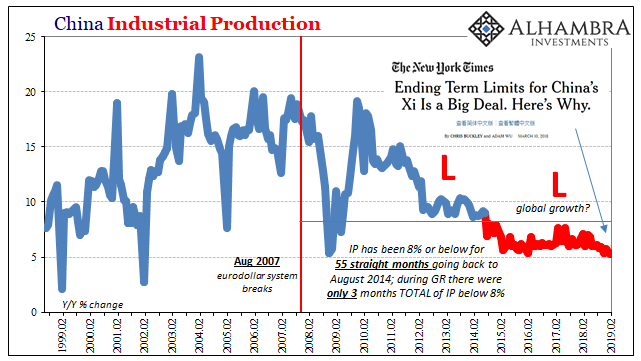

An even better illustration is perhaps the plight of China’s vast industrial economy. The very heart of the Chinese economic “miracle”, it is now the primary source of its further undoing. The rhythm of decay is, in light of eurodollar acknowledgement, unmistakable.

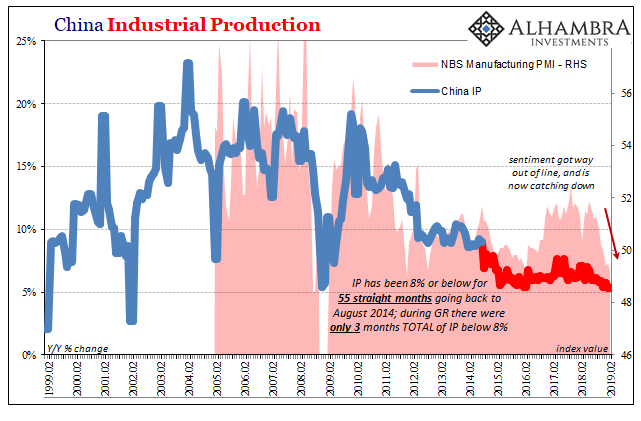

China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reports today that Industrial Production during the January-February 2019 period (the NBS combines January and February each year to minimize data skews originating from the variable placement of the New Year Golden Week on the calendar) was a mere 5.3% more than it was during January-February 2018. This was the lowest rate of growth in seventeen years, going back to January-February 2002.

As usual, there are mainstream cries about the holiday, statistical artifacts artificially suppressing what might not be so bad. I don’t believe that’s the case, but fine. The 6-month average for Chinese IP is now 5.57%. That’s the lowest – on record.

It beats (the wrong way) January-February 2016 by a tick. Only, three years earlier China was reaching the end of its unfortunate participation in the what became an immensely serious worldwide downturn registering hardest upon Asia. This one seems to be just getting started.

That’s another mainstream talking point of late; Chinese authorities to the rescue! The PBOC is doing things, who knows what, but there are a lot of things. It must be a positive, accommodative addition to get their economy restarted again.

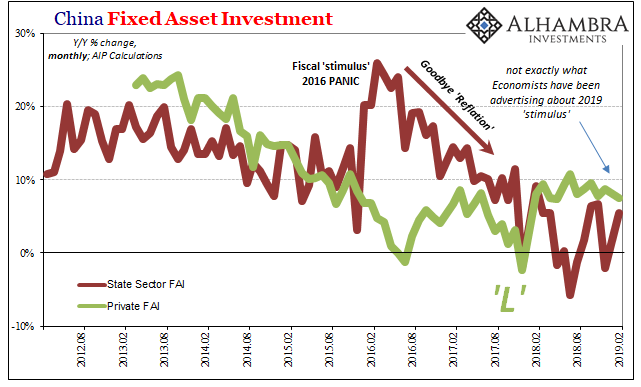

And on the fiscal side, there were hints and rumors about more than just proposed tax cuts. In early 2016, straight away, the Communist government panicked itself into a massive spending program. Clearly frightened by the prospects for worse after suffering through 2015, State-owned businesses were directed to splurge. They did.

There is no such panic indicated in the fiscal channel in 2019 – even though, by any objective measure, China’s economy seems to be facing at least those same downside prospects as three years ago if not more negative still. Given how the Chinese government works, if a stimulus program was in the works it would’ve been unleashed in January and February. Instead, State-owned FAI was up just 5.5% from a low level a year earlier.

It just doesn’t seem like there is a whole lot of appetite for expensive, ill-conceived, and ultimately ineffective rescues. In other words, exactly what Communists authorities have been saying since the 19th Communist Party Congress held way back in October 2017.

While the Western establishment had been gripped by globally synchronized growth and its purely absurd inflation hysteria offshoot, Chinese officials saw what was coming. It wasn’t so much that they might be worried about US Treasuries and QE-style money printing, rather it appears as if they finally recognized what truly mattered was what happens when the world thinks the Fed printed money to fix the shortage but actually didn’t; at first fearing the US central bank was going to do much before realizing, too late, it didn’t do anything at all.

This slowdown didn’t start with trade wars or inflationary expectations in the US and Europe. In fact, Europe in particular, inflation actually would’ve been a welcome sign for China’s beleaguered manufacturing sector – an obvious signal for real recovery that would’ve meant, if it had been real, a boost in real growth opportunity.

Never happened, even though it was widely reported at the time.

Modern China was assumed to get rich first and then reform politically: Jiang Zemin’s Three Represents which became Hu Jintao’s “harmonious society.” Xi Jinping, who took over for Hu in 2013, was supposed to continue with these.

Maybe he wanted to, expecting that there was no way the global economy could stay so dormant forever. Perhaps, at first, he thought it only a matter of time before economic growth could resume and therefore continued political progress (though not necessarily in the fashion of full democratization). There is a chance that, despite lamenting QE, China’s authorities initially decided to give it (and the three others) a shot hoping that it would get everything going again.

By the time it became clear QE wasn’t what was advertised, conceivably it was too late to develop CNY as a replacement. They missed their chance. China had fallen into the same trap as the rest of the world. What’s left, in 2019, is to hold tight and hope #4 isn’t too bad – but prepare like it could be.

Stay In Touch