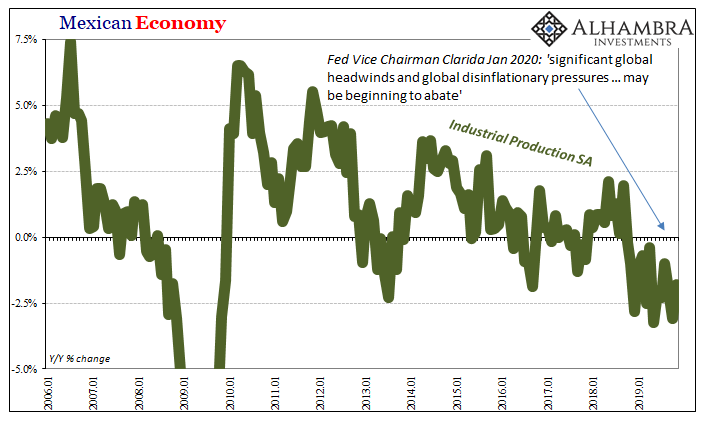

Since I advertised the release last week, here’s Mexico’s update to Industrial Production in November 2019. The level of production was estimated to have fallen by 1.8% from November 2018. It was up marginally on a seasonally-adjusted basis from its low in October.

That doesn’t sound like much, -1.8%, but apart from recent months this would’ve been the third worst result since 2009. Mexico has rarely experienced that kind of seemingly mild contraction. It signals how something has significantly changed since the middle of 2018.

Month-to-month changes aside, Mexican industry continues to paint a bleak picture of global activity. Like Germany or Japan, Mexico’s economy especially its major manufacturing base (maquiladoras) is linked directly to exports and therefore global demand.

We are interested in figuring out which way that might be heading. Vice Chairman Richard Clarida last week had said:

In 2019, sluggish growth abroad and global developments weighed on investment, exports, and manufacturing in the United States, although there are some indications that headwinds to global growth may be beginning to abate.

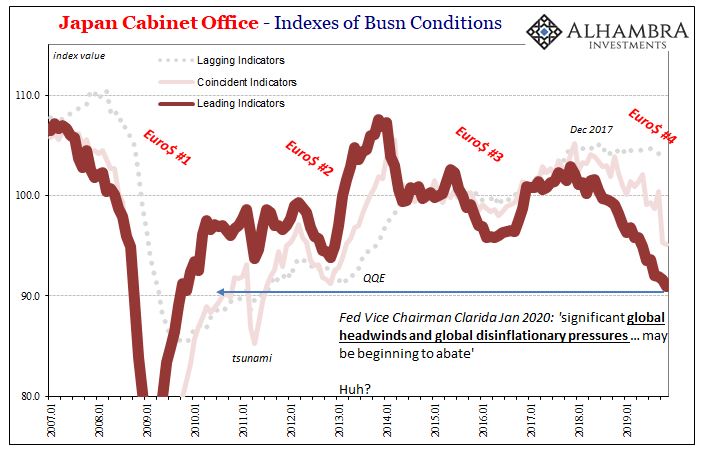

He called them “global headwinds and global disinflationary pressures” thereby unwittingly discovering the effects of the global eurodollar system without appreciating anything about their real cause. Thus, we have to ask, how would he know if they are abating since he doesn’t know what they are?

Mexico’s industrial sector helps us answer that question. Unsurprisingly, it doesn’t look like headwinds and monetary pressures are tailing off. If anything, they remain at best consistent (downturn), at worst consistent in which direction the global economy seems to be taking (downturn getting worse).

Even Fed officials have figured out (it only took them twelve years) that the US economy is no island. If there are global headwinds and disinflationary pressures those will have an effect on how the US economy is able to perform. As Clarida admitted, domestic investment, exports, and manufacturing are directly at risk.

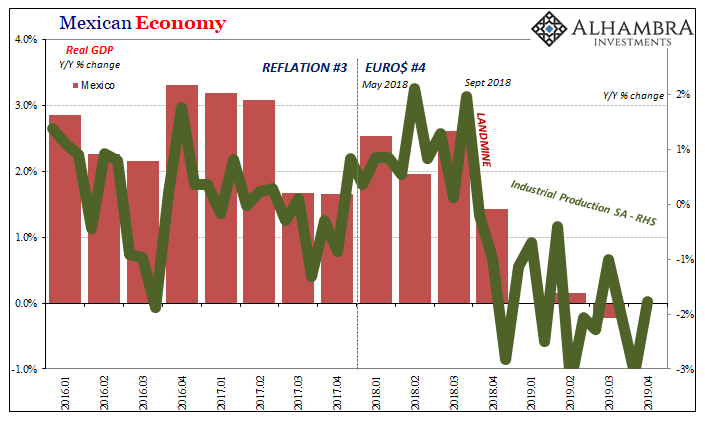

But it’s not limited to just the small corner for manufacturing, as officials would like for you to believe. The entire economy is at risk, only beginning with industry. Again, look to our southern neighbors.

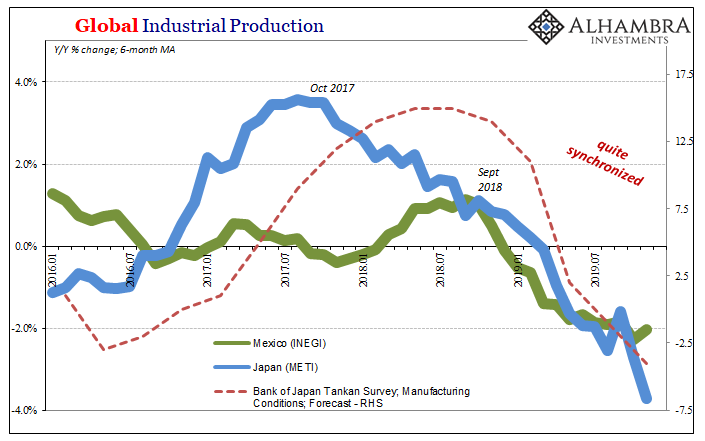

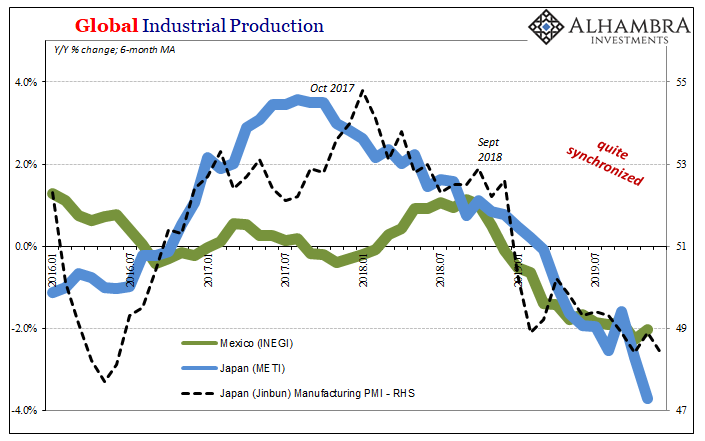

There isn’t a deep roster of sentiment indicators for Mexican industry and manufacturing like there is elsewhere in other similar economies. Take Japan, for example.

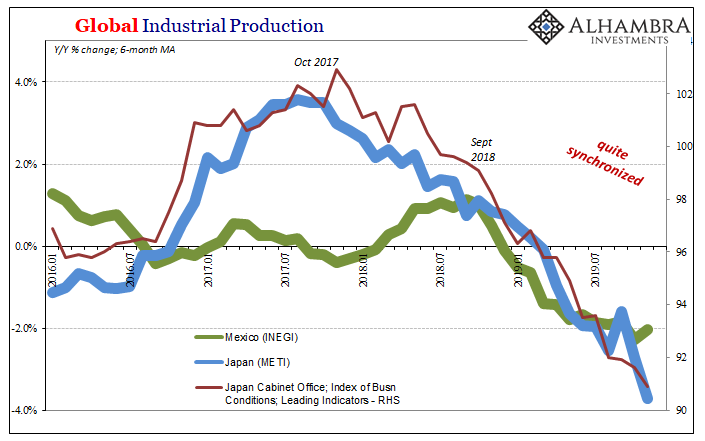

Using Japan as a similar proxy, to begin with Japanese industry has become very much in sync with Mexico.

In fact, what we continue to find is that for Euro$ #4, particularly after the global monetary landmine was struck late in 2018, the global economy is arguably the most synchronized it has been since 2009. That is likely why in many of these places we are finding conditions more like that year than any other in between.

The global headwinds seem at their strongest, more so than during the EM wipeout of Euro$ #3 2014-16.

Now the forward-looking measures in Japan continue to progress downward. Outside of a few European sentiment numbers, those susceptible to emotional love for the ECB, I really don’t know what Clarida might be looking at. Japanese trends aren’t outliers at all; there is more around the world which is and has been consistent with them than not.

If our chief aim is to analyze the state of global headwinds and disinflationary pressures, the evidence for them accelerating is abundant. Across any range of leading indicators and sentiment in Japan, for example, the trend is not just negative but getting really serious. As bad as things stood to close out 2019, what the various other indications suggest about 2020 is, again, way, way too much of 2009.

That would mean not just serious headwinds and disinflationary pressures in and around Japan. This globally synchronized downturn becomes more synchronized and therefore more (deeper) the downturn.

Germany like Japan and Mexico managed to stay out of “official” recession last year. The data here for the latter two, like most of the data for the former, says that it isn’t likely any of them will manage to repeat the feat in 2020. As bad as conditions became, they keep trending lower even though it has taken more than a year, and in some cases, more than two years, just to get this far.

Japan’s leaning worse. Mexico is heading lower. Germany at best isn’t moving off its bottom. What is Clarida seeing? I continue to go back to a (purposeful) misreading of the bond market.

This has become conventional wisdom since early September. Mistaking bond market signals, as if the 2s10s curve inversion was the only one, and a definitive all-or-nothing about recession, sentiment has shifted based largely on that mistaken impression of interest rate behavior and so has the official view of it.

Quite simply, these policymakers took only one thing from the fall in interest rates during the last two months of 2018 and the first eight months of 2019; according to their view of yields, bonds were saying recession was imminent. The backup in rates which began in September, therefore, to those like Clarida or Jay Powell it was the bond market backing off from what they felt was a recession declaration.

Nope. What the plunge in yields from the landmine forward had meant was economic risks were rising, reaching substantial proportions by August last year. Nothing about recession specifically, only that the risks of one (globally) had exploded from the lackluster not-booming economy of 2018.

The relatively slight rise in yields (why isn’t the UST 10s past 2.25% on its way to more than that given trade deals, stocks, and Clarida’s view of abating headwinds?) was the bond market reassessing the risks in an always fluid situation. This isn’t abnormal; it’s how it always happens.

The bond market, like the data, is saying that conditions and trends haven’t really changed – which is entirely the problem. There’s nothing substantial which indicates things are turning around and therefore the risks of an even worse downturn continue to be.

The market is giving the Fed, ECB, and even BoJ (perhaps Banxico, too) the chance to prove their view. But at some point this turnaround they’re talking about has to actually turn around; data as well as the vast majority of sentiment and leading indicators from around the world. Those, as we see in Mexico as well as Japan, bellwethers for global demand and therefore the effects of headwinds and disinflationary pressures, are not.

Stay In Touch