Whereas China is embroiled in pig wars, its neighbor India is waging one against onions. African swine fever has decimated the former’s stock of hogs, leading to rapidly rising food prices at maybe the worst possible time. On the Indian subcontinent, same result as far as prices only in this case late monsoons have swamped the onion harvest.

The shortage has been so bad it led the Modi government to halt exports of the vegetable in order to keep enough supply in-country; therefore, prices down. It hasn’t really worked, at least not yet.

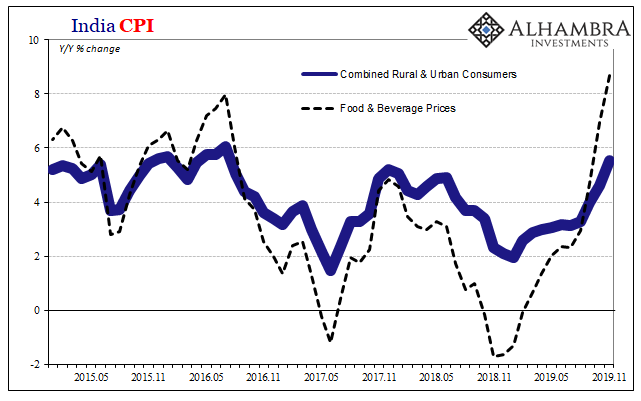

According to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the nation’s central bank, inflation has jumped over recent months due almost entirely to onions. The overall CPI index gained 5.54% year-over-year in November 2019, accelerating from 4.62% in October and 3.99% in September. Food prices spiked more than 10% last month (an 8.66% increase including the prices of beverages) as the onion shortage takes its toll.

Already several other countries are attempting to take advantage of India’s export ban. Indian farmers supply, by far, the most onions across Southeast Asia. As a staple of most diets in the region, this one vegetable can cause a lot of chaos. It has meant both pain and opportunity: pain as onion prices rise inside and outside of India; and opportunity as farmers in other countries not affected by the monsoon can cash in.

The government in Bangladesh, for example, has authorized subsidies for onions traded through its state-owned Trading Corporation of Bangladesh. That company will be scouring the world for replacement supplies, from places like Turkey and Iran, Egypt and China.

That’s how markets work; a supply imbalance causes prices to adjust which signal profit potential for someone with additional capacity and/or supply. Ceteris paribus.

There’s always a catch.

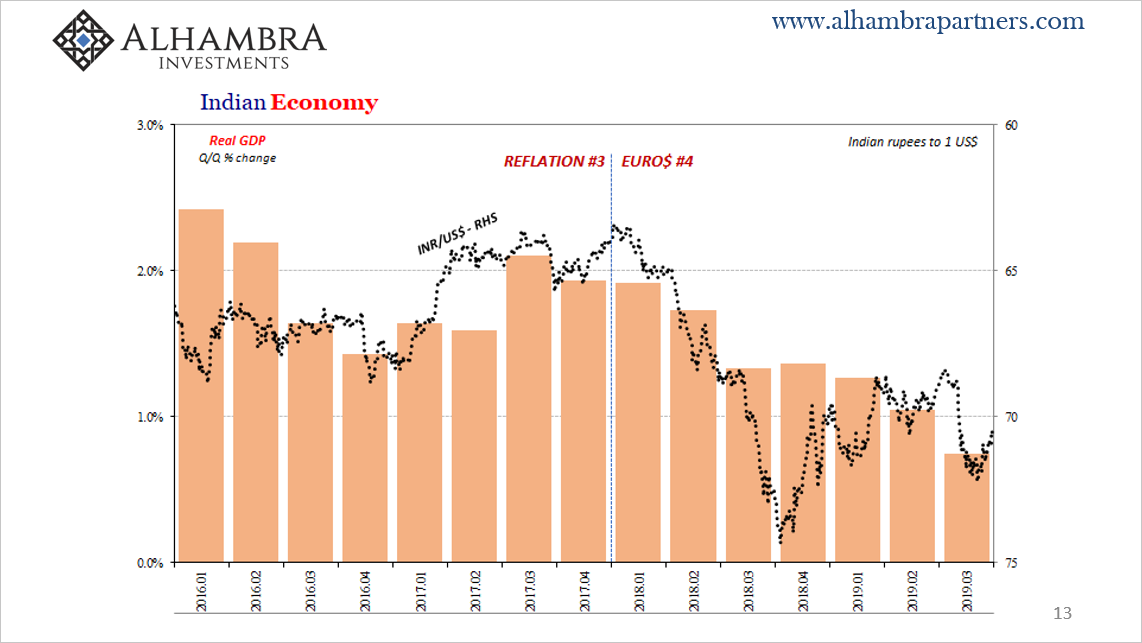

For India’s economy overall, it appears more and more to be caught in one. As I said before, this bout of food price inflation cannot have come at a worse time. It has now caught the central bank unprepared, unsure of what to do next. The economic situation already dicey, the RBI having reduced rates throughout 2019 to this point.

It was widely expected to do so again at its policy meeting earlier this month.

But with the CPI now well above its 4% target range, central bank officials (risking Prime Minister Modi’s wrath) refrained from that next rate cut for fear it might contribute to the inflationary situation already getting out of hand.

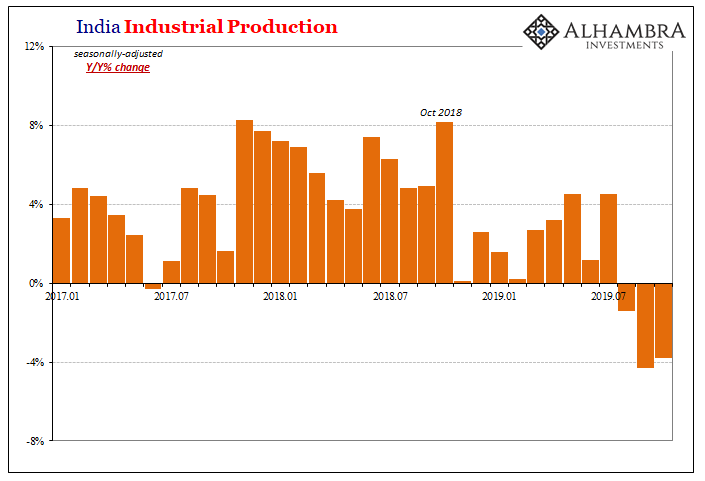

It could not have been an easy call for the RBI. A little over a week after making their policy choice to do nothing, the central bank released those November inflation figures at the same time India’s Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation reported yet another contraction for Industrial Production.

For an economy predicated so much on industry functioning well, a third consecutive minus for a series that only rarely falls below zero was beyond mere unwelcome news. The RBI truly stuck between the inflationary rock and this industrial hard place with no clear direction to follow.

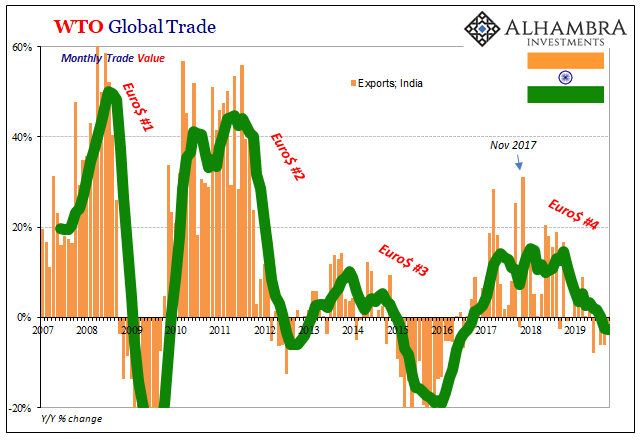

But it wasn’t supposed to be this way, not according to “trade wars.” India perhaps more than anywhere else in the world should be utterly booming. With the US quite serious about imposing trade restrictions upon China, then the Chinese’ loss should have been someone else’s gain.

That’s how markets work. All things equal, ceteris paribus, increased costs to Chinese products heading for US destinations should’ve signaled other producers to enter the game and benefit from the local fallout. Why not India?

Tariffs on Chinese imports into the US mean that India is in an almost perfect position from which to benefit off the redistribution effects of American protectionism. Not only that, the currency has depreciated more than 10% since the beginning of 2018, which in addition to China’s pain should have turbocharged its export sector that much more (according to the mainstream view).

Instead, the opposite has happened.

If the world’s economic problem in 2019 has been “trade wars”, causing this “unexpected” detour away from globally synchronized growth, as everyone keeps saying, where are the winners? Protectionism, as my colleague Joe Calhoun loves to point out, doesn’t depress trade it redistributes the activities, terms, and benefits. For every good not produced in China there will be the same thing or equivalent produced somewhere else.

Ceteris paribus.

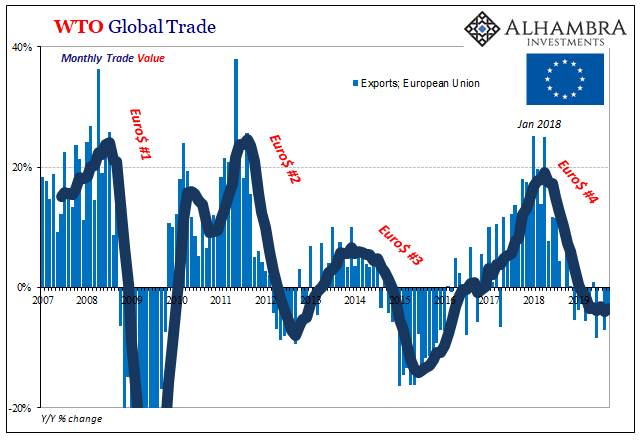

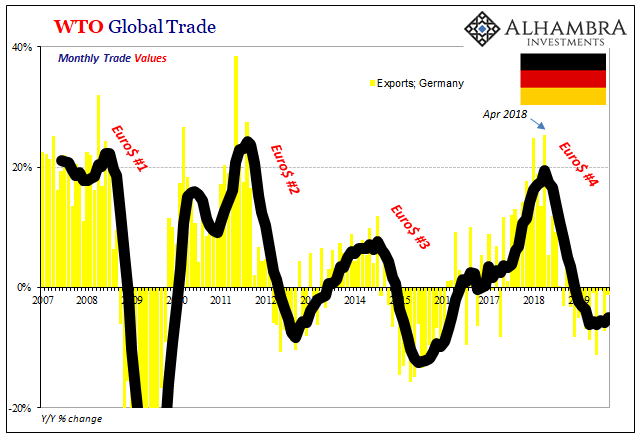

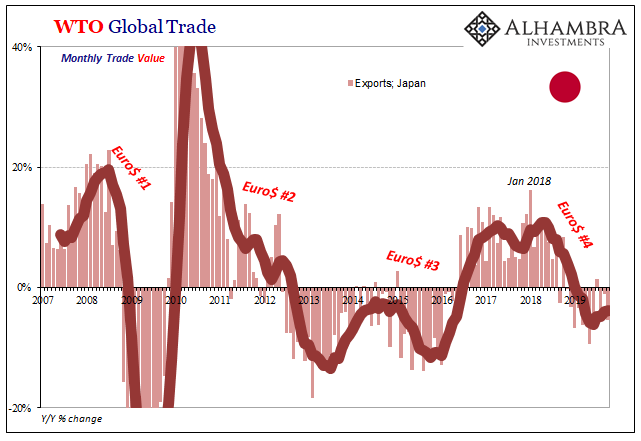

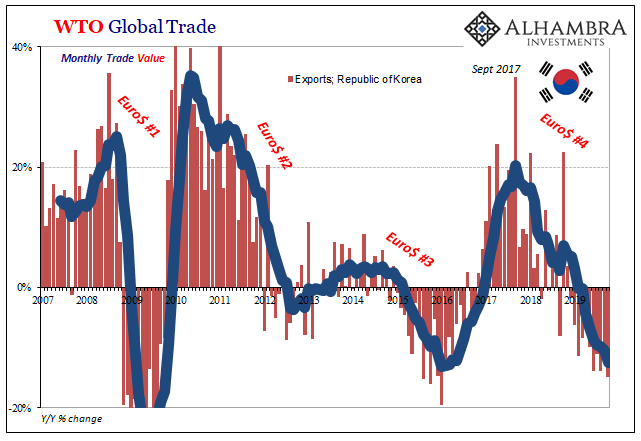

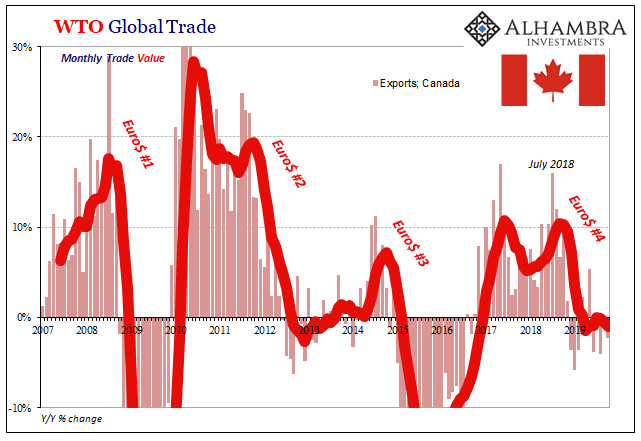

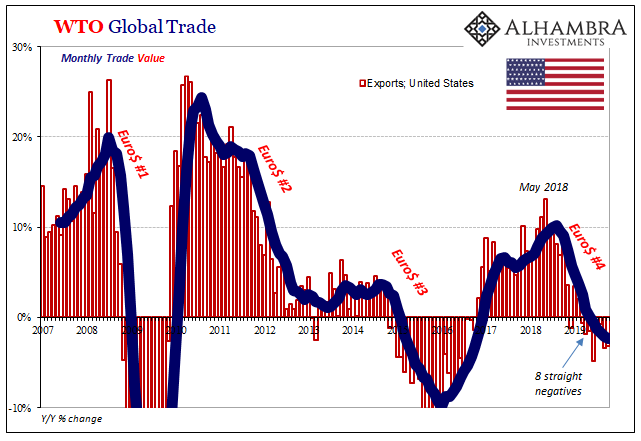

But that’s not what we find. Instead, there are no winners anywhere. See if you can find one from among every major export economy:

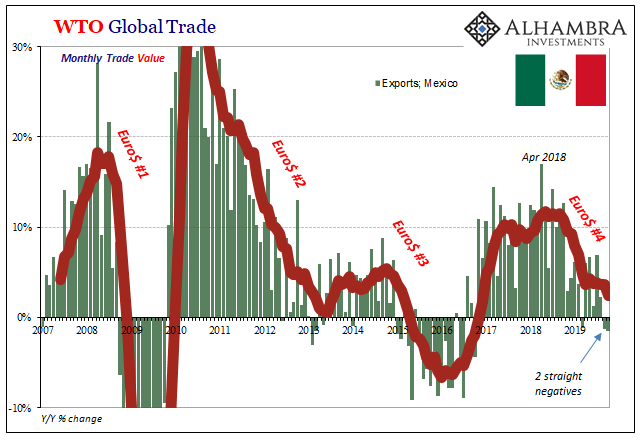

Even Mexico, which by all accounts should be very well-positioned to pick up slack from China, that country has seen its export growth disappear. And now minus signs south of the (US) border, too.

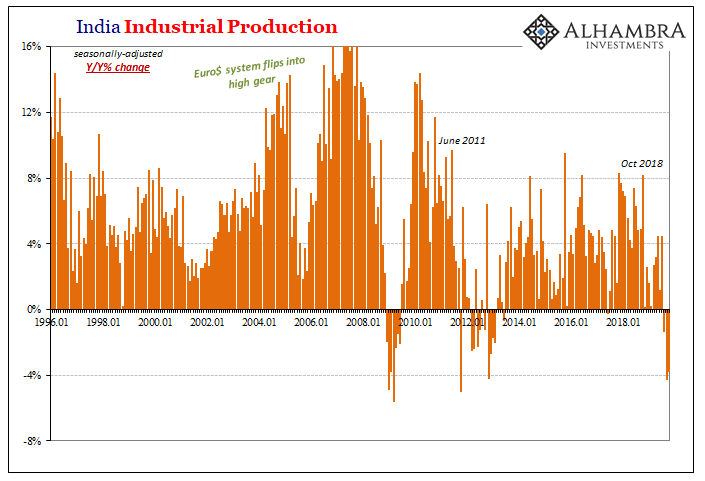

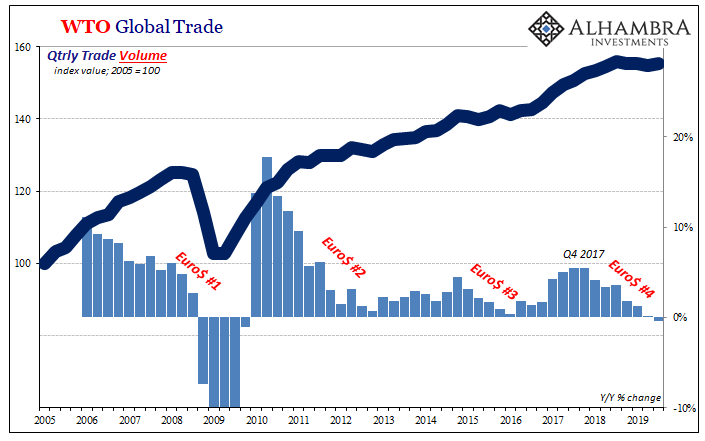

Trade wars redistribute trade, but what we find here is instead a reduction in trade all over the world severely impacting the global industrial economy. One that remains at best ongoing and at worst accelerating. Look at all the charts above – they are basically the same one, the same patterns repeated over and over (and over and over).

Not only is trade falling now in all these places, it did the same things four years ago, four years before that, and four years before that. A few billion in US tariffs on Chinese goods didn’t cause any of it.

The WTO says that total trade volume (meaning the number of physical units, as separate from trade values which are shown on all the charts above and take account of currency and price translations) across the world was less in Q3 2019 than it was in Q3 2018. It was the first time since 2009 that total trade volume had declined on a year-over-year basis, and it’s not reversing.

This is why FedEx Chairman and CEO Fred Smith shocked everyone with his comments today (h/t Zerohedge). People in America, especially stockholders, don’t seem to realize what’s going on out there in the rest of the world. As a freight carrier, he doesn’t have the luxury of listening to Jay Powell about non-specific “cross currents” and repo interventions that don’t actually intervene in repo.

I might also say that I think in this country, there is a little bit of misunderstanding — estimation of what’s going on in the rest of the world, the e-commerce growth, the technology sector that we had, the tax cut, all of these things have led us to have a high increasing employment. It’s led us to have reasonable GDP growth. That’s virtually not true any place else in the world.

So, it’s really a tale of two economies and the stock market, of course, is very bullish, but the industrial economy does not reflect any growth at all, worldwide, to speak [of].

People are pleased that “trade deals” are beginning to replace “trade wars” in a lot of ways, and they should be. They are also encouraged by a near-uniform global rate cut cycle, some featuring relaunched QE’s, a purported avalanche of monetary “stimulus.” The trend in terms of sentiment has turned solidly optimistic since early September.

And it is predicated upon false assumptions. The problem has been, and remains, the eurodollar system. That’s the only thing which can explain all the evidence you see above. Not trade wars. It is the factor which comes first and foremost, having destroyed ceteris paribus and in doing so wreaking havoc in places like India at the same time it erasing any ideas about local monetary “stimulus.”

I’ve written all along how everyone will be shocked when the trade deals get done and the world still ends up with more Fred Smith-like commentary anyway.

Stay In Touch