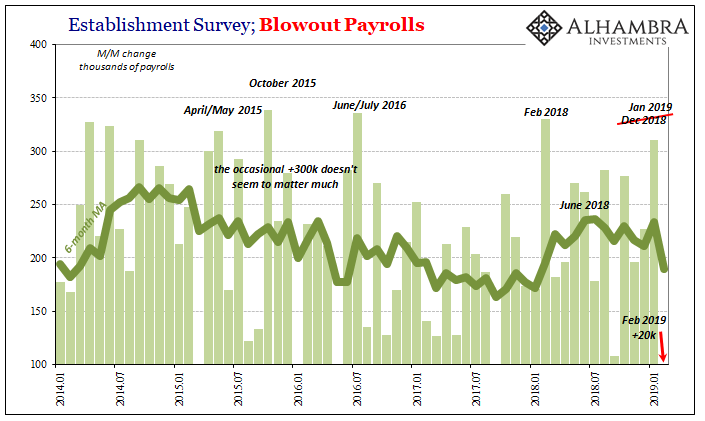

The BLS giveth, and the BLS taketh away. That’s not really what has happened, of course, but for many it can seem that way. February’s payroll report obviously stands in striking contrast to January’s. The latter was a blowout, over +311k (revised), hyped near and far as proof of decoupling, the US economy the only clean shirt. In comes the latest number, equally a blowout if in the opposite direction, +20k, poof goes the narrative.

Sure, there was snow and lingering shutdowns and all sorts of factors – just like there are in each and every month. The real truth of the matter is the payroll reports are noisy. Just look at the confidence intervals (at only 90%) for the monthly change. What the BLS actually says with its headline, +20k in February 2019, is that if they resample the data from the beginning 100 times, in 90 of them they would expect the net change to be somewhere between -95k and +135k.

You should never take a single month’s number too seriously. With that in mind, you should always expect the good blowout months to receive undue attention and be made to inappropriately extrapolate a booming economy.

What we care about is the average across several months.

More and more we are starting to see the outlines of some softening in the labor market. We can’t really know by how much because of both the noisiness of the data (even spread out across something like a rolling 6-month interval) as well as what revisions might due to the estimates if things really are turning out badly.

Even if we leave out February’s number, or account for it being revised higher over the next few months (which is as likely as not), the average headline change has stalled and best case has very gently reversed. The second half of 2018 for the Establishment Survey is very reminiscent of the second half of 2014. Big surprise.

As of the latest benchmarks, it was March 2015 which introduced Euro$ #3 as a possibility in the payroll data. You can see it plainly on the chart above, though I hadn’t marked it, the month which moved the average lower and started to indicate the slowing of employment growth which would last several years. It was the ultimate product of a very near recession stain on the very dirty US economic shirt.

The pattern being repeated, February 2019 showing up as it has, there is an increased probability of something similar. That’s about all the payroll reports say right now. As more of a lagging indication anyway, it is corroboration as to how the US economy may have peaked last year and is behaving today in a more uncertain fashion.

It doesn’t have quite the headline pop as January’s big blowout, nor anyone looking for play on February’s big downside.

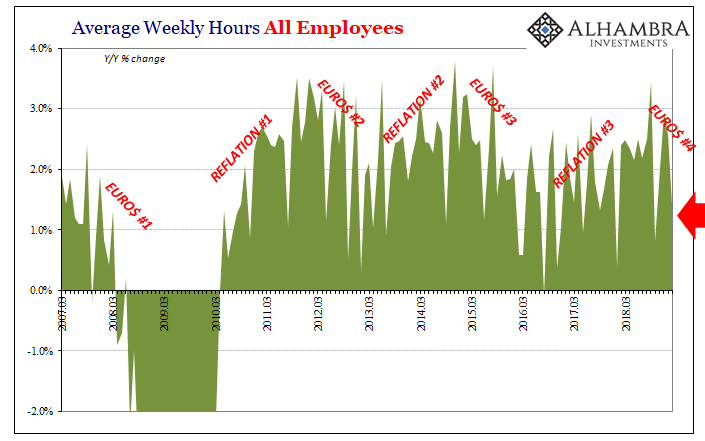

There are several other indications beneath which support this less certain state. Average weekly hours worked, for example, gained just 1.4% year-over-year in February. The 6-month average is back to 2.2%, down from a peak of 2.5% around September 2018. The increase in average hours would top out in the last downturn at 2.9%, again around March 2015.

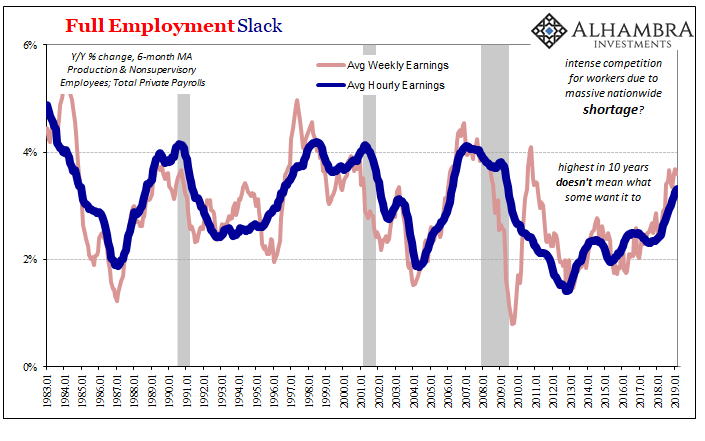

In terms of wage growth, average hourly earnings rose 3.48% year-over-year last month. That was slightly better than January’s 3.31% (revised) but still less than December’s 3.50%, the widely celebrated highest in a decade. There is nothing wrong with rising wages, but interpreting this data to mean a huge shortage is a mistake. I’ll have more to say about this with the BLS updates to Unit Labor Costs and related compensation figures.

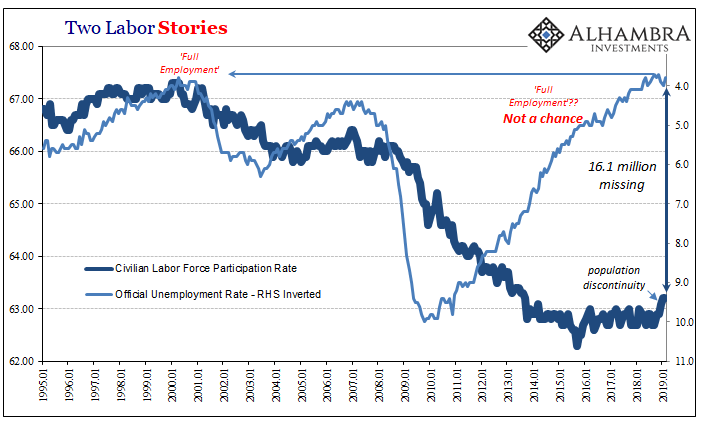

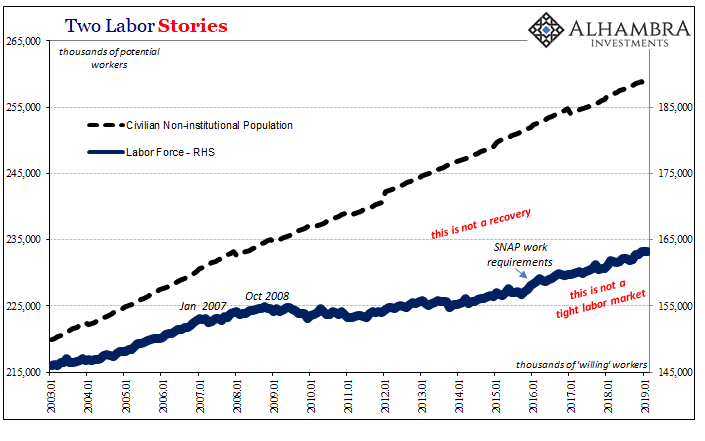

The overall economic narrative last year was a booming US economy running up against a historically tight labor market. The highest wage gains in 10-years and plus +300k (as December was initially figured, at least under old benchmarks) seemed the perfect evidence for the claim. Set aside the shock value of February’s headline number, what’s left instead is a much less clear, far more ambiguous labor market with still no sign of it being tight let alone uncharacteristically so.

These might be the signs of an economy hitting a soft patch which isn’t all that unusual, or wasn’t before 2008. Or it could be a sign, like 2014-15, of a more complete transition out of reflation into downturn. If the latter, there is no way to tell by the labor market data alone what that would mean. Though they are often made out to be, especially whenever a good month shows up, or what passes for one nowadays, the payroll reports really aren’t that authoritative.

Stay In Touch