China’s yuan just isn’t a stable currency. I don’t mean its exchange value, either. CNY floats up and down on the whims of the eurodollar. The PBOC can and does limit the daily trading band, but often at tremendous cost (ticking clock). Therefore, the internal constraint governing this dynamic is a symptom of a world that isn’t going to accept yuan as an alternate reserve.

There are any number of ways to see this in real-time, two above all others.

First, the Dim Sum market. China’s overall bond market is estimated to be around $11 trillion onshore. To become a real, usable global reserve there has to be a robust mechanism for depth and liquidity offshore (I didn’t make the rules). Financial and economic agents must be able to access monetary resources in ready, efficient fashion. A global reserve, as Robert Solomon pointed out long ago, must meet all three of his criteria:

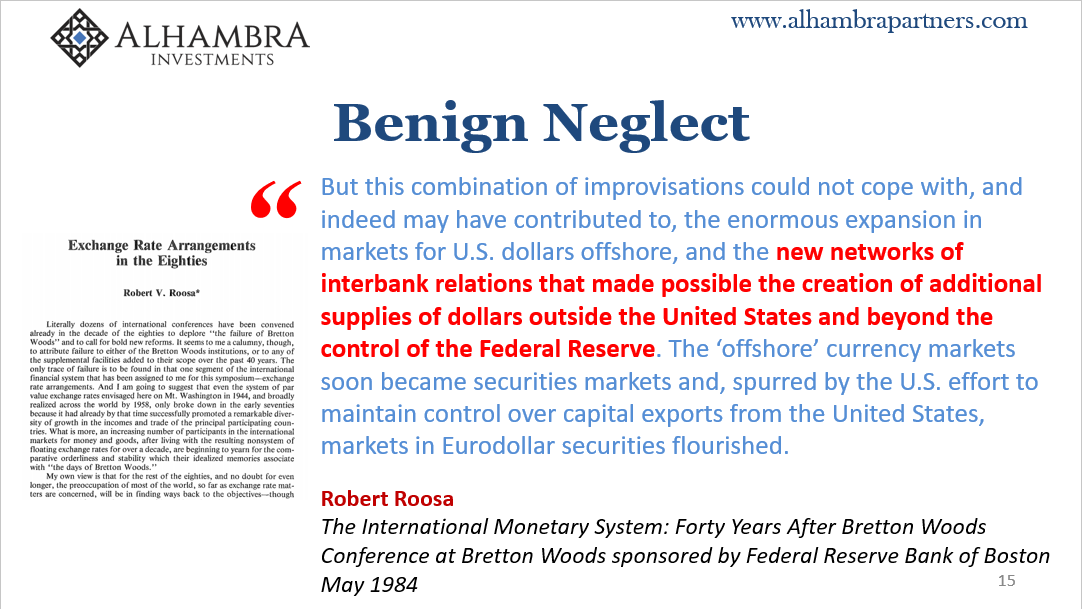

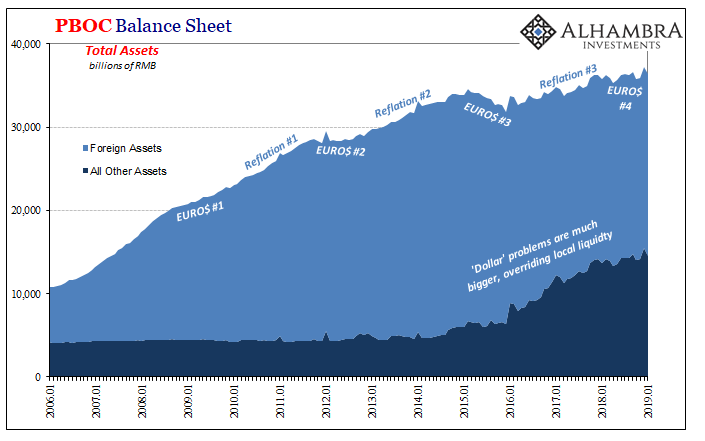

Long before Bretton Woods was closed down, the eurodollar had fulfilled all three in a novel and very modern sort of way. It was money without borders, a freedom that allowed participants to easily use what was globally available to meet the monetary demands of a globalizing world. The breadth of the system given these parameters is indescribable.

China’s monetary system does not fit these requirements. It doesn’t come close.

Many years ago, before Euro$ #3, spotting opportunity Chinese officials tried anyway. When it looked like the Great “Recession” would hobble the developed world but not Asia, they took a first step encouraging offshore currency in Hong Kong (CNH) followed by offshore bonds. These are called Dim Sum, issued by whatever global corporate (hopefully more banks than not) denominated in RMB.

We often hear about how a reserve currency must have depth, this is one element to it. There has to be liquidity in it, sure, but what does that really mean? Hardly anyone seeks to understand the answer. It’s about plumbing and more, an intense, complex, and, above all, layered infrastructure. Multi-dimensional.

People talking about petroyuan, especially the introduction last year of an oil futures market denominated in RMB, are missing the point. Oil is an important commodity, no question, but unless, until the Dim Sums start seeing any realistic scale it is moot in the context of a functionable reserve alternative. Issuance here peaked, unsurprisingly, in 2014 at a fraction of Eurobonds.

Instead, it continues the other way. Rather than the world’s corporates seeking out RMB to ditch the dollar, China’s corporates keep begging in the eurodollar space. They have no choice, as even the Chinese federal government has shown in each of the past two years; authorities have issued a benchmark Eurobond, denominated in dollars, in order to aid China’s corporate sector in better pricing for what dollars they continue to require.

Dim Sums (and even Pandas, RMB onshore bonds) aren’t getting it done and the CNH experiment failed, too. Bilateral swap arrangements are nice when you can get them, even a petroyuan contract, they just don’t add up to the necessary infrastructure that are universally recognized to satisfy all of Robert Solomon’s conditions.

In fact, what we see in yuan today continues to prove how it doesn’t register near enough in any of the three. Despite eleven years of intermittent and costly malfunction, the dollar remains a one-way street. It is still the eurodollar’s world; we are all just trying to live here.

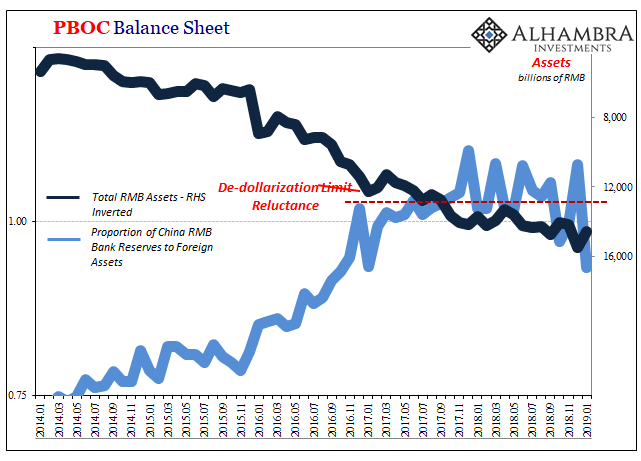

Who knows this most of all? The People’s Bank of China. The central bank’s action maybe even more than the retrenching state of the Dim Sum market tells us that RMB is not ready for primetime. Having been talking about it since Zhou Xiaochuan in March 2009, if they could have they would have by now. Monetary authorities won’t even let it loose internally.

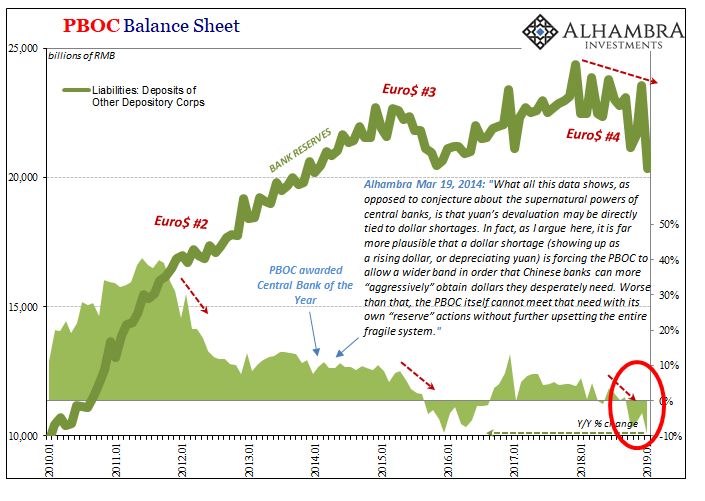

The lone exception was 2016 and 2017. For two years, China’s central bank actively sought to use its theoretically unlimited printing press to fill in the huge hole on its balance sheet (asset side) created by eurodollar flight. Basic central bank accounting, if assets decline for any reason (in this case, using foreign reserves to supply “dollars” to China’s corporate sector by “selling UST’s”) the liability or money side must as well.

Unless, you actively offset the decline in foreign assets by an equivalent or greater rise in domestic ones.

For nearly two years, the PBOC pushed through a rapid RMB window expansion. It did not, however, result in a monetary explosion of similar proportions; again, this was only meant to offset what was still being lost in terms of forex. The net product was minor monetary growth at best lackluster during 2017.

For what? It’s not as if China’s economy magically restarted, taking off on a path to reclaim lost economic glory. Rather, the costs of modest reflation must have been alarming. CNY fell sharply throughout 2016 and only turned around in 2017 due to magic tricks (Hong Kong). We don’t yet know the full accounting for this bypass.

The PBOC sees limited gains and therefore is not willing to risk any more naked RMB printing. They are making a very conscious effort to avoid de-dollarizing RMB more than it already has. That tells us China’s monetary authorities are worried about Solomon’s pillars, particularly #3 CONFIDENCE (and also #1 ADJUSTMENT).

So worried, they are willing to go back to internal monetary contraction so as to avoid upsetting any further.

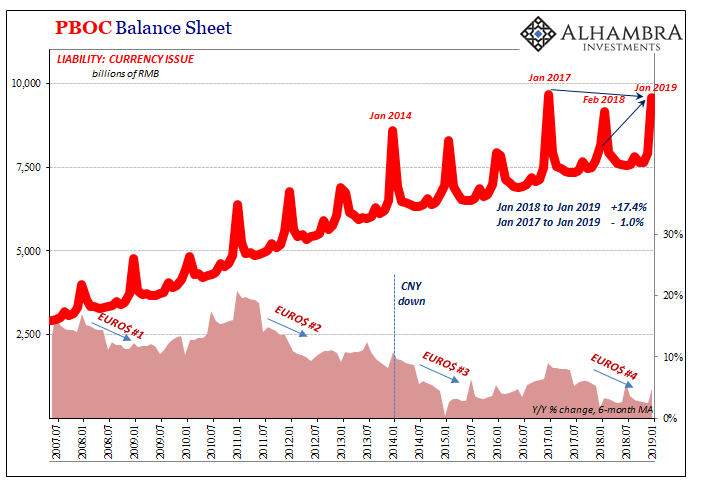

The numbers are skewed for January 2019 because of the usual Golden Week disruptions. For this year, the monetary peak in currency occurs in January compared to February last year. Thus, year-over-year currency issue was up 17% but on an apples to oranges basis. The last comparable January was 2017, and currency outstanding last month was 1% less than it was two January’s ago.

But here’s the thing; to even manage -1% this required a 9.4% contraction in bank reserves. There are Golden Week 2018 to 2019 skews here, too, but overall official liquidity is being sucked out of the banking system in order to accommodate the smallest (average) currency growth on record.

The reason is simple. The asset side contracted in January with that decline attributable to large reductions in PBOC RMB offerings. Foreign reserves were just slightly higher. Given China’s deteriorating economic situation, this quite obviously appears to be a conscious choice (including RRR cuts).

Chinese monetary authorities are telling us that not even they believe RMB is ready for anything like a reserve currency role. If it was, they would start to break out of these eurodollar-imposed constraints and print RMB as necessary. A lot of RMB printing would be necessary. The very fact that they did (2016-17) and now don’t (2018-) demonstrates how China’s central bankers have come to believe domestic money constraint (sharply declining bank reserves and slow to no growth in currency) is the lesser of the two evils.

They might be wrong about that, of course. Still, if yuan was poised to take over a more central role in global money you would definitely expect those closest to it to be a hell of a lot more confident about it than this. If euroyuan was anywhere close to rollout, nobody would have to care so much about China’s forex least of all its central bankers. The PBOC sees CNY as so fragile they’d rather risk internal monetary contraction and the growing economic costs associated with it.

China’s yuan just isn’t a stable currency. I don’t mean its exchange value.

Stay In Touch